A month after the Watkins Glen success Uncle Sam intervened with the arrival of Hurley’s draft papers. “Soon I was on a plane to Vietnam. I was stationed 100 miles south of Hanoi, and my senior officer knew I was into racing. About 20 years later a guy came up to me at a race in Atlanta and said. ‘I bet you don’t know who I am.’ I said, ‘I know exactly who you are…’

“When you go into a combat theatre you have to grow up in a big hurry. I went out as a 21-year-old kid and I came back having learned the protocol of when and where to do what, and how to be very efficient with my time and my energies. There had been a lot of lessons that I would use in racing. After that it was just listening to Peter, taking his advice, and practising what he was famous for, which was perfection. He was known as Peter Perfect. Everything had to be right, everything had to be immaculate, everything had to be ready for any eventuality. Nothing was taken for granted.

“From the start he’d established the Brumos team colours – white with two broad stripes, one red, one blue – and the shades of the red and blue paint had to be a very specific colour code. The cars were brought to the track in the biggest hauler in the paddock, immaculate in the team colours of course. All his mechanics wore spotless matching uniforms, at a time when nobody did stuff like that. And the Brumos cars almost invariably ran as number 59. Back when Peter was in naval intelligence he was flying a fixed-wing aircraft over an aircraft carrier one day, and the number on the front of it was 59. He decided he liked the way the numbers hung together, so that’s what had to be on his cars.

“Peter was very short on compliments: he expected excellence from everyone as a matter of course. And if you didn’t perform to his standards you were in the shithouse.” The team motto was hung on the race shop wall: kein Vergleich – literally, no comparison. For Peter, Brumos had to be in a different league.

Haywood and Gregg finished 29th in the 1971 Daytona 24 Hours in this Porsche 914/6

It was 1971 before Hurley was home from Vietnam, and at once there was a job for him at Brumos. “I was put through the wringer: workshop, parts, showroom. And I was racing with Peter. He was now running the Porsche 914/6 GT, because the 914 was what Joe Hoppen [Porsche North America’s Motorsport director] wanted to promote at that time. Peter and I had a lot of success with it and were IMSA champions, and the next season I was IMSA champion again with a 911. In 1973 we had the 911RS, which evolved into the RSR, and things really started to go well.” Sensationally the Haywood/Gregg 911 beat all the big works cars to win the Daytona 24 Hours outright. Seven weeks later they repeated the feat in the Sebring 12 Hours.

Hurley’s reputation in the USA was mushrooming, and Vasek Polak, who had bought one of the fearsome 917/10 Porsches for the Can-Am Series, signed Hurley to drive it. “Peter was always happy to release me to other people, because he encouraged you to drive anything you could, get outside your comfort zone, learn about the strong and weak points of different cars and different teams. So I drove a Ferrari Daytona at Sebring, I drove one of Tony di Lorenzo’s Corvettes which was crude and very fast and I later I drove a Ferrari F40 for somebody. Horrible thing, it would always blow up or something would break, not Porsche philosophy at all. The only plus point was the team used to serve great food.

“With that 917/10 Can-Am car I went from 300bhp with the 911 to 1200bhp. It was a monster, very difficult to control. At Edmonton in the wet I had brake failure, went over the bank and upside down. If it hadn’t been for Mark Donohue I would never have been able to get my hands around that car. Mark, driving for Roger Penske, had the longer-wheelbase 917/30 that was easier to handle, but he helped me a lot with sorting out the 917/10. He and I became close friends.

“In 1976 Peter fell out with Porsche over money. He was a businessman and he’d won them Daytona, Sebring and plenty else, and he’d done a lot for the standing of Porsche in North America. He said, ‘If you won’t give me what I want I’m going to run with BMW.’ They never thought he’d do it, but he did: so we had a one-year deal racing the 3.0 CSL, which was a great car, and Brumos also became a BMW dealer. But not for long: after his year racing with them Peter hated them, didn’t find them nice to deal with. Meanwhile I carried on driving Porsches for other teams, like Vasek Polak’s 934 in the Trans-Am.

“In 1977 I scored my third Daytona 24 Hours win in five years. After that Jo Hoppen told me, ‘You need to call Stuttgart. They want you to drive for them at Le Mans.’ Well, I had to pick myself up off the floor. I’d read about Le Mans, I’d seen the McQueen movie, but I’d never done a race outside North America, I’d never even been to Europe. So I fly to Paris, land the Tuesday before the race, hire a car at the airport, get completely lost getting out of Paris. Somehow I make my way in the general direction of Le Mans, but of course I don’t speak a word of French, and all I have is a piece of paper with the name of a village where the Porsche team hotel is.

Another Daytona win in 1977 with the RSR

ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images

“It’s the middle of the night, and I’ve no idea where I’m going. Then, driving along this silent country lane, my headlights pick up a guy walking along in the dark with Porsche written on the back of his jacket. I stop and wave my piece of paper at him, and he says, ‘Ah, Herr Haywood, we are waiting for you. Come and meet the boys.’

“It was race engineer Klaus Bischof, and he took me to this bar. I hadn’t slept since leaving Florida two days before, and they got me completely plastered. Klaus got me to bed at 2am. Next morning I’m woken by this banging on the window, and it’s the Porsche media chief, Manfred Jankte, saying in excellent English: ‘Where the f*** have you been?’ That was my introduction to being a works driver for Porsche.

