The Monza had been unable to beat Bugatti and Maserati, while the Tipo A twin had proved both obese and a clenching challenge for even Alfa’s finest stars to drive. The AIACR recognised GP races of not less than five hours and not more than 10 – and while the fastest car in the 1932 Italian GP was Fagioli’s Maserati V16, the winner was the svelte, slender new Tipo B with Nuvolari aboard. Three of these new Alfas dominated the French GP at Reims, and followed up with Rudi Caracciola – released from Mercedes-Benz as a cost-saving measure – winning the German GP. He then triumphed in the Italian GP at Monza, while Bugatti found consolation as the Tipo Bs broke in the Monza GP, won by Chiron’s T51.

Alfa Romeo’s great results through 1932 facilitated the State-backed – more or less bankrupt – company’s shock decision to retire from racing for 1933. Its state-of-the-art Tipo Bs were consigned to storage, leaving the quasi-works Scuderia Ferrari to make the most of its dual-purpose Grand Prix/sports-racing Monza models.

German economic austerity led to the national GP being cancelled, Nuvolari deserted Scuderia Ferrari in disgust at the inadequacy of its Alfas and, in a freshly purchased Maserati 8C Monoposto (reintroducing hydraulic brakes to the GP category), won the Belgian GP. At Livorno he beat Brivio’s SF-entered Monza by eight minutes and shamed Alfa’s board – nudged by Mussolini’s unimpressed Ministry men – into releasing its Tipo Bs to the Scuderia.

Bugatti launched its Type 59, which looked outmoded and had little hope of combating state-assisted Italian programmes.

