Racing Lives: Andy & Julian Rouse

Andy and Julian combined for Britcar success in 2003

Paul Cherry

Andy Rouse managed to combine racing and business to great success, taking four BSCC titles in 1975, ’83, ’84 and ’85 and breaking records along the way. Below the headline success, Rouse was a shrewd operator who set up Andy Rouse Engineering, honing all the skills he had learned in his early days working with Broadspeed and Jaguar in particular. His links to motor sport remain through son Julian, Arden Motorsport’s general manager, who rose up the ranks of management after an early foray in racing. The pair even drove a then-11-year-old Mercedes DTM car together in a 2003 Britcar campaign…

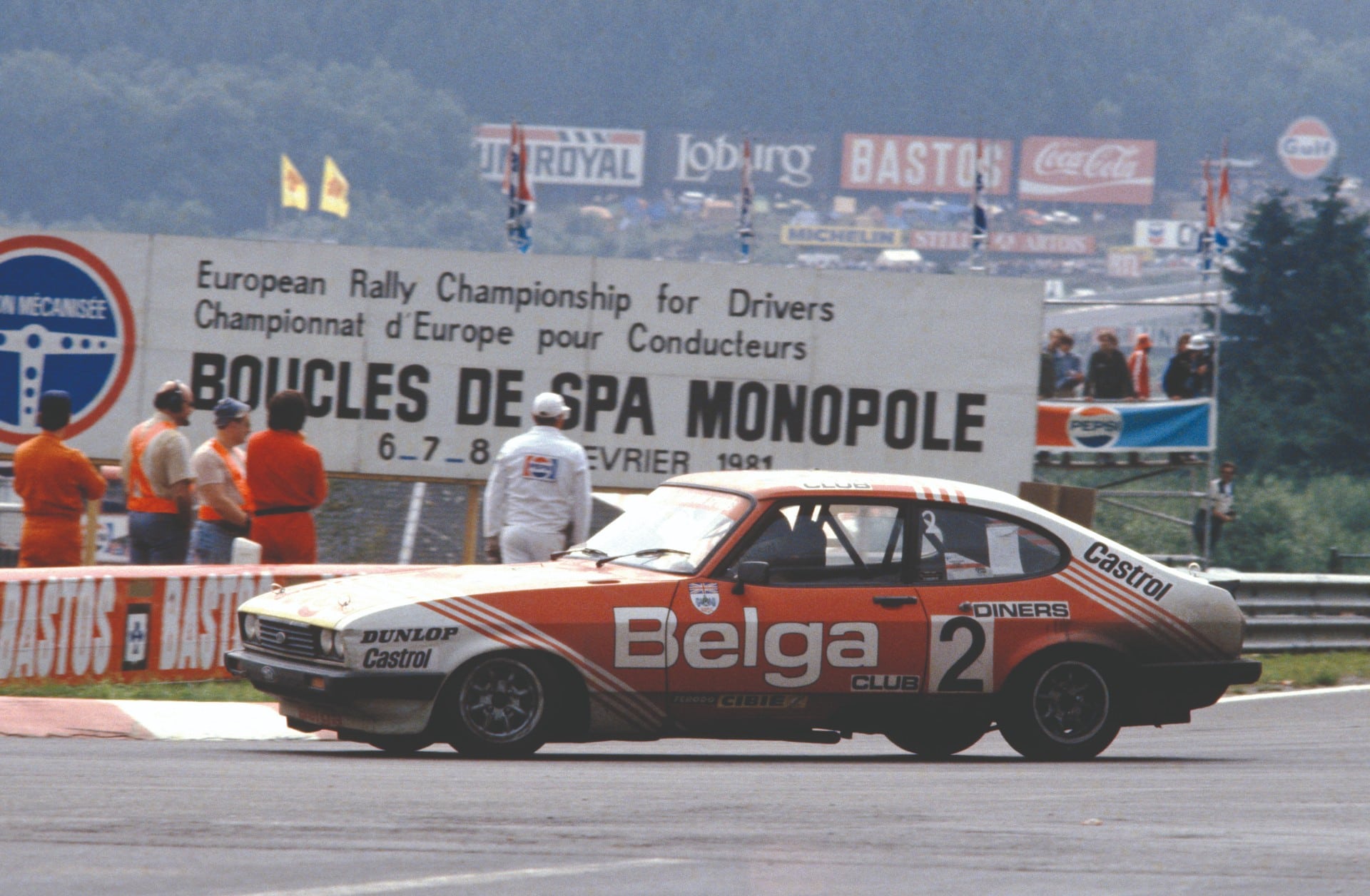

ANDY ROUSE: “There were many times when being an engineer gave me an advantage in racing, although not always how some might imagine. One of my big breaks came when I started driving with Broadspeed in the 1970s. Ralph Broad’s team had the deal to build the Jaguar XJ12C for the European Touring Car Championship, and I raced with Derek Bell.

The Jaguar weighed about 1450kg, had a big V12 over the front axle and no power steering. Worse, it had 19-inch wheels – 19 x 12s on the front and 19 x 14s on the rear – at a time when most road cars were on 13-inch wheels. It was a serious effort to drive, so much so I needed to do something about it, so I designed and built myself a training machine.

It was a seat on a frame with a steering wheel attached to springs, and it allowed me to exercise all the muscles I needed all in one go. It would improve everything from grip and thumb strength, to arms and shoulders, all at once, in my garage at home. I’ve still got it!

That make-and-mend mentality came from being brought up on a farm, where my father worked as a market gardener, growing tomatoes, lettuce and so on. So there was a private road to drive on, sheds to work in and things like tractors and ploughs to tinker with.

As a lad, when I was 14 and 15, I’d cycle for miles to go and watch jalopy racing. We’d head off to see clubs put on events at Gloucester and Forest of Dean, and while at school I built my own jalopy racer, a Singer special, which I bought from a local garage for £10, with a Ford Kent engine. It was a bit like a Morgan, with an aluminium body over a wood frame, and I stripped it all down to install a roll cage.

