Lunch With... Motor Sport

In our 90th birthday issue we depart from routine to reminisce with some of the people who have kept the title alive

James Mitchell

The remarkable event that we celebrate in this issue – the fact that Motor Sport, after 90 years of publication, has not only survived, but continues to flourish – is almost without equal in the world of car magazines. In the English language (and surely in any language, unless someone can correct me) only the weekly title Autocar, which concentrates on the modern road-car world, has been alive for longer. And our longevity has been despite, or maybe because of, an eccentric history that has rarely had much to do with the commercial realities of magazine publishing. In fact, eccentricity is the word that springs to mind when describing the three people to whom that survival is primarily owed.

The story of Bill Boddy editing the magazine for more than half a century, mainly by post from his rambling, leaky old house in North Wales, is well-known. So is that of Denis Jenkinson, the bearded, opinionated little Grand Prix reporter, whose fearless and highly detailed reports were for some 40 years the accepted authority in F1. Much less well-known, at least by those who never penetrated the dark, dingy Motor Sport offices in London EC2, was the third eccentric: the proprietor, Wesley Tee. This dictatorial, erratic individual took over the magazine in 1936 in lieu of unpaid print bills, and ruled it with a parsimonious rod of iron for 60 years, refusing to entertain ever-rising takeover offers from big publishing companies until his death, aged 91, in 1996.

Whenever people who have actually worked on Motor Sport down the years run into one another, the result is always a stream of hilarious do-you-remember anecdotes that serve only to underline how unlikely the whole operation was. And always the stories are centred around the same three people, known universally as the Bod, Jenks and the Old Man. So it seemed a good idea for my Lunch With… this month to gather together five key individuals who have played their own part in the magazine’s history, and experienced many of those stories first-hand.

We meet for red pepper soup and haddock pie in The Ram, Motor Sport’s local just across the road from the converted riverside warehouse in Chelsea that is its home today: Wesley Tee’s eldest son Michael, for many years the magazine’s photographer, as well as production manager and buffer between his father and the rest of the staff; Clive Richardson, assistant editor for 10 years in the 1970s; Gordon Cruickshank, who replaced Clive in 1982 and today, after a term longer than all except The Bod’s and Jenks’, is still here as deputy editor; Simon Arron, actually the first person to be called editor after Boddy in 1991 and now back on the magazine as features editor; and Damien Smith, in his second term as editor and the man ultimately responsible for the quality, variety and depth of today’s Motor Sport as it enters its tenth decade.

For the last 20 years of his life Bill Boddy was called founding editor of Motor Sport, but that was actually a courtesy title. It was a small-time publisher and advertising agent called Radclyffe who decided 90 years ago – for some reason lost in the mists of time – that what the world needed was a monthly magazine about motor racing. When it was launched from a little office in London’s Victoria in July 1924 it was called The Brooklands Gazette; but, as it also covered the sport outside the confines of the Weybridge track, its title was changed a year later to Motor Sport. Radclyffe didn’t persevere with it for long, and during its first five shaky years it had at least five editors and owner-editors, one of whom lasted only a month. In 1929 it nearly disappeared altogether, only to be rescued by a rich young amateur racing driver named Tom Moore, who kept it afloat for a while and even sometimes edited it himself. Then Moore’s attention was diverted by a glamorous actress, whom he pursued to America and subsequently married.

Motor sport’s current offices enjoy a view of the Thames

While he was gone the print bills went unpaid, and in 1936 the managing director of the printer, one Wesley Tee, came after his money. What he found was a struggling little magazine with effectively no assets at all. But piled up in the cellar were the old photographic blocks of the pictures that had been used month by month in each issue. In those letterpress days the blocks were made of copper, which had considerable value. Michael Tee takes up the tale:

“The story was that my father took over the magazine to pay the debts he was owed. In fact he paid £20 for the publishing rights, and then sold off the copper blocks for many times that. So, typically, the Old Man did all right out of it.” Now Wesley Tee was no longer just a printer: he was a publisher too – even though he had no interest whatever in motor racing or the car world.