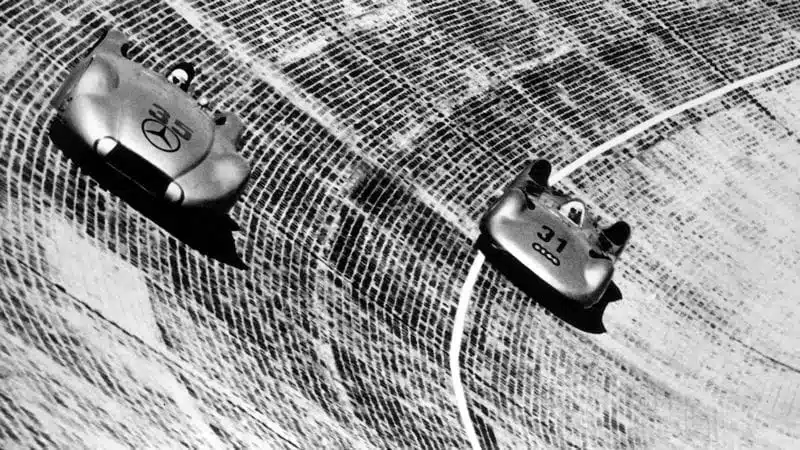

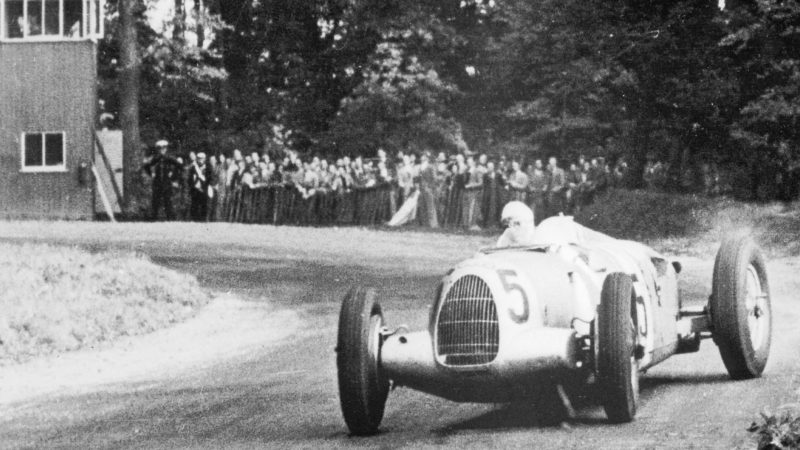

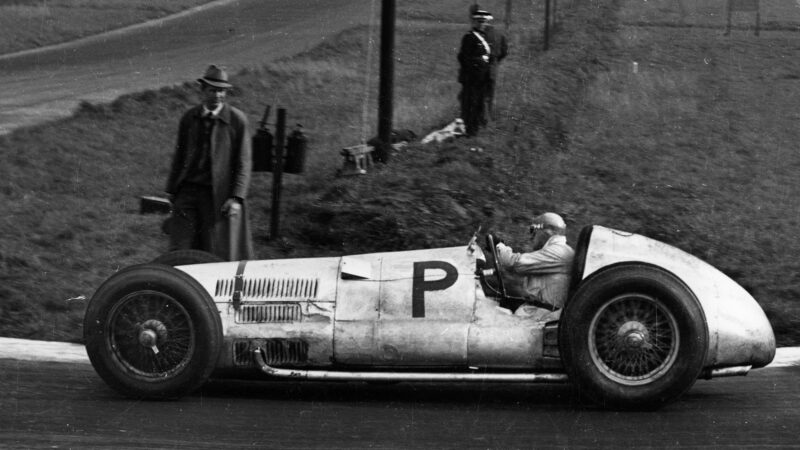

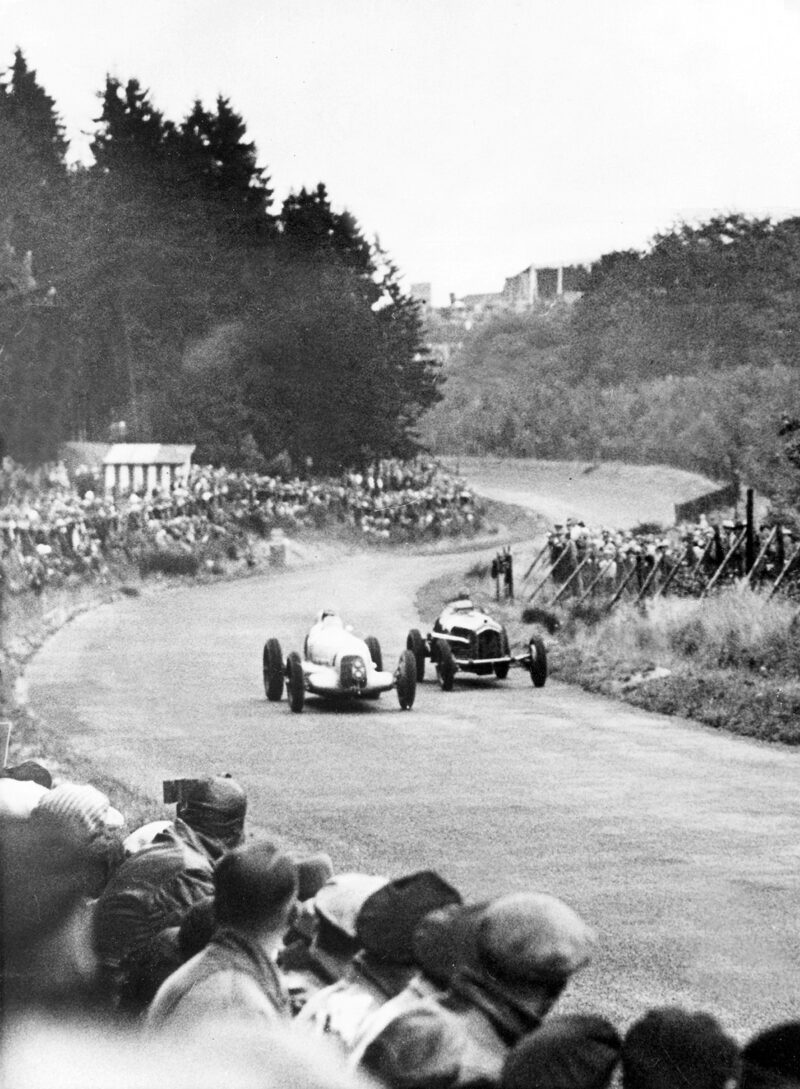

Vittorio Jano’s P3 was a revelation in 1932 but by the 1935 German GP, above, Auto Union and Mercedes had gained the upper hand

Simultaneously, the Alfa and Maserati men listened aghast to rumours that the Germans would be weighing in come 1934. Despite all its terrible times post-WWI, the German economy was resurgent and the nation’s new Fascist regime had much more muscle than Mussolini’s Italy could ever flex…

North of the Alps, Mercedes-Benz had been founded upon clinical engineering excellence. The marque had been promoted assiduously through many years of motor racing, and whenever Mercedes addressed its ambitions seriously in any class of competition, its will and capability had proved almost irresistible.

In 1931 the AIACR had canvassed expert advice to frame at last an acceptable, workable new Grand Prix formula. When finally announced in October 1932 – to apply during 1934-36 – they introduced a maximum weight limit of 750kg to be enforced less driver, fuel, oil and tyres, and a minimum body cross-section at the driving seat of 85x25cm, or 33.5×9.9in.