Scream Test

Honda's highly strung new sportscar, the S2000, is no ordinary machine. Matthew Franey heads to Prescott Hillclimb School to find out why. The purpose of this story is two-fold. Firstly…

Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images

Tom Walkinshaw was always one to leave a strong first impression. Love him or loathe him – and there were plenty on both sides of the divide – this was a man who had presence. What he lacked in height was more than made up by width (he must have been terrifying to face on a rugby pitch), but it was his manner that made you pay attention: quiet, composed, softly spoken, intimidating… He was a figure of significant power. And he knew how to use it too, without moving a muscle. A look could be enough, and was that humour in the glint in his eye, or something darker? Whatever, he enjoyed his power and the effect it could have, which is perhaps why he was such an effective racing driver as well as a team owner. If the latter was where he left his most significant mark on motor sport, it was the driving that came first – and it’s arguably where his soaring ambition was most forcefully expressed.

Win Percy remembers exactly where he was when he first met Tom Walkinshaw. He left an impression on that day, too. “It was at my first touring car race, in a Toyota Celica 1600 at Mallory Park in March 1975,” says Percy in that warm Dorset burr. “He was in London Sportscar Centre’s 2-litre Escort. I didn’t know anybody in touring cars then, I was a rallycross and autocross driver. Everyone was new to me. I’d diced the whole race with this Escort running in the bigger class, and he crossed the line about half a car in front. Afterwards, I was being congratulated on winning the class, and this guy shoulders his way through the crowd. He said: ‘Win’s a funny name.’ ‘Well, it’s Winston,’ I replied. He grunted as he did. ‘I understand this is your first touring car race.’ Oh dear, what have I done? Then he said: ‘One day I’ll have my own racing team and you’ll be my driver.’ We shook hands, and he walked away.

“Who the heck was that? That was the first I’d ever heard of Tom Walkinshaw.”

