The T.M.C.

Sir, Your correspondent Mr. Frank Farrington mentioned this company in relation to the Wilkinson motorcycle. This was not, in fact, designed by Mr. Ogston, but by the Engineering Department of…

Wickham picked Bentley Le MAns win as his career highlight during 2020 Motor Sport interview

Jakob Ebrey

He co-owned the Spirit Formula 1 team in the early 1980s, helped mastermind Audi’s successes in the British Touring Car Championship in the mid-1990s, was at the helm of the Bentley set-up that won the Le Mans 24 Hours in the 2000s, and went on to put together and then run the A1GP World Cup of Motorsport over the second half of the same decade. John Wickham enjoyed an eclectic career of which those are just the highlights.

Wickham worked across a range of racing arenas all around the globe for nearly 50 years. He managed teams in Formula 2, Formula 3000 and multiple touring car categories, and ran sports car programmes on both sides of the Atlantic. And he was still going strong with few thoughts of retirement as he approached 70 before being diagnosed with motor neurone disease.

We meet at the Lambert Arms, not far from the care home close to High Wycombe where John has lived since shortly after his diagnosis in 2019. He opts for the chicken liver pâté with red onion marmalade followed by the beer-battered haddock.

Brought up in Petts Wood near Bromley, Wickham had an early interest in motor sport.

“My father had raced motorcycles between the wars at places like Crystal Palace and the original grass track at Brands Hatch,” he explains. “I was reading the magazines from the age of six, and then got the Scalextric set and started modifying the cars. I even organised a sweepstake on the result of Le Mans when I was 13 or 14.”

1973 was Wickham’s big break, in F2 for Surtees with Mass as lead driver

His first involvement in motor sport came with junior membership of both the British Racing & Sports Car Club and the British Automobile Racing Club in his mid-teens, helping at nearby Brands and Crystal Palace.

“I started working in the paddock before I was old enough to go trackside as a marshal,” he recalls. “I can recall being at the memorable races: the amazing drive from Pedro Rodríguez in one of the Gulf Porsche 917Ks at the BOAC 1000 in 1970; and the World Championship Victory Race in 1971 in which Jo Siffert died.”

There was a short-lived dabble as a competitor, navigating on road rallies with a Mini-owning friend. But working in motor sport rather than banking — he was employed at a National Westminster branch in Covent Garden after leaving school at 18 — was very much the aim for the young John Wickham.

“I saw a small ad for a position at the BARC,” John recalls. “I was mad about motor sport and thought it had to be more fun than banking. I remember hand-writing my application to [general manager] Grahame White.” It might sound incongruous today, but the club’s offices were in Argyll Street in Soho, right next to the London Palladium. From the centre of London, the BARC’s new competitions manager helped organise 20 race meetings through 1972.

The ambition, however, was to progress from running race meetings to running a race team: “Formula 2 or sports cars, I was thinking.” White’s departure from the BARC over the winter of 1972/73 made Wickham decide it was time to seek new pastures.

Another ad in a mag resulted in a trip down to Edenbridge in Kent to see John Surtees, who was looking for a team manager for his F2 squad. “Surtees for some reason gave me the job, even though I’d never been near a race team,” recalls John. “The team was John, one mechanic for each car, a truckie and me.”

He oversaw a programme with a pair of TS15s powered by Hart-tuned Ford BDAs for Jochen Mass aboard the team’s lead car and a roster of drivers including Mike Hailwood, Carlos Pace and Derek Bell in the second. It was a busy schedule for the rookie team manager: Team Surtees raced in 16 of the 17

rounds in the 1973 European F2 Championship. Mass won two of them and scored a further four podiums, though ended up a distant second in the championship to works March driver Jean- Pierre Jarier. There were some scrapes along the way, most notably when the German was disqualified from the two-heat Thruxton race in April.

“Jochen’s engine blew in the first heat, so we swapped cars. We put him in Hailwood’s car for the second race and said it was Mike who’d blown up. Of course, we were found out. That was John’s idea.”

