JB Millar

JB Millar has resigned his office as secretary of the Falkirk & District MC, and communications should now be addressed to RE Traill, 21 Muirhall Road, Larburt, Stirlingshire.

The look on Martin Brundle’s face the minute he walks into the garage at Silverstone is a picture. There’s an instant flicker of recognition. The same reaction as meeting an old friend.

That’s exactly what’s happening here. These two haven’t seen each other for 29 years, but today is the unexpected reunion. The moment is made even sweeter by the presence of Alex Brundle – Martin’s son and current FIA World Endurance Championship racer – who’s come along to get a feel for his father’s past. He’s getting the chance to jump into his father’s seat and relive a key moment in the family’s racing legacy.

The old friend waiting for them is the Jaguar XJR-12. It’s unquestionably one of the finest racing Jaguars ever built, and it’s a car that’s been kind to the Brundle family.

Moments after 16.00 on Sunday June 17, 1990, Martin’s dream of winning Le Mans came true with this model, but not actually this exact chassis.

Jaguar’s Le Mans success in 1988 had kick-started a fevered wave of interest among fans back home. After years of German domination, the Union Flag was flying on the top step at La Sarthe again. And for 1990 the stakes were even higher as four major manufacturers – Jaguar, Nissan, Porsche and Toyota – were vying for victory during perhaps the ultimate iteration of the power-hungry Group C era.

Brundle had started the race in XJR-12 chassis 990, the very car we have here. It was his lucky car, an evolution of XJR-9 chassis 588, the machine that had powered him to the 1988 FIA World Sports-Prototype Championship. But it’s an ironic twist that it let him down in France, and it was only a late and controversial team shuffle that saved the dream of a British driver winning Le Mans in a British car that year.

After leading for about seven hours, the big V12 of chassis 990 overheated. Its water pump had slipped a drive belt, and the number 1 car had to be retired. But Tom Walkinshaw, the driving force behind TWR and a father figure to Brundle, had a plan up his sleeve.

He deliberately kept just two drivers – Jaguar’s successful IMSA pairing, John Nielsen and Price Cobb – running back-to-back stints aboard the number 3, while third driver Eliseo Salazar sat in the garage. With more than 50,000 British fans having travelled to La Sarthe to cheer on the home-grown Jaguar team and its home-grown star Brundle, Martin was ushered straight into Salazar’s seat when his own car retired – and subsequently took the chequered flag to cement the dream result.

It might sound harsh, and it was on Salazar, who effectively walked away from sports car racing there and then, but there was logic behind it. Brundle was not only Jaguar’s fastest driver, but he was also one of the most mechanically sympathetic. With number 3 already nursing a dropped fourth gear, it made sense for Brundle to safeguard the car rather than the more erratic Salazar.

But regardless of the intra-team politics, Brundle was finally able to appreciate the words of John Wyer: “Winning at Le Mans is worth all the other world championship rounds put together.”

Brundle would return to the cockpit of an XJR, this time the 14, for a handful of races in 1991, and then he and Jaguar parted ways. Now, 29 years later, he and chassis 990 will take to the track together again.

Martin’s relationship with Jaguar’s Group C cars goes right back to the beginning, and the XJR-6. He was the first driver to get behind the wheel, during its inaugural test session, at his home circuit, Snetterton.

Over time, he’d go on to become the most successful driver in Jaguar’s Group C racers, along with Eddie Cheever. But Cheever never counted a world championship title or a Le Mans win among his successes.

Today XJR-12 990 wears its number and colour scheme from 1991, and Brundle is excited to be reunited with it. Forget the Benetton and McLaren Formula 1 offerings he’s driven since; the big cat is his favourite racing car of all time.

“I’m two months off my 60th birthday, and this is like an early birthday present!” he says, eyes twinkling and smile widening.

Brundle enthuses about the performance of the Group C racing machines. At test days, they could mix it with F1 cars. “Derek Warwick used to laugh about how he could latch onto the back of an F1 car and hassle them around the track. The F1 drivers couldn’t believe it.” Martin’s son, Alex, shakes his head in awe.