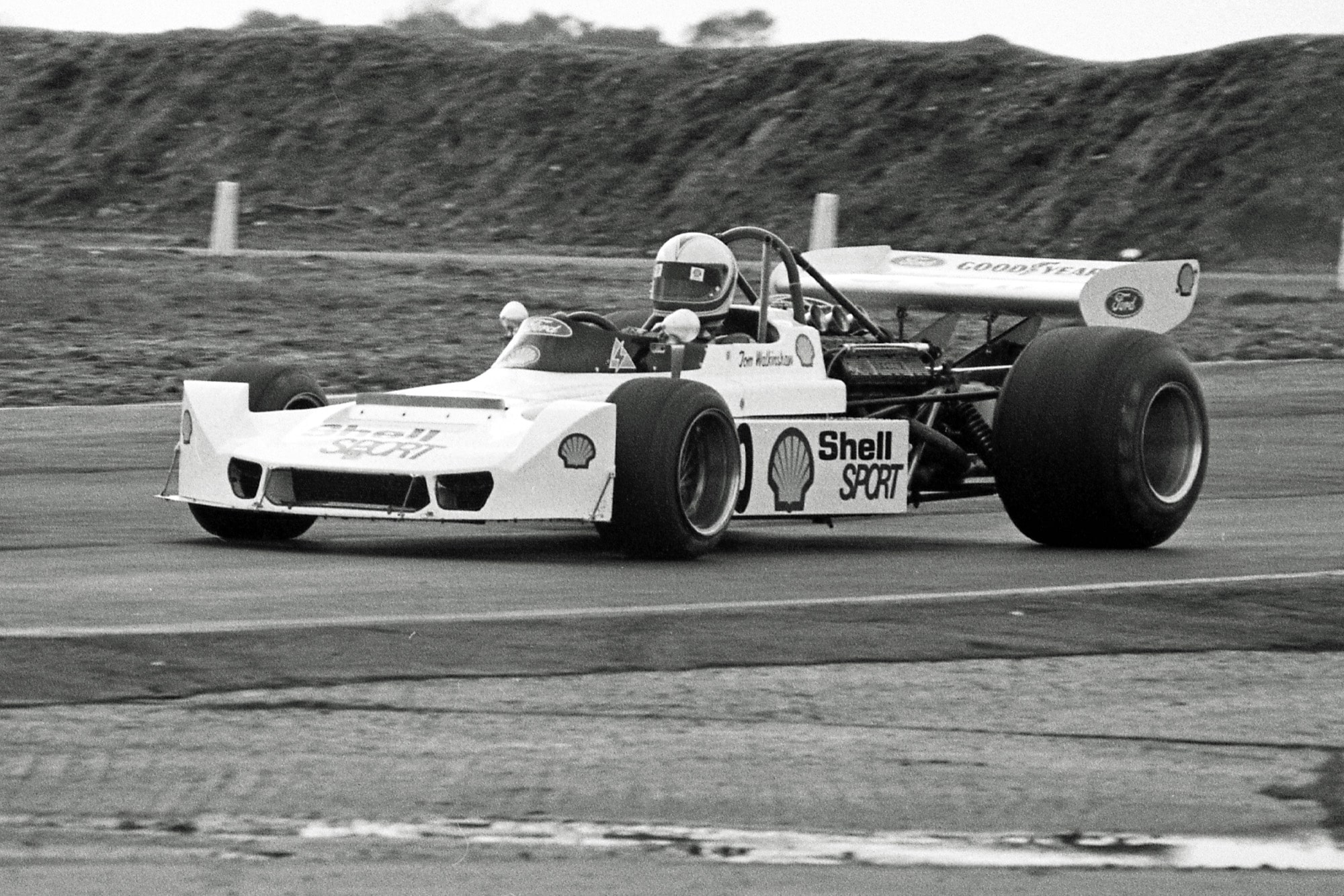

As a driver, Walkinshaw made it to F5000 on the single-seater ladder, here at Snetterton in ’74

The intention at first had presumably been Formula 1, such was the man’s ingrained ambition. Born in Midlothian in 1946, Walkinshaw was a Scottish Formula Ford champion by the end of the 1960s and wasted little time climbing the single-seater ladder, driving a works Formula 3 March in the first season of the new decade. The speed was there, but broken ankles after a crash at Brands Hatch set him back. He returned to action in 1971 and set his sights on Formula 2, but with little success.

It must have occurred to him he was probably the wrong shape for an F1 hero but still he pressed on in F2, Atlantic and Formula 5000 through the first half of the 1970s. Perhaps the penny took a while to drop. But by 1972 he was also twirling an Escort around Silverstone in the RAC Tourist Trophy, to a third-place finish and class win. This was his future. An early association with Ford and a foothold in the British Saloon Car Championship would be the foundation upon which everything would be built. From the start he kept a tight grip on his destiny by preparing and entering his cars, supported fittingly by the Hermetite sealant brand.

“I did the odd race with him but didn’t know him well,” says John Fitzpatrick, tin-top wizard and a man who always knew the value of racing with a roof over his head. “Then he called me because he was involved in running a couple of cars for Ford at Spa in the 24 Hours, and out of the blue he asked me if I’d drive with him.”

Leading a pack in the 1974 BSCC opener at Mallory Park. Tom would win the Class C title in the Capri

Fitz and Walkinshaw were partners in a race that put the latter on the map – even if it was the former who did most of the work (at least on the circuit). “In 1976, Tom was involved in putting a deal together to run a BMW CSL in the new World Championship of Makes,” says ‘Fitz’. “I drove with him at Daytona in January – [BMW motor sport boss Jochen] Neerpasch put us together for that. They ran three cars, and those three cars were then sent to Europe. Schnitzer had one, Alpina had one and Tom had one.” Tom Walkinshaw Racing was up and running. The opening round was the Silverstone 6 Hours in May. But there was a problem: Walkinshaw had a clashing commitment. “Tom was also driving a Capri in the BSCC, and there was a race at Thruxton that weekend,” recalls Fitz. “So, I started the race, he arrived by helicopter, did an hour in the middle and then I finished it.” John not only finished it; he won a proper thriller – just. A late charge by the delayed Kremer Porsche 935 of Bob Wollek and Hans Heyer resulted in a winning margin of just over one second. “Another lap and we wouldn’t have won,” says Fitz. “The Kremer car would have had us. It was quite exciting, and then I was up on the podium on my own. We had no mobile phones in those days for me to let Tom know…” Walkinshaw would likely have been too busy to take the call anyway. Having flown back to Thruxton, his Capri headed Andy Rouse’s Triumph Dolomite to take a convincing BSCC win. The chopper flights had paid for themselves.

