F1’s kiwi conveyor belt of talent

Liam Lawson is the latest ace to emerge from New Zealand, a nation with a proud tradition of churning out top-level drivers. Jack Barlow reveals the winning formula

Getty Images / Red Bull Content Pool

New Zealand is fairly small. It’s also very far away. But, right now, its racing drivers are having a moment. Often overshadowed by its larger neighbour ‘across the ditch’, the South Pacific country’s drivers can be found at the sharp end of many major racing series across the world.

Look at Liam Lawson, for instance, patiently waiting to pounce into one of Formula 1’s most desirable seats. Scott Dixon, Scott McLaughlin and Marcus Armstrong in IndyCar. Jaguar Formula E team-mates Mitch Evans and Nick Cassidy, whose title challenges came right down to the wire. And the startling Shane van Gisbergen, a versatile, generational talent who’s making significant waves in both NASCAR and its Xfinity series.

That’s just the tip of the antipodean iceberg. It begs the question: why are so many Kiwis doing so well? And why now?

Liam Lawson had a five-race stint with Alpha Tauri in 2023, finishing ninth under the lights in Singapore – his best outing of the season

Bruce McLaren, Chris Amon, Denny Hulme, Howden Ganley… they all embarked on the long journey to Europe and made their mark, in an era when Formula 1 stars loved nothing more than travelling the other way for the halcyon days of the Tasman Series. But from the mid-70s on, only several appearances by the supremely talented, if enigmatic, Mike Thackwell in the 1980s marked the sum total of New Zealand’s F1 presence until well into the new millennium.

The death of McLaren was a major factor, followed by the ever-swelling cost of entering Europe’s major categories. Few drivers had the financial backers or obvious pathways – there was the odd exception – and the stream of talent to the European top flight became a trickle.

Regardless of its drivers’ performances internationally, one thing remained stable: the country’s own vibrant racing scene. Karting competitions that were affordable proliferated and Formula Vee (now Formula First) and Formula Ford proved a relatively accessible avenue to advance through the local ranks. Away from the country’s complex, twisting circuits, from the 1960s rallying emerged as a force and began to increase in popularity. It all added up to a healthy, supportive grassroots environment for encouraging new talent, even if that talent didn’t have a whole lot of easily available, non-Australian overseas options to head to.

Scott Dixon is a six-time IndyCar champion.

Joe Skibinski

Greg Murphy’s early days on the track were focused on pure speed. For the New Zealand Grand Prix and four-time Bathurst 1000 winner, the notion of making a career of the sport he loved didn’t really come up. “The sport was very popular, but there was certainly not the thought process around being professional race car drivers back then,” he said. “There were a few … what you would call close-to-factory organisations, but it was all amateur after that. So even though we were racing in the top echelon of the sport, it wasn’t professional, it was amateur. There weren’t really opportunities.”

Murphy’s career took off after winning a Shell Ultra Formula Ford scholarship in 1990. Without it, he said, his career likely wouldn’t have gone far. “It basically gave me a free season racing Formula Ford in the New Zealand Formula Ford Championship, and without that there was no chance that I was ever going to get into car racing,” he said. “We just didn’t have the capacity. You’ve got to remember that in the ’80s it was purely, purely enjoyment. There was no seriousness to it. It was just a community of like-minded people going to enjoy themselves and race. There was no foreseen sort of pathway.”

Dixon’s fellow countryman Scott McLaughlin finished third in IndyCar’s 2024 final standings

A few years later, another precociously talented young driver would also find his way out of the country with the help of outside financial support. This time, however, it would change everything.

“Scott Dixon’s talent was apparent before he’d hit his teens”

Scott Dixon was clearly something special from the start. His talent was readily apparent before he’d even hit his teens – early on, he had a cushion strapped to his back to help him reach his pedals – and he quickly attracted attention from influential local backers. Mentored and supported by the evergreen Ken Smith, a remarkably quick driver who’s been a key figure in New Zealand racing since the 1950s, he soon exhausted the available options. His future was offshore, but the familiar problem of money loomed large. What to do?

