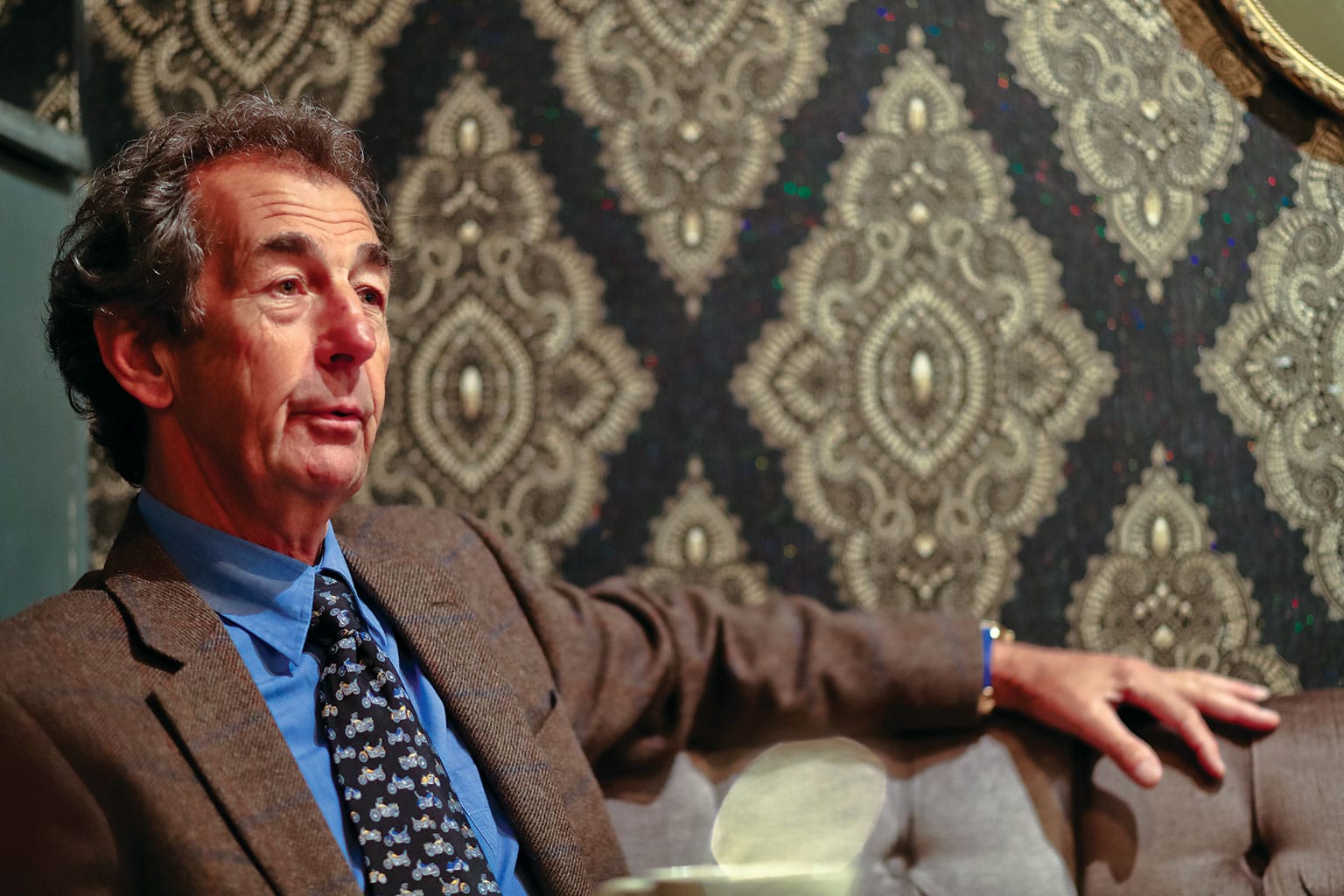

Brunch with... Steve Parrish

Serial champion on two wheels and four, media analyst… and outqualified by himself while pretending to be Barry Sheene

Lyndon McNeil

It’s a bright, breezy morning in London’s West End. Pedestrians zig-zag through Soho without looking up from their mobile phones, while cyclists with pipe-cleaner physiques maintain a casual attitude towards red lights and zebra crossings. Amid this sea of human folly, a distinctive figure strolls down Old Compton Street: slight frame, leather jacket, right arm cradling a crash helmet whose design hints that this is no ordinary commuter. Which, indeed, he isn’t.