“I got on very well with him,” says Fitz, who raced with and against the best of the era. “We respected each other. There wasn’t really very much between us. He was very good technically, very good at setting up the car, probably a bit better than I was. In those days, I used to just drive what I was given. I was a little bit quicker than he was, but I’m talking tenths. In the race, that didn’t really matter. He was a good guy to drive with. A typically dour sort of Scot! But he was very good at putting deals together, and it wasn’t long before he got into the serious stuff.”

A works BMW drive in the 1976 Daytona 24 Hours helped launch TWR

Getty Images

His BMW connections tightened on the back of that Silverstone win. Through the late 1970s, his touring car and endurance racing career began to build a head of steam – but at this stage, he didn’t always drive for himself.

“From the start Walkinshaw kept a tight grip on his destiny”

Belgian long-distance specialist Pierre Dieudonné, another who had fallen off the single-seater ladder, first met Walkinshaw when they drove CSLs together for Liege- based Luigi Racing in 1977 – and inadvertently ended up at Le Mans. “We were on our way back from Brno where we had won,” says Dieudonné. “Both cars were in one piece, so Luigi took an entry at Le Mans. Times have changed. We arrived late for scrutineering, but they were quite flexible. The car was the slowest on the straight because we were only doing 280kph, but we managed to qualify towards the back of the grid. But it was very strong, my car – Tom was in the other one. It just needed fuel and tyres, and we finished eighth overall, first in the IMSA class.” Walkinshaw’s entry holed a piston. In four Le Mans starts as a driver, he would never see the chequered flag.

At this stage of his life, it was the Spa 24 Hours rather than Le Mans that would play a bigger role in the Walkinshaw story. His first win at the Belgian enduro was an unlikely one, in a Mazda RX-7 shared with Dieudonné in 1981. “Of course, he was the team leader and driving as his co-driver was a big advantage!” says Dieudonné, who remains active today in motor sport as sporting director with the crack WRT squad. “Tom’s car had the best chance to win, apart from the fact he was a brilliant driver. He was the boss and a winner in every sense.”

Victory alongside Dieudonné (Mazda RX-7) at Spa in ’81

DPPI

Back in the UK, he’d already delivered on his first-meeting promise to Percy, who would win a BSCC title for TWR in the RX-7 in 1980. “I first drove for him in the BMW County Series, and then it got serious with the Mazda,” says Percy. Why did Walkinshaw himself not drive in the BSCC? “I asked him ‘what are you going to do?’ He said: ‘That’s for me to know and you to find out’, which is a well-known phrase from Tom. He said he’d give me £6000, ‘but if you don’t win the championship, I won’t pay you’. I don’t think he had the money then.

“We ran two cars, and different drivers came and went. Some couldn’t put up with his brashness, and some he couldn’t put up with. He did actually give me a choice of partner in the other car for 1980, but whoever I came up with, he said: ‘That’s no good. Everybody will know everything about what we know.’ So he would turn people down if he thought they couldn’t keep things to themselves. That was quite important; you had to accept that.”

The next chapter of Walkinshaw’s life would kick off the most successful period of his career. Forget Benetton, Ligier and Arrows in 1990s F1; it’s Jaguars and Rovers in the 1980s for which Tom Walkinshaw should always be best remembered. But the memories are chequered in more ways than one, depending on who you speak to.

