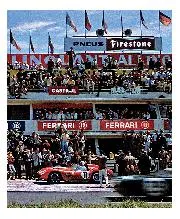

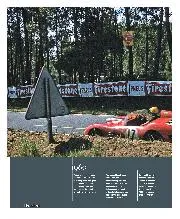

All the colour of La Sathre

Thanks to an adventurous amateur photographer, we still have a trackside view of a Le Mans which has long since vanished It's rare to see Fifties racing in colour, as…

Mattia Binotto, the man in the background doing great work at Maranello for the last 24 years, finally finds himself in the spotlight as Scuderia Ferrari’s boss. The contrast in style with his predecessor Maurizio Arrivabene could hardly be starker; quiet consensus replacing adversarial pass-it-down-the-line commands, a search for the nuances of understanding as opposed to raging against the circumstances, engineering rigour rather than marketing bluster, someone who understands how people work together rather than how they choose cigarettes.

Before his sudden and untimely death last year, Sergio Marchionne had come to realise what Binotto’s true role should be. The talents he’d demonstrated as technical director, as he’d totally revitalised Ferrari’s long-dormant creative energy, made him the logical choice to lead the whole team. The upper management left in Marchionne’s wake eventually came to the same conclusion – and so the spotlight swung around to shine upon him. Ironically, he does not enjoy that light anything like as much as his predecessor, but neither does he duck it. It’s just part of the whole, and he’s never been stressed by learning new skills or assuming more responsibility. So he sits down with Motor Sport, camera shutter clacking in the background, to tell us about his new role.

“Being technical director didn’t mean I was the best technician,” he says. “That’s not the case at all. I am the person who can help the others develop their creativity or deliver what our targets and objectives are. It’s true since I started at Ferrari I have been responsible for a continuously increasing number of people…. It’s something I enjoy, and I believe it’s my strongest skill.” He has continued with exactly the same approach in his new position.

“There are many areas with which I was not familiar until now, with merchandising, sponsors, politics, drivers. That’s the most difficult part, dealing with things that didn’t involve me in the past… but other than that, it’s just adding some people. The approach has not changed.”

Think Ross Brawn rather than Adrian Newey, then, as he expands his technical management into team leadership. He has a similar way with people, getting their respect through his actions while retaining a nicely soft exterior. The ambition and steel lie somewhere beneath, out of sight.

Changes elsewhere in the structure have barely altered with his promotion; he’s simply added another layer to his own responsibilities. So he’s pretty much in the role that Brawn inhabited back in the day, when Binotto worked in the engine department.

“I learned much from Ross. I worked closely with him and still for me he’s a good reference. Sometimes when I need to make a decision I think, ‘What would Ross do?’ He was a great leader at Ferrari. If you have such a reference you use it. There were so many fantastic people to learn from – Michael [Schumacher], Jean [Todt], Rory [Byrne]. I’m still working with Rory, of course. He is a part-time technical advisor but certainly when he’s involved he’s very passionate about what he’s doing. It’s great to have him still with us.”

Binotto’s personality has been reflected in a much more relaxed working atmosphere within the team during a race weekend, even if it’s been replaced by a different sort of tension – that of an internal competition between the two drivers.

“Rory Byrne is very passionate. It’s great to have him still with us”

Arrivabene had pressure imposed upon him by Marchionne and reacted to that by applying that pressure, in turn, to those working for him. Not in a positive way. When some development parts did not work as simulation had suggested during a critical phase of the championship, Arrivabene raged to the staff in that department: “If I get taken down, I’m bringing you all with me.” Word of that came directly from the inside. It illustrates perhaps the pressure the man was under – but also his rough, unsophisticated understanding of how to handle it, how to get the best from a group of creative people. He was essentially making exactly the mistakes that Binotto’s restructuring of the technical department had reversed for Ferrari in the summer of 2016, after years of a culture of fear.

Binotto didn’t make any big announcements to the staff upon taking over, explaining how it would be. That’s not his style. He tactfully underplays the contrast. “No, certainly the objectives are unchanged. So in that respect there was no different message. Certainly my style might be different to the past seasons, but everyone in Ferrari knows me so I don’t think it was something I needed to explain.”

He’s respected rather than feared – and that is absolutely in line with the changes he oversaw in that 2016 technical restructure, which allowed for a different, more collaborative approach that he describes as: “More horizontal – to make sure the people working for you and your collaborators are the ones responsible for what you are doing, and feel accountable. It’s really down to them to understand how we are playing our game and feeling accountable for what they are doing and it’s down to me put them in the right condition to do it.”

He gives Marchionne much of the credit for the initiative behind it, and it’s clear his relationship with the late boss was very different to Arrivabene’s.