To find out more, we adjourn to Balans Soho Society, where Steve orders black coffee, poached eggs on toast and a slice or two of bacon.

“There was absolutely no racing history in the family before I got involved,” he says, “but I seem to have been submerged in speed from a young age. I grew up on a small farm next to Steeple Warden – a disused wartime airfield. When my grandfather died he left my dad to sort out massive amounts of debt, but he managed to make enough money to repurchase the farm by breaking up the adjacent runways and selling them as hardcore that underpinned the new M1. He didn’t touch the perimeter tracks, though – and they eventually became my own little race track. It didn’t have to be a motorbike, either: it could be anything I could buy for five or 10 quid. This started when I was quite young.

“Dad sadly died from leukaemia when I was only 12 and I was left to muck around with anything I could lay my hands on. I raised money to buy stuff by washing cars, doing a bit of sugar beet-hoeing, sprout-picking or whatever. At one stage I had a 500cc Matchless that you could just get to 85mph and I’d be riding that around – jeans, no helmet, mate on the back – it was all a bit mad, really.”

His free spirit was already apparent away from his personal fiefdom. In what he believes to have been “a first for the village”, he missed his 11-plus after being expelled from primary school. “I wrote that the head teacher was fat old cow. I spelt it correctly and everything, but she didn’t like it. I was also expelled from secondary school, for more mechanical reasons: I didn’t get on with my geography teacher, Mr Carruthers, so one day removed the wheel nuts from his Triumph Herald and put the hub caps back on, which seemed quite funny when he tried to drive away. He didn’t agree, so at 15 I began an apprenticeship as an agricultural mechanic, which taught me lots of things that would later prove useful.

“Instead of playing darts or football, our village pub decided to start a racing team because two of us were thinking about having a go. My first racer took shape as a result of buying bits from Exchange & Mart: Triumph engine, Norton frame… I have a feeling the whole thing cost about £150. It was absolutely hopeless. I made my debut at Brands Hatch and the cylinder nuts all worked loose as the race went on – some of my oil is probably still there. I learned pretty quickly that I needed a better bike.

“One of the lads at the pub used to wheel and deal lawnmowers. He had more money than the rest of us and agreed to help me buy a quicker engine, I found a better frame and put together another Triton that turned out to be quite good. I started getting podium finishes in club racing in about 1973 and that set me thinking about doing it more seriously. Yamahas had arrived by then – the two-stroke era – and everyone was buying a TZ250 or 350. So that’s what I did. I saved up, borrowed £250 from my mum, acquired a TZ250, started winning a few races and never really looked back.” Quite a commitment from Mrs Parrish, that, given the period casualty rate…

Backed by chicken farmer Harold Coppock, Parrish scored good results in the UK and needed to turn professional for 1975

Motorsport Images

“I don’t think she fully approved,” he says, “but you have to remember that she knew I’d been a tearaway on the roads. I think she regarded the racetrack as a more controlled environment – you had to wear a helmet, which we didn’t on the road when I passed my test, and we were all theoretically travelling in the same direction.

“With hindsight, I could have opted for car racing just as easily as I did bikes. I think a lot of it was down to being able to ride a motorbike aged 16, a year before I could drive a car. Plus, of course, bikes were a bit cheaper and fitted in with my pub group.”

