Ultimate barn find: McLaren rediscovers forgotten F1 car

McLaren’s M23 powered Emerson Fittipaldi and James Hunt to F1 world titles in 1974 and ’76. Now, the discovery of a forgotten chassis has caused a stir in Woking, as Adam Towler explains

Jonathan Bushell

Two McLaren Formula 1 chassis sit silently side-by-side in a workshop dazzlingly clean, orderly and unremittingly white in decor. Nothing unusual about such a scene at the McLaren Technology Centre, of course: it is the modern face of McLaren Racing; unwavering in its uniformity and regimentation, and this season, blazingly successful, too. While something improbably complicated is being worked on over the corridor in an identical-looking engineering bay, this particular sanctum is McLaren Heritage, and in it, among other racing crown jewels, are two M23s.

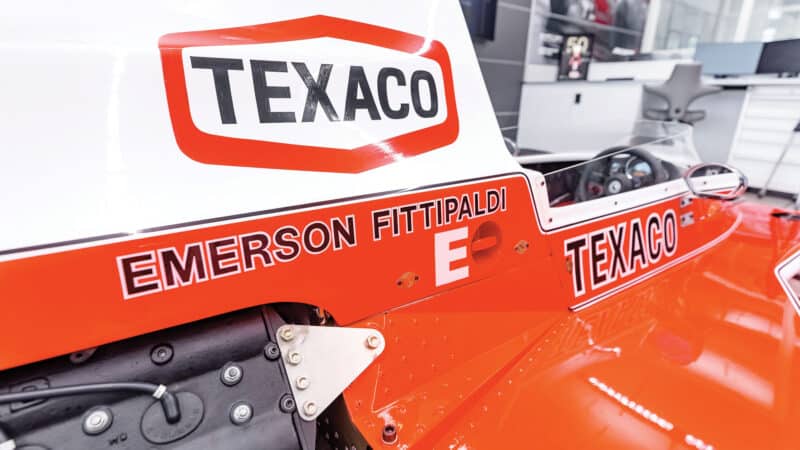

Firstly, the M23 needs no introduction whatsoever. For McLaren it was a car that really shot it to the F1 stratosphere, in 1974 helping the team to its first F1 World Drivers’ Championship with recent Team Lotus defector Emerson Fittipaldi at the wheel, the Brazilian claiming his second title. Or you might be a Peter Revson fan and associate the earlier M23 with the American’s win at the 1973 British Grand Prix in glamorous Yardley livery, rather than Emmo hauling those industrial sideburns to 1974 championship glory in Texaco war paint. Then again, how could we not mention Marlboro and the swashbuckling Hunt, 1976 champions, or Gilles Villeneuve bursting into F1 at the 1977 British Grand Prix? Denny Hulme, Mike Hailwood, Jochen Mass… you get the idea… It’s arguably as much a grand prix classic as anything else that has ever turned a wheel on the grid.

Emerson Fittipaldi, 1974 Swedish GP; a fourth-place on the day kept him at the top of the Formula 1 drivers’ standings

Grand Prix Photo

The premise here is that McLaren has ‘found’ another M23 – ‘chassis 15’ – in its stores, miraculously and slightly eccentrically undiscovered since 1974, and has now rebuilt it to celebrate that championship success exactly 50 years later. And while the reality isn’t quite that of a couple of mechanics with oil-stained overalls pulling a dust sheet off a tub, then we won’t let a little PR embellishment spoil what is still a ripping good yarn with an outcome so beautiful it makes your palms sweat. How could a box-fresh M23 ‘in the metal’ be anything less?

“McLaren has ‘found’ another M23 in its stores, miraculously undiscovered since 1974”

Incidentally, the M23 alongside is chassis 5, Emerson’s winning car from his home grand prix and Belgium that year, but currently more in the spec it ran as a T car in the season finale at Watkins Glen; overall there were – until now – 13 chassis thought to be built, with number 13 omitted for the usual reason. That makes ‘15’ the 14th, if you follow.

Chassis 15 – the 14th M23 (there was no chassis 13).

