Lunch with... Peter Warr

The former Lotus team boss remembers the early days with Chapman, his struggles with Senna, and a certain ‘uncouth Brummie’…

James Mitchell

At its zenith, Lotus was Formula 1’s most consistently successful team, winning 71 World Championship races in 19 seasons. Ferrari’s tally for that same period was 44. Any list of the all-time greatest F1 cars must include at least four Lotuses: the monocoque 25, the DFV-pioneering 49, the wedge-shaped 72 and the ground-effects 79. Those types alone won 52 Grands Prix.

For 25 of its 37 seasons in F1, Team Lotus was powered by the restless genius of Colin Chapman. And for most of them Peter Warr was there: as Chapman’s right-hand man until the Lotus founder’s sudden death in 1982, and then as team boss for seven more years. During his career Warr worked with an extraordinary roster of drivers, including 11 current or future World Champions, and was on the pitwall for well over 300 F1 races. Few can match his knowledge of F1 through the 1970s and ’80s, not only from the Lotus perspective but also as long-time keeper of the minutes in FOCA meetings. And no-one knew Colin Chapman better, or worked with him more closely.

Peter and his wife Yvonne live in south-western France now, in a charmingly eaved and turreted house on a wooded hill. All around, vineyards fill the view. We take lunch in the Hostellerie de Plaisance in St-Emilion, and Peter orders local foie gras and scallops. As we’re in the heart of the Bordeaux region the wine list is terrifying – the 1950 Petrus is £3400 a bottle – but Peter tactfully opts for a humbler 2003 Chateau Tour de Pas, costing a hundredth of that.

“There was always a complete lunacy about working for Colin. He believed there was no reason on God’s earth why an idea he’d just had couldn’t be on the cars for the coming weekend. But his leadership, his ability to motivate, was such that people would start to believe it could be done, and they would perform way, way beyond their self-believed capabilities. If he said, ‘Right, lads, today we’re all going to jump off this cliff,’ they’d do it. He’d jump first, and they’d all follow him.

“You cannot believe the hours people worked in the early days. Bob Dance [the legendary Lotus F1 mechanic] reckoned he was doing 73 hours a week on a regular basis – but on a Grand Prix weekend he’d clock up those 73 hours from Thursday to Sunday. Everybody was scared stiff they’d make a mistake and get on the wrong side of Colin – his temper was fairly violent, and he had a very short fuse. He’d come round and say to someone on the shop floor, ‘You’re meant to be the welder. I could weld that, so why the hell can’t you do it right?’ He could perform pretty much any task in the factory, and everybody knew it. If you survived working for him long enough to learn to understand him, you realised what an incredible mind the man had.

“He’d go into the drawing office and look over the draughtsman’s shoulder and say, ‘No, no, no, that’s not what I want at all,’ and he’d grab his pencil and sketch on the side of the drawing to show him. And if the draughtsman didn’t produce exactly that, Colin would go on at him until he did. If someone else had an idea he’d listen, and sometimes it would suddenly become his idea. But more often he’d look at it from a completely different angle and he’d say, ‘Why don’t we take it a step further, why don’t we do this?’ And you’d think, ‘Bloody hell, he’s done it again’.

“He didn’t actually invent very much. Aerodynamics had existed before the Lotus Mk 8. Monocoques had been made before the war. Ground effect wasn’t totally new. His genius was to be able to take an idea, refine it, adapt it, think it through from a different direction, and say, ‘I can use this in a racing car application.’ Then he’d engineer it so it worked how he wanted it to work.

“His temper rarely lasted for more than a few minutes. And he could be incredibly generous. His most annoying characteristic was he was almost always right. You’d think, ‘He’s really gone off his rocker this time, I’m going to have it out with him’, and nine times out of 10 the bugger would turn out to be right. But when he did get it wrong he made some big ones.”

In 1958 the 20-year-old Peter Warr made a pilgrimage to North London to take a look at the little Lotus factory behind Stan Chapman’s pub, the Railway Hotel in Hornsey. “We lived near Brands Hatch and I loved the small sports car races, the bob-tail Coopers fighting it out with the Lotuses: the Mk 8, the first aerodynamic one, then the Mk 9 and the Eleven. When I got to Hornsey I was told, ‘You can look around, but don’t get in anyone’s way.’ Then someone said, ‘Don’t just stand there, give us a hand.’ Next day I was on the payroll, a gofer at £9 12s a week.

