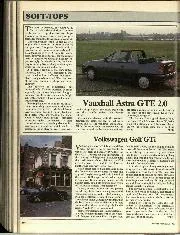

Volkswagen Golf GLi

Volkswagen's Golf GLi is to cabriolets what the GTi is to hot hatchbacks. It was as far back as February 1979 that the Golf GLS Convertible was introduced in this…

Unintended consequences invariably unfold whenever Formula 1 makes any sort of change. It’s inevitable in something so complex. They can be good or bad. The tweak to the aero regs for 2019 was done with the best of intentions, to allow the cars to run more closely together, and there probably has been a slight improvement. But some of that will also be due to the fact that the thinner gauge Pirellis – introduced to reduce blistering – do not overheat so readily when you’re close behind another car through a long corner; a positive unintended consequence of the tyre tweak.

But if there’s been a negative it’s that it seems to have impacted harder on Ferrari and Red Bull than on Mercedes. So just as those two teams seemed to be building up a head of steam, the regulation reset played against their aero concepts and gave Mercedes a further advantage.

This is to take nothing away from Mercedes; its 2019 edge will not solely be down to that. Even after five years of winning, the team has worked away with incredible focus on making the tiniest incremental changes that add up to a significant total. James Allison has mentioned that there are parts of last year’s car they believed to be at the absolute outer edges of feasibility in terms of packaging, but they already look clunky alongside the W10. This systems integration between and within the engine and chassis groups is only going to get tighter, too; an all-new digital programme running through both bases has been introduced, to make clearer to everyone the areas on which they need to focus to make the car faster. This is the most potent grand prix team of all time.

But it has been helped by the rule change. Its long-wheelbase, low-rake concept has been more adaptable than the shorter, higher-rake Ferrari and Red Bull.

The simplified front wing endplates demanded this year, with none of the complex array of turning vanes to direct the airflow around the front tyre, led Ferrari to induce the outwash around the wheels by tapering down the wing elements at the outboard ends. There is a natural limit to how much airflow you can usefully direct through the barge boards and underfloor from the inboard end of the wing; there is only so much airflow energy to be squeezed into a limited amount of space. Feed more in and you will lose more performance from the drag increase than you’ll gain from any downforce boost. So, with that area being worked to its maximum, aerodynamicists deploy the rest of it outside the wheel, where it usefully prevents the turbulence generated by the wheel from interfering with the downforce-generating flow along the body sides.

With a ban on all those endplate vanes, it’s much more difficult to turn excess pressure around the wheel. So now there is a limitation at both the inboard and outboard ends. One solution is to reduce the area of elements at the outboard end – surrendering some direct wing-generated downforce in the process – to help aid that outwash. Which is how Ferrari – and others – have ended up with that type of wing.

“We’ve had five Mercedes 1-2s at the time of writing. Not what was intended…”

The longer wheelbase of the Mercedes allows for a greater gap between front axle and sidepod and therefore the barge board area has a greater capacity. In which case there has been no need to divert so much airflow in the service of the outwash and therefore no need to surrender the element area at the outboard ends. So the bargeboards can handle a greater throughflow, creating more downforce by accelerating that part of the airflow harder, without surrendering downforce from the front wing.

Red Bull, which has traditionally favoured a shorter car, has experienced difficulty from the limitation of the under-nose guide vanes to two per side. The vanes help condition which air will be guided through the barge boards and which to the underfloor. Getting that balance right is crucial to overall aero performance. Airflow generally doesn’t like having its direction changed suddenly and has to be coaxed gently or in stages. Hence the previous multiplicity of vanes was useful to Red Bull, given that there was less length in which to change the airflow’s direction.

With Red Bull’s super-high rake concept, the negative pressure created by the Venturi formed by the angled floor helps pull the required amount of air to the underfloor, leaving the guide vanes to condition the remainder as required. But as soon as the rake decreases – when braking finishes, for example – you can find yourself with insufficient flow being pulled into the underfloor as that Venturi is no longer powerful enough. Two guide vanes may not be enough to cover the different flows required at high and low rakes. In such a situation, you probably need an even higher rake so that the floor maintains an adequate pull on that under-nose airflow even as you stop braking. But Red Bull is limited now in how much rake it can run – because the rear driveshafts cannot run at any more of an angle without putting excess strain on them and the transmission.

So we’ve had five Mercedes 1-2s at the time of writing. Not what was intended…

Since he began covering Grand Prix racing in 2000, Mark Hughes has forged a reputation as the finest Formula 1 analyst of his generation

Follow Mark on Twitter @SportmphMark