Surtees and Wickham had another brush with officialdom at Enna in late August. “We built a new chassis that was meant to be more aerodynamic. The truck had already left by the time it was finished, so we trailered it to Sicily only to be told at scrutineering that the car was a centimetre or something too wide.”

The rest of the team travelled on to the Salzburgring in Austria for the next round, while Wickham was tasked with towing the new car the 1500 miles home on his own.

“The first morning, I went down to the beach and had some melon, which turned out to be infected. I was sleeping in the van, and when I woke up I’d have to jump straight out for obvious reasons – I wasn’t very well. When I got back, the doctor told me I had dysentery. I was in bed for a week and a half. In those days there was prize money, all in cash. After a week or so, a police sergeant knocked on the door and said, ‘Mr Surtees has accused you of stealing the money’.”

Wickham decided that Team Surtees wasn’t for him and left at the end of the season. It was then back to the BARC, now based at Thruxton and run by Sidney Offord. Offord oversaw a massive expansion of meetings organised by the club: “Sidney realised that the only way to make more money was to hold more meetings. We went from 19 meetings in my first year back in ’74 to 29 in 1976.”

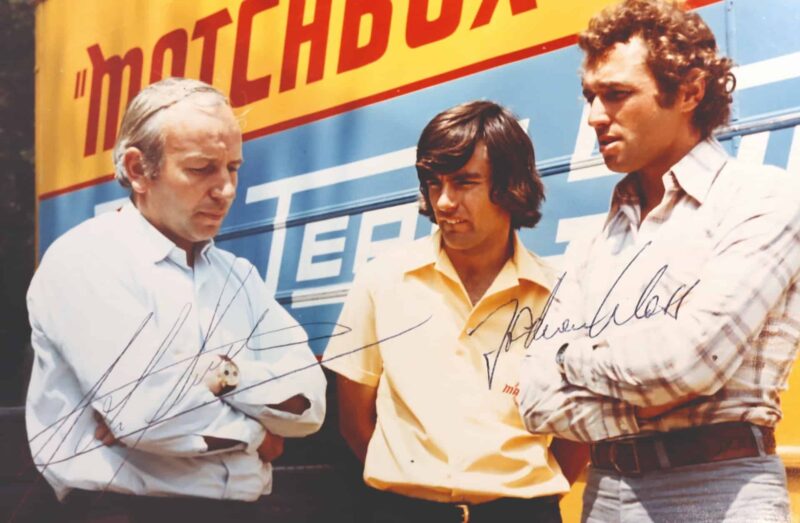

Wickham (third from right) oversaw Gachot’s (second from right) ’88 F3000 bid at Spirit/TOM’S

Jakob Ebrey

The next role in the pitlane for Wickham would also be in F2. Thruxton’s place on the European calendar meant Wickham was present at an F2 association meeting at the end of ’78. March co-founder Max Mosley asked if he might be interested in helping the team out: “I thought, perfect!” Wickham was a team manager again, but his remit this time went further. He also engineered one of the flotillas of works cars that March ran.

Marc Surer won the title in Wickham’s first year in the job aboard a BMW-backed factory March 792. It was a close battle with Brian Henton in one of the Toleman team’s Ralt-Hart RT2s, the Swiss coming out on top courtesy of the British driver losing victory at Enna after missing a chicane at the start. “Henton was excluded, and Toleman appealed, but got turned down. It probably helped that Sidney

was a steward,” recalls John. “He was there because he could speak Italian.”

The following year March built an 812 F2 powered by the new Honda V6 engine with

which Ralt and Geoff Lees won the European title. That resulted in Wickham coming into contact with Nobuhiko Kawamoto – the architect of Honda’s return to four-wheel racing and a future CEO of the company – when he visited Japan to oversee Satoru Nakajima race the car. “Kawamoto asked me out to dinner and told me he wanted a team that was focused on F2, not building all sorts of customer racing cars like Ralt,” recalls John. “He asked if I would be interested.”

Wickham was, and hooked up with former McLaren F1 designer Gordon Coppuck, who’d joined March in 1981, to start what became Spirit Racing: “Kawamoto asked what we would call ourselves. We were driving somewhere in Tokyo, and I saw a Bridgestone advert that read, ‘Come on racing spirit’. I thought Spirit might be good.”