“The real architect of that was Sergio Marchionne. He felt the necessity of changing our approach, changing things internally, giving a boost to free some energy from the entire organisation and we worked through the company looking at chassis, power unit and having one single person – myself – in the position of technical director over engine and chassis. But I did not want that to be ‘in command’; that’s not the way we approach it. I personally am fully convinced by the type of organisation in which people may feel more inclusive, feeling part of the team, feeling accountable for what they are doing, feeling accountable for what we are delivering as well. They are the people playing the game on the field, I’m simply putting them in the right conditions to deliver.”

“Sergio Marchionne was a very smart person, with a very fast brain”

Since this was implemented Ferrari has become arguably the most innovative and creative of all the teams, no longer simply adopting what other teams had done – as had become the trend since the Byrne/Brawn glory years. Suddenly it was Ferrari concepts being copied, Ferrari pushing up against the FIA boundaries of what was permitted. “I really think this is just from that change of approach,” he says. “The people have not changed. You give more freedom and you get more ideas. You remove yourself from being a bottleneck in all the decisions. It’s not one person in command, so it’s not only one person thinking. Then to make the ideas happen, what you need to put in place is just a process of escalation on certain critical decisions.

“Mr Marchionne? First of all, he was a very smart person, with a very fast brain. Very straightforward. It was easy to understand what he was asking. Very challenging – he always set very ambitious targets. But at the end of the day, for me it was a great period. I learned much. Not only from the way he was managing and approaching, also the way of thinking about discontinuity. Because what he did at the time – changing completely our approach to the organisation – was quite a big discontinuity, not only within Ferrari but in the whole of F1…

“We both strongly believed in an organisation in which everyone has their own skills and responsibilities for which they are personally accountable and this vision is shared today by our chairman John Elkann, who is always very close to the team.

“Aggressive is not the right word for Mr Marchionne. He was very demanding. Being demanding is part of the ambition. That was his way of doing it – because he was convinced that we were capable of delivering more than we believed we could.”

But it wasn’t only Binotto that Marchionne had decided to promote. The replacement of Kimi Räikkönen with Ferrari junior driver Charles Leclerc was absolutely his initiative and – as with Binotto’s promotion – something that hung in the balance for a while after Marchionne’s death. But ultimately Elkann decided to follow through with Marchionne’s plan on both. It represents ambition, even if it’s made for a dimension of difficulty that wasn’t there before as the ambitious Leclerc sees the necessity of proving himself against the veteran multiple champion Sebastian Vettel. Binotto has dealt with the inevitable flashpoints calmly, but without undermining Leclerc’s ambition or Vettel’s pride. It’s going to be a tricky situation to manage.

“I don’t think there are many tensions. Each driver is trying to do his best to be ahead of all the others, but I think we have a great understanding between us of what we are doing. The interests of the team always come first and that’s the way we are acting. Overall I am happy having Charles and Seb with us because they are fantastic drivers – and that’s a nice problem to have.”

Binotto made clear before the season started that, although the drivers are free to compete with each other, in any 50/50 situations Vettel would be favoured. “Yes, there are always situations where as a team you need to take a decision and prioritise one driver or another. In a 50/50 situation Seb has priority for the reasons I explained at the time – many years at Ferrari, four world titles, Charles still very young. That’s at the start of the season; things might evolve and we have to evaluate as it goes on. But we wanted to remove some pressure from Charles at the beginning.”

Five races in, Ferrari had twice had the fastest car but a technical failure (Bahrain) and driver errors (Vettel’s in Bahrain, Leclerc’s in Baku) allowed Mercedes to take five straight 1-2s. So what does the Scuderia need to win, to make that final step?

“No doubt the first few races have not been to our advantage. But if we look so far, including testing, we have been competitive with Mercedes except in Australia – and there were reasons we could not perform there. Even in Barcelona winter testing Mercedes was very close at the end, did the same lap as us actually. We were slightly faster in Bahrain, they were slightly faster in China. It’s the type of variance you get through a season between two cars of similar performance. It could also be that Mercedes is slightly ahead in terms of actual performance but I don’t think they are so far ahead on speed to have had 1-2s in the first five races. We are still positive, still looking with optimism to the next races. We know it will be a long season, we can see challenges. It’s what we are trying to do.

“I think we have all the ingredients to do well, but we still need to work – and work a lot. Overall we are still a very young team. And being a young team, we are in the process of learning. Even if you look at last season, towards the end of the season a few things were not perfect, shall we say, but that’s part of the process of learning. In terms of methodology, the way we approach development, we are still in a learning

phase. It’s a matter of working and building all together. I think we have everything we need in order to win. In this moment stability is key and we just need to go on working as we are.”