The reunion came about after I interviewed Alex, also a professional racing driver, for Motor Sport. A throwaway question, just before ending the interview, would sow the seed for this story. “Have you ever driven any of your dad’s old race cars?” I asked. Aside from a Formula 3 Ralt (Motor Sport, August 2013), Alex hadn’t tried any and said his favourite cars from his father’s era were, without question, the Group C Jaguars. The family used to own an XJR-6, but it sat in the garage, sadly neglected, and after three years of it gathering dust Martin sent the car off to a better home. “It would be my dream come true to actually drive one,” Alex told me.

The detective work began, diaries were juggled and eventually, Martin, Alex and the generous Gary Pearson, owner of the Jaguar XJR-12, were all able to be in the same place at the same time, a BRDC members’ track day, held on Silverstone’s Grand Prix Circuit.

The highlight of the occasion, Martin says as he arrives, is the chance to see Alex in the car, and find out what a modern-day sports car driver thinks of the Group C era.

The two had travelled separately to Silverstone – Martin just a day back from returning after the Chinese Grand Prix, Alex fresh from round one of the European Le Mans Series – but had spoken en route.

“To be honest,” says Alex, “I was so excited this morning, I gave Dad a ring on the way here. They [sports cars] are a lot more ‘jump in and go’ now. We have all of the electronics systems and everything. You still have to be on top of it, especially around Le Mans, but it’s different.

“I looked at the fastest time the Le Mans-winning Jaguar did, with the chicanes in place [1990 heralded the introduction of chicanes on the Mulsanne straight] and it was 3min 37sec. Last year, the fastest LMP1 car managed 3min 17sec. But it’s all about downforce now. I think in terms of power and torque the Jag’s going to be impressive.”

Sure enough, Martin recounts how it was possible to pull away from the pits, in fifth gear, by slipping the clutch. “It only had five gears, so losing one in a race was never a massive problem,” says Martin. Alex laughs: “If we do a gear now, I’d be getting a call along the lines of ‘Box! Airport!’”

“We used to laugh about hassling Formula 1 cars around the track”

Walking around the car, the enclosed rear wheel spats, low-hanging, low-drag Le Mans-spec rear wing and Silk Cut purple and white branding bring memories flooding back. Memories of rising to my feet in the grandstand before Paddock Hill Bend, at Brands Hatch, in awe of the noise of these spectacular beasts; of wandering around the paddock, breathing in the fumes of high-octane fuel and pricking your ears every time a wheel gun whirred; of leaving in the traffic after the Silverstone 1000km, in the passenger seat of my dad’s Saab 900 Turbo 16S, and chasing after one of his friends in a Ford Sierra Cosworth; of pinning Jaguar and Porsche posters, free with motor sport magazines, to our garage wall, next to my battered Zip kart.

