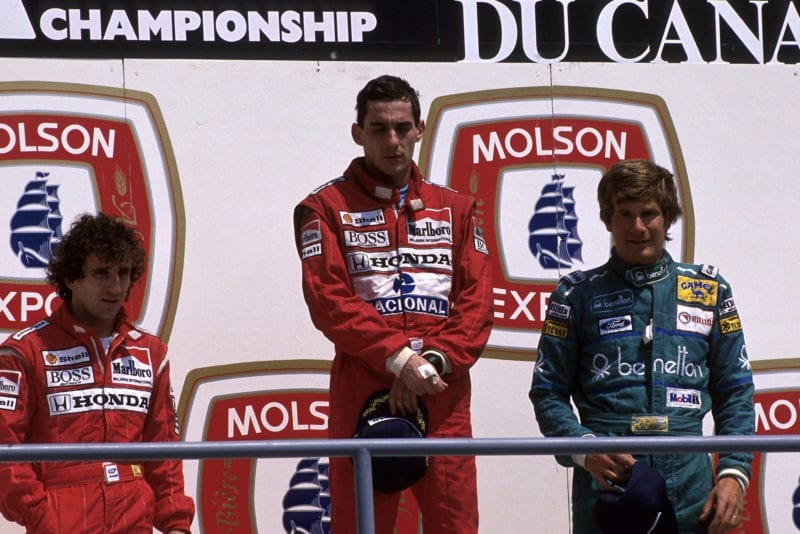

1988 Canadian Grand Prix race report

Aytron Senna took the win for McLaren

Motorsport Images

Montreal, June 12

The Canadian Grand Prix was cancelled last year, mainly due to a dispute between the two big Canadian breweries, Labatt and Molson, as to who should sponsor the event. The decision finally went to Molson’s Breweries, but only after the closing date for FIA/FISA acceptance, and in addition to this big-business wrangle there was also the question of the pits and paddock arrangements being totally outdated for Formula One. It was like the inadequacies of Monte Carlo, but so far no-one has been brave enough to penalise the Principality.

With Molson’s financial backing and the support of the City of Montreal, the organisers built an entirely new pit-lane, garages, control tower, grandstands and all the rest of the required paraphernalia to cope with a World Championship Formula One event. The new position was at the opposite end of the island circuit, and it was all achieved within fifty days of receiving the building permit from the City Council — a remarkable achievement. Though the detail work was not complete when practice started on Friday morning, and although some of the expected “creature comforts” were a bit primitive, the new layout was workable.

All the cars and material had travelled from Mexico City to Montreal by road in a vast convoy of hired trucks and trailers, a mammoth job organised by FOCA. The omission of the Canadian race from the 1987 calendar meant that many competitors were making their first visit to the circuit of Gilles Villeneuve on Notre Dame Island in the St Lawrence river, and many drivers were seen doing a lap of the 4.39-kilometre circuit on foot the day before practice began. A typical example of a team with no prior knowledge of Montreal and its circuit was March, of whom only three members of the entire personnel had ever been to Canada before — a built-in handicap it could do nothing about.

Apart from some hair-raising accidents, luckily without any personal injury, testing and qualifying ran more or less to plan, starting a bit late on Friday morning due to some “pfaffing about” by the organisers which caused FISA to inflict upon them a $10,000 fine.

The two McLaren-Hondas were their usual dominant selves and, not unexpectedly, Senna ruled the roost. Alain Prost was only a fraction away, but that fraction meant second place to the Brazilian’s pole position, his fifth this year. The Ferraris were close behind, but behind nonetheless, and the two Benettons were going, well, their factory Cosworth-Ford DFR engines being visibly more powerful than the V8 Judd engines and the production Cosworth DFZ engines.

More or less flat, the long and thin island circuit has one side a bit wiggly and the other side very fast. It was at the end of this fast leg that the new pits were built, with a dauntingly fast right/left swerve to take the circuit along the other side of the pit-lane wall.

Ferrari’s Gerhard Berger started 3rd

Motorsport Images

The approach to this swerve was over 185 mph, the change of direction only losing about 5 mph for the faster cars, and it made a few drivers suck their teeth and concentrate. It was spectacular for those watching from the pit-wall as well. The high-speed merchants were flat in sixth gear to the 50-metre marker board; a quick lift off the accelerator pedal and then it was hard down and into the right-hander. Not for the faint of heart, even if you were only spectating.

Both qualifying hours were punctuated by cars spinning off around the circuit and there seemed to be too few “parking places” for abandoned cars, so qualifying was stopped with the red flag, and the time lost was added to the original hour.

More often than not it seemed to be a EuroBrun which spun and held things up, but on Saturday afternoon Derek Warwick spun backwards, and mostly airborne, through the pits ess-bend in the Arrows T-car and hit the outside retaining wall a nasty thump. He was very lucky to get away with bruising and a shaking.

In the dying minutes of qualifying, Prost went out for a final thrust at Senna’s pole-position time, set up early in the session, but just failed to beat it. His Honda engine had been blowing off the FIA boost control-valve, and though this was changed all was not 100% with the engine.

The Williams-Judd cars were just not on the pace, in spite of all their Hi-Tech, made all the more embarrassing by Philippe Streiff splitting the Didcot cars with his decidedly Low-Tech AGS from the tiny French village of Gonfaron, and with only Cosworth DFZ power available.

