Who's hysterical?

Sir, I have just read Matters of Moment (Motor Sport, March 1987). Is it not yourself who is getting hysterical, by taking all John Lyon says too literally? I have been…

For contextual reasons, a little background is perhaps required before we examine the latest book from one of America’s foremost motor racing analysts, and occasional Motor Sport contributor John Oreovicz.

I must admit to having almost zero interest in politics. In the UK, this is partly because Westminster seems to have become a toxic playground for the terminally incapable – but even before then I found it hard to get excited about some of those involved. And it’s the same when power struggles break out in the parochial business of motor racing. At the heart of the FISA/FOCA conflict in the early 1980s, I’d read a couple of paragraphs in the specialist weeklies to see who was patronising whom, and why, then despair: “Please stop bickering; just get on with the bloody racing…”

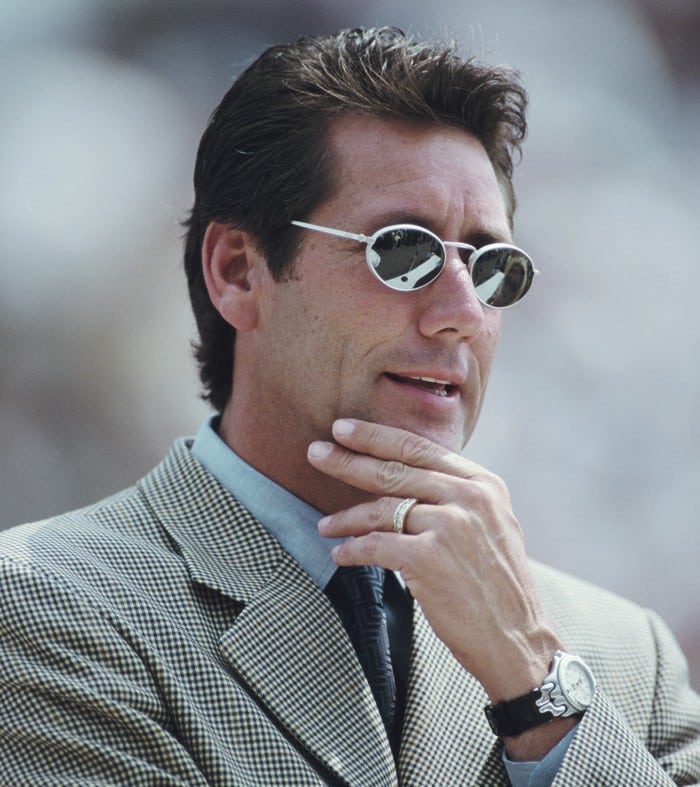

Tony George, founder of the Indy Racing League and a chief protagonist in the split

In which light, a 432-page book about schisms within the American single-seater mainstream should have been reviewed by almost anybody else. And yet…

It helps that Oreovicz is a very fine writer, of course, but this is by no means as dry as its central motif might suggest.

It is 25 years since CART (Championship Auto Racing Teams) and the newly formed Indy Racing League went head to head and carved American single-seater racing in two. That peaked on May 26, 1996, when CART ran its US 500 at Michigan on the same day that the IRL staged its annual 500-mile showpiece at Indianapolis. CART appeared to hold most of the aces – Penske and Newman/Haas foremost among the teams, Paul Tracy, Al Unser Jr, Michael Andretti, Bobby Rahal and a couple of Fittipaldis within the cast of drivers. Indy had a few ex-F1 veterans, not least Michele Alboreto and Eddie Cheever, but those such as Racin Gardner, Tyce Carlson and Billy Boat weren’t ever likely to become household names. Viewed from afar – specifically on cable TV at a brasserie in Pau, where a section of the European racing community had gathered for the annual street race – it appeared to be a masterclass in self-destruction.