My best mate from school, Ian Bisco, would help me, but I don’t think anyone else of our age was doing anything like that at the time. Ian went on to run Cosworth in America, so it must have been a good grounding.

Because of that, I learned my craft racing on grass fields, which is like driving in the wet. You have to get the car set up nicely otherwise you can’t do anything, as there’s a big difference between it being right and wrong. It all came naturally to me, somehow.

It’s because of racing that I came to end up working on engines at Broadspeed in 1971. I’d gone to Ralph to buy an engine for my Dulon Formula Ford, ended up with a job, and Ralph sold me an Escort Mexico at cost price so I could race. I couldn’t have been at a better place to prepare it, and off we went and won the ’72 championship, and one thing led to another with drives in saloons.

Mind you, Ralph did pretty well out of it, because the Mexico Championship went across Europe, and Belgium in particular would send cars to Broadspeed to prepare. There were so many that eventually we had to send some back because we couldn’t manage them all.

I wanted to teach Julian the right lessons when he started in karting. He was good; we did the TKM championship, mainly, in Juniors and Seniors, and he raced well. But it was hard work, and it was at a time when I was flat out. All the same I didn’t want to pay somebody else to take him racing, I wanted us to spend time together and learn. We were at the same meetings as Lewis Hamilton and his dad, and got to know them well over a couple of seasons. It’s pretty professional and cut-throat-competitive now.

When the family came along I had to think about the practical arrangements at the races. If I hadn’t taken them with me, the only time I’d have seen the children would have been at breakfast before I went to work and they went to school. My days were long, especially after founding Andy Rouse Engineering, and the weekends were spent at circuits.

So once they were two or three years old, we bought a motorhome and that used to be our base for the weekend. It was a civilised way to go about it, because it gave us a place to go through the day and later, once everybody had gone back to their hotel, we’d light the barbecue and the kids would be on their motorbikes, messing about and having fun.