Success on that TZ250 earned him backing from chicken farmer Harold Coppock, a well-known motorcycle racing benefactor. “I started winning national-level races and getting a bit of prize money, which all went back into tyres and fuel. I was starting to realise that I must be half okay, because I was competing against established riders. For 1975 I had another sponsor, a Guildford builder called Dave Moore, and he persuaded me that it was no use winning races on smaller bikes – I needed to be on bigger machinery. He was absolutely right and generously bought me a 500cc Suzuki and a Yamaha 750. Castrol then gave me enough backing to do some proper racing in 1976. I’d long since finished my apprenticeship and had started my own little business, servicing cars and tractors, but racing now took up too much of my time and I had to pack in the day job to turn professional. My life had been consumed by the sport.”

He won that season’s ACU Solo title – and then Suzuki called.

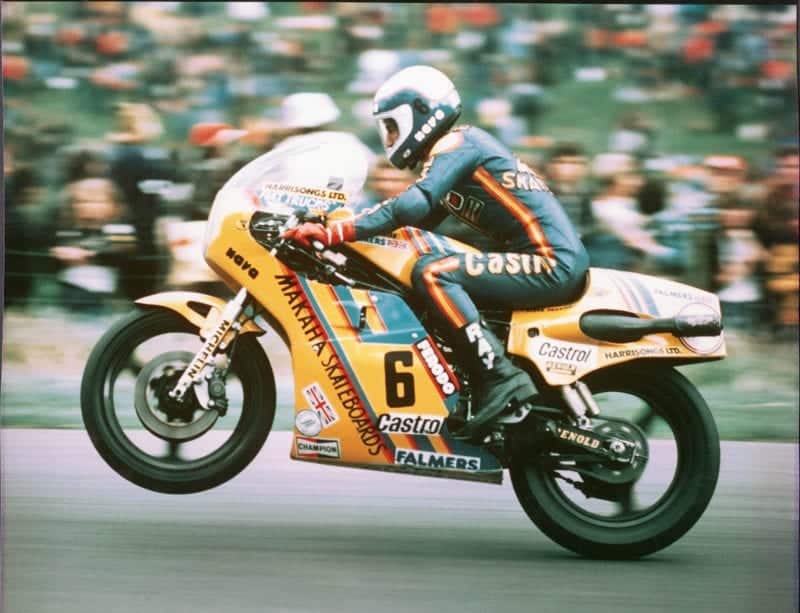

After winning the ACU solo title, Parrish joined the factory Suzuki team alongside Sheene and lost the British GP in 1977 with one lap to go

Motorsport Images

“I’d met Barry Sheene a couple of years earlier,” he says. “We lived quite close to each other and started knocking around: he was hell-bent on getting me a Suzuki seat alongside him for 1977, but to do so I had to prove I could beat his current team-mates – John Newbold and John Williams – and in all the British 500cc races I did. I loved my Suzuki RG500. I was racing against Phil Read, Barry, all the stars, and usually finished second to Barry. I probably peaked too early.

“Moving up at that stage opened my eyes to a ridiculous degree. I quite literally hadn’t sat on a plane until I flew to Venezuela for the opening Grand Prix of 1977. It was ludicrous, really. I still had pictures of Barry on my workshop wall at home, stuff I’d cut out of Motorcycle News or wherever, and now I’d been thrust into a role as his team-mate. I’d always dreamed that I might one day meet him, never mind race against him. I was as green as they come.

“My favourite moment that season was racing against Giacomo Agostini at Spa, the old, original circuit. It was one of those places where you could slipstream endlessly on the straights, passing and repassing three or four times. I remember looking across and thinking, ‘Wow! I’m passing Agostini!’ He was looking back and probably thinking, ‘Who the f**k is that?’ He’d never heard of me!

“It was an extraordinary year for me. I had a good bike – Barry’s 1976 machine, his title winner – but all the tracks were new and it wasn’t like learning circuits nowadays because most of them were so long. It was quite a steep curve. I didn’t qualify terribly well, but I raced okay and wound up fifth in the championship.”