Looking back, many point to Australia-born Dixon’s emergence as the beginning of a new era of opportunity for New Zealand’s drivers. Swooping in to help was a group of wealthy businessmen with a love of motor sport, no shortage of funds, and a plan.

New Zealand is blessed with a number of quality circuits, including Highlands Motorsport Park at Cromwell on the South Island

Getty Images

Most prominent of Dixon’s backers was Peter ‘PJ’ Johnston. Still a key figure in New Zealand motor sport – he was largely responsible for the World Rally Championship returning to the country in 2022 – Johnston recalls the plan to gather behind Dixon as something that simply had to be done.

“We had a lot of good drivers go into Australia, but getting into the international arena was a different thing,” Johnston recalls. “So we got a business plan and a structure around Scott and we funded his motor racing career into America. And that worked really, really well.”

The terms of the plan were fairly straightforward. In the manner of just about any investment, it was a risk: if Dixon was successful, he would pay his investors back. If not, well, so be it.

As anyone who’s followed American open-wheel racing even slightly over the past 20 or so years is aware, the bet worked out pretty nicely. Deciding to forgo Europe in favour of the more affordable and accessible United States – largely on the back of a successful post-season test with PacWest – Dixon quickly climbed through the ranks to end up in IndyCar, where he remains to this day. Still a leading competitor at the age of 44, he is one of American racing’s greatest drivers: a six-time IndyCar champion with 58 IndyCar race wins, an Indy 500 victory, and three Daytona 24 Hours wins.

Brendon Hartley was Red Bull’s reserve driver at 19

Money didn’t exactly flow freely in Dixon’s early years. Having to do it the hard way taught valuable lessons of its own, however, ranging from an expanded mechanical knowledge – he didn’t have a team of highly paid mechanics on hand – to bringing an added focus to the present. It was hard to think too far ahead when the money might run out at any moment, after all.

“Although it’s a small country [motor racing] is quite a popular sport in New Zealand,” he said. “But it’s not super-easy, it’s not just a given down there. I don’t know if it changes your mentality, of ‘maybe this is your last year, so you’ve got to make the most of it’, but that was pretty much every race. That was normal, you just took the ride for whatever it was. There was nothing set in stone… and there wasn’t really any structure until 1997, when we formed (investment group) Scott Dixon Motorsports.”

Beginning while Dixon was in Formula Holden, the group ended up with around 14 investors and ultimately took him to CART feeder series Indy Lights. Though it proved key to helping him into the top flight it didn’t always cover all the bases. When the odd unforeseen expense came up, as would inevitably happen, extra money was required to plug the gap.

“I destroyed a car in Milwaukee, I think it was, and the Giltraps actually had to stand in to buy another car,” he recalled. “Even then we were on a small budget. It was still kind of a slimmed down version to what you maybe see these days.”

Tony Quinn, left, has backed Kiwi drivers – here with Lawson.

Slimmed-down or not, the model proved wildly successful. There was no going back and, as more investors were drawn in, the opportunities for promising young drivers grew. The late Sir Colin Giltrap was especially prominent. The head of one of the country’s most well-known car dealerships, the Giltrap Group, he directed millions into many young up-and-comers. Just take a look at the current crop: with the odd exception, there’s a good chance you’ll find the black and white Giltrap Group logo plastered somewhere on their helmet.

“Post-Dixon, the number of drivers heading overseas exploded”

Post-Dixon, the number of drivers heading overseas exploded. Among the most notable were Brendon Hartley, who in 2017 became New Zealand’s first regular F1 entrant since Howden Ganley; Earl Bamber, a two-time Le Mans winner with Porsche; Wade Cunningham, who made it to IndyCar; the previously mentioned, Armstrong, van Gisbergen, McLaughlin, Evans and Cassidy; European Rally champion Hayden Paddon; and Richie Stanaway, who some say is perhaps the most naturally talented of all, as well as the greatest unfulfilled talent. That’s not counting the New Zealanders who have competed, or are currently competing, in everything from rallying to British F4, the Porsche Supercup to Australia’s Supercars.