Jonathan Bushell

The rebuild of 15 is a legacy of Zak Brown coming to power at McLaren Racing. Wanting to make the most of McLaren’s rich heritage, and discovering vast collections of old chassis locked away, his approach has been to use those assets to boost the McLaren brand and inspire new generations of employees and fans alike. To achieve that, Heritage has been brought under the auspices of McLaren Racing COO Piers Thynne, and moved onsite into the same building as the F1 team.

“I’ve been involved in Heritage for a little over two years,” recounts Piers. “One of the big tasks that Neil [Oatley – McLaren’s director of design and development and, of course, designer of so many key McLaren F1 cars in recent decades] did in collaboration was to understand what we had. There were more bits of racing cars and boxes of parts than you can imagine, and we did 90 minutes every week for six months going, ‘Keep, scrap, archive.’ It had to be quite fast-paced because there was so much stuff.” It was during that process that a sheet was pulled back on the M23, and keen to promote the legacy among McLaren’s young engineers, Thynne pressed the go button on a restoration to make the 50th anniversary.

McLaren project manager Julie Coulter has been involved since late ’23

Jonathan Bushell

“The chassis [15] was actually built about 20 years ago,” confirms Oatley. “It wasn’t built in period. It was assembled just as a chassis with the intention of becoming a car some time in the future, and has just sat on the shelf since. The idea was to make it as close as possible to the 1974 Brazilian Grand Prix-winning car, and we’ve largely achieved that. What has surprised me when trying to chase the history of the cars in that period is how much they change race-to-race: it almost makes the current upgrade programme look fairly simple, because almost every race you can see different details. One of those difficulties is that a lot of those pieces on the car aren’t drawn, so we’ve had to work backwards from photographs.”

Chassis 15 is in 1974 Brazilian Grand Prix state; round two, at Interlagos, was Fittipaldi’s first victory in his title-winning year – in chassis 5, right

Jonathan Bushell

Fittipaldi is chomping at the bit to get behind the wheel of 15

Jonathan Bushell

What exactly did McLaren have? No better man to ask than the one who’s brought this legendary machine back to raucous life: “We had the chassis, which hadn’t been finished,” recalls Heritage mechanic Ryan Hogarth. “The impact structure in the side was all missing: it’s just a sheet of glassfibre that runs from front to back, inside the radiator ducts on both sides. We had almost all the front suspension, a gearbox and the majority of the rear suspension, but no engine, no fuel cell, no oil tank, steering rack and no bodywork. So all the rear wing, the rear wing post, that’s all been made. There were no radiators, no pipes or anything [on that side].”

“We wanted to get the young engineering community involved”

According to project manager Julie Coulter, the first step was to lay out what they did have on the floor, and then by using chassis 5, see what fitted, and what didn’t. Coulter worked in bodywork ‘upstairs’ (for the F1 team) and was then brought into Heritage after the project got underway at the end of last year. “We didn’t really have a deadline when we started, “ she recalls, “but we wanted to get the young engineering community involved and had to fit it in around the race calendar, which is another big challenge, because obviously we’ve got so many races now.” The deadline had been set: the 1974 US Grand Prix took place on October 6, 1974. McLaren had a friends and family day at its HQ that same weekend; running the car in front of all the staff seemed an obvious baptism for 15.

The sound of this pristine Cosworth DFV has already been heard in Woking.

Jonathan Bushell

By this point the car was off to The ROFGO Collection, who also have an M23 (chassis 4), and whose airbox was of the correct shape (unlike the item on 5), so the necessary moulds could be taken – an example of the outside support that has also been garnered for this project. Actually making the panels, although in period one of the more straightforward tasks, had its own complications purely because the technology – glassfibre – is now so antiquated as to be a lost and forgotten art in a modern F1 operation. After much deliberation, it was decided to use the recently opened McLaren Racing Composites factory, based at the old McLaren HQ in the Woking Business Park, where three female apprentices, known as ‘The Girls’ by Julie, took to the task. MRC works with prepreg carbon fibre these days so the mucky idiosyncrasies of glassfibre were something new, apart from for one of the more experienced members of the team there, who was able to teach the finer arts of the process to the apprentices.

You wait ages for an M23, then two arrive…

Jonathan Bushell

Work on the car began in July. Ryan did a ‘dry fit’ of all the components over six weeks before sending the car off to paint, fitting the suspension and borrowing another DFV to which the gearbox was attached and the pathway of the linkage assessed.