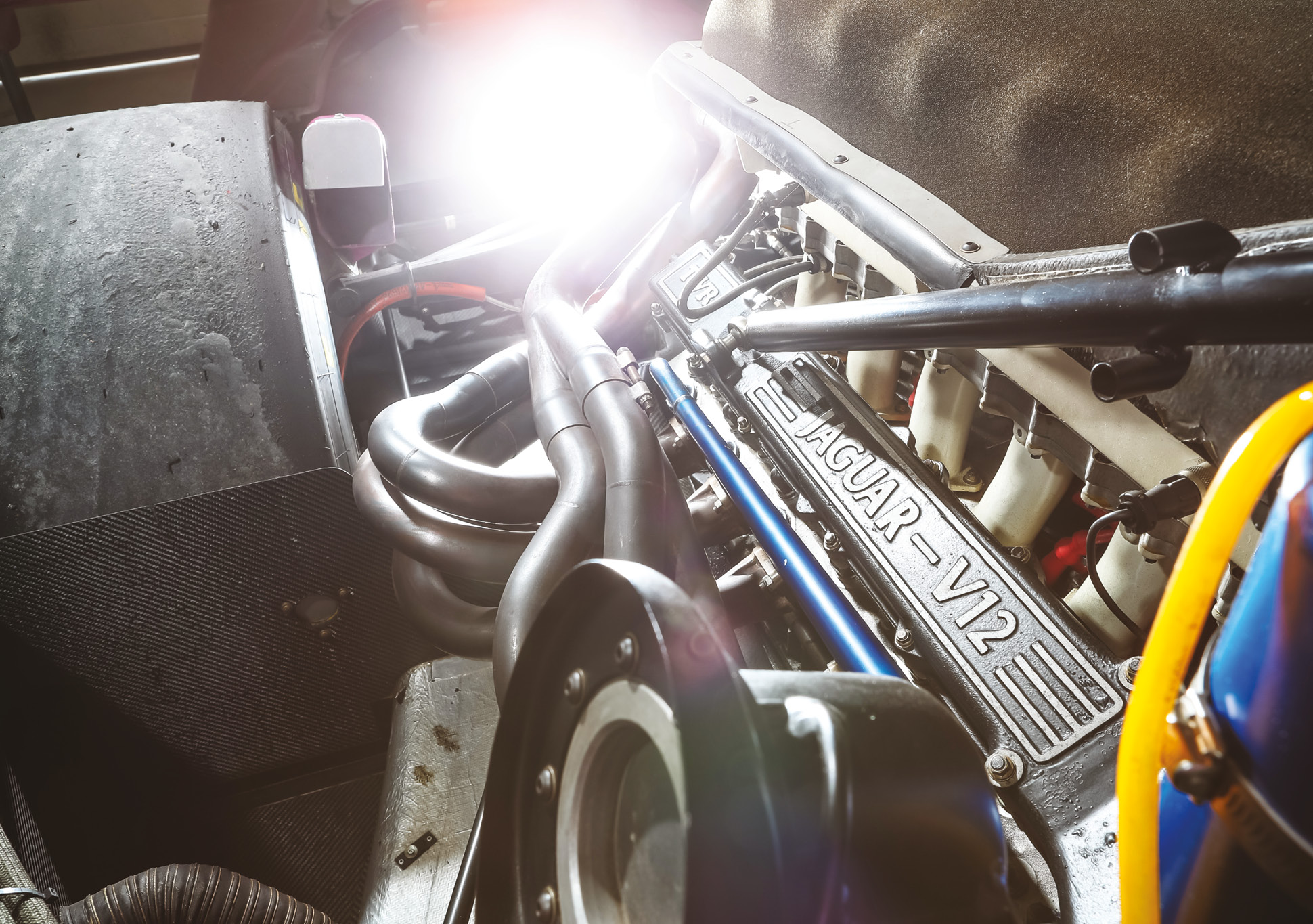

The interior of the XJR-12 looks simple by today’s standards. The suede-trimmed Momo steering wheel may be quick-release but there’s only a solitary red button, for the car-to-pit radio. Ahead is a Stack analogue rev counter, plus a pair of temperature displays for oil and water. To the left are switches for the lights, wipers and indicators, and to the right sits the exposed gearlever and linkage, the electrical master switch and a wheel to adjust the brake balance.

“I think what Alex would be shocked by is how little safety there is in the car,” says Martin, peering in. “I’d sit in the fixed seat, and would be packed, because John Nielsen was a big bloke – Super John, the Viking! – and if we were racing with Jan Lammers he’d have a great big packer, so he could see over the steering wheel and reach the pedals, because he’s a little fella. And that was it. No HANS device, no head protection. Nothing.

“If you look at it according to today’s standards, and consider a big crash, you’d think you’re guaranteed to die. Yet Win Percy had a mother and father of an accident [early in the morning, in 1987]. Down the Mulsanne he had a tyre blow. We had these sensors linked to flashing lights in the cockpit, that were meant to tell you if you had a puncture, but after five laps or so they would flash continually, so we all ignored them.

“You’d be doing 200mph on three wheels… and with no brakes”

“I used to just watch the rev counter. If the revs are down, it means you’ve got a puncture, because the tyre starts to grow and grow as it gets hotter and then goes bang. At which point, as Win suddenly found out, it takes the right-rear corner, brakes and aerodynamics with it. So now you’re doing about 220mph, because there were no chicanes back then, on a three-wheeler with no downforce and no brakes.

“I came across it and his accident went on about the best part of a mile. He walked away from that, partly thanks to the third, higher guard rail; then Win climbed over the fence because he didn’t feel very well, and they couldn’t find him.”