“The F1 car that year was the 16, the mini-Vanwall. I remember Mike Costin giving the chassis a shakedown around Hornsey, roaring through the busy streets in a bodyless racing car. By the time the police arrived the car was back in the shop, up on trestles, wheels off. Fortunately none of the coppers thought to put a hand on the engine to see if it was warm.

“Lotus’ business was selling racing cars to the public. The Lotus 7 hit a more affordable road/race market, and then Colin decided he wanted a sexy GT, and that was the Elite. We were split up into Lotus Cars, which was the Elite; Lotus Components, which built the customer race cars; and Team Lotus, which was the works racing operation. I ended up running Lotus Components. I’d demonstrate cars to customers by giving them a 120mph blast around the North Circular. It was a big responsibility, because the profits from Lotus Components were holding up the rest of the company. The first rear-engined Lotus, the 18, was all-conquering in Formula Junior, and we couldn’t make them fast enough. We built 125 in 1960 alone.”

In 1959 Lotus was bursting out of its premises in Hornsey and Edmonton, and moved to slightly more spacious premises in Cheshunt. “I bought the Climax-engined Lotus 7 demonstrator for £750 and raced it for two seasons. Did 30,000 road miles in it, too. Then I did Formula Junior with an 18 and then a 20, towing to continental races on Friday night straight from work. I also took a 23 sports-racer to the first Japanese Grand Prix at Mount Fuji, and I won it.

“Components did a lot of the work for Team: it was all one family. Jim Clark, out of the cockpit, was just an ordinary guy, a bit timid really in the early days. He’d stick his head apologetically round the door to ask the girl who ran the petty cash if he could borrow a fiver, and write out an IOU. But, like all the great drivers I worked with, he was incredibly competitive. Colin and Hazel had a party at their house, and somebody found a pogo stick belonging to one of the kids. So there was a £5 bet: who could get up to the first floor without touching the wall. Hazel’s wall lights got broken, there was a fair amount of debris, and no-one could do it. Suddenly Jimmy was going boing, boing, boing up to the landing. Effortless. Later on he changed a bit. He’d been living in Paris, seen more of the world, and maybe felt Colin had taken advantage of him.

By the end he was prepared to stand up to him over money and things like that.

“Alan Stacey was very fast. He’d lost part of his right leg in a motorcycle accident and couldn’t heel-and-toe on downchanges, so we rigged up a twist-grip hand throttle on the gearlever. He didn’t deserve to have his life taken like that, hit in the face by a bird at Spa. His car plunged over a drop and caught fire, but he can’t have known anything about it because the bird, which smashed his visor, must at least have knocked him out.

“In 1966 Lotus moved from Cheshunt to Norfolk. I helped plan the new factory at Hethel, but after several trips up there I decided I didn’t want to make the move. Also I suppose I’d made myself pretty indispensable at Lotus Components, so the one job I really wanted, to run Team Lotus, I wasn’t going to get. So I left. I started a slot car racing business, but it wasn’t a successful venture. Then Andrew Ferguson, the Team Lotus team manager, told me he’d had enough, so I rang Colin. I started at Hethel in October 1969, the day after Graham Hill smashed his legs at Watkins Glen.

“Maurice Phillippe was in the throes of designing the Lotus 72, working in secret in a separate flat behind Colin’s office. Team Lotus consisted of 45 people then, and it wasn’t just F1. We were doing the Tasman Series, Indianapolis, Formula 3, and GT racing with the 47s. The total personnel at a Grand Prix was nine: two drivers, two mechanics on each car and one on the spare, me and Colin. There were the non-championship F1 races too, which Colin usually didn’t come to, plus all the testing. Looking back, it seems staggering what we got done, but it was fun. In F1 these days I don’t think they do fun.”

Jochen Rindt was coming to the end of his first season with Team Lotus, and it hadn’t been a smooth ride. “Things between Jochen and Colin were always difficult. Some of it came out of Jochen’s close relationship with Bernie Ecclestone, who managed him. Bernie had lost Stuart Lewis-Evans because of a mechanical failure [his Vanwall’s engine seized at Casablanca in 1958, and he crashed fatally] and he wasn’t keen on Jochen coming to Lotus because of its reputation for fragility. If I had seven days with you I could go some way to persuading you that by 1970 it was an undeserved reputation, but the reputation was there. With the reliability problems in 1969 Jochen had got crosser and tetchier, which didn’t sit too well with Colin. After his easy relationship with Jimmy, he wasn’t used to having an argumentative driver with forthright views.