Coppuck designed a new F2 car for 1982, while Wickham put together the team and looked for the other half or so of the budget that wasn’t provided by Honda. The two Spirit-Honda 201s would end up running in Marlboro livery by coincidence. Wickham successfully went after Thierry Boutsen and Stefan Johansson, who were each sponsored by the Philip Morris company in their respective homelands, because “they were the best two drivers available”.

The honeycomb-chassis Spirit with a Honda engine and Bridgestone tyres was the class of the field, with eight poles from 13 races. Johansson didn’t win a race after encountering the lion’s share of Spirit’s reliability issues. Boutsen, on the other hand, finished all bar one of the rounds, notching up victories at the Nürburgring, Spa and Enna.

The Belgian looked on course for the title at the Misano decider, only for rain to derail Spirit’s championship bid.

“The Bridgestone slick had gone to a radial construction, but the wet was still a cross-ply,” explains Wickham. “When we went to wets, we had to change the ride-height by a few millimetres, but obviously we couldn’t do that during the race.” Boutsen slipped to sixth, and the title went to March driver Corrado Fabi. But by then Spirit was already looking beyond F2: it was working on a car that would take Honda back to the pinnacle of the sport.

“Honda asked me to go to Tokyo and told me they were going to go into F1. They gave us a choice: you can stay in F2, or you can have a deal to run a test team, which might lead to an F1 race programme. We opted for the testing because it was a way to get into F1.”

The first Honda F1 twin-turbo V6 ran in the back of a car, a converted Spirit 201, at Silverstone that winter. The date was November 24, John’s birthday: “You need to set yourself deadlines, otherwise things slip, so I picked my birthday.”

Wickham and Coppuck were lobbying to go racing through a winter test programme that took them as far afield as Riverside and Willow Springs in California. It was helpful that there was a non-points race in April, the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch: “I told Honda they would only be able to tell how good the engine was if they went up against other people.” Spirit entered the Brands event with Johansson taking driving duties. The Spirit- Honda 201C suffered engine problems in both qualifying and the race, the car stopping after five laps with a turbo seal failure. “Brands was a one-off, so I pushed to do the second half of the season. They told me they would think about it, but at the same time revealed they were already talking to Williams about 1984.”

Spirit made its F1 debut with Johansson in ’83 British GP

The go-ahead for Spirit to join F1 with a one-car effort for Johansson from the British Grand Prix came as the entry deadline approached: “I ended up sleeping on the office floor in Slough. I knew the decision was coming by fax overnight.” Spirit turned up for its grand prix debut at Silverstone with a new car, the 101, effectively a beefed-up F2 chassis with an F1-sized fuel tank. Spirit’s best result of the season came at the Dutch GP in August at Zandvoort with seventh. The same month, Spirit learned it wouldn’t have Honda engines next year.

“My understanding is that Frank said no to Honda having two teams,” recalls Wickham. “It was a pity because we had sponsorship from Skoal Bandit [a chewing tobacco brand being launched in Europe] and free tyres from Goodyear if we kept the Honda deal. It was all coming together to run one car if not two.”

Honda, once again, offered Spirit a choice: “We could go back to F2 with their support or, if we decided to stay in F1, they would pay for four engines from another manufacturer.”

Spirit opted to remain in F1 with Hart’s straight-four turbo. There was no tobacco money, sponsorship guru Guy Edwards had taken it to the RAM Racing team, and Pirellis, in place of the Goodyear tyres. “It was a way of staying in F1,” muses Wickham. “Dropping out and trying to get back in isn’t easy. It might have been the wrong decision…”

Spirit ran Mauro Baldi initially, then Huub Rothengatter for eight races, before the Italian Grand Prix of 1984. Four eighth positions for the Spirit-Hart 101B were the best results of a season when “money was always a problem”. The team made it into ’85, but with debts mounting it ended up selling its Pirelli deal to Toleman – which had been left without any tyres – and ended its season after three races.