He was also on course to end the campaign on a high, qualifying third on home soil at Silverstone and leading the race into its closing stages. “I was ahead by about three seconds when I crashed with a lap to go. I had it in the bag, but it started raining and I was first to hit the shower. John Williams had been second, but he crashed at the following corner and my team-mate Pat Hennen came through to win. Suzuki cut back in 1978 – and because of what happened at Silverstone I slipped behind Pat in the championship, so I was fired.

“Barry had broken down in that race, so returned to the pits and, just before I crashed, hung out my pit board. He’d chalked, ‘Last lap, P1, gas it – w**ker.’ Quite prescient, really, given what happened next…”

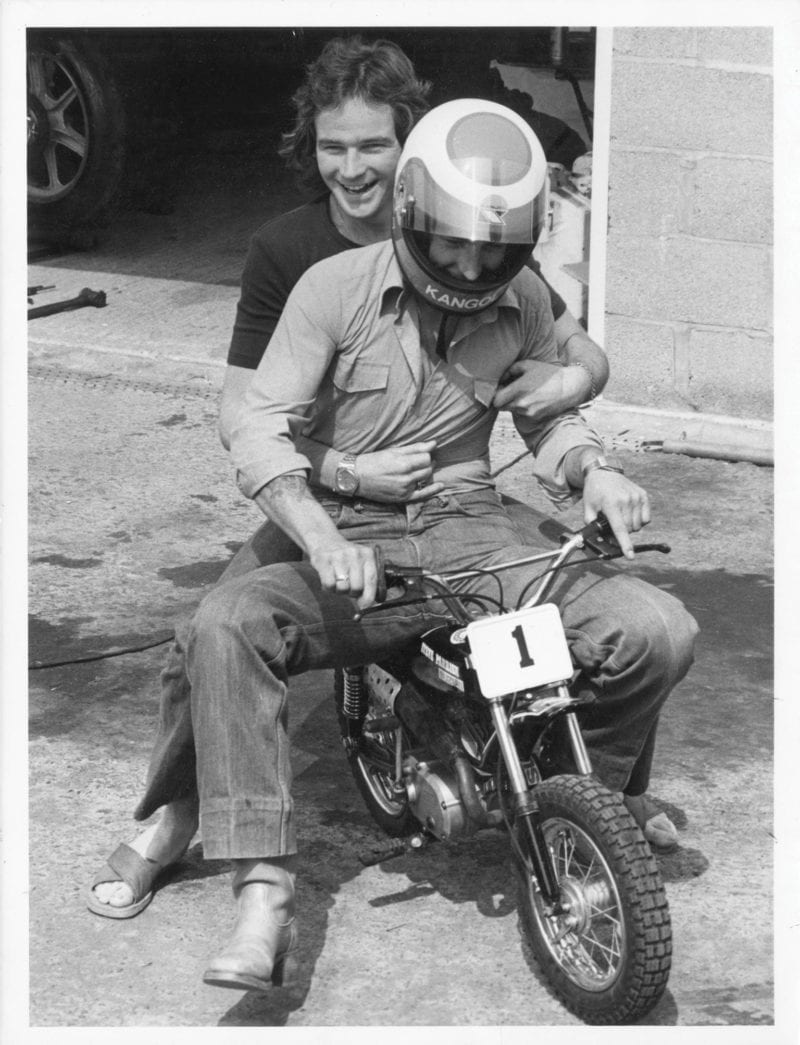

Rivals on the track, Parrish and Sheene were close mates off it. Sheene wrote the foreword to Parrish’s book in 2003

Motorsport Images

His next line is delivered in the same matter-of-fact manner he had previously used to describe earlier sponsors Coppock and Moore. “Fortunately, George Harrison stepped in with support…”

Hang on. George Harrison? Parrish laughs. “Yes, I know… Barry was very friendly with him and, as a result I got to know him in 1977. We’d be at a race and George would turn up with Eric Idle and other famous faces and I’d be thinking, ‘Jesus, how the hell did I come to be mixing with this lot?’ George was angry that Suzuki had fired me, because he didn’t think I deserved it. He helped keep me on track in 1978.”

