“But that was in the dry. In the wet, on occasion I would simply drop the clutch at a slow corner and roll round it. That was the only way to do it. Even the slightest whiff of throttle would cause wheelspin.

“The problems in the dry were that the car was very heavy to drive and hot. That’s when I realised how tough and strong Denny was. I could keep up with him for the first 100 miles or so, but I struggled in the second 100 miles and he would gradually pull away. The worst race was at Road Atlanta in the Deep South; it was incredibly hot and humid. I was leading when I broke down near the end, and the marshals literally had to lift me out.”

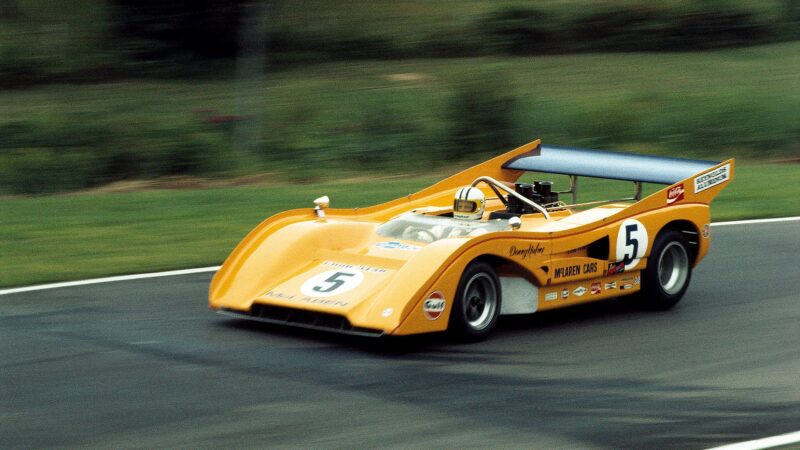

1971 Can-Am champ Peter Revson en route to the Laguna Seca race win in the McLaren M8F

John Lamm/The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images

He’s right. We’re just rumbling around for photographs — simply resting your foot on the throttle in second gear is good enough for 60mph — but already the BTUs from the front-mounted radiator are wafting up through the cockpit, while the Chevy’s ‘killer’ joules are percolating nicely through the thin, reclining metal bulkhead that separates me from it. The steering is a bit bicep-curly, too — and that’s without downforce exerting its unseen hand.

A dry line is forming. Slowly. It’s wide enough for most cars, but not the M8F. It’s desperate to go, though. Keener than I am. And a lot keener than its understandably fretful owner. It’s frustrating — who wouldn’t want to gorge on the fattest power curve ever? — but on this occasion discretion wins over what little valour I have. When far more experienced pilots raised their eyebrows as I explained what I was about to do, and then advised a slight settling lift before the gentle crest on the approach to the chicane on Donington’s short circuit, I knew for sure that this car is beyond the extraordinary.

It feels lovely though. Once you have slithered your legs under a flat-bottomed dash (that reminds me of a guillotine), you’re closeted, hips hugged by one of the tub’s aluminium box-sections and the cockpit’s central stiffener, knees braced behind back of dash. You sit low — Gethin used to “disappear” — and you can just make out the wing tops for placement purposes. It suddenly seems a lot smaller than it had appeared from the outside. But that doesn’t mean to say it’s not wide. As engine sizes grew in Cam-Am — McLaren would eventually use a liner-less alloy-block 9.3-litre in qualifying — so too did tyre widths. The title-winning M6A of 1967 featured 13.5in rear boots; M8F is on 17in. Today, of course, this is hardly a plus. But again you get the feeling that if you’re ultra-smooth, this car will work with you. Not frighten you too much.

“You didn’t chuck them about,” says Gethin. “It paid to be neat and tidy. It was difficult on cold tyres — I went off on my first-ever lap in the car — and once they were up to temperature you had to look after them. You couldn’t drive them sideways; you needed to keep the air running along the length of the bodywork to get the downforce. Lose that and you were off.