Pryce crashed the Lola in his first ever ‘public-race’ qualifying session, but got it rebuilt and was winning minor FFord races by the end of the year. He then got hooked up with Royale in 1971. Aboard the RP4 of TAS Racing, he won the Formula F100 title for 1300cc sports-racing cars. He also drove works Royales in Formula Super Vee and then, by the end of the year, Formula Three.

But it was in the F3 race at the Race of Champions meeting in March 1972 where Pryce really came to prominence. He dominated this Brands race, taking the RP11 to a 15-second victory. Bob King, the boss of Royale at the time, recalls: “We had a borrowed engine, a ‘cooking’ Vegantune which we’d got for that race. They stripped the car down afterwards. They thought we had a bent engine, they thought we were underweight. But they pulled it apart and found it all legal and that Tom was just someone who was extremely quick.”

Pryce, though, was still rough around the edges. “It took him a long time to learn that if you tuck your nose in right behind someone you’re going to come off in the turbulence,” says King. “He just drove the car. He had no idea when he started how to set a car up and we had to teach him about gear ratios and hone him. But I was very fond of him — he was like a little brother.”

The first major accident of Pryce’s career was not his fault, though. In qualifying for the ’72 Monaco F3 race, his Royale coasted to a halt before Casino Square. He was trying to fix the car when Peter Lamplough came round the corner, locked up and bowled Tom into a shop front, breaking his leg. He returned by the end of the year, but by now Royale was focusing on Formula Atlantic. That paid dividends early in ’73, when Pryce won three early-season races.

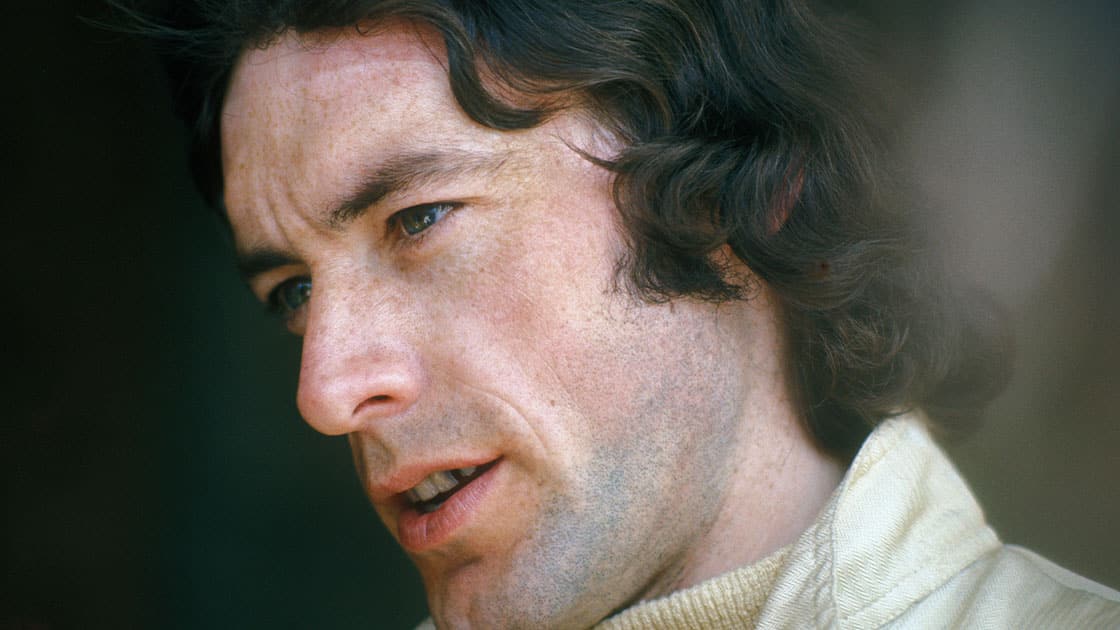

Peterson-esque car control abilities were evident early on

Grand Prix Photo

Then came the move to Formula Two. At mid-season, with backing from racer and property developer Chris Meek, Pryce got a seat in Ron Dennis’s Rondel Motul team. His best day came at the Norisring, where he took second behind team-mate Tim Schenken. The Welshman had been leading, but a brake problem dropped him behind the Australian.

Rondel had planned an F1 effort for ’74, but Motul took its sponsorship to BRM when the car was half-completed. Designer Ray Jessop then called up Pryce and asked him to sound out Meek about backing the team. Eventually Jessop himself tracked down Meek and he, plus Rondel backers Tony Vlassopulo and Ken Grob, revived the project as Token (Tony/Ken — geddit?). The car just made it to the International Trophy, where Pryce managed four laps in qualifying. In the race he did a sound job on his F1 debut, but went out with gear-linkage failure.