“However, Jochen was hugely excited by the 72, and 1970 was a new start. But from its first race in Spain we found having anti-dive in the front suspension and anti-squat in the rear just didn’t work. All it did was jack up the inside of the car and make it impossible to handle. After Spain Jochen refused to drive it, and raced the 49. We got stuck into an enormous programme of modifications – during which Jochen won Monaco in the 49 – and the revised car was all done for Zandvoort. Jochen pissed it, took pole and pretty much led all the way. Piers Courage was killed that day, which was dreadful, but we finally had a world-beater. Jochen won four on the trot, and made his famous remark: ‘This car is so good a monkey could win races in it.’

“Jochen was incredible behind the wheel of a car, but he did reveal the odd frailty as a racing driver. He wasn’t too keen on testing; basically he just wanted to turn up and drive. And there was that thing of being sick in the car. He’s the only driver I knew who did that, apart from James Hunt. With James it was nerves, but with Jochen it was motion sickness.

“In Austria, his home Grand Prix, the engine blew, and John Miles drove the other 72 slowly back to the pits after an inboard front brake shaft broke. I think it was a one-off manufacturing fault, but it was a failure which was to come back and haunt us. When we got to Monza three weeks later the 72 wasn’t that quick in a straight line, mainly because it had such wonderful downforce. Jochen said he wanted the rear wing taken off. It had never run in that configuration, and Colin was against it, but Jochen insisted he wanted the wing off and a 204mph top gear, for ultimate straightline speed. But he didn’t adjust the brake balance, and without the downforce of the rear wing it would have had too much braking on the rear. Firestone had a hard rear tyre for the left side and a softer one for the right, because Monza is mainly right-hand corners:

the harder tyre took longer to come in. If you add all those things together you’ve got the ingredients for an accident.

“Jochen went out to qualify on the Saturday morning, and I think quite simply when he got to the Parabolica, with too much braking on the rear and the left rear tyre not fully warmed up, he hit the brakes and the car started to fish-tail. It went one way, he caught it, it went the other way, and barrelled into the Armco. The nose went under the Armco and the car swapped ends, and went along it backwards. That tore the front pedal box off, which dragged him down the cockpit because he wasn’t wearing his crotch straps – he never liked them – and the lap belts broke his neck. I am convinced that the front brake shaft was broken by the impact with the barrier, and did not break before the accident and cause it. We went on to use the same shafts on the 72 for six seasons.

“Jochen must have been dead within seconds of the impact, but they went through the performance of getting him out of the car, taking him to the medical centre, putting him in the ambulance, and then saying he died on the way to hospital. This was because of the stupidity of Italian law: if there’s a fatality they have to have an inquest on the spot, and it would have cancelled the race. It was the same with Ayrton Senna at Imola: they said he died in the helicopter. Colin knew about the Italian legal system because he’d had the thing with Jimmy and von Trips at Monza in 1961, so he needed to leave quickly. I took him and Nina straight to the private aircraft terminal at Linate and went back to sort out what was left. I had to get a lawyer, I had to identify him, I had to deal with the undertakers, and I bought a scarf from somewhere to cover up his neck.”