In Tom Moore’s absence the editor was a man called Mason, who found that the easiest way to get the job done was to delegate all the writing to an unemployed youngster called Bill Boddy. This lad had been bombarding the magazine with articles and letters since his early teens, drawing on his already voluminous knowledge to correct errors. Rodney Walkerley, assistant editor in those days, said: “Whenever that schoolboy appeared I used to hide in the lavatory.” In 1930 Boddy, now all of 17, began contributing to Motor Sport regularly. Mason, who wanted an easy life, found that this young lad was happy to churn out copy for 10s 6d (52.5p) per 1000 words. It didn’t take Wesley Tee long to get to the bottom of this, so he fired Mason – firing was always an activity he enjoyed – and, at a lesser salary, employed Boddy as the new editor.

But in 1939 came war, and the worlds of Brooklands, Donington, and wealthy young men enjoying themselves in motorcars came to an abrupt halt. Tee assumed it was the end of Motor Sport, too, but Boddy had other ideas. He persuaded the Old Man that he could keep it going in his spare time, even while he was doing wartime work at Farnborough, writing digests of aircraft manuals for service crew.

He got his friends and acquaintances in the car world to write reminiscences and chat pieces for nothing, and somehow during the long years of war, with no news to report and despite paper shortages, fuel rationing and myriad other difficulties, the magazine continued to appear, surviving on sales of 5000 copies a month.

While at Farnborough the Bod befriended a little bearded man who’d been posted there as an engineer. This was Jenks, and the two of them spent hours reliving their pre-war motor-racing memories, discovering in each a knowledge and love of detail that was to shape this magazine for the next half-century. When the war was over Jenks found he could race his 350cc Norton in European motorcycle races, using the meagre start money from one race to get him to the next. Soon the Norton expired, but top sidecar exponent Eric Oliver needed a new passenger. Jenks was fearless, and he was also very small. The minimum weight for the man in the chair was 60kg; in leathers, helmet and boots Jenks tipped the scales at 59.9kg, so with a couple of spanners in his pockets he was in. For 1949 the motorcycle world champions were Les Graham in the 500cc class, Freddie Frith in the 350cc class – and Oliver and Jenkinson in the sidecars.

Gordon Cruickshank scares himself in a gripless 1958 Corvette

A major plus for Jenks was that the European bike races often shared the same weekend and venue with the car Grands Prix, so he could ramble around the paddock to his heart’s content, and then report back to the Bod.

In October 1948 Britain’s first big post-war race, grandiosely titled the International Grand Prix, was run on a figure-of-eight course over the old runways and perimeter roads of a wartime airfield near the Northamptonshire village of Silverstone. The Old Man went up to see what the fuss was about, and took his 16-year-old son Michael, who still remembers the galvanising effect it had on him. “I’d seen this dull little magazine that my father printed, acres of grey type and virtually no photographs, and at Silverstone I couldn’t believe the colour and the drama: the red Maseratis, the green ERAs, the blue Lago-Talbots, the glamorous drivers in their linen helmets. I said to the Old Man, ‘This is marvellous. Why haven’t you got pictures of all this in your magazine?’ He took his camera from around his neck, gave it to me and said, ‘Here you are, boy, you’d better go and take some.’ So I did, standing totally unprotected on the edge of the track.

“The Bod wasn’t keen on pictures because it reduced the space for his words. And he would never allow any cuts to be made. If his copy didn’t fit, he would have it reset in smaller and smaller type as it went down the page, and if necessary there’d be a continuation onto another page – sometimes an earlier page in the magazine.” Motor Sport’s increasing band of faithful readers became used to these oddities, and treated them as the norm. “In fact the magazine wasn’t written for the readers. It was just a kind of private dialogue between the Bod and Jenks, and if the readers happened to enjoy it too, well, that was a plus.

“Jenks was permanently in Europe, going from race to race, and when I went out to do the photos I’d take some travellers’ cheques to keep him going, because there were strict currency regulations then. Jenks always had a healthy disrespect for any sort of authority. When the United States Grand Prix became a round of the World Championship in 1959 we needed visas to go to America. Jenks went to the embassy for his, and when he was asked, ‘Are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the Communist party?’ he replied, as a joke, ‘Only when we were on the winning side.’ The embassy chap folded up his paperwork and said, ‘I think you’d better have another think about that,’ and, to Jenks’ fury, his application was refused. So I had to write the race report as well as taking the pictures. In fact he always refused to go to a country he perceived as communist – so later on the Hungarian Grand Prix was always a no-no.