“We go to another village, Teloché, where Porsche has taken over the local garage to prepare the cars. Back then the teams weren’t based in the paddock, they were scattered around in different villages, and all the race cars were driven on the road to the track each day. We walk into this little workshop and there are the most beautiful cars I’ve ever laid eyes on: a pair of white Porsche 936s, with the red and blue stripes of Martini running from headlights to tail. There was my co-driver, Jürgen Barth, whom I’d never met: he was a lot bigger than me, but we managed to sort the seat out OK. In the other car were Jacky Ickx and Henri Pescarolo. Jacky was like a god to me, I was just this young brat.”

Porsche 936s being prepared in a rented garage ahead of the 1977 Le Mans 24 Hours

Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Wednesday’s qualifying was torrentially wet, but it was dry for Thursday evening. Ickx in Porsche No3 qualified third among the very fast Renaults, Hurley and Barth qualified seventh. “After that they say to me, ‘Haywood, you will drive the car from the start.’

“So the race starts, we take off, this huge traffic jam of 55 cars rushes under the Dunlop Bridge and down the other side – and my throttle jams wide open. Oh shit. There was a little bar to kill the engine, so I hit that, try to keep out of everybody’s way, and I get it stopped on the verge coming out of Arnage. I get the rear bodywork off, get the throttle unstuck, get the body back on, drive it back to the pits. That was fixed and away we went, now a lap and a half behind everybody else.”

After a couple of hours the Haywood/Barth Porsche lost more time – a fat 24 minutes – to replace a broken injector pump. Gradually they moved back up the order: and then just before 8pm Pescarolo blew the engine in the No1 936. “That’s when they said, ‘OK, Jacky will drive with you guys now.’

“Jacky was brilliant at night, especially when it rained around dawn and the conditions were horrible, and he maintained amazing pace. Gradually we climbed up the field, and by 10am on Sunday we were in the lead.” From then on Ickx stood down, and Hurley and Barth reeled off the final hours. Right at the end the car suffered a major engine malady, but Barth was able to limp to the chequered flag. Ickx had won his fourth Le Mans, and his third on the trot; Hurley had won Le Mans at his first attempt.

Hurley drove Porsches at Le Mans for the next six years, finishing on the podium three times: two thirds, and then in 1983 another victory with Vern Schuppan and countryman Al Holbert. There had also been two more Daytona 24 Hours wins. But meanwhile there had been cataclysmic changes at Brumos.

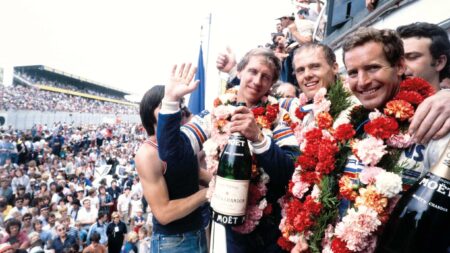

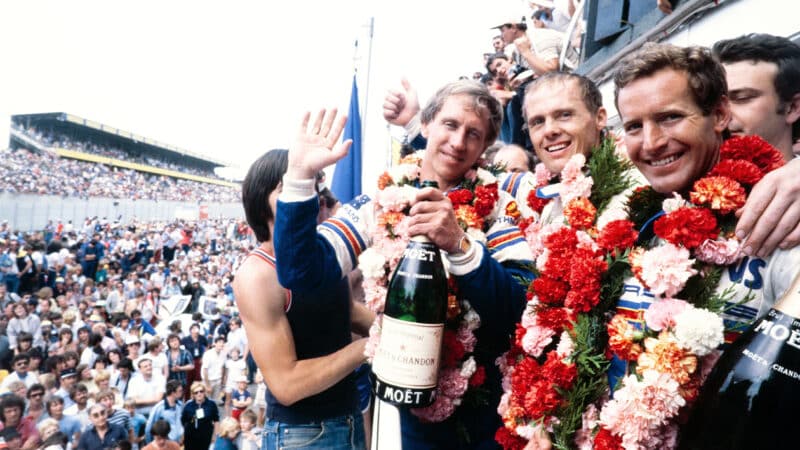

Victorious 1977 Le Mans debut in Porsche 936 with Ickx and Barth

Getty Images

Peter Gregg’s relentless hunt for perfection could not hide, and in fact was evidence of, his very complex character. “Peter had a multitude of problems. He was a manic-depressive, and mental health issues of that sort were much less well understood then than they are now. He was married to Jennifer, who was part of the Johnson & Johnson medical supplies family, and they had two sons. But that marriage eventually failed. His personality swings made him like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. He was a Harvard graduate and a naval officer, and he could be a dreadful snob: sometimes, if you didn’t have the right education and the right money, he’d treat you like shit. Another day he’d befriend some down-and-out in the street and say, ‘You and I have a lot in common. Let’s sit down and talk about it.’ One day he’d tell me what a great guy I was, the next he’d throw me out of his office. But our relationship carried on working because I accepted all this. I knew that was Peter.

“Something which must have been tied up in his torment was the terrible thing that had happened in his childhood. On his seventh birthday his mother went out to buy him a birthday cake. Coming home on the subway she carefully put the cake down on the platform and jumped in front of a train.

“Peter lived inside a sort of cloak. As long as he took his medication he was fine. But he was so clever, so highly educated, that at times he’d decide he was strong enough and smart enough not to have to be managed by medicine. When that happened you never knew which direction he’d go.”