Parrish continued to compete in the world championship, finishing fourth in Venezuela and fifth in Finland, but enjoyed greater success at home, picking up the ACU 500cc Gold Star title. “It might sound odd,” he says, “but many of us competed in multiple series back then. For one thing there were fewer Grands Prix – and for another you could earn much more in the UK. The start money in the world championship was pathetic – the equivalent of about £400 in Swiss francs. If you did international races in the UK you could earn a decent wage, but you also had to be racing in the world championship to be regarded as a worthwhile name and qualify for good appearance money. It was chicken and egg. I was getting about £2000 per meeting in Britain back then and Barry was probably on £8000 or similar.

We’d also be paid to race at places like Imola and Chimay, but at Grands Prix it was hard to earn enough to cover your costs. With the exception of guys like Kenny Roberts, who was probably being paid loads by Yamaha,most riders were travelling backwards and forwards to the UK races.”

In one instance, at Mallory Park in 1977, Parrish found himself doubling up in other ways. Is it true that he impersonated team-mate Sheene after the latter arrived with a hangover? “Yes and no,” he says. “The hangover bit simply didn’t happen. I think that rumour was started by [former racers] Carl Fogarty and Jamie Whitham, who did a theatre tour chatting about the sport, nicked some of my stories and got them wrong! The truth is that Barry turned up for free practice and a medical screw, from his 1975 Daytona accident, came loose in one of his knees and caused it to lock solid. He couldn’t ride and was smuggled out of the circuit under blankets, on the back seat of his Rolls-Royce, to get medical attention. While he was absent, I donned his leathers and helmet and went out on his bike, which I qualified on the front row. I then came in, changed back into myself and managed to put my own bike only on row three. I’m not sure that kind of thing happens nowadays, does it?”

His success in ’78 persuaded Suzuki to recruit him once again to its factory team. Hennen, the first American to win a 500cc GP, had been sidelined by a serious accident in the Isle of Man TT and would never race again. Parrish thus started 1979 alongside Sheene and Tom Herron. “It turned out to be a terrible year,” he says. “Tom was killed in the North West 200, I broke my wrist in Venezuela, the opening race, and Barry contracted a debilitating virus that slowed him down.” With a best result of fifth to his name, in Sweden, he was promptly fired once more. “Given my track record at school,” he says, “I was fairly used to such things by then…”

He would carry on competing at world level as a privateer, without ever scaling the heights he reached at home. He won the 1979 Shellsport 500c title – “My proudest achievement on two wheels, because I was competing against Barry and beat him” – and continued to chalk up wins at home. In the 1982 French GP at Nogaro, he finally recorded his first podium finish at world championship level – albeit in a race that many factory riders boycotted because of concerns about track conditions. Not untypical, perhaps, for a rider who graduated to Grands Prix just after the world championship had turned its back on the Isle of Man, but continued to race there all the same. He made his debut on the island in 1974 – finishing seventh in the Lightweight TT – and continued to enter long after other leading riders had chosen to stay away, taking a best result of fourth in the 1984 Production TT. He also raced at Macau, Chimay and other venues of a particularly perilous persuasion. How did he balance the equation of reward versus potential risk?

Dropped after one season as a works Suzuki rider, Parrish won the ACU Gold Star title in Britain, and promptly got his old job back

Motorsport Images

“Quite simple,” he says. “I really didn’t want to die. I was seriously within my limits when I raced. I know I fell off like the rest of them, and I was maybe lucky on occasions to hit a straw bale rather than a lamppost or a tree, but I was never a brave racer. I think I had natural ability and the intelligence to make sure I had a good mechanic, a good bike, the right tyres and so on, but I was never gung-ho. I didn’t see red mist when I raced. I kind of worked out that, ‘Yeah, third place will probably do.’ I really had no interest in waking up in strange hospitals with broken legs and arms. I was quite pragmatic. Perhaps that’s why car racing might have suited me better – I didn’t like pain and was allergic to it from an early stage.