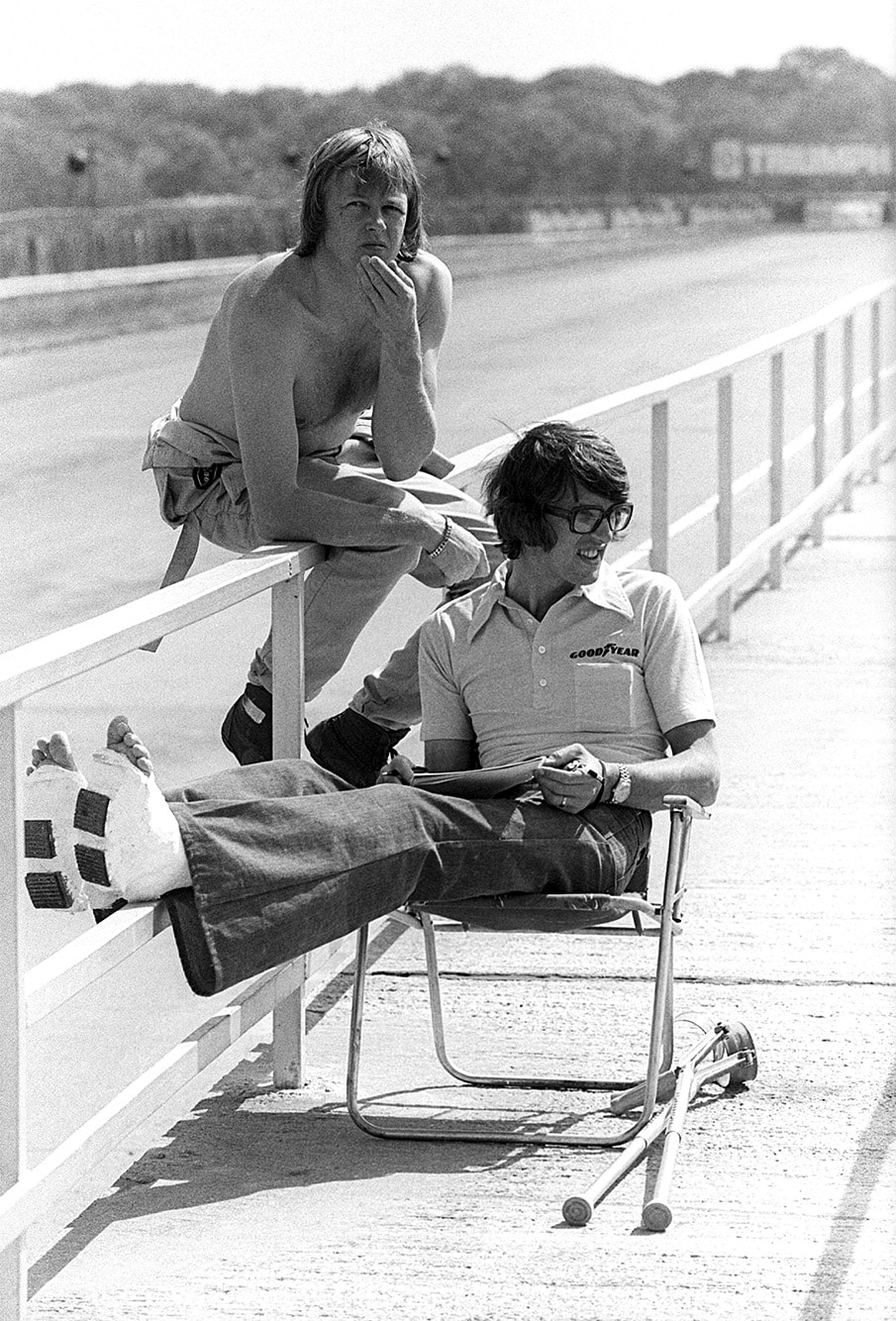

Warr, with feet in plaster after a road accident, sits with Peterson

Sutton

It was a crushing blow for Team Lotus, and yet the next race they went to, Watkins Glen, Emerson Fittipaldi won. “Well, Emerson didn’t so much win as Rodriguez stopped [for fuel with eight laps to go]. But racing is littered with things like that. An event like Jochen’s death makes you get your head down, not talk to anybody, shut out the rest of the world. You just want to get on with your job. Jochen’s car, 72/2, was impounded in Italy. Emerson had destroyed his brand new car, 72/5, in his Monza crash on Friday – that was driver error – and we had to make an entire new car for him very quickly. No-one who wasn’t in F1 in those days can really grasp how hard you worked, and how desperately last-minute everything always was.

“Emerson was bloody good. In 1971 he was still learning his craft as team leader, and his English wasn’t so hot. In testing he’d come in and say, ‘Check the chuckers overs’. It was some time before we twigged that chuckers overs was his way of saying shock absorbers. Then we had a breakthrough with the 72. The front leg of the rear wishbone was attached to the bellhousing and the rear leg was attached to the gearbox, and when they got hot they expanded at different rates and the wishbone was bending. We changed to double link rear suspension and it transformed the car. For 1972 we were JPS, smart new livery, and Firestone were making us special tyres, because the 72 had radical weight distribution, heavily biased to the rear. Emerson delivered that year: the youngest World Champion at 25.