“During the 1950s the Bod was living in Hampshire, and he would come into the office for a few days towards the end of the month, when the magazine was going to press. At the start of the month he didn’t come in at all. And we wouldn’t see anything of Jenks from one month to the next. The Bod and Jenks were the only editorial staff members. There was an Irish lady called Molly Cronin who was The Old Man’s secretary, and somebody selling advertising. He didn’t have to work very hard, because as the magazine’s circulation went on rising, bookings came in through the window.”

But in those days journalists were expected to be kind about the products of advertisers, on the basis that it was the ads that, indirectly, paid their salaries. The Bod would have none of that, and his road tests always said precisely what he thought. When he lent his road-test Austin A90 Atlantic to Jenks, Jenks wrote a typically trenchant piece about what a dreadful car it was. Car manufacturers were used to universally flattering road tests in those days, with any criticism carefully concealed within a litany of compliments. So Austin’s publicity director, a man called Bishop, cancelled all Austin’s advertising – and the Bod gleefully told his readers all about the ‘Bishop Ban’.

Damien Smith retraces the Targa Florio in a Ferrari 458

Other aggrieved advertisers would complain to the Old Man, who relished a good fight and always supported what his writers had said. Mintex, the brake lining manufacturer, was a large client, and when its directors were upset by something the Bod had written their representative was sent to speak to Mr Tee.

The Old Man kept him waiting for an hour, and when he finally let him in he said, ‘I can’t quite understand why you’re here. I gather you represent a firm that makes peppermints’.”

In the early days Michael persuaded the Old Man that the cheapest way to get to overseas events was to charter a small aircraft, and sell off the spare seats. “I remember flying to Le Mans in an Airspeed Oxford, all fabric, with a panel in the roof where if you crash-landed you could punch a hole and climb out. We went through a violent storm and that panel blew off. We were sitting in the back with an umbrella up to keep the rain off while the Bod, unperturbed, typed his report with two fingers as always. Later on I learned to fly at a school at Elstree: they said they’d give me free lessons if I wrote it up in Motor Sport. We used to fly to lots of the Grands Prix, not without some dramas, and there were a few times when we were lucky to get back onto terra firma.”

As well as the writings of Boddy and Jenks, there was a third ingredient in each issue that made Motor Sport indispensable to the enthusiast: the small ads in the back, listing cars for sale. These were called classifieds, but in fact they were completely unclassified. The ads were simply run in the order in which they came in, making up a fascinating jumble of decrepit vintage machinery and battered old racing cars to plough through each month. Through the 1950s and the 1960s dealers with older, more oddball cars soon realised that Motor Sport had become the marketplace, and if they didn’t run ads there they wouldn’t get any punters. This growing profit line for the magazine wasn’t as a result of any commercial decision or marketing effort: it just happened. Most of today’s longer-established classic car dealers started out in business with an ad in Motor Sport, and most of them are still in our pages each month – although their asking prices have changed somewhat.

One of Mr Tee’s many foibles was that he didn’t allow any of his writers to use their full names, in case competitors approached them with more money to move to another magazine. Only initials were allowed, so the Bod was WB and Jenks was DSJ. In fact, they soon became so well known that everyone knew exactly who they were. The Bod, because he maintained that the Old Man paid him so little, would freelance for anybody and everybody, and Mr Tee turned a blind eye to this as long as it was not for a direct competitor. The by-line “By William Boddy” appeared in lots of unlikely places, including the soft-porn magazine Mayfair, in which eulogies about Alvises and Lagondas rubbed up against the gatefolds of naked ladies.

Jenks chatting with a young Striling Moss, who he would share the 1955 Mille Miglia winning drive with

GP archive

The Old Man was always adamant that only his own presses should print Motor Sport, even when that became commercially damaging. As Michael Tee points out, “His old letterpress machines were fine when the circulation was around the 50,000 mark, but by the end of the 1950s it was climbing steadily, and by the mid-60s it was more than 150,000. We could have saved a fortune by sub-contracting the print to a firm with more modern litho machines, and tightened up the schedules massively, but the Old Man wouldn’t have it.”