“Also, I never had the attitude that I was going to win. Talk to someone like Carl Fogarty and he always absolutely believed that, but I preferred the pessimistic approach – an optimist with experience, if you like. Even when I was racing trucks and dominating, I’d go in thinking, ‘A podium will do today.’ Had I gone in expecting to win and come away third, I’d have been distraught. It was a sort of reverse psychology. Nowadays MotoGP riders have dieticians, psychiatrists, fitness trainers and all sorts. All we had to do was sober up in time for Saturday morning and get on with it. If I lacked anything it was probably a little self-confidence. If you have ability, determination, fire in your belly, character and complete self-confidence, then wrap it all up, you get a Rossi, a Márquez or a Sheene.”

It’s not unknown for top-line riders to dabble with four wheels – and by 1985 Sheene was racing for Toyota in the British Saloon Car Championship – but Parrish’s next step took him into altogether more substantial territory.

“When I started racing in Grands Prix,” he says, “all I saw was that ribbon of asphalt and the chequered flag. In about 1983 I started to notice the barriers that came with that ribbon and a couple of seasons later I started to notice the ambulances that were parked beyond. That’s when the throttle no longer stays open, even when you think it does. It was probably more the case then than it is now because the penalty was often greater than the crime. You were far more likely to die, whereas MotoGP riders now they have airbag suits, back protectors, foam barriers and so on. In my day there were generally three or four fatalities a year and it was just accepted. That was my inbuilt fuse: too many people were being killed, and that’s what slowed me down.

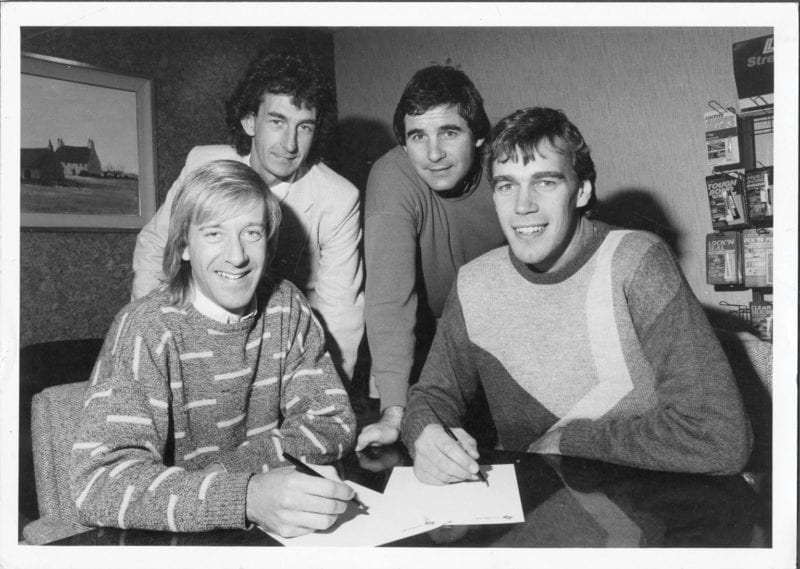

“So I was aware that I wasn’t getting any faster on a bike, I was sick of hurting myself, had a family on the way and a really good sponsorship deal with Loctite. They wanted to continue, so I retired from riding at the end of 1986 and set up my own team, with backing from them and riders such as Terry Rymer and Rob McElnea. We had a lot of success, winning four titles and a couple of World Superbike Championship rounds between 1987 and 1991, and that might have continued had truck racing not turned up.

“My first such event had been in 1984, the very first UK truck race at Donington Park. Barry was signed to drive for DAF, through one of his bike racing connections, Martin Brundle was in a Renault, Barry Lee and Willie Green were there along with drivers from many different spheres of car racing. It turned out to be a crazy event – they claimed there were about 130,000 people present and I can believe it. The roads all around were at a standstill and I think East Midlands Airport had to be closed for a while because emergency vehicles would not have been able to get in or out.

