Disliked, too. Riccardo was one of those young drivers very quick from the outset, and often drove over his head in those early days. But what affected him more than anything was the accident at Monza in 1978, which cost the life of Ronnie Peterson.

Other drivers judged Patrese culpable for the chain-reaction disaster, which occurred within seconds of the start. It seemed not to matter that the blame lay plainly elsewhere: this upstart was a natural whipping boy, who needed to be taught a lesson. If Patrese’s entry for the next race, at Watkins Glen, was accepted, they said, they wouldn’t take part. Thus they effectively had him banned for a race.

“It was because they didn’t like my attitude over the season, but by timing it when they did, it looked as if they were punishing me for the Monza accident. Psychologically, I had no problem with that, because I knew it hadn’t been my fault But it took a long time to forget how the other drivers treated me.”

Many years on, one of them told me that this was the only incident in his career of which he felt truly ashamed. It had been a witch-hunt, nothing more or less, and one of the loudest voices, sad to say, was that of James Hunt. To the end of Hunt’s life, the rift between himself and Patrese was never healed.

A karting world champion in 1974, Riccardo came into F1, via F3, with Shadow in 1977, and spent years — too many of them — with Arrows, then as now a fringe team. Bernie Ecclestone was always a fan, and tried to get him to Brabham in 1979, but Patrese was starry-eyed about Ferrari, and declined to sign long contracts, so as to be free to accept the offer, which was constantly promised, but ultimately never delivered.

In 1982, finally, he committed to Brabham, scoring his first Grand Prix win, at Monaco, and his second, at Kyalami, the following year. For ’84, though, Ecclestone unfathomably replaced him with the overrated Teo Fabi, and Riccardo, against his better judgement, signed for the Euroracing Alfa Romeo team. Two seasons in the deep wilderness followed.

Patrese always tolerated Mansell’s excesses with admirable fortitude.

“The cars were hopeless, and I was so angry about it that, by 1985, it was beginning to affect my private life. I can remember one day saying to myself, ‘Hey, Riccardo, you have to do something’. I mean, I was not smiling at all! I was a turning point I changed my approach, my mentality, everything — I still don’t know how l did it. After that, life became easier.”

Ecclestone has been really close to very few drivers, but Patrese was one of them, and so he went back to Brabham for two more years.

“It was lucky for me that Bernie and I were friends. When he decided to give up being a team boss in 1987, he recommended me to Frank Williams.”

This was to be the most productive relationship of Riccardo’s career.

“When I went to Williams,” he said, “it was like a camera which had finally come into focus.” Soon everyone in the team became very fond of him, not least because of his excellent rapport with Patrick Head — not least, either, because he was much easier to live with than Nigel Mansell, who returned to Williams in 1991. Rather more of a team player, too.

“You’d call Riccardo up,” said Head, “ask him to test at a moment’s notice, and he’d say, ‘Fine. No problem. I’ll be there’. He’s not a selfish man, that’s the point, which is quite rare in a racing driver. His ego’s under control, too. Which is also quite rare.”

Speaking of egos, in 1991 Mansell said this: “I take Riccardo’s speed this year as a great compliment to me.” Er, how so? “Well, because I’m the only one who can motivate him.” Had Patrese been inclined to return the back-handed compliment, he might have suggested that perhaps Mansell had overdone the motivation: it was not until Silverstone, after all, that the great man managed to out-qualify him.

As it was, Patrese always tolerated Mansell’s excesses with admirable fortitude. And although the Williams-Renaults were not conspicuously reliable in 1991, Riccardo had a very fine season, with four pole positions and a couple of victories.

While not on the same page, week in, week out, as Senna or Prost, when the mood was on him Patrese was a magnificent racing driver, and my abiding memory of him is in final qualifying at Estoril that year.

Early in the session his own car blew up, and his behaviour was pure Latin theatrical as he stomped back to the pits. There the spare Williams sat but, under the terms of Mansell’s contract, it was for his use alone. Not until the last five minutes, when it was clear that Nigel would not need it, was Riccardo permitted to climb aboard.

There had been no opportunity for set-up work, and the Renault V10 was of an earlier specification, but Patrese had ire and adrenalin to spare; after a single warm-up lap, he shoved Senna, Berger and Mansell aside, and put himself on pole. He won the next day, too.

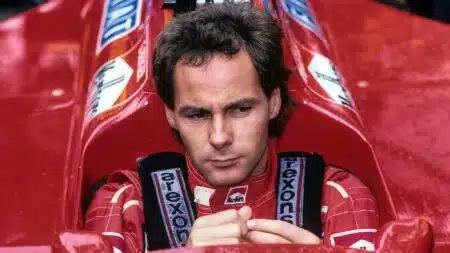

Patrese started from pole for the 1991 San Marino GP

Getty Images

Williams went ‘active’ for 1992, and although their performance advantage was enormous, Patrese was less at ease, and rarely now on terms with Mansell.

“I admit I prefer passive cars,” he said, “because they have so much more feel. Nigel either has more bravery, or less imagination, or both.”

He finished second to Mansell in the world championship, and then left for Benetton, with whom he had signed when it seemed that Frank would run Prost and Mansell in ’93. Almost immediately, Riccardo learned that Mansell was quitting F1, that he could have stayed after all.

“That’s life, isn’t it?” he shrugged. “Two weeks after I had signed with Benetton, there was a chance for me to stay with Williams, but I said, ‘No, Riccardo, if you’ve signed something — even given your word — that’s if.”