In 1983 Soper was stripped of BSCC title…

…but five years later TWR celebrated Le Mans win

In 1983, Steve Soper was fresh out of one-make racing and ready to burst into the touring car stratosphere. That year, in a TWR Rover, ‘Soperman’ blitzed the BSCC and won the Tourist Trophy at Silverstone to cap his arrival, only to lose the title months later over a technicality that wasn’t even performance- enhancing. “Okay, I lost the championship,” he says. “I didn’t care at the time. As far as I was concerned, I won it morally and fairly. We got chucked out on a nut and bolt that gave no extra horsepower, it just made the car easier to maintain.”

“Walkinshaw heard the criticism and benched Soper for months”

Soper was flying high in the mid-1980s at TWR, but it’s not a time he remembers fondly. “I had a one-year contract in 1983, and for 1984 I was offered a drive with BMW Germany. I didn’t take it. I got talked into staying where I was by John Davenport of Austin Rover. BMW sounded a bit daunting to me. JD said to stay with your friends, with extra money and a two-year contract. In hindsight, which is a lovely word, I think it was a mistake.”

Soper ended up offending Walkinshaw by offering what he thought was constructive criticism. The problem was the boss got to hear about it second-hand, and his hair- trigger reaction was to bench Soper for six months. It’s no surprise the relationship never really recovered. Soper retains respect for his old boss as a driver, even if affection is a stretch. “Tom was a very capable, competent driver – fast and quick,” he says. “He was clever at knowing how the car needed to be modified and developed. When the car was not right, he knew how to get it right.

“He was very strong, very stocky and had a huge amount of stamina, although he was probably not the fittest guy. The cars were set up for him, so if you couldn’t drive it the way he drove it, tough luck. The brake pedal you needed two feet to push, and none of the cars had power steering. Also, for those who drove with him, he wouldn’t move the seat. It stayed in his position.

“Was he a Jim Clark or Jackie Stewart? No. But he was certainly as good or even better than a lot of people out there. On equal terms, it was very difficult to beat him. But what he did was make it not quite equal terms. He would always have an advantage. And hey, if it was my team, I’d want the latest bits or best tyres. Whether he took that to the next level is for someone else to say.”

In truth, by the 1980s it was hard to unpick Tom Walkinshaw the race car driver from the team boss – because they were the same. Even his friends admit he could be a difficult man to drive for and with, as stories from TWR’s largely successful Jaguar XJ-S days attest.

Walkinshaw and Nicholson won Nürburgring’s ’83 ETCC round

In 1982, Walkinshaw led Jaguar back into the international racing arena in the European Touring Car Championship, now running to the new Group A regs. Burnt by the unhappy Broadspeed XJ6 experience of 1976-77, the grand old British carmaker – still under British Leyland ownership – had become an irrelevance in terms of modern motor sport. Walkinshaw and TWR changed all that in just three years, in a programme that led directly to an even greater one that took Jaguar back to Le Mans.

Percy, in particular, has happy memories, mostly. “I remember the first time I drove a Jaguar for him, doing three laps at Silverstone to see if I was any good for him,” he says. “I’d done a handshake with a mechanic because I wasn’t allowed to know what time I’d recorded and he was standing behind Tom: thumb up meant the time was good. Thumb down, nah, no good buddy. I’d done my three laps, and as I was getting out Tom said: ‘What do you think of my car?’ I said: ‘It’s very good, Tom, but is there any chance I could adjust the seat because I’m finding it very difficult?’ I’m long-legged and quite tall, Tom was short and stout, so I was floating about in the seat and up against the steering wheel, like a NASCAR. I was half-way out, and he said: ‘If you want to drive my car, you’ll drive it where the seat is.’ By the time he’d finished that sentence, I was back in the seat pretending it was perfect! And I got the drive. The thumb was up.”

The Jaguar ETCC programme gathered pace over the three years, Walkinshaw in particular notching up race wins and making enemies of his old colleagues at BMW. The car was competitive from that first season in 1982. Walkinshaw and Chuck Nicholson won four times, including the Silverstone TT, with Dieudonné among others providing able support in the second car.