“He didn’t get much help from Dave Walker, which was a disappointment because he’d done a brilliant job in F3. He was fit and aggressive, but he lacked throttle control. In F3 the throttle was like an on-off switch, but DFVs were still quite peaky in those days, and he never got to grips with that. Of course, he could have won the Dutch GP in ’71. He was in the 56B turbine: 22nd on the grid, pissing with rain, he had four-wheel-drive and Firestone wets, and with 75 gallons on board the car was so heavy you couldn’t possibly spin it. I said to him on the grid, ‘Take it easy for the first 20 laps, let the race come to you.’ But he went mad, passed 12 cars in the first five laps, and then went straight on at Tarzan and filled the engine with sand. Silly idiot.

“For 1973 we felt it was time to have two top drivers. I had infinite admiration for Ronnie Peterson, so he joined us alongside Emerson. Colin engineered Emerson’s car, I ran Ronnie’s. Of all the drivers I worked with I got on with Ronnie best, as a friend. It was obvious to me he was the fastest thing out there, by a long way. He wasn’t perfect, because if there was a problem with the car he’d just drive around it. We were testing at Ricard, and Ronnie came in and said, ‘It’s understeering like shit.’ We took the tyre temperatures, and the rears were way hotter than the fronts, which meant it was oversteering, but Ronnie wouldn’t have it. So I went out to Signes – the 170mph right at the end of the long straight – and watched him. Huge opposite lock slide, smoke streaming from the rear tyres. Back at the pits I said, ‘Ronnie, what you’ve got there is called oversteer.’ ‘No’, he said, ‘the car’s understeering so badly I have to throw it sideways to get through Signes without lifting.’ It was one occasion when he gave us the right information: the car was telling us something else, because as usual he was driving around the problem. The only way he could drive a car, testing, practice, race, any time, was flat out. Nearly every other driver I’ve worked with would back off a little from the absolute limit in testing, but not Ronnie. He was priceless.

“Emerson didn’t take Ronnie’s arrival very well. What really got him going was he’d set his car up very carefully and precisely, and Ronnie would be off on a different tangent altogether. Just before the end of practice Ronnie would say, ‘I don’t know what’s going on here, what settings has Emerson got?’ And we’d put Emerson’s settings on his car and he’d go out and put it on pole.

“After Maurice Phillippe left, Ralph Bellamy designed the Lotus 76. It was meant to be a lighter 72, keeping the good bits and leaving out the bad bits. But it was a disaster; it was actually heavier. We experimented with an electric clutch, operated by a button on the gearlever, and there were twin brake pedals so the driver could brake with his left foot. Ronnie wasn’t getting on with it very well, so we fitted the same set-up to his Elite road car so he could practice.”

By the start of the 1976 season, with the complex fully adjustable Type 77, Team Lotus fortunes were at a low ebb. An unhappy Peterson left after the first round in Argentina, at Kyalami there were problems with the rear suspension coming apart, and at Long Beach Gunnar Nilsson crashed, again with a rear suspension problem. “Colin had a huge row with me about that. It was clearly a design fault, and I said to him, ‘No, Colin, you’re not going to pin that on me.’ Colin realised he’d gone too far, and when he’d calmed down he gave me a new briefcase with a letter of apology inside.”

The 77 improved during the season, helped by the arrival of Mario Andretti. “He was a superstar, extremely intelligent. We paid him a retainer and so much per championship point. First time that had been done in F1, I think. But I was still subject to what we called DFV syndrome (when it wins it’s a Ford victory, when it loses it’s a Cosworth failure). If we did well it was Chapman’s win, if we didn’t it was Warr’s fault. So when Walter Wolf told me about his new team with Jody [Scheckter] and Harvey [Postlethwaite], and asked me to come on board, I said yes. I wanted to see whether I could do things on my own, away from the umbrella of Colin. Before Monza I told Colin I was leaving. Bless him, he said, ‘We won’t say you’re leaving. We’ll consider it a leave of absence.’ He could’ve been shitty about it, but he was fantastic, and we remained friends. That was the bloke.”

Peter was away from Lotus for four seasons. The Wolf team made history by winning its first Grand Prix, but by 1979 Walter was gone and Wolf merged with Fittipaldi. “Walter wasn’t the easiest man, brash and loud and in your face, but he came into F1, did as much as he wanted to do, paid all his bills, and left. He didn’t disappear into the night owing anybody anything, as others have done. But the Fittipaldi period was difficult. From Wolf, with adequate funding, Castrol sponsorship, good deals with Goodyear and Cosworth, you go to Fittipaldi where you have to pay for everything, even your tyres. Wilson Fittipaldi was a good level-headed businessman, but the money was coming from Brazil, where there was rampant inflation and sponsors who didn’t understand that promises had to be met. Wilson kept everything going, but at one stage Emerson had to use his own money to keep the team afloat.