The highlight had to be racing in the BTCC in the mid-1990s, when it had become a series of international standing. And the Sierra Cosworth RS500 was my favourite car, but it was hot, hard work driving those. The floor would reach 60deg C, and after about 10 laps you couldn’t keep your foot on the floor because of the heat-soak. In the right-hand drive cars you’d be sitting on the same side as the turbo, with just a thick piece of sheet metal between you, the exhaust was running underneath and it was so severe I wouldn’t wear fireproof underwear, had to have an open-face helmet, and always kept the window open – I was dehydrated at the end of a race.

There were a lot of setbacks along the way, whether it was Jaguar pulling out of racing in 1978 and not having a drive, or losing the Ford contract in 1996 when I was running Andy Rouse Engineering. I kept faith, because I knew what I wanted and where I wanted to be, so it was a case of making the best of it.

One of my lasting memories from racing is getting home, late on a Sunday, picking up the sleeping children and tucking them in.”

Julian’s path took him to Arden, where he oversaw the likes of Daniil Kvyat’s pre F1 career

Grand Prix Photo

JULIAN ROUSE: “I was born into attending circuits right you have this nostalgic feeling of being a travelling family. It was great fun seeing so many different places at a young age.

We didn’t see a lot of Dad in the week. Around the time my sister and I were born he set up his own team, so he had responsibilities in the business, as well as the technical aspects, and had to stay fit to drive.

His life was different from other racing dads, who were employed by a manufacturer and weren’t necessarily that involved outside race events. My mum, Sheila, was supporting the business, handling the administration and bookkeeping, so it was a family effort.

We spent plenty of time with him at the Andy Rouse Engineering facility in Coventry, around the cars and the workshop. But this way of life meant that if we’d driven over to Snetterton in the motorhome and Dad had a shit race weekend, the joke was you probably wouldn’t hear him speak until Wednesday, let alone driving back from Snetterton!

Racing was more family orientated then, and the family would be more involved, certainly compared to what I experience today with the professional drivers I work with at Arden and R-Motorsport. When we were young we built up friendships with Peter Hall and his family. He was the owner of ICS, and a predominant sponsor of dad for over a decade, and I got on well with Stuart, Pete’s son, and David Yates and his son Jack, who was my age. I used to walk to Jack’s house, which was about a mile from Oulton Park.

When you think of all the great cars he raced, and all Dad achieved, it’s funny how he doesn’t have any memorabilia or past race cars. He’s a simple guy who doesn’t feel the need to hold onto those things and moves on.

As soon as one of Dad’s old cars comes up for sale, I will get a message from my friend Charlie Hollings, who takes a lot of pleasure in reminding me that’s the inheritance that I won’t be getting. A lot of the cars go for good money… But that’s Dad. He was running a business and the cars had to pay their way.

That sort of pragmatic approach came to bear when I was racing. As a teenager trying to race I had never seen the struggle and the journey that Dad had been on to get to where he was, which was probably counterproductive and compromising because I felt everything was going to fall into place because I was his son and he had a successful business and driving career. Not seeing those challenging years set me up for a fall, because I didn’t anticipate the challenge, and thought it would all happen naturally. Of course, it never does.

In karting, I’d always get a bollocking because I wasn’t winning. In the Renault Clio Cup it became evident that I liked to shunt! I tried to do things as quickly as possible, put pressure on myself, and made errors. I’d crash and have to rebuild the car on Monday. In my father’s single-minded style, we got about four races in and when we were back at the factory he told me it was a waste of time that it was costing a lot and he was going to sell the car. It was hard to take, especially as a teenager without a lot of direction, but it was justified and kicked me into shape.

I spent a year and a half working at a local clothes shop in Leamington Spa, which made me realise how much I missed motor racing. I managed to get some weekend work, building club-race cars with Andrew Crighton of Advent Motorsport, then I spotted an ad placed by Fortec, for a junior mechanic. Kelvin Burt introduced me to Paul Jackson, who was running the team, and that’s how I got started. They were flying high; it was a great experience that set me up for team management.

Motor sport is volatile, you need to dig deep. Dad did that, he had a determination to be successful, I suppose I have it too. I just wish he’d kept some of his cars!”