The Belgian has mixed memories of his time with TWR. “At Luigi we’d had a friendly relationship, then when it came to racing for him you had to deliver,” he says. “In the early days of Jaguar, he really struggled to set up that deal and the car. In 1982, he had promised me the full ETCC, but he only had the money to run one car. Then he got involved with Chuck Nicholson, who was helping him out, and there was politics. Sometimes he needed to have a British driver because it was Jaguar. So, I was left a little bit in the cold. We did 1983, but I could feel the political pressure. It didn’t make me feel so happy.

“Tom would try everything to twist the wording of the rules,” he continues. “Every tuner is doing that, but he was like a fighter in a physical way. He could impose and impress more than other people, and at the same time, he was very clever in business and human relationships. He could use his strengths – but in a subtle way. It was a matter of being on the very edge of the rules and probably a little bit over… That’s part of the game for a tuner.”

Eggenberger BMW duo Umberto Grano and Helmut Kelleners had beaten Walkinshaw to the drivers’ title in 1982, but the following year TWR upped the ante. Among the drivers to bolster the team that year was a young ace who was also busy battling a Brazilian called Ayrton Senna in British F3. “Fast, very aggressive,” is how Martin Brundle remembers his old mentor as a driver. “Unsurprisingly, Tom was a supremely aggressive race car driver, and he’d got a turn of speed. That Jaguar XJ-S was a winning car, but it was an absolute monster to drive. It was quite an unruly car. But Tom was the boss of it. We used to smile a bit because Tom always had the best tyres, but wouldn’t you if it was your team? I certainly would have done. Tom made sure he had the best kit.”

Walkinshaw and Brundle won the Zeltweg ETCC round in 1983

One of the highlights of that second campaign was a victory at the Donington 500Kms – but this time Walkinshaw wasn’t in the winning car. He’d led before a long pitstop cost him, then Nicholson ran out of fuel… But then Brundle stepped up, as he would so often for Walkinshaw in the years to come. He, John Fitzpatrick and Enzo Calderari beat a trio of BMWs as Walkinshaw and Nicholson trailed in fifth.

Brundle’s account highlights how Walkinshaw would stack the cards in his favour – until he was out of the reckoning. “Tom had a special set of wets for himself,” says the 1990 Le Mans 24 Hours winner. “For one reason or another, I ended up in the lead in treacherous conditions, and Tom gave me those tyres, and we went on to win a mad, mad race. He wasn’t selfish from that respect; he saw the bigger picture for TWR.”

But by now, politics was undermining what was otherwise a great era of ETCC racing. Schnitzer and TWR would protest and counter-protest each other throughout a difficult season – and Fitzpatrick’s memories of just how far his old team-mate from Silverstone 1976 would push to win are telling.

“The first race I did with him was at Donington, and Martin Brundle and I won, which was great,” says Fitz. “The team was terrific. A couple of weeks later we went to Mugello, and before I got in the car for practice, a mechanic said: ‘I’ll just run you through everything, John.’ Part of this briefing was how to switch on and use the secret fuel tanks. We finished third in the race. I went to see Tom afterwards to tell him I wouldn’t be able to do any more races; and explained exactly why calmly. I didn’t feel happy because I was driving against my mates like Dieter Quester and I knew we were cheating, and I’d never cheated knowingly. He was fine – no problem, no aggro, he understood 100 per cent. I had a contract with him for the year. He paid it in full, probably to keep me quiet. We parted on good terms. I had no axe to grind.” Walkinshaw grudgingly lost out to Quester in the final reckoning; but told the now four-time ETCC champion: “We won’t give up. We’ll be back next year.” And now in full British Racing Green, so the TWR Jags would be: 1984 would be their year.

TWR raced with Jaguar at Spa in ’84

DPPI

At the Zolder season finale, Walkinshaw claimed the third place he needed to be crowned champion after a campaign in which the V12-powered XJ-S properly vanquished the BMW hordes. And the highlight was the Spa 24 Hours in July.

Percy picks up the story. “The XJ-S was different to any touring car I’d ever driven,” he says. “The grunt and power were there, and it was wonderful. They started off with 500bhp and by the end were up in the high fives. But you weren’t allowed power steering or servo-power brakes: everything was the way Tom wanted it, which was as basic as it could be, and I agreed with that. But you had to manhandle the car. Lots of people couldn’t get on with the XJ-S. You had to get hold of it by the scruff of its neck and make it do what you wanted, instead of relaxing as you would expect in long races. It certainly kept you fit. It was a lovely era of touring cars.