As British motor racing proliferated there was no way Motor Sport could cover it all, so in 1957 Mr Tee bought Motoring News. This was a curious, ailing monthly newspaper for economy-minded motorists filled with features like “Helpful Hints from AA Patrolman Pat,” but at one inventive stroke he relaunched it as a weekly covering the entire motor sporting scene, in which guise it survives to this day. In the gloomy rabbit-warren that was now called Teesdale Publishing it was joined by other titles, as Gordon Cruickshank remembers:

“Motorcycle Sport was run by Secret Cyril, who drifted in at noon and rarely spoke. War Monthly was about military history and edited by a married couple of hippy peaceniks. And there was Guns Review, which meant you might trip over an Uzi sub-machine gun being photographed in the studio. One morning the place was full of police because an escaped prisoner had broken in and stolen that month’s featured guns.”

Michael Tee also developed the growing archive of his own and others’ photographs into a picture library called LAT, which generated extra profits by providing other publications and advertising agencies with a fine resource of motor racing shots. But he eventually grew tired of the endless arguments with his father and left to set up a motor sports promotion company, which became very successful. In 1972 Clive Richardson joined with the double role of assistant editor of Motor Sport and performance editor of Motoring News. “The pressure on me was pretty great, because as far as Motor Sport was concerned I was having to put the magazine together myself. The Bod had already moved to Wales by then and sent his copy in by post. He would only come in once a month for the editorial meeting, with a list of complaints. Jenks complained, too. His copy often arrived late, and was usually over-written. Sometimes whole sections had to be cut from the issue after it had been planned so that the Old Man’s machines could cope. But as far as the Bod and Jenks were concerned, it was always my fault. I’ve lovingly kept this letter Jenks wrote to me:

“‘Dear Clive, I am very pissed off with you for leaving out my From the Archives piece. It makes me look a twit to people whom I told it would be in the January issue. I have written to Mr Tee to lodge a formal protest. I am very tired by your continual whingeing about being unable to get things in the space. Before you appeared on the scene the Bod always seemed to manage. I am writing this moan to you as I could not stand listening to your feeble and half-arsed explanations. Take it as read that I am very pissed off with you, and that is all there is to it. Cheers, Jenks.” Of course, when I next saw Jenks he was fine. Once he’d vented his spleen he was all right.

Printer-turned-publisher Wesley J Tee saved the magazine in the 1930s and remained involved until his death in 1996

Motorsport Images

“Molly Cronin, who’d joined back in the 1930s, was still there when I arrived, but she’d begun to deteriorate. I’d draft out letters of reply to people who’d sent in photographs or comments, and the Bod, when he was in, would also write a few for her to type. When she stopped coming in I opened the drawers of her desk, and they were full of years of unsent and unanswered letters. In the bottom drawer were several empty gin bottles.

“I got several good job offers, tried to leave, and each time the Old Man persuaded me to stay. In among all that he sacked me as well, I’ve forgotten why, but he reappointed me the next day. I stayed because I loved it, but after 10 years I’d had enough.”

Gordon Cruickshank came down from Scotland to apply for a job on Motoring News as a rally reporter. “I went all the way to London, only to be told the job was filled. When I got home there was a phone call saying they might be able to talk about another job, and I went back down again. Mr Tee didn’t discuss anything with me: he just said, ‘You’ll be starting on Monday, boy, at this salary.’ I found myself Assistant Editor of Motor Sport, running the whole magazine on my own.

“The Old Man called everybody Boy – even the Bod when he was in his 70s – because he couldn’t remember anyone’s name. In the monthly meetings, in a stuffy dungeon at the back, he relied on where you were sitting to identify you. So if you sat in the ad manager’s usual place he’d ask you for the advertising figures. It was easier to invent something than to argue. Sometimes he would nod off, and we would talk on quietly until he rejoined us.

“His meanness was legendary. Letters had to be sent second class unless vitally urgent. You weren’t allowed to make telephone calls out of London in the morning, only in the afternoon because the rate was a bit cheaper then. Kath Roberts, who had replaced Molly as the Old Man’s secretary, checked everybody’s expenses, and she knew to the nearest mile how far it was to Oulton Park or Castle Combe. You always had to share hotel rooms, and you’d only be allowed a few quid for that. Michael will tell you that even in the 1950s, finding a hotel room in Monaco for £5 a night was a problem.