“Ronnie’s accident happened at Monza in 1978, while I was at Wolf. James Hunt was still driving for McLaren, but he’d already signed for Wolf for 1979. He got out of his car when the pile-up happened to try to help Ronnie. During the long delay before the restart he sat in the Wolf motorhome and pleaded with me to let him out of his contract. James was a brave, straight-up sort of guy, but he was always too intelligent, and after what’d happened to Ronnie he’d had enough. He wanted out. I just said it wasn’t the right time to make a decision like that. Ronnie was badly injured, but we didn’t know he was going to die. Later on we met and James decided to go ahead for 1979, but I remember thinking at the time the stuffing had gone out of him, and we weren’t going to get our money’s worth.

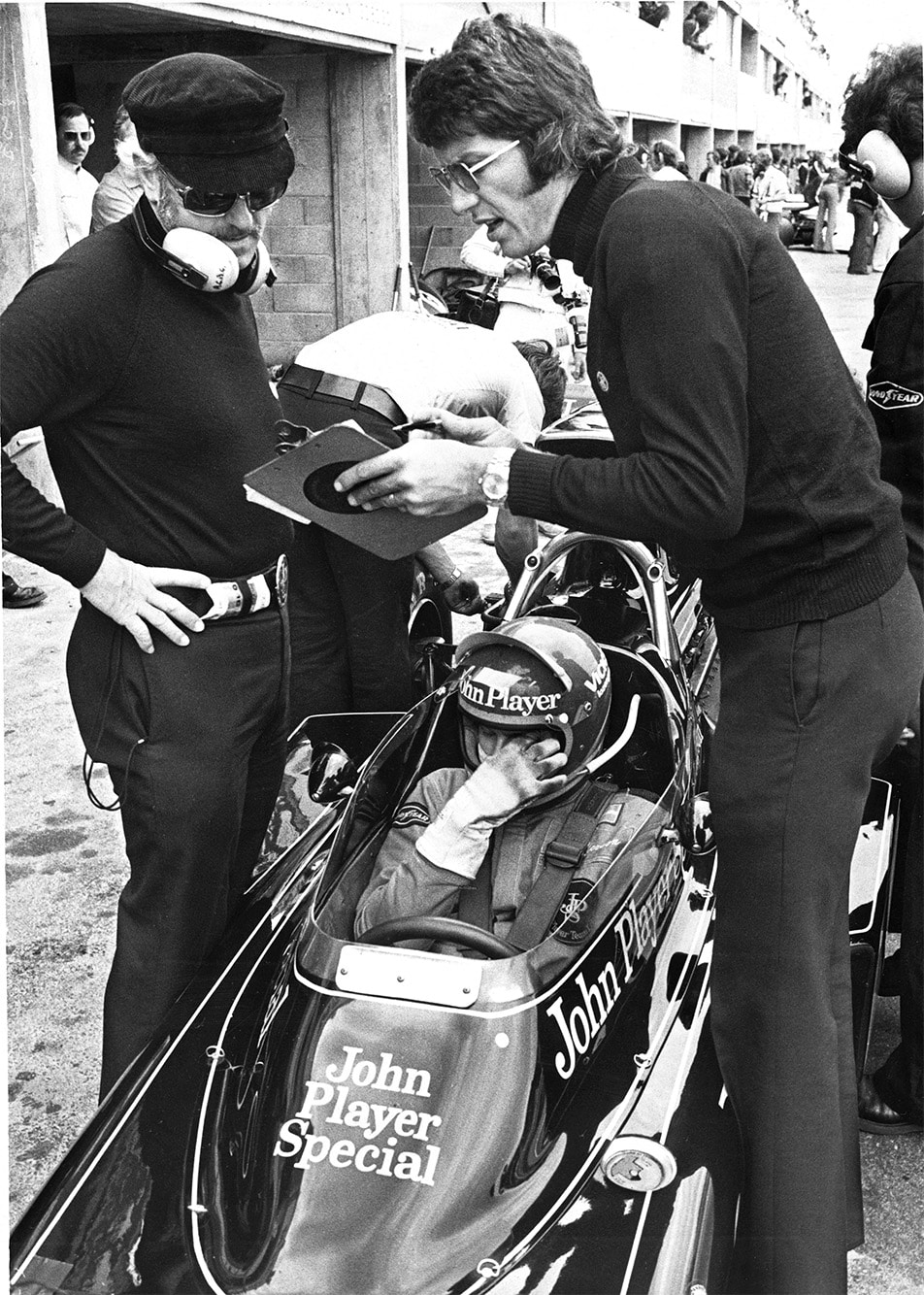

Chapman and Warr confer, while Peterson waits. Ronnie won seven GPS in the 72

Motorsport Images

“Later, one of the mechanics told me James said to him: ‘I’ve discovered that if I nudge the car up against the barrier and give it a squirt of throttle in second gear, it breaks a driveshaft.’ At Monaco, four laps into the race, he stopped up the hill by Rosie’s bar, with a broken driveshaft. Then he told us he was retiring. So I flew to America, where Keke Rosberg was doing Can-Am for Paul Newman, and got Newman to agree to release him.

“While I was away from Lotus, Colin’s thing with the DeLorean project was going on. I’m pleased I missed that, because if I’d been there who knows what Colin might have asked me to do… Then he called and said, ‘Do you fancy coming back?’ My leave of absence was over.

“I found Colin had changed while I’d been away. John DeLorean and [Essex sponsor] David Thieme introduced him to the high life, staying in the Hotel de Paris, the black and gold helicopter to ferry him from airport to circuit, the black and gold Lotus to get him from helipad to paddock. Instead of being in the garages until 11pm trying to work out solutions to problems and writing job lists, 15 minutes after practice he was gone, back to the five-star hotel.”

Then, one night in December 1982, Colin Chapman died of a heart attack. At 54, the axis of Lotus was gone. “It was the most dreadful shock. The aftermath of his death was very difficult. Because of unpaid sums in tax, the Inland Revenue froze his estate, which meant we were completely hamstrung as a company.” But, with Warr at the helm, Team Lotus carried on.