It’s not pure luck that Percy walked away from such a big one. Designer Tony Southgate (see sidebar) was proud of the fact the carbon tub was so strong that they couldn’t accurately measure its rigidity on existing rigs at the time. It was literally off the scale.

Percy tells a good story about what happened next. Walkinshaw was obsessed about the fact that the drivers would jump out of the car having forgotten to release the radio plug from their helmet, which would break the cable. Once Win had made his way back to the pits, he found Tom and said, “Good news! The cable’s fine. The bad news is that it’s all that’s left of the car!”

What about the stories about the weight of that 7-litre V12, and how the car’s handling was dominated by the mass behind the driver? “Yeah,” says Martin, “the V12 is a very big engine. You definitely do feel its weight. The engine’s centre of gravity is very important. I remember we tried a 48-valve head with this engine, at Brands Hatch, and although it had a load more power it proved to be slower because it altered the centre of gravity.”

The car’s aerodynamic performance was also the stuff of legend. “I think we V-maxed at about 240mph,” recalls Martin. “It’s all fine, until it’s not..! Very lazy gearing, long-legged. The Le Mans-bodied cars gather speed really quickly, because they are so slippery through the air.

“Down the Mulsanne you had the tramlines [depressions] in the road, from the trucks, and when you had to cross the crown of the road for the kink, you’d take it flat but really had to think about it, especially in the middle of the night.”

Another problem was inadvertently caused by the car’s advanced aerodynamics, designed to suck the car to the floor when cornering. If the floor wasn’t fitted exactly how it should be, the drivers would quickly know about it.

“I’d go out,” remembers Martin, “come back, and say, ‘The floor’s not right.’ You could feel it straight away, because you’d go into a corner and be like, ‘Whoa! The floor’s not right’ and the team would say, ‘The floor’s fine’ and you’d say, ‘No it isn’t’ and then they’d get under the car and be, like, ‘OK, yeah, the floor wasn’t quite right.’ As soon as it was perfectly aligned, the car would just hunker down.”

“You have this grumbly old engine until 4000rpm, and then the exhaust note just takes over”

Martin elects to drive the Jaguar first. Pearson, owner of number 35 for the past 12 years, runs it only very occasionally but has performed a crack test and fitted a new set of Goodyear Eagle slicks for today. All being well, it should be just the way Martin raced it in period.

After settling in and adjusting the straps, everything seems second-nature to him. He flicks three toggle switches, for the ignition, injectors and fuel pumps, then another for the starter motor.

The noise is something else. Martin waits patiently, revving the engine – BRAP! BRAP! BRAP! – before the signal is given to set off and follow our camera car for one lap. Running at about 50mph, the car sounds as frustrated as its driver probably feels. As I signal to pull into the pits, Martin’s finally free, and he’s gone, the V12 howling while the fat rear slicks begin searching for grip.

The crowd of onlookers grows each time he passes the pits; apparently faces are pressed up against the windows of the BRDC clubhouse, too. The V12’s exhaust crackles on the overrun into Copse, before the XJR-12 hauls away into Maggotts, its engine note carrying on the wind.

Now he’s back. And he’s a happy bunny. “Amazing! I was getting too happy and too comfortable, so I thought I’d better come in. It feels exactly like it used to, so well done Gary [Pearson]. All the mannerisms are the same. I could have been pulling out of the pit lane and joining the Silverstone 1000Kms.

“You’ve got that grumbly old engine until about 4000rpm, then the exhaust note takes over, then it gathers speed like crazy – the Le Mans-spec cars are so quick.

“It can rev to 7500rpm, but today we’re running at six and a bit, but that’s enough – we’re not trying to win a 1000k. But I tell you what, that’s plenty fast enough down the Hangar Straight. It gets up and goes.

“It’s got a good front end on it. I think Al will be pleasantly surprised. I would think what will mildly terrify him is how binary and physical it is to drive, and how much

it moves about.”

Alex is next. He fires through four laps, immediately piling on the speed and bringing a ‘that’s my boy’ smile to his old man’s face. When he rolls back down the pit lane,

we look at our watches; he’s got another 15 minutes of running time. He doesn’t need to be told twice. The fuel level is checked and off he goes.