Parrish wangled a deal to race a Mercedes at the UK’s first truck meeting in 1984, something that led to bigger, better things

Motorsport Images

“I was disappointed not to be invited initially, but managed to do a deal to get hold of a Mercedes. They brought it along for me to try and suggested I try it first on the road – they were all road trucks. I’d never driven anything bigger than a Ford Transit, but pretended I had the correct licence and then drove off, crunching gears and telling them it was because I was more used to a Scania. But by the time the race came around I was as quick as anybody and it built from there.

Racing a five-ton truck is honestly quite similar to racing a bike. A single-seater car is very responsive – you can jink it, turn and it will go where you point it. A motorcycle isn’t like that. You can’t swerve on a bike, you have to coax it – and a truck is the same, with all that kinetic energy. You had to coax it because it didn’t want to go where you wanted it to go, so you needed to be gentle – and that helped early on. I felt absolutely at home.

“At first I’d just do occasional races in the UK, supported a little by Mercedes, but I won the British title in 1987 and at the end of 1989 Mercedes invited me to test with the factory’s European championship team at Hockenheim. I was about a second quicker than the regular drivers, so they offered me a contract there and then – a good deal, similar to the kind of thing their DTM drivers were on.

“During my last couple of years as a team owner I was having to duck and dive between management duties and racing trucks. It came to a head late in 1991, when Yamaha and Mercedes both decided that something had to give. It was a fairly easy choice, because I knew I could go back to running a team when I was 60 but wouldn’t be able to drive professionally at that age, so racing got the nod.”

A fruitful choice, as it transpired. He won a European title at his first attempt in 1990, adding a second British crown for good measure, and by 1996 he had accumulated five of each. He would continue as a Mercedes driver until the end of 2001, his career on four wheels lasting slightly longer than that on two, and remained a front-runner to the end.

“I did it for more than 10 years and went to hospital once, as opposed to 40 or 50 times when I was racing bikes,” he says. “A lot of car guys came in and did okay. Towards the end I was probably getting a bit slower and some of the younger guys started getting the hang of it. All of a sudden, drivers who were struggling to make any money from car racing worked out that they could do okay in trucks.

Parrish as team manager, with Keith Huewen (left), Trevor Nation (right) and sponsor Loctite’s managing director Geoff Bennett

Motorsport Images

“It was a good place for companies like Pi to develop electronic systems that could be adapted for cars, because there was space for these huge great boxes – and once they’d made it work they could start shrinking it down. At one point my data-logging system took up about half the cab. We had independent braking systems, electronic diffs… and an immensely powerful 12-litre V6. We’d test alongside the DTM cars at Hockenheim and be able to outdrag them to 100mph, when the speed limiter kicked in. We did some tests for a TV show and my truck was quicker from 0-100-0 than a Porsche 911 Turbo.

“My decision to stop at the end of 2001 was quite straightforward. Mercedes-Benz withdrew from the sport – and that sparked a decline in the whole business, because MAN didn’t see the point in continuing without Mercedes, and then DAF did the same. It would be like Ferrari pulling out of F1. Also, by that stage I’d taken up commentary roles with the BBC and others and the Beeb gave me a bit of an ultimatum: they wanted me to commit more fully to broadcasting… and that coincided with Mercedes’ withdrawal. Talk about lucky…”

He would spend more than a decade with the BBC, UNTIL IT lost its MotoGP contract, but still does bits and pieces of media work for the Beeb, Eurosport and others. “I still watch MotoGP when I can and it continues to fascinate me. Everyone seems to hate Marc Márquez, but he’s the best of this generation. The biggest sadness I have as a pundit – and a fan – is that I never got to see Casey Stoner and Márquez race together. In the time I’ve watched and commentated I think they are the two quickest guys I’ve seen.” For a while he held a world record for achieving the fastest speed ever recorded in reverse – “I believe it was 89mph, in a Caterham at Bruntingthorpe. Nobody else fancied doing it, but if anything went wrong I reckoned the worst that could happen was that I’d end up going forwards.”