These days New Zealand’s domestic support system stretches far beyond wealthy benefactors, important as they are. A host of scholarship and funding opportunities exist, including MotorSport New Zealand’s Elite MotorSport Academy and the Team Porsche New Zealand scholarship, the latter involving Bamber. Among the most prominent and influential organisations is the Tony Quinn Foundation, which supports Kiwi drivers from grassroots right up to the international level.

From left: Nick Tandy, New Zealander Earl Bamber and Nico Hülkenberg, Le Mans winners, 2015

It’s all come a long way from the days where taking away a weekend trophy or, at most, a drive in Australia, was the high point of ambition for most of the country’s competitors. While a career in motor sport is never easy, a close-knit network is on hand for New Zealanders who are willing – and quick enough.

So, is there something special in New Zealand’s water? The common consensus, even from the locals, is no. Instead, many point to factors including an ability to start young (drivers can obtain a MotorSport New Zealand competition licence at the age of 12), clear career pathways, a variety of relatively affordable domestic racing opportunities and a natural love of sport and the outdoors as the underlying reasons behind the country’s talent.

“The foundation’s always been there,” said Steve Horne, a high-profile figure in New Zealand motor sport perhaps most widely known for his success as a team manager in IndyCar. “To get offshore out of New Zealand is still very, very difficult financially, but there’s been a strong group of local supporters over the years. We’ve got really good local tracks that have evolved over the years. We race all through the year and we do a lot of winter racing. There are really good scholarships here. It appears to be an overnight sensation, but it’s not. It goes back a long way.”

“I think it goes right back to the grit and determination of being a wee country on the other side of the world,” said Tony Quinn, the influential force behind the Tony Quinn Foundation. “It’s part of their ethics and the way [New Zealanders have] been brought up. It all has an effect on how you go about things. I think right now – and, as far as I can see, into the future – the Kiwis are producing some bloody handy talent.”

Taupo was the only New Zealand circuit on the 2024 calendar of Supercars – the series in which Kiwi driver Shane van Gisbergen was champion in 2016, 2021 and ’22

There’s no shortage of categories the country’s young drivers can choose from. Following on from karting, Formula Ford and Formula First is the Formula Regional Oceania Championship, which includes the New Zealand Grand Prix. The series gives locals a chance to match up against top-line overseas talent, with recent entrants, under the previous Toyota Racing Series moniker, including Zhou Guanyu, Yuki Tsunoda, Franco Colapinto, Lance Stroll and Lando Norris. Stroll was champion in 2015; Norris, 2016; and local lad Lawson, 2019.

It’s not all open-wheel racing, either, with series like the 2K Cup, the Mazda Racing Series and the Toyota 86 Championship providing options for those more interested in racing with a roof over their heads.

Along with the various support systems and pathways, MotorSport New Zealand president Deborah Day points to the country’s challenging racing conditions as useful for helping hone talent. “I think, to be fair, it probably comes down to the style of motor sport we have down here,” she said. “We’re lucky enough to have seven circuits around the country, ranging from club-owned circuits through to the wonderful tracks that the Quinn group has been able to offer us. We race in every condition. Local drivers know how to read weather patterns and some of the weird and wonderful things that we get dished up down here. Kiwi drivers just have a versatility about them.”

There’s also an inbuilt laid-back quality that helps when navigating the inevitable ups and downs of a sporting career. Humility is prized: any sort of prima donna attitude, of the type seen in plenty of highly charged young athletes, is firmly frowned upon.

Lawson impressed on AlphaTauri duties in 2023; he returned to F1 with RB in October to replace the outgoing Daniel Ricciardo

Getty Images

Just look at Liam Lawson. The 22-year-old is one of F1’s hottest properties, having been brought by RB to replace the misfiring Daniel Ricciardo. If he keeps his form, he looks set to be a replacement for Red Bull’s Sergio Pérez. Though he’s been in a high-pressure situation for months, he’s not one for big statements or outspoken shows of frustration. Like most New Zealand drivers Lawson came from relatively humble beginnings, and his father, Jared, took pains to keep him grounded as the young driver’s career ascended the racing ranks.