“As a driver, Tom was certainly hard on the machinery. That’s why he wanted a bullet-proof car. For example, bedding in brakes and pads. Wherever we were in the world, he’d say, ‘Winston, you’re up early.’ He wouldn’t do it. The boys didn’t want him to do it! He was too eager to get on with it, too heavy-footed.

“The only time I drove with Tom was with him and Hans [Heyer] at Spa when we won. We had two punctures, but we were about three laps ahead at the end, which was amazing. Nobody thought the V12 was going to win a 24-hour race. Hans Stuck and the BMW boys would say ‘Yeah, sure, you’ll be fast, but we’ll be there at the end’. What we agreed was that we would run at a pace we decided, rather than chasing the BMWs. You had F1 drivers and top touring car drivers, so they were going to race each other. Tom and the boys came up with a pace, and we stuck to it.

“In the night, when I was in the car, the fog came down. Alan Hodge from Jaguar went up the hill to the top straight, and as the Jaguar was coming up he would shine the torch across the track, which indicated the 200-metre mark. The fog wasn’t constant, it would swirl. You couldn’t tell from one moment to another whether it would be thick fog. Two of the leading BMWs crashed into each other, and we inherited the lead. They got going again but were now a few laps down. And we were able to sustain that pace until the very end – apart from those two punctures, one after the other.”

The victory at the biggest race of the year came in the same week Jaguar was freed from the shackles of British Leyland and floated into private ownership. “People say that race saved Jaguar,” says Percy with pride. “Lots of the staff have said that: ‘You guys saved our jobs, our mortgages, the lot…’ All of a sudden, people were buying Jaguars again.”

Walkinshaw’s best achievements for the brand were yet to come – and not at Spa in touring cars, but back where the Big Cat belonged: at Le Mans. By 1985, the XJ-S spell was over, as Jaguar chairman John Egan charged TWR with Group C and the race win that mattered. The best was yet to come.

Walkinshaw probably peaked as a driver in 1984. He remained player-manager for a while, but in TWR’s Rovers rather than Group C Jaguars.

Brundle & Co won Daytona in ’88

Getty Images

Given his abilities and physical strength, why didn’t he put himself in the XJR sports cars, too? The drivers don’t have a straight answer to that one. “Once we got to Group C he was team boss only, and that was a big programme,” says Brundle. “He was developing a lot of other business stuff too. Jackie Stewart tested one and crashed it. They were different animals with the downforce – they weren’t grip-limited in a lot of places. The finesse and technique to coax a touring car round, which is a skill in itself, is unique. But I don’t ever remember Tom getting in a Group C car.” Neither does Soper. “I think he possibly knew his limitations,” he says.

But Percy recalls Tom in a Group C test, in the first one, “the green one”: the XJR-6. “We were at Donington one day, and I was testing the Rover,” he recalls. “It was about 4pm. Hans Heyer was there in the Group C Jaguar but had to go and catch his plane, so Tom was getting ready to get in the car. I said: ‘Can I have a go?’ ‘No.’ ‘Ah come on, Tom’. ‘No’. In the end, he said, ‘Tell you what, if there’s time before they close the track you can have a go’. He got in the car, put it into gear, down the pitlane – bah, bah, bah, bah, on the rev limiter – and off he went around the circuit. His second lap was quicker than Hans had been all day! That was Tom – wrung its neck. You know, he came in at two minutes to five – and the track closed at five. ‘You can get in now,’ he said. I was gutted. I got in my car and drove back to Weymouth.”

Working with Brawn at Benetton in the 90

Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images

The pair also got together at Jaguar in Group C

Darrell Ingham/Getty Images

So many Walkinshaw stories turn out bittersweet and, even for his friends there were times when he was hard to like. But respect, whether it was as a driver or team patron, was always there. “I never really gelled with him,” says Soper. “I would almost say I didn’t get on with him. I had a problem with him in the 1980s. However, whether I liked him or not – and I don’t want to say I didn’t like him – I admired him for what he was able to do and achieve.”