“Our overdraft at Barclays was something like £80,000, and they said they were goingto foreclose on us, and there were other debts, too,” recalls Wickham. “We also owed money to Baldi’s manager, Nicolo di San Germano, and he brokered the Toleman deal. The money we got cleared everything we owed.”

Spirit intended to get back on the grid for 1986. Coppuck continued work on a new car and, when an F1 return looked increasingly unlikely, set to on a Champ Cars Indycar. “Gordon found someone in the States who wanted to invest in an Indycar,” John explains. “That was designed, but never got beyond a wooden mock-up. Then we basically ran out of money and closed the company.”

Wickham’s career took a new direction in ’86. Di San Germano looked after sponsorship for the Nordica ski equipment manufacturer, which ended up on the side of the works Volvo 240 Turbos run by the Belgian RAS Sport squad. The Italian recommended bringing in the Brit to bolster a team that was moving up from the lower classes of what was known simply as the ETC.

Homologation rows over the Group A rules dogged the series at the time: “That year we were in court in Vienna, Paris and London.” There were three wins along the way, plus two lost to disqualification, but Volvo again failed to win the Spa 24 Hours: “Spa was a nightmare. We had bottles thrown at the cars at the old Bus Stop chicane, and I never found out why. We had two broken windscreens.”

A trip to the Far East at the end of the season sent Wickham in another direction for 1987, just as it had six years previously. RAS fielded the Volvos in the end-of-season Macau Guia and Fuji InterTEC races. It was here that John met the founder of the Japanese TOM’S organisation, Nobuhide Tachi. He was in the process of ramping up a UK operation together with Glenn Waters, who Wickham joined for 1987 to oversee programmes in touring cars, Formula 3 and sports cars. For the first time, Wickham would go to Le Mans, a quarter of a century or so on from organising that sweepstake.

TOM’S ran a pair of Dome-built Toyota 87C Group C chassis powered by Toyota engines in the French enduro. Neither got beyond hour six. Wickham was running the car driven by Alan Jones, Geoff Lees and Eje Elgh, which ran out of fuel at the end of its opening stint. “The team still had the fuel read-out in the car set to the length of Suzuka, I think,” says John. “Jones was being shown he could do one more lap on the fuel and ran out.”

Wickham opted to leave Norfolk-based TOM’S after two seasons because he “didn’t really enjoy jumping around between different programmes”. He now linked up with British driver Steve Kempton for an F3000 assault in Europe under the Spirit TOM’S banner.

Wickham parted company with the team in the summer and briefly went back to March to work on “various projects”. His Japanese links subsequently resulted in him establishing the Footwork team for an F3000 programme in Europe for ’89. Midway through the season team owner Wataru Ohashi decided he wanted to move up to F1: “He gave me a budget, what you would now call a pittance, to go out and buy into an F1 team.

Wickham met with Ken Tyrrell and Jean-Pierre van Rossem, the maverick sponsor of F1 rookie operation Onyx, who’d taken a majority stake in the team mid-season. “Ken told me that it wasn’t enough for the stake we wanted and van Rossem, who was wearing some kind of gown when I met him, told me he didn’t need our money. We ended up going to Jackie Oliver at Arrows. I was initially the sponsor’s representative, but then Alan Rees decided he didn’t want to go to races and I became team manager during 1990.”

Footwork’s F1 stint is always associated with the disastrous Porsche 3.5-litre V12 unit that came on stream in 1991. Wickham recalls he and Arrows designer Alan Jenkins having very early doubts about the engine. “The third time we went over to Stuttgart, both of us said as we were flying back ‘not sure about this’. We didn’t dare tell anyone else, because the Japanese wouldn’t have liked our concerns.

There were quite a few non-qualifications in the first year with the Cosworth car: when Michele [Alboreto] and Alex [Caffi] non-qualified in Adelaide [in 1990], Jackie and I went fishing on race day. The first half of 1991 was a disaster. The engine was a boat anchor: it was heavier than a Cosworth DFR, less powerful and thirstier. But when the definitive Porsche-powered FA12 arrived at Imola [round three], Michele had his massive shunt in practice at Tamburello when the front wing failed. We saw a problem when he passed the pits and called him in, but it was too late.”

