“Through 1955-56 we made many experiments. We did a completely new-design tubular frame to improve chassis stiffness, using more tubes, smaller tubes, and changed brake drums — though we never had any problem with them. We fitted two fuel pumps, one on the engine, one on the gearbox. I did big work on streamlining the exhausts, sometimes one pipe, sometimes two; we had a little trouble in the aluminium-steel multi-plate clutch, which was corrected, and so on.

“I experimented with fuel injection, beginning alone without any help. All my designs were my own: I never copied from anyone, so I alone was responsible for my mistakes. I had to learn as I went along.

“We made our own quarter-engine-speed injection pump and started with injection direct into the inlet valve, later onto the exhaust valve — this was very difficult especially since I was alone in Italy with this work. We worked day and night, terribly hard, and found more power with injection, but better response is so hard to measure. In fact the power curve was too sharp, the power came in too hard and made the car difficult to control as the cornering power of the tyres of the time was really very small.” He laughed, dark eyes twinkling under beetle brows: “At Goodwood, Moss drove the injection car with 265bhp. I remember he tried his own carburettor car with 240-245bhp and the times were almost the same. Injection gave us big power for the time, but was difficult to utilise.

“At Reims we ran our streamlined 250F — that was my idea. We always tried to improve the aerodynamics of the car and I did small model tests of the streamliner in the Milan University wind-tunnel. The full-size car was not very good, but was the best of the type, I think — better than Ferrari’s!” Cue laughter.

In search of reliability Maserati’s works team applied a rigid ‘lifing’ programme, changing con-rods after two or three races, the valves after every race, valve finger gear after so many hours, pistons too.

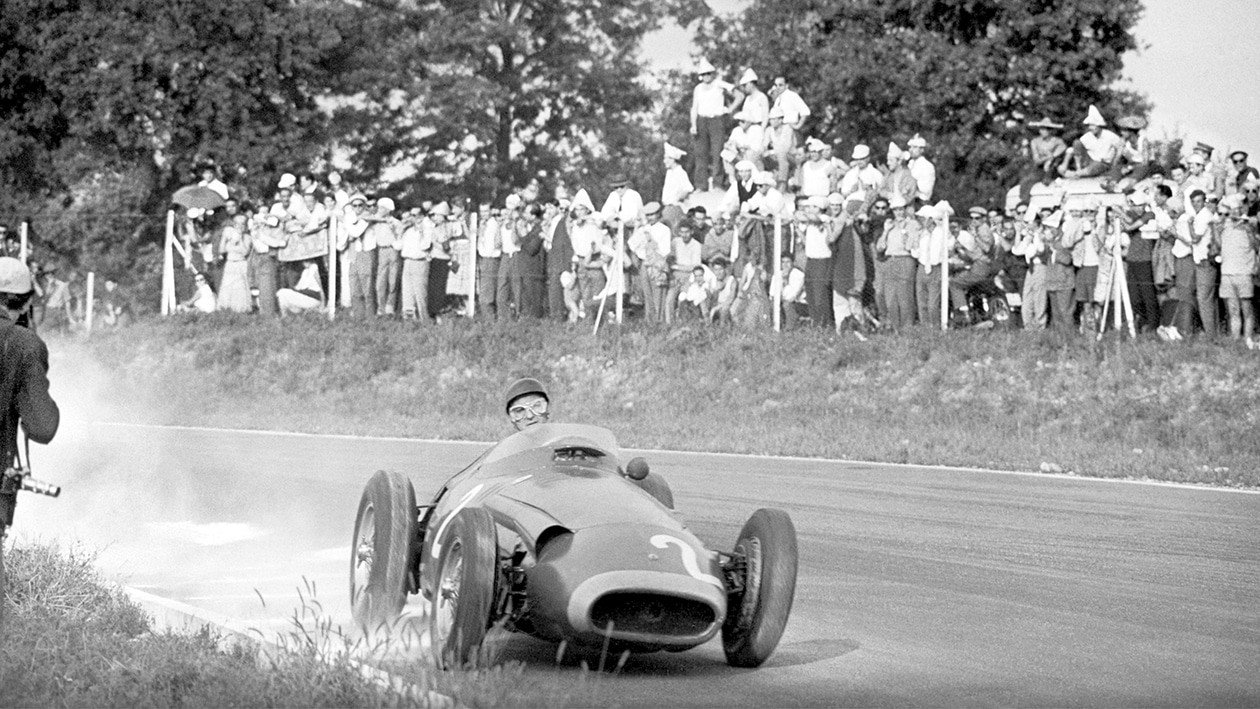

Harry Schell at Rouen in’ 57

Grand prix Photo

But Alfieri, a sensitive deep thinker, had witnessed the aftermath of works driver Onofre Marimón’s fatal accident at the Nürburgring in 1954 and never saw a race thereafter. He would work on the cars during practice but leave for home at 11 o’clock on race morning: “It’s a big responsibility as chief engineer, and for me to watch our drivers racing was only a great suffering.”

He experimented with disc brakes — “We fitted an English set but we were too far from Dunlop, Lockheed et cetera to be confident, and the result was not so much better than our own drum brakes anyway” — and in 1956 he built the ‘offset’ 250Fs for the Italian GP, design and construction occupying barely one month.

“At Reims I saw our cars were too slow, and I came back as passenger in a Fiat 1100 driven by Bertocchi and thought, during the voyage, ‘What can I do?’ And when we arrived back in Modena I said we shall do a new chassis, a new gearbox with an offset drive-line and a new lower body with offset cockpit and driver seated down beside the propshaft, and it was all ready for Moss to win our Italian Grand Prix at Monza that September.”

Alfieri allowed himself a rare smile at that memory, before explaining developments for 1957 — when Maserati at last won a World Championship:

Fangio en route to winning the 1957 Monaco GP

DPPI

“Each year we had done new cars; the 1956 Fuoricentro (offset) showed good speed but not very good handling and we could not understand why. The technological language of the time was inadequate for our drivers to explain what was happening in the cars, and so we started again with the new lightweight design for ’57; even smaller tubes, more of them, 40 per cent stiffer for the complete chassis and with increased weight bias to the rear, maybe 48:52 distribution dry.

“Mr Botasso, engineer of Pirelli, was a very nice man, a great friend of mine. So as not to hurt Maserati, when Pirelli decided to stop racing in 1956 they made many, many tyres for us to use in 1957. The problem in tyres then was not compounds and grip, it was only safety, to last a 500km grand prix distance carrying a heavy car without exploding.