It would be a few years before any CART team bought the required kit (the series ran to different regulations) to return to Indy. Ganassi broke the mould in 2000, winning the race with Juan Pablo Montoya, and a trickle eventually became a stampede. Oreovicz: “Montoya, who had never been around the Brickyard in a racing car, raised a few eyebrows with his apparent indifference toward the historic venue after hitting 217mph on his fourth flying lap during an April test. ‘When I thought of racing in the United States, I thought of CART – not the Indianapolis 500,’ he commented. ‘So far, it’s been very simple to get around here’…”

Very Montoya, that…

It would be 2008, however, before the CART series was finally extinguished and American single-seater racing had a reunited focal point, by which stage NASCAR had moved well ahead in the ratings.

But this is not simply a book about that split and its consequences. It covers pretty much the whole history of Indycar racing, not in terms of detailed race reports but with a stroll through the events, plots and subplots that have shaped it.

The background detail fluctuates between the dramatic –a fatal gunfight involving IMS official and former racer Elmer George, his estranged wife and her new boyfriend, for instance – to the mildly comical. In 1979, when CART was formed and American single-seater racing had previously divided itself in two (albeit relatively briefly), teams committed to the new series had to use pick-ups to tow their cars the final few miles to a pre-season test at Phoenix, because floods had washed away most of the main road and regular transporters couldn’t get through.

“This is by no means as dry as its central motif might suggest”

There’s a bit about why promising young racer Jeff Gordon ended up racing stock cars, despite initially harbouring Indy dreams. Linda Conti, whose team gave Gordon a Super Vee test, recalled visiting the CART paddock to discuss opportunities. “AJ Foyt was the only one that spent any amount of time talking with him, and I don’t think Carl Haas even said hello. Jeff was pretty dejected on the ride home. He thought teams might actually want to hire him because he had talent, but Foyt told him, ‘Get the hell away from these assholes and go NASCAR racing. They actually want a driver, not a cheque.’ I never heard Jeff mention the Indy 500 after that.”

There’s also a nice line about one of the reasons CART superstar Rick Mears opted to remain in America, rather than pursuing any F1 aspirations in the slipstream of a successful test with Brabham: “Knowing there was a 7-Eleven on every corner.”

This is a political story with strong human content, an erudite illustration of how sport shouldn’t be run and a cracking good read.

John Oreovicz

John Oreovicz Octane Press, $27

ISBN 9781642340563

Darren Banks

Warmly received when first published, it swiftly sold out. One of Britain’s most promising young racers of the 1970s, South lost a plum seat with the Toleman F2 team in 1980 after testing an F1 McLaren without telling his employer. He subsequently picked up a Can-Am deal, but his career ended that summer when he suffered devastating leg injuries in a practice accident at Trois-Rivières. This honest, compelling account of a career cut short has now been reprinted. SA

Performance Publishing, £25

ISBN 9780957645028

Jeremy Walton and Peter Osborne

Four-wheel-drive Capris, mud-caked Minis and a Cosworth-powered DAF: this fond look back at the early days of rallycross is nothing if not eclectic. It is proudly personal, rather than wearing ‘official history’ pretensions and all the stronger for it. Compiled from black and white photos from 1969-71 discovered in a dusty garage matched with reports from Motoring News, what the book lacks in gloss it makes up for in vim. A contents list would have been nice but this is an unashamedly agricultural romp through a period of what it calls ‘motorised madness’. JD

fromthedrivingseat.com, £9.99

Peter Moss and Richard Roberts

An impressive assemblage of Rolls-Royce advertising from the earliest text-only fliers for the 1904 10HP to romantic images for the 1939 Wraith, comparing approaches in Britain – tradition and privilege – and the US – achievement and success. Claude Johnson’s PR genius is clear, soon cementing RR as “the best”, backed by aristocratic endorsements. Extracts of company minutes show RR spent £15,000 on publicity in 1932 alone in multiple arenas (not Motor Sport!). A suitably high-quality production offering hours of browsing. GC

Dalton Watson, £95

ISBN 9781854433107