“There is an underlying ‘us against the world’ determination”

“I remember having conversations with him when he started getting [opportunities] overseas about not taking anything for granted, about remembering where he came from and who helped him,” said Jared Lawson. “I think that coming from New Zealand, which has less than six million people, there is an underlying kind of ‘us against the world’ determination to succeed.”

Then there’s the help. Many in positions of power throughout the local motor sport community grew up watching McLaren, Hulme and Amon. Now, decades later, they’re willing to do what they can to see the country’s best drivers succeed in the way their heroes did.

“There are people – it’s something of an underground community, which I initially wasn’t aware of – who are very passionate about racing who want to see another Kiwi in Formula 1,” said Lawson Sr. “Some of those people, who we’ve been introduced to over the years, now support Liam. It’s quite an amazing thing.”

The right frame of mind

For a nation of five million people, New Zealand is proving itself a reliable source of top-level racing drivers, but as our gallery of competitors shows, the talent tap has been running for decades

Liam Lawson

Bruce McLaren

Getty Images

Mitch Evans

Getty Images

Scott McLaughlin

Greg Murphy

Mike Thackwell

Getty Images

Hayden Paddon

Getty Images

Marcus Armstrong

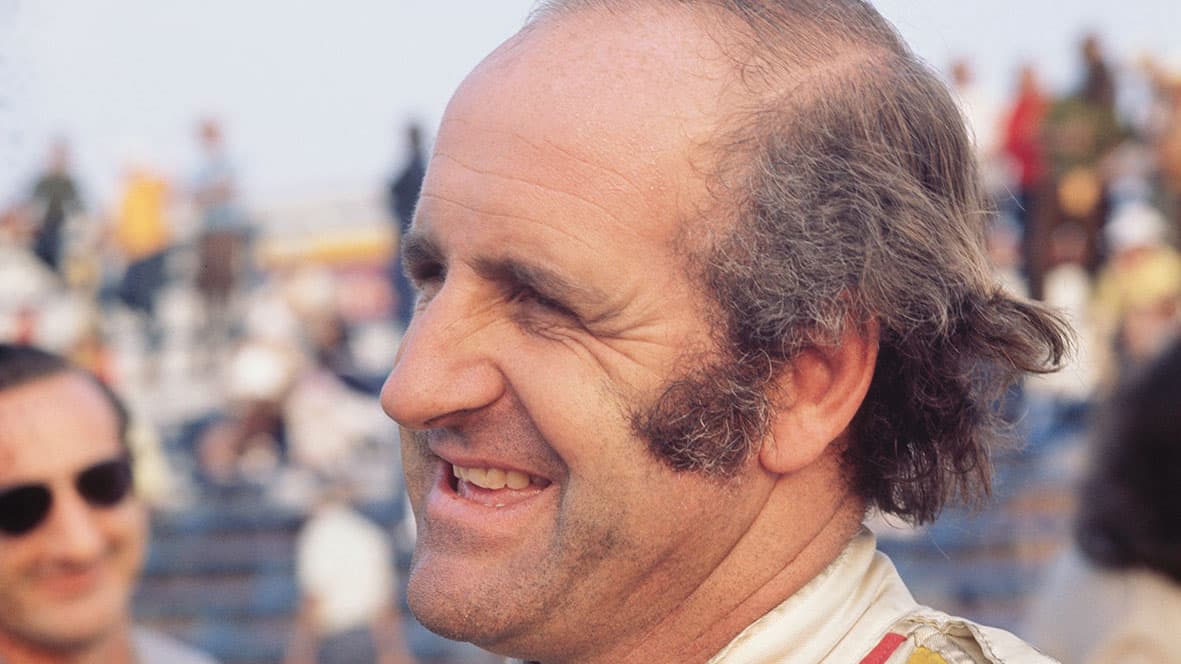

Howden Ganley

Getty Images

Scott Dixon

Nick Cassidy

Brendon Hartley

Shane van Gisbergen

Chris Amon

Getty Images

Earl Bamber

Denny Hulme

Getty Images