He also serves as an expert witness during motorcycle racing accident investigations, hosts theatre tours, is an ambassador for Avon Tyres and conducts work for motorcycle manufacturers Indian and Triumph, – “all sorts of things that keep me away from a proper job” – and still races classic bikes for fun. “That sounds like it’s for a bunch of old fools, but most of the riders are about 25 – they just happen to be on older machinery. I’m down to do some enduros on a Suzuki Katana, built by Suzuki UK to help promote sale of vintage parts – a lucrative new market for manufacturers. I think it’s a 1989-90 model, with 150-odd horsepower – a pretty handy machine when you consider that the fastest bike I raced in period would have been a Yamaha TZ750 with 130bhp. It will be better than anything from my era in terms of brakes and tyres and, in all probability, it won’t seize, unlike some of my old stuff.”

On top of all that he has also just written a book, Parrish Times. “It’s not so much why I’ve chosen to do it now,” he says, “as why I didn’t do it earlier. I always made notes when I was racing and it has been in the planning for quite some time: Barry wrote the foreword for me… and he sadly passed away in 2003, which rather underlines how long it has taken.

“Racing brought me so much fun and the book is about that – an age when you could have an enjoyable life and still race professionally. I don’t think anybody else will be able to tell a story quite like it, unless they are even older than I am. My racing punctuates it, but if I’m honest I wasn’t good enough to write a book about my own career. I was, though, very good at getting into trouble and then getting out of it again, so it is more about that.”

On which note, is he still banned from attending the Macau GP?

“No,” he says. “That happened after 1985 and remained in force while the colony was under Portuguese control, but ended when China reclaimed sovereignty at the end of 1999. I have been back since.

“It was a result of four of us letting off a firework inside a brothel – and it was probably bigger and better than we’d anticipated. A senior police official was actually in there at the time and one of his colleagues was in the bar at the front: we flung this thing in and didn’t get away because we were laughing so much, not least because it turned out that we knew many of the people who came running out through the haze… The police came to our hotel that night and confiscated the passports of those they held responsible, though I actually had two with me.

“When everyone was due to return home the following morning, the police arrived and we assumed they were returning our passports… but they had actually come to arrest us. We were all in the foyer and I realised what was happening, so took a lift to the first floor, exited via a fire escape, took a cab to the hydrofoil and got on one just before it left. I reached Hong Kong and was sitting having a gin and tonic when the rest of the party caught up. I was feeling very pleased with myself until I was told that the police had impounded all the F3 teams’ cars and all the motorbikes and wouldn’t release any of them until I returned. I had no choice, really. I wish I’d had a camera phone back then, because the police had blown up the picture from my passport and there was by now a poster at the hydrofoil terminal in Macau: ‘Wanted. Do not let this bloke out,’ even though I’d already gone and was now coming back in. We spent four days in prison and I had to phone my new wife to explain that I’d been arrested for blowing up a brothel, which wasn’t too well received.

“I like to think I’ve had an interesting life – and I’m certainly not going to die young because I’m already too old for that.”

Steve Parrish career in brief

Born: 24/02/53, Cambridge, UK

1972-1975 Club and national racing in the UK 1974 IoM TT debut; 7th in Lightweight race, Yamaha 1976 ACU British solo champion, Suzuki 500 & Yamaha 750 1977 500cc world championship, Suzuki; 5th 1978 ACU Gold Star champion, Suzuki 1979 Shellsport British champion, Suzuki 1982 3rd in French GP, Yamaha 1984 4th in Production TT, Yamaha; truck racing debut, Mercedes 1986 retires from bike racing 1987-1991 runs Team Loctite in British Superbike Championship 1987-2001 Truck racing, Mercedes; 5 British titles (1987-1993) and 5 European titles (1990-1996) 2002-date Assorted media and ambassadorial activities to stave off the need for “a proper job”