“Of course salaries were ludicrously low. My first December I was astonished to discover in my pay packet a surprise £70 Christmas bonus. Then in January my pay chit said ‘minus £70 Xmas advance.’ But company cars were generous – Golf GTis, Lotus Cortinas, TVRs – because the Old Man realised that it was cheaper to give a staff member a nice car than to pay them more money.

“Planning the issues while dealing with The Bod and Jenks wasn’t easy. I’d say to Jenks, ‘How many pages do you want for the Dutch Grand Prix?’ He’d say, ‘If it’s interesting, I’ll do eight pages. If not, I’ll do half a page.’”

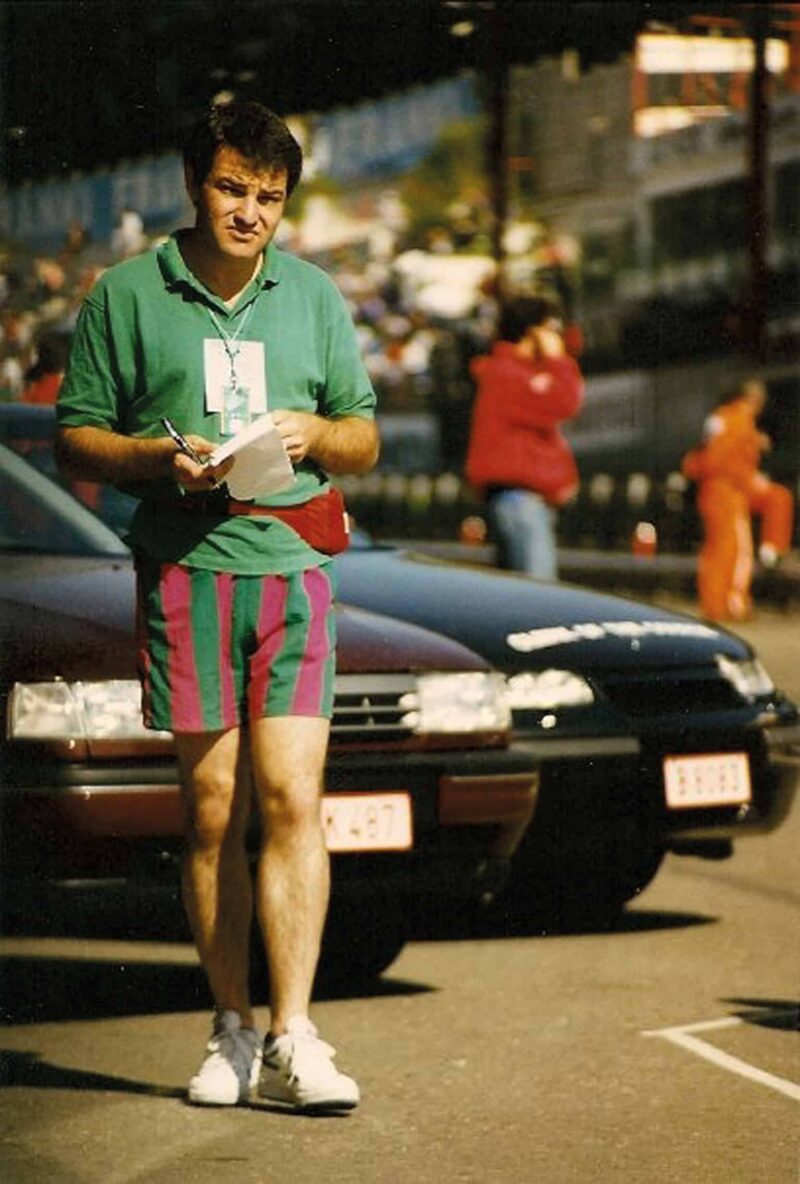

Simon Arron displays traditional green Motor Sport stripes at Spa in the 1980s

In 1989 Gordon went to Germany to cover a new-car launch. He was a passenger in a Mercedes being driven by another journalist when the car crashed and turned over. The driver was unhurt, but Gordon’s neck was broken. His convalescence took more than a year, and he had to come to terms with the fact that he was now paralysed from the chest down, and would never walk again. He taught himself to use a keyboard with his thumbs, and it is an immense tribute to his courage and his stoicism that he has continued to be a first-rate journalist and feature writer. He is now deputy editor, and in his spare time enjoys driving his restored Jaguar 3.4 Mk2, which he has had fitted with hand controls. His time on Motor Sport now totals 32 years.

