Chapman was at the meeting watching his Lotus 18s win the F1, F2 and FJ races. “Colin said he’d still like me to drive for him — if I bought a car. I had no money so we agreed he’d lend me a car, which would be entered by Team Lotus though I was to prepare it and pay for spares, and at the end of the season, I’d sell it and pay him the purchase price, with interest. Part of the deal was that I had to drive to team orders and was the recognised third man behind Jimmy Clark and Trevor Taylor. That was frustrating because I reckoned that, in equal cars, I could beat Jimmy and would beat Trevor but, driving to orders, you can never be sure.”

In Formula Junior that year, Arundell never finished below fourth. He also took in three sports car races with the Gilby-Climax (see last month’s Motor Sport) and performed superbly, and he began to feel that his relationship with Chapman was not all it might be.

“Colin had almost a love affair going with Jimmy. He spent the bulk of his time with him, had a few words for Trevor and me he almost completely ignored. I was getting pretty cheesed off about it. As we sat on the grid for the last race of the year, at Brands Hatch, he talked to both Jimmy and Trevor but didn’t come near me. It seemed that I might be out of a drive for 1961.

“That got to me and I decided to forget team orders and win, so I did. Trevor’s gearbox went on the line and I beat Jimmy fair and square. I then had to sell my car to pay back Colin and, advertised as the ‘Clark beater’, it made me a fair profit. Colin was not amused by that, but he got his own back.” As we shall see.

Chapman and Arundell relationship was strained – here they are talking at Goodwood ’64

Getty Images

In 1961, Clark was committed to F1 and so Arundell moved up a rung, as number two to Taylor. Peter prepared the car himself, though Lotus supplied the spares, and had to drive for second place when Taylor was present.

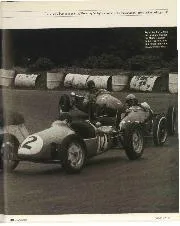

“By this time, there were FJ races going on all over the place and Trevor and I would often go off to separate meetings, both of us winning on the same day. Consequently I began to get quite well known on the Continent, though less so here. The fact that Trevor and I had to drive to orders didn’t affect us off the track, we got on very well together, but it was still frustrating. Then came a race at Silverstone which was run in two heats with times deciding the final placings. Colin wasn’t there, Trevor and I were in separate heats, and Mike Costin whispered in my ear. We both won our heats but I won overall, fifteen seconds clear of Trevor.”

In 1961, Arundell carried off four International FJ wins as well as a lot of lesser events and it’s as well to recall that FJ was then the only European single seater category apart from F1. Among those wins was the Monaco GP support race which Taylor had led until retiring. Because of team orders, we shall never know whether Arundell might have won more.

Two incidents from that year, both involving crashes, shed some light on the man. In the first, at Mallory Park, a club driver had crashed, his car had caught fire, and Arundell pulled him out, unquestionably saving his life. “I don’t remember the details, I just happened to be the man nearest to the crash. Don’t worry about it.” The second was at the Nürburgring 1000 kms when his Elite came off the track, plunged down the side of a mountain, being slowed by the tops of the trees, and finished up in fragments several hundred feet below the circuit. “The blood side of the sport is not on, you can’t talk about a man making a mistake and dying for it. I am not a brave man and I wanted crash barriers everywhere but Jimmy and Stirling would have none of it. They’d say, ‘It separates the men from the boys.’ Well, I was at St Mary’s at Goodwood when Stirling had the crash which ended his career and I’m convinced that had there been barriers there he would not have been so badly hurt.”

Arundell felt Clark got preferential treatment from Chapman

Getty Images

1962 was Arundell’s year. Taylor had moved up to the F1 team alongside Clark and Arundell was number one in the FJ team. From 26 starts, the Arundell / Lotus 22 combination took 18 wins (12 of them in International races), including a second victory at Monaco, four seconds (never more than 1.6 seconds in arrears) and four retirements. It was a season to remember, not only in terms of success but also two famous stories. At Goodwood, while shaking down the first Lotus 22, both Arundell and Clark complained about the car so Chapman said a few rude words, jumped in, and was quicker than both! That is the story which has entered motor racing folk lore. Peter remembers it differently, “Chapman had pulled that stunt several times before, and at Goodwood he was quickest at that point. But I got back in the car and took a second off his time and that was the last time Colin ever drove a racing car though, later, I pleaded with him to drive the Lotus 27.”

The second story concerns the famous wager at Monza. Some German drivers who had been running illegal engines could not believe the speed of the works Lotuses and assumed they, too, were bent. The journalist, Richard von Frankenberg, took up the story and splashed it in the German popular press. “Colin was prepared to let the matter fade away but I told him to issue a £500 challenge, and I would put up half, Von Frankenberg would have to accept.

“Colin was still sceptical but I knew that since a lot of our races took place on street circuits, the only tracks available for the challenge were Zandvoort and Monza and, since I’d had problems at both, my winning speeds had not been as fast as I could go. Colin saw the logic, put up £1,000 himself and promised me half of the winnings if I pulled it off. Von Frankenberg nominated Monza, the bet being that I should go faster than in the race. I did so, the engine was stripped and proved legal and Colin paid me my £500.”

The incident is recorded in detail in Doug Nye’s The Story of Lotus, 1961-71, von Frankenberg ate crow and the story made headlines around the world.

For 1963, Chapman produced the Lotus 27 FJ car which had a fibreglass monocoque. “They’d done all the usual tests for torsional stiffness but, under braking, the front suspension would pinch in the monocoque — you could watch it happen.