“When I returned to Lotus, Elio de Angelis and Nigel Mansell were the drivers. Elio was a lovely guy, smoked, drank whisky, played classical piano, beautiful girlfriend, loved driving racing cars. Maybe he wasn’t hungry enough – he was from a very wealthy, patrician Roman family – but he did it all with style. In the next pit was an uncouth Brummie who didn’t know how to handle himself. Mansell’s difficulty was he had this terrible chip on his shoulder, thought the whole world was against him. So he just whinged. He wasn’t honest with himself: he believed he was a superstar before he was.

“Mind you, he was incredibly brave on high-speed circuits. I’ve never seen anyone like him in quick corners. No-one ever doubted his bravery. That’s why he went so well on the American ovals. But he wasn’t clever. When he hit Giacomelli at Montréal in 1982 he twisted his wrist. He missed Zandvoort but wanted to do Brands Hatch. We had Geoff Lees standing by, but he said no, he had to do the race ‘for his public’. Then he came in and retired a perfectly good car, saying he was in pain.

“Don’t even talk to me about Monaco ’84. We had the right tyres for the conditions, the right engine programme, everything was perfect – as he demonstrated. But instead of leaving Prost at half a second a lap, which would’ve won him the race, he left him at two seconds a lap. Then he hit the Armco. He blamed it on the white line. We all know white lines are slippery when they’re wet, and every other driver had to deal with them. By not using his head he threw away a win which would have done him, and the team, a lot of good. Then, with the suspension bent and the rear wing hanging off, he drove it down the hill to Mirabeau, and hit the Armco again. It just highlighted the fact that he wasn’t that good.

“I’d been keeping my eye on this young Brazilian Ayrton Senna da Silva in F3, and in September 1983 I invited him up to Lotus. I showed him round, and we agreed he’d drive for us in 1984 – for $50,000! I told Player’s we had the dream team: Elio, quick, responsible, experienced, and this brilliant Brazilian newcomer who was going to be very, very good. But Player’s said we had to keep Mansell, because of their British interests and the fact that the British press always followed him. I was furious. I said to Player’s, ‘If you insist we keep Mansell, I’m not paying for him.’ So Player’s paid Mansell’s salary. Senna went off to Toleman for his first F1 season, and a year later I had him sitting in my office again and signed him for 1985. But this time it cost me $585,000.