Into the 1990s, although the actual work of editing the magazine continued to be done by somebody else, Bill Boddy was still called The Editor. The circulation had been falling steadily for more than 10 years, and was now below 40,000 copies a month. At this point Simon Arron entered the picture. “I came onto Motoring News straight from university, but after six years I left to join another title. But I stayed friendly with the MN gang, and on Tuesday evenings they used to have a light-hearted game of five-a-side football, and I’d go over to join in. When I walked in one Tuesday in 1991, I was told the Old Man wanted to see me. As I stood there in my football strip he showed me a letter from a reader complaining that the magazine’s content no longer reflected its title, with too much vintage stuff and not enough about contemporary racing and F1. ‘I’d like you to come back and address this,’ he said. When I asked what my title would be, he said, ‘You’ll be editor.’ The only drawback, of course, was that he didn’t tell Bill Boddy.

“After I’d been there a couple of days the Bod came on the phone from Wales and said, ‘I want this and this to go in the next issue.’ I said, ‘Well, what I’ve got planned is…’ ‘What do you mean, what you’ve got planned? Aren’t you the new copy boy?’ So I went to see the Old Man, and told him I’d just had Mr Boddy on the phone. He smiled mischievously, and said, ‘What was that like, boy?’ It all calmed down in the end, the Bod went on doing what he’d always done, I got the magazine out, and the Bod was called Founding Editor after that.”

Bill Boddy continued to write for Motor Sport, in the same tone of voice and still concentrating on the subjects that interested him most, from vintage cyclecars to Brooklands, right up until he died, aged 98, in 2011. By then his work had been in these pages for over 80 years, thought to be a world record for continuous contribution to any one periodical. To the end his knowledge and his recall continued to be prodigious. The Vintage Sports Car Club, formed in 1934 largely at his suggestion, called him the single most important figure in the old car movement.

Never one to offer praise where none was due, WB evaluates a Humber Super Sniper estate

Motorsport Images

Jenks, of course, gathered greater fame when he reprised his fearless passenger role with Eric Oliver by going with Stirling Moss in the victorious Mercedes 300SLR on the 1955 Mille Miglia. Much later I got to know him well because I was a sort of associate member of the exclusive group – consisting primarily of Jenks, Nigel Roebuck and Alan Henry – that gathered in the press rooms of Grands Prix around the world to gossip, chortle and complain. Jenks liked the fact that I was BBC Radio’s F1 commentator, because he regarded the BBC as a Good Thing. He didn’t have a TV in his tumbledown cottage in Hampshire: indeed, he didn’t have mains electricity. When power was required he would start up the Fiat Topolino engine bolted to the floor in the front passage which drove a generator that lit six-volt bulbs hanging from wires draped at Jenks-height from the floor. But he did have a battery radio, and if he didn’t go to a Grand Prix, or if he wanted to keep up with progress from the Le Mans 24 Hours race, he would switch me on.

But in time, as Simon Arron found, Jenks became dismayed by what he saw as the galloping commercialism taking over Formula 1. “He would only ever go to the races that interested him, and the Motoring News F1 reporter – first Alan Henry, then David Tremayne – would be required to fill in for the ones he missed. The readers still loved him, of course, and I did all I could to keep him on side, but his interest was dwindling. I remember saying to him. ‘Write about whatever you want, the world is your canvas. For example, nobody knows much about Castellotti, but you do.’ He replied, ‘I’m not interested in Castellotti.’ In the end he had some sort of bust-up with the Old Man, and started freelancing for Autosport and other magazines. He never formally left Motor Sport: he just kind of disappeared.”