By the time he returns, Alex has enjoyed 10 of the most memorable laps of his life. Martin looks at him, the pride welling up, then jokes that his lad looks about 12 with his helmet on. (He’s 28.)

Ever the professional racing drivers, the two set about analysing the car’s behaviour. Martin remarks on the car’s stubbornly high levels of grip at the back. “The stability is just insane,” agrees Alex. “You can just commit. It’s so tractable and just goes; through Becketts I left it in fourth, because it’s so torque-rich, so you could minimise the gearshifts and just let it get on with it. I’d say there’s more time lost changing gear than being in the wrong gear; every single shift has to be spot on.

“The steering is way lighter than I was expecting. You have a bit of bouncy bump-steer.” Martin tells him they’d learn to ignore 75 per cent of what it does.

Alex continues: “You get this feel for it, where you say, ‘The rear is fine… the rear is fine…’ and then ‘oops…’ and then you ease off and it’s fine again. In Copse, I’m knocking it down one from fifth, and you drive out, and you always know exactly where you are with the car, pushing past the understeer and finding the balance.

‘The visibility is impressive. And the braking performance is also surprisingly good, with no issues. But it always feels a bit light across the front axle.”

“The problem was always getting enough grip at the front,” agrees Martin. “But once the venturi [aerodynamic tunnel] was set up right, it would just stick. You know you’ve got a big lump behind you, but it’s not dominating, is it?”

“No, but when it’s going, it’s going. You really have to get right on top of it…”

“Because it’s a big pendulum behind you.”

“Yeah, but I can see why they would settle the rear right down for the long-distance races, and use the spool differential. Without it you couldn’t cope with it being all flighty. It was awesome. I’ve met one of my heroes.”

What insight has this given Alex into the previous generation of racers? “For drivers of dad’s era, the constant management of the car in a race means your mind must have been gone by the end. I guess, as you test and run more and more with the car, you’d understand its foibles and some of that stuff starts to become second-nature. But the constant management of the gearbox, clutch, throttle and how much driving they take is always going to be there.”

The noise of the V12 isn’t as loud as he was expecting. But a noticeable difference between the Group C Jaguar and a modern LMP car is the absence of any resonance through the chassis.

“The main issue I found was the stiff throttle pedal. If that happened now to me, in a 24-hour race, my legs would be ruined,” laughs Alex. But he’s not joking.

Martin reckons it wasn’t much lighter than that in the day: “The thing is, you’re pulling the throttle slides of 12 cylinders, and it’s got a damper on it, and I think that’s what you’re feeling. They’d only get worse as they wore, too.”

“If the throttle in my LMP car was this stiff, my legs would be ruined”

The Brundles are made up about the reunion. Martin’s wife Liz Brundle joins her boys and asks how it went. Pearson cracks a smile for the first time in the day, not because his multi-million-pound machine is back, in one piece and in full working order, but because the car hasn’t disappointed either Martin or Alex.

Spending a day in the company of this magnificent machine transports me back to an era before Instagram and smartphones with video cameras. To a time when you wouldn’t view racing through the distance of social media. You’d pack your things, get the sandwiches out of the fridge and set off at an ungodly hour to join the thousands of motor racing fans giving their undivided attention to the live spectacle of a world-class motor race.

We could pick a favourite and cheer them on. Jaguar, Porsche, Sauber-Mercedes, Peugeot, Lancia, Mazda, Nissan and Toyota; they were all there, wheel-to-wheel at speeds of up to 250mph.

To witness man and machine battling it out, for 1000kms, six, 12 or 24 hours, was humbling. There were no computers, selectable driving modes, variable traction control or telemetry. Just the driver, their skill and their stamina.

Sure, there were unsung heroes. The team bosses, like Walkinshaw, who persuaded the car makers to throw their brand into the gritty domain of Group C racing. And the engineers, like Southgate, who created cars that drivers didn’t just race, they formed a bond with. But it was the men, the pilots, and their machines, that we cheered on.

We still do. But the machines… well, let’s just say, they don’t make them like they used to.