The starting grid had one or two interesting aspects, such as Stefano Modena in fifteenth position on his first visit to the Canadian circuit, and Ivan Capelli (with the same handicap) just ahead of him. In spite of Honda power, Nakajima just could not get the feel of the high-speed part of the circuit, but Alessandro Nannini being up near the front with the Benetton is no longer a surprise; it is now expected, regardless of the circuit, because the lad is good. Unlucky was Frenchman Yannick Dalmas, who normally qualifies his Lola with ease; a morning accident involved a lot of rectifying work before final qualifying, and time ran out before he could record a sensible lap time, so he had to join the DNQs.

The two practice days had been a his on the cool side, but Sunday was much more summer-like, and the only worry for the turbocharged cars was fuel consumption. The measly 150 litres they are allowed this year means that racing has to be conducted at an economy setting, the fuel read-out on the digital instrument board being the driver’s only real concern. The non-turbo 31/2-litre cars have no such restriction and can run flat-out, providing the engines will take it, and the works Benetton-Cosworth/Fords went to the grid with 215 litres of fuel on board. On the grid the McLarens had their fuel tanks covered with sheets of heat-resistant aluminium foil while they sat in the hot sunshine, an indication that the tanks had 150.00 litres in them with no room for expansion.

By all normal circuit standards, the grid was laid out the wrong way round, with pole position on the right, presumably because on a circuit diagram there is a right-hand curve immediately after the start. In fact, this curve is “straight-lined” on the racing line into the braking area for a sharp left-hander.

Alain Prost leads at the start

Motorsport Images

Pole position is supposed to give you three important advantages: (a) more starting money than anyone else, (b) a seven-metre start over the number two position, and (c) the best line into the first comer. Senna had (a) and (b) but not (c), and Prost made the most of the situation. It was a good, clean and trouble-free start, and the two McLarens were wheel to wheel, heading for the apex of the left-hander, with Prost sitting it out on the inside line, and winning. The two red and white cars were away, with only themselves to beat and no-one to trouble them.

Their progress was majestic. I was going to say they dealt with all the opposition in a devastating manner, but the truth is there was no opposition.

For a few laps the Ferraris and Benettons could watch the McLarens disappear, but that was all. The only time the Lotus-Hondas saw the McLarens was when they came up in the mirrors to lap them, and then went by and disappeared. Most of the opposition, if you can call it that, wilted under the strain. Nannini’s Benetton’s engine died when the fuel pressure disappeared, both Ferraris dropped out, the Williams pair were hardly in the race and their Judd engines failed before half distance, and the rest just tried to keep going and not get in the way of the Woking duo. Most drivers managed to keep out of the way when being lapped, except Palmer who seemed unaware of Prost bearing down on him.

Thierry Boutsen got himself onto the podium with 3rd

Motorsport Images

Prost led for the first 18 laps, but then Senna closed on him and forced his way by into the hairpin at the eastern end of the circuit and it was all over. The Brazilian demonstrated beautifully his uncanny skill at overtaking slower cars with the minimum of fuss or delay, keeping Prost at arm’s length as they both drove as fast as their fuel-consumption situation would allow.

As the race wore on, and more rubber was laid on the surface, the circuit got quicker for the same effort, so their lap times became lower and lower without any strain, and they traded fastest laps for the revised circuit. Five laps before the finish they both eased off and cruised home at a speed that was still faster than most drivers’ best laps.

As soon as the two McLarens crossed the finish line they pulled off to the side and stopped, the drivers’ unemotional expressions not letting on about how much fuel they had left in their tanks. They could either have been about to run dry or they could have had enough fuel for another lap, or even two, but that is a “trade-secret” belonging to Honda and McLaren and they left the opposition, whoever that might be, wondering.

The only comment Prost made afterwards was that his brakes were not completely to his liking, and that his water temperature was higher than desirable, possibly due to something slightly blocking a radiator intake. But there was no suggestion that these things prevented him from winning — there was only one thing that did that, and that was Ayrton Senna.

A very satisfied Thierry Boutsen was the only driver to stay on the same lap as the McLaren pair, and he had simply done the best he could with a car that was faultless, apart from not having the power in 3 1/2-litres of normally-aspirated engine to match turbocharged 1 1/2 litres, even when the latter were held down to a lot less than 2.5-bar and with the engine-management programmed for maximum economy. While racing this year is a shadow of the exciting days of unrestricted fuel-consumption and demon tyres (when teams perfected ten-second pit stops and team mechanics were as important to victory as were drivers), it has now become highly sophisticated and clinically efficient, with average speeds ever rising.

Senna closed the gap points gap to Prost with the win

Motorsport Images

The return of the Canadian Grand Prix was welcomed by everyone, and for most people vvorking in Formula One the visit to Montreal softens the blow of the United States Grand Prix at Detroit the following weekend. Of especial interest to those following the Drivers’ World Championship, the Canadian race was the fifth in the 1988 sixteen-race series. As the rules state that a driver can only count the points scored from eleven of the races, it means that the McLaren Championship is only just about to start, unless Berger (Ferrari), Boutsen (Benetton) or Piquet (Lotus) upsets the apple-cart by winning a race.

These first five races, all won by the McI.aren drivers (Prost three, Senna two), have really only been a “warm-up”. From now on it could get serious. DSJ