Wesley Tee continued to run the business in his usual autocratic way, but things were no longer going well. By 1996 more and more magazines had entered the market to compete with Motor Sport, many with more pages, glossier layout, and a broader appeal to a younger generation. By 1996 the circulation, which had been falling steadily from its 1967 peak of 163,000, was less than 27,000 copies a month. In August of that year Wesley Tee died, after 60 years at the helm. One major magazine publisher which had been trying to buy Teesdale for many years hovered, ready for the kill, and its managing director even turned up at the Old Man’s funeral. But the Tee family decided that a better purchaser would be Haymarket Magazines, which took over Motor Sport, Motoring News and the LAT photographic business at the end of 1996.

Smith is in his second stint as editor, while Cruickshank has been a staffer for 32 years and counting

Haymarket’s publishers added more pages, more colour and more good writing, and the circulation began to climb again. Andrew Frankel and then Paul Fearnley took over the editor’s chair. Meanwhile Motoring News became Motorsport News, and LAT was greatly expanded to include the archives of the other Haymarket motoring and motor-racing titles. Then in 2004, in an effort to get more visibility on the bookstalls and in a marketing decision that in hindsight was ludicrously wrong, Motor Sport was relaunched with a new design that ditched the much-loved green cover for red. Many indignant readers thought it had always been green, although in fact the magazine was already 28 years old when the green cover, with its curious vertical white lines, was introduced in 1952. But the change sent the wrong signals to many loyal and long-standing readers.

The following year Damien Smith took over as editor for nine months before being promoted into another job within Haymarket, and it fell to him to defend Motor Sport against its anti-red critics. “In fact Haymarket deserves credit for breathing new life into the magazine, because it was at a very low ebb when they took it over. Because they had other titles dealing with modern racing they decided to move it much more into the areas of history and historic racing. Of course that red cover, which came in before my editorship, was quite wrong. It only lasted for 20 issues – out of 1067 so far! – and it was nearly 10 years ago. But we still get beaten up about it.”

By June 2006 Motor Sport was green again and, after Haymarket had granted a licence to another publisher for a period, the title was purchased outright by business entrepreneur and long-time Motor Sport reader Edward Atkin. He had a perfectionist vision of how, with proper investment and direction, this magazine could expand its quality coverage of the entire motor sporting scene, historic and contemporary, while maintaining the highest standards of stimulating writing and superb photography. Under his ownership it has developed into what you now hold in your hands.

Of course it is now a very different magazine from what it was 90, or even 20, years ago. Yet, in a remarkable way, it still follows the same precepts, the same principles, that it has always done. And in the place of the Bod, Jenks and the Old Man it still has three crucial players who may not think of themselves as eccentrics, but are nevertheless unshakeably true to their own beliefs.

Damien Smith, who returned as editor in 2008, could hardly be more different from Bill Boddy, and is certainly more aware of his editor’s role in giving the readership the stimulus and creative variety it has a right to expect. Yet, just like the Bod, he is determined to produce a magazine that will always maintain high editorial standards and remain true to its principles. In Nigel Roebuck Motor Sport has the nearest thing to a modern-day Jenks, a writer who is able to bring an unrivalled historical perspective to modern-day motor racing, and enjoys great respect because of that, not only from his readers but also from people inside motor racing. And Edward Atkin won’t thank me for comparing him to Wesley Tee, yet like the Old Man Edward is an uncompromising individual who will not be diverted from how he has always believed his businesses should be run. Motor Sport survived because Wesley Tee ensured that it did. Motor Sport now thrives because Edward Atkin ensures that it does.

I’ll let Damien Smith have the last word. “One thing I have to mention is the camaraderie in the office. We’re not just a magazine now, of course: we have a busy website and tablet editions which have expanded our reach enormously. And the editorial team has grown a fair bit, too: as well as me and Nigel and Gordon and Simon, we have F1 guru Mark Hughes, online editor Ed Foster and art editor Damon Cogman, who has to make the magazine look appetising and readable. And we’re proud of our great roster of regular contributors too – including you and your Lunches! Binding us all together is the weight of 90 years of history, and the responsibility to keep Motor Sport what it has always been: genuinely, unyieldingly for the serious enthusiast.”

In 10 years Motor Sport will celebrate its centenary. Motor racing, having changed beyond all recognition, will inevitably change a whole lot more in the next decade. So, no doubt, will the business of publishing monthly magazines. But after Motor Sport’s roller-coaster ride since 1924, I’m sure it’ll still be here for you. The spirit of the Bod, Jenks and the Old Man will live on.