“Back in the day there was lots of modifying of bits on the car and that was never really captured”

In many ways the entire viability of the project hinged on McLaren having original drawings for the M23, dated from 1973/1974, with which to work from, but as Oatley has already attested to, therein also lied a double-edged sword. With her experience across many aspects of the current F1 car, the contrast with the past has been acute for Coulter, and never more so than when it came to the paperwork. “Never trust a drawing from 1974,” she says with a laugh. “Back in the day there was lots of modifying of bits on the car, and that was never really captured: now everything is all perfectly tracked and you know what state everything is in. They just went with whatever they wanted – ground a bit off here, etc, and that’s what’s caught us out a few times. In theory it should all fit, but in practice… An example was the steering column, which, having been made to spec from the drawings, was found to be 6mm too short. Maybe another drawing was made at the time, maybe one wasn’t, but it certainly doesn’t exist in the McLaren library now. There was nearly a last-minute hiccup with the front suspension too, with certain parts needing to be remade to fit in the build up to the first run of the car at MTC.

Not all parts were a perfect fit at first

Jonathan Bushell

Rapidly, the car began to come together. A new Cosworth DFV was supplied from a well-known UK specialist to correct ‘wide pump’ specification, while Heritage systems engineer Julian Coates unravelled the mysteries of the ‘spark box’ and built up a wiring loom. The wheels are original items, carefully crack tested, and while the evocative rear-view mirrors were bought in, the brackets were water-jet cut out of a flat sheet of aluminium, and then folded into shape by the F1 team’s fabricators. Ryan knows his way around an M23 – he rebuilt chassis 5 earlier in the year – and is confident it would be difficult for the mechanics in period to tell the difference between this car and one of the team’s actual race chassis. Sometimes that attention to detail has made the job harder: the plumbing, for example, has been done with period olive-type connections and fittings instead of the modern swaged fittings used today. Having said that, the central part of the steering wheel has been 3D printed – perhaps the one modern part on the car.

Fittipaldi has been following progress

Jonathan Bushell

When Motor Sport visits, 15 is fresh from having been fired up on the Thursday of the previous week for the first time, and then having been driven along the lakeside in front of the staff on the weekend open day. The plan now is to get the car out for a proper shakedown, once the last small jobs are completed, and for the project volunteers to get trackside and to experience first hand the howl of a Cosworth DFV working in anger.

“One of the other challenges is keeping Emerson Fittipaldi calm”

There is also the ‘Emmo factor’, too. As Ryan confirms, “Emmo remembers everything” about the car, which must be a wonderful sounding board to have during such a restoration. The great man is expected to pay the completed car a visit – his frequent text messages to keep up with progress proof of his enthusiasm for the project. “One of the other challenges is keeping Emerson calm,” says Thynne. “When I first spoke to him about the project, he said, ‘Cool, when can I drive it?’ His rubber stamp on the project was really important and I’ve shared photos with him whenever I’ve seen him at the races. He’s extremely excited about it and has driven the sister chassis regularly. He’s actually met everyone that’s involved in the project, and spoke to all of them. It was quite a powerful moment when we all stood round the chassis in a pile of bits, and he walked into the workshop and shook everyone’s hand; he wanted to understand why they’d volunteered, what their career path was. He spent a lot of time with every individual, which has just underpinned such a positive story.”

15 is now track-ready

Jonathan Bushell

It will surely be an even greater moment when that familiar Café do Brasil-liveried crash helmet finally pokes out from the superstructure of 15 as it chunters out of the pitlane on a deserted British racing circuit for those first, tentative laps. The Emmo M23 magic, 50 years on, accompanied by the music of the Cosworth DFV.

McLaren M23

Engine Cosworth DFV 3-litre V8

Power 465bhp

Transmission Hewland FG400 5-speed manual gearbox

Suspension Front: tubular upper rocker arm, operating inboard coil spring/damper, lower wishbone, antiroll bar; Rear: adjustable top link, reverse lower wishbone, twin radius rods, coil spring/damper, anti-roll car

Chassis Deformable double skinned aluminium monocoque

Weight 575kg