“Ayrton was wonderful to work with. In the workshop he had an uplifting effect on everybody. He made a lot of demands, but you could see most of them had merit. He was like Jimmy, like Jochen, like Ronnie: if he wasn’t on pole there was something wrong. Everybody loved him, and would do anything for him. If you have an Ayrton it starts to look as though he’s running the show, but it’s what the team wants.

“When Elio left at the end of 1985 I called Ayrton and said, ‘Good news, I’ve signed Derek Warwick.’ He didn’t say anything immediately, but next day he called back and said, ‘I’m not prepared to agree to that.’ Ayrton dominated his team-mates, intimidated them, and he knew Warwick was strong, and he didn’t like it.

“He was ruthlessly single-minded. Where our relationship came a bit unstuck was when he said, ‘You’ve got to get Honda engines for ’87. If you don’t, I won’t drive for you.’ We had an ongoing contract with Renault, but when you’ve got an Ayrton you’re prepared to compromise almost anything to keep him. So I got Honda engines – had to take Satoru Nakajima as No2, as part of the deal – and then I had to tell Renault. One of the shittiest things I had to do in my career was welsh on my deal with Renault.

“In August, sitting in a hotel at Hockenheim, I drew up a new heads of agreement with Ayrton for 1987. But I needed more funds to give Ayrton the development programme he wanted. I tried to get more from Player’s, who were only paying us $2.5 million a season, and I also approached British American Tobacco, who marketed the JPS brand outside the UK. No go. So we did a deal with R J Reynolds to run the cars in Camel livery, $7 million a year for three years.

“But, because one of the clauses in the simple heads of agreement said the team would be sponsored by Player’s, Ayrton came back from Brazil in December and said I’d broken our agreement because we were now with Camel – never mind that it was at nearly three times the money, which would benefit the car he’d drive. We had to negotiate all over again, and the upshot was I had to give him $5 million for two years, with an option to leave after a year. He’d scuppered us, because all the extra money I’d raised from Camel to spend on the cars had to be paid to Ayrton. And then he exercised his option at the end of 1987 and went to McLaren.

“As soon as I found out from Honda that he was going, I thought, I’m not going to be caught sitting on my arse here. There were very few drivers who were acceptable to Honda, and one of them was Nelson Piquet, so to keep our Honda engines I got together with Camel and we signed him. He was past his best by then: his motivation wasn’t what it had been, because he’d become tainted by the huge sums of money he was earning, the yacht with the helicopter on deck and the jet-skis on the back. But I liked him enormously: great fun, with a wicked sense of mischief. He loved winding Ayrton up, of course, calling him the São Paulo taxi driver, implying to the press that Ayrton was gay – which, I can tell you, he most certainly wasn’t.”

In July 1989 Peter’s long career with Lotus came to an abrupt end. “We were working on good sponsorship deals for 1990 – one with Coca Cola, another with BP – when suddenly [Lotus finance director] Fred Bushell was arrested over the DeLorean affair. Not surprisingly, Coca Cola and BP both withdrew at once. I went to Hazel Chapman and said, ‘I’m sorry, but I don’t think I can keep working under these circumstances.’ I left the following week.”

Peter did a year on the other side of the F1 fence as a permanent FIA steward, and spent a couple of years with the BRDC. Then he retired. “Through working too hard I had missed my own children growing up, and I didn’t want to make the same mistake with my grandchildren.”

Our lunch has barely scratched the surface of Peter’s F1 life. As he drives me to the airport, there’s more: the endless argumentative FOCA meetings, with Bernie sitting quietly, knowingly, in the corner. So many more Lotus stories: the twin-chassis 88, which was banned. The turbine 56B. The four-wheel-drive 63. The wild ideas, the dramas, the arguments. The characters whose paths crossed with Lotus, from Keith Duckworth to David Thieme, and the designers, from Len Terry to Gérard Ducarouge. The other drivers: Arundell and Spence, Nilsson and Dumfries, Henton and Crawford.

But Peter reserves his deepest affection for the mechanics, the Lotus people who worked so hard, with indomitable resilience and good humour, celebrating the good times, coping with the bad. “Bob Dance, Eddie Dennis, Nigel Stepney, and generations more, right down to Bob the Broom, who swept the floors: he wasn’t very bright, but he had the heart of a lion. It was a huge privilege to work with those blokes, and live through it all. I had a hobby which became my job, and then my entire life. That makes me a very fortunate human being.”