The team, now called Footwork, dropped the Porsche engine after six races and reworked the cars for the Ford DFR.

“Porsche said they were going to come back with something better. That went on for about four months, and then they said it wasn’t possible. I think the deal was about £5m a year and we got it back, or at least Ohashi did.” Wickham remained with Footwork until the end of 1994. His final season might have been more successful but for aerodynamic rule changes that followed the deaths of Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna at Imola and the accident in Monaco that left Karl Wendlinger in a coma.

“In Brazil, we qualified sixth and 11th and then ninth and 13th at the Pacific GP and finished fourth with Christian Fittipaldi [in the Ford-engined FA15]. We soon started slipping back and stayed back. We seemed to suffer more than most with the reg changes.”

Wickham left Footwork at the end of the year and briefly looked after Ohashi’s charge,

Aguri Suzuki, at Ligier, while also working for Nissan Motorsports Europe, overseeing its Primera Super Tourer project in Germany and Spain. That led into the touring car programme for which Wickham is best known.

Richard Lloyd, a race winner in the British Saloon Car Championship in the 1970s as a driver and world series sports car events in the ’80s as a team owner, had business connections with Audi and played a key role in bringing it to the British Touring Car Championship. It wasn’t the initial plan, but he ended up putting together the Audi Sport UK team that ran the programme in 1996-98. “Richard met me in a pub near Brackley and said, ‘you know about touring cars, you could help put a team together’,” recalls Wickham. “Wolfgang Ullrich [Audi Sport boss] had told Audi UK he couldn’t find a team to trust over here, so we persuaded him we could do it.”

Star Audi driver Frank Biela was sent over to race one of two Audi A4 Quattros fielded in

the BTCC. The German won the 1996 title at a canter aboard the four-wheel-drive machine, winning eight times and notching up a further 12 podiums across the 26 races. “I got told off by Ullrich at Thruxton for winning by too big a margin. He said, ‘that’s not how you do it’. Frank knew the car really well and learnt the circuits very quickly.” Wickham said 1997 was “more difficult” after the weight penalty for using all-wheel drive was increased, and ’98 was “impossible” because it was banned.

Audi exited touring cars at the end of 1998 for a new path in sports cars. Lloyd had a hand in the move and planned to go to Le Mans in 1999 with two different cars, the open-top R8R LMP car machine in Germany and run by Joest and the British-built R8C coupé fielded by Audi Sport UK. “Richard and others persuaded Audi that it wasn’t clear if an open car or a coupé was the way to go. Richard took Audi up to the old TOM’S facility in Hingham. They liked it, so they bought it.”

The go-ahead for the R8C at what became Racing Technology Norfolk came late. The car was barely tested ahead of the Le Mans pre- qualifying day in April, but both cars made the cut. But the race wasn’t a success, gearbox issues putting both cars out early.

The R8C project came to an end as Audi focused on developing a brand new LMP car in Germany, the all-conquering R8. Wickham had “another one-year programme” running Stefan Johansson’s new sports car operation that fielded a pair of Reynards in the American Le Mans Series and at Le Mans in 2000 before rejoining Lloyd.

But RTN was working on a new closed-top prototype. The car was designed for a W12 engine, the pet project of Volkswagen Group boss Ferdinand Piëch, that was quickly halted. Brian Gush, Bentley’s head of powertrain and a motor sport fan, resurrected the project with a supply of Audi engines.

Lloyd and his renamed Apex Motorsport squad were brought in to run what became the Bentley EXP Speed 8 at Le Mans in 2001 with Wickham as team manager. Bentley claimed a podium first time out with the EXP Speed 8 shared by Andy Wallace, Eric van de Poele and Butch Leitzinger, albeit over 10 laps behind the winning Audi. Wickham reckons it was a good result: “We really weren’t sure where we were going to end up. Third was good, and we did manage to lead the race early on.”