Percy offers one more telling insight into the ambition that would push Walkinshaw to the limit and beyond during his long career at the top. “As a chum, as a friend, he could be quite hurtful because Tom was out to build an empire,” he says. “I did say to him one day in the early 1980s ‘what are your dreams, what do you want to do?’ He said: ‘I’ll be in F1 one day’. That was his dream, and I’m afraid it destroyed him. He should have stuck with sports cars, as should Jaguar.”

Walkinshaw’s TWR empire crumbled with his folly at F1 team Arrows in 2002. Then eight years later he was gone, ripped from his friends and family by cancer. But those final chapters are not how they will remember Tom Walkinshaw, and neither should we. Images of the burly Scotsman manhandling an XJ-S around Spa or his beloved Bathurst are so much more fitting. The last word goes to Brundle, who will always see the best in his old mentor.

“He was mighty in the Rovers and the RX-7s,” he says with a smile. “Tom’s type of car was one you picked up by the scruff of the neck, like the XJ-S. And, of course, he had the stamina to spare, which is why in something as tough as the Spa 24 Hours he was so great – a bona fide professional-level racing driver.

“There’s a theme, isn’t there? All those cars that needed manhandling…”

Walkinshaw pictured at Arrows in 1996; six years later its folding would lead to TWR’s collapse

Darren Heath/Getty Images

Australia’s Great Race, the Bathurst 1000, was a grail for Tom Walkinshaw during the Jaguar XJ-S years. He never did quite conquer The Mountain as a driver, but his team managed the feat, much to the chagrin of the locals who had considered him an interloping nemesis.

“Bathurst meant a lot to him,” says Win Percy. “He took me over in 1984 when I didn’t have a drive. He was driving John Goss’s Jaguar, and the

clutch went on the start line [causing a pile-up and a race stoppage in the process]. On the way home he said: ‘We’re going back next year to win, mate’. Are we? ‘Yep.’” By 1985, Jaguar had dropped the touring car programme to focus on Le Mans, but Walkinshaw brought the XJ-S out of retirement to enter a three-car team Down Under.

“Around the mountain it was lovely to drive; you could get into a proper flow,” says Percy. “We were leading by a lap, and the blasted oil cooler split just before the end. We repaired it, but it dropped us back and we finished third. The oil cooler was bolted securely to a cross-member, but through the Dipper the body of the car was twisting so much the cooler fractured.

“Luckily Armin [Hahne] and John Goss won it in another Jaguar. In Sydney, the day after, we went up to the Jaguar dealer to say thanks for looking after us, and people were queuing up to buy these cars that won Bathurst. It was incredible: win on Sunday, sell on Monday.

“Tom Walkinshaw was like a second father to me. Win Percy and I were close to him, I think, because we got the job done and because we also stood up to him a bit.

“A lot of people have got a lot of things to say about Tom, but he never let me down. Never on anything. I wrote to him when I was 19 and asked him if I could have a go in the County Championship car at Snetterton, out of the blue –and he put me in the car. That put me on the map. We had that affinity from those early years.

“The last time I raced for him would have been 1997 in the Le Mans Nissan – so from 1979 to 1997, I was driving his cars, more on than off. The weirdest thing he ever asked me to do was the Nürburgring Nordschleife in the Jaguar XJ-S. He rang me up, and he said: ‘I need you over here’. ‘I don’t know the Nürburgring, Tom,’ I said. ‘The plane is already on its way’. He said he’d show me around – and I was standing in the pitlane shivering in fear. I knew the first corner, and that was it – there were no PlayStations back then. Sure enough, Tom comes in, and the XJ-S is ticking over. He said: ‘Follow the pussy cat’s tail’. And then Enzo Calderari crashed my car on the in-lap. Relief! I know I would have crashed that car, guaranteed… The thought of driving that XJ-S around there is out of the question. But he was going to teach me.”

Brundle’s last TWR outing ended in retirement at Le Mans in 1997

DPPI