The result owed a lot to the mettle of 1988 Le Mans winner Wallace and the cap from a bottle of Evian or similar. “A small hole was allowing water to get into the gearbox electronics and the cars were getting stuck in gear. We were lucky to find something that fitted the hole. Guy Smith got stuck in sixth and didn’t make it back, but Andy used all his experience to get his car to the pits when the same thing happened to him. He knew everything about that race.”

Wallace, van de Poele and Leitzinger were fourth a year later aboard a solo Bentley entry with an updated EXP Speed 8. An all-new machine, the Speed 8, followed for 2003, the year of the big push from Bentley as sister marque Audi’s factory presence came to an end. As Audi stepped up its involvement in Bentley’s campaign, Wickham’s role changed.

Wickham on the pitwall at Le Mans 2003 when Bentley dominated and sealed a 1-2 finish

“At the end of 2002, Ingolstadt asked if I would become a Bentley employee. They wanted me to move to Norfolk and be absolutely full-time on the programme.”

The Bentley set-up changed, too. Joest was brought in to run the car shared by Tom Kristensen, Rinaldo Capello and Smith. The Apex crew still looked after what was dubbed the ‘British’ car driven by Johnny Herbert, Mark Blundell and David Brabham.

Bentley dominated, finishing 1-2 as Kristensen notched up his fourth Le Mans victory in a row aboard the #7 entry. It could have been different, however. “The #8 was as quick, sometimes quicker. Johnny was the fastest on the averages of all of the drivers. But that car had a headrest come lose early on and then battery problems [it was replaced twice].”

Job done, Bentley’s programme came to an end with its Le Mans victory, but Wickham was back at the Circuit de la Sarthe 12 months later after he was brought in by Zytek Engineering to put together a works team to run a short programme of events with one of its 04S LMP1s. During the race, he made the contact that led to the next phase of his career.

He met the founder of the A1GP World Cup of Motorsport, Sheikh Maktoum. The introduction was made by sometime F3000 driver Stephen Watson, who was advising the Sheikh and looking for somewhere for him to sign a contract.

“Our car was already out of the race and Stephen, who I vaguely knew, asked if he could use our motorhome and said I could stay ifI liked. It turned out the contract was for a supply of Zytek engines for A1GP and Stephen asked me if I wanted to run the test team with the new Lola A1GP car.”

Wickham thus became employee number one of A1GP Operations Ltd, ran the test programme and then continued as general manager, technical and operations right up until the demise of the series in 2009. That meant running the show on the ground as it travelled around the world. “There were always doubters, but we had two, if not three, really strong years. The races were good and well attended, and we had the funding coming in.”

The situation changed when series boss Tony Teixeira did a deal with Ferrari for a supply of engines for a new car, supposedly modelled on its 2004 F1 design, for 2008/09.

“We assumed it was going to cost a lot of money, and it did. It was meant to have a design element of an F1 Ferrari, but the Ferrari badge we put on the nose of the first car was ripped off at Maranello.”

The series made it through one season with the so-called ‘Powered by Ferrari’ machine until mounting debts resulted in A1GP Operations being put into administration in May 2009. A calendar had been announced for 2009/10, and despite Teixeira’s claims that the money was in place to continue, the World Cup of Motorsport withered and died.

After A1GP Wickham had two forays back into the world of F1 either side of a stint evaluating a sports car built by Russian manufacturer Marussia, later involved with the Manor F1 team, for GT racing. Then came a phone call from Gush at Bentley.

“They were looking at GT3, and I brought in Graham Humphrys to do an evaluation on the Continental. Brian always says he doesn’t like southerners and suggested M-Sport [which is based in Cumbria] as a potential partner. I was thinking more of people with a background in sports car racing, but when we went there and saw their facility it was quite obvious that they could do it.”

Wickham was team manager with M-Sport’s factory team in 2014 and ’15 for its Blancpain GT Series Endurance Cup campaigns and subsequently worked with the German HTP and Abt teams on their customer programmes, remaining with the marque until the beginning of 2019. Wickham picks the Le Mans victory with Bentley in 2003 as the highlight of his career. “Owning an F1 team was short-lived and even shorter-lived as a works team,” he says. “Le Mans was a race I’d followed since I was young, so it finally came good.”