Is Lancia’s LC2 group C monster too wild to tame?

By Donington Park’s very first corner, Andrew Frankel was in trouble, at the wheel of the Porsche-baiting Lancia LC2 — the fastest Group C car of its era

Dean Smith

PHOTOGRAPHY: Dean Smith

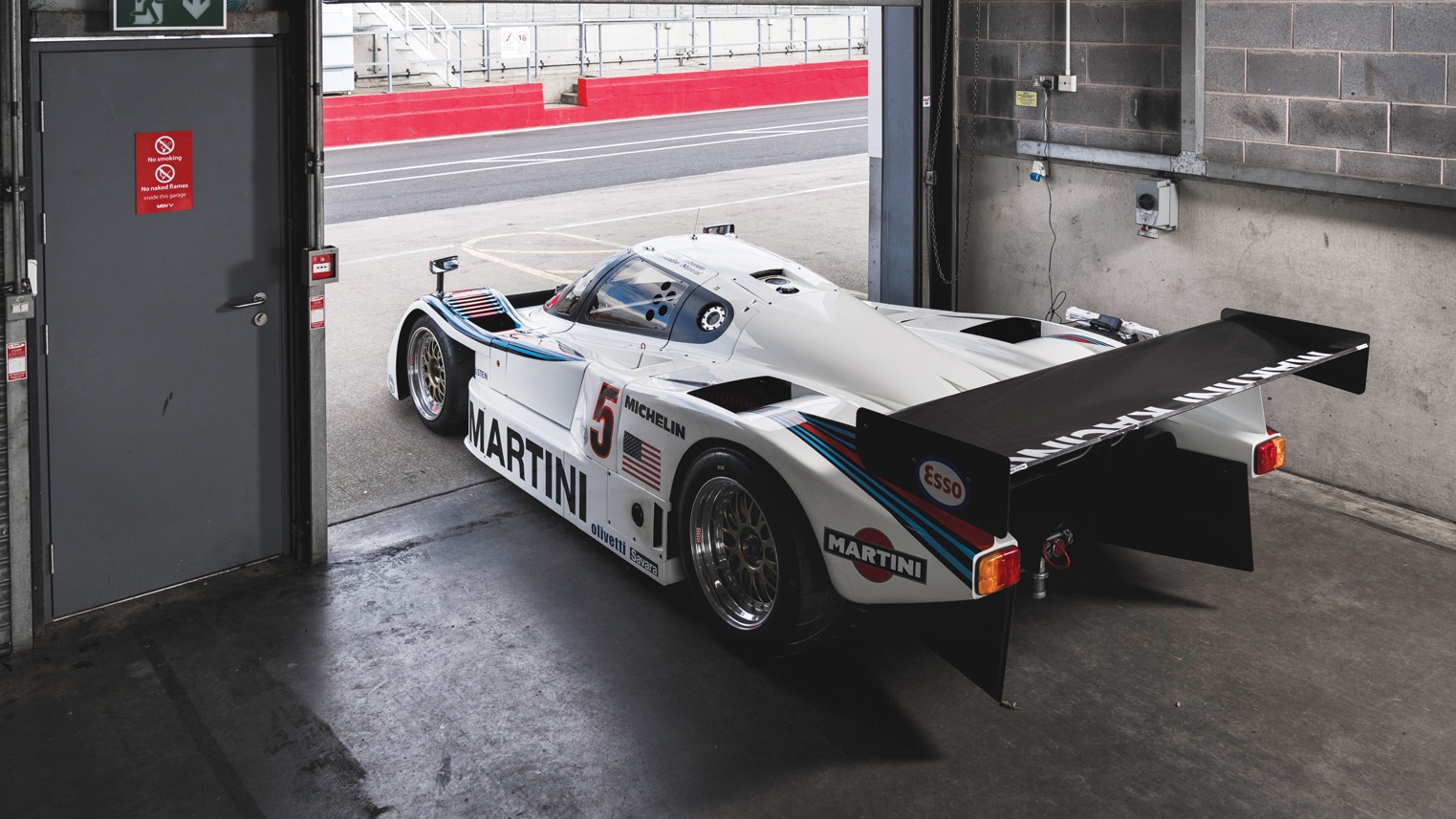

Well this was going to be a first. I’ve been track testing cars for this title for 28 years and can recall just one occasion on which I have left the circuit without intending to, and that was in 1998 when I had a harmless semi-spin in the 1988 Le Mans-winning Jaguar XJR-9LM while exiting the Ford Chicane at that very track. But never have I failed to make it through the first corner before. But now as the Lancia LC2 point blank refused to turn into Redgate approximately 5sec after I’d departed the pitlane for the very first time, I could see no other outcome.

It’s surprising just how rich a seam of insults you can throw at yourself in those few remaining seconds. This wasn’t going to be expensive because I wasn’t going fast enough to hit anything, but it was going to be mightily embarrassing and, on an open Donington test day for unsilenced racing cars, pretty bloody public too. How on earth had I managed to find myself in this situation? Was the truth that I just wasn’t up to driving 800bhp Group C cars any more? How was I to explain this to Max Girardo and his team (where the LC2 is on sale for £2m), all of whom were on the pitwall, eager expressions shortly to be turned into those of pure horror. Unless, unless, unless…

In its three-race career Lancia LC2 chassis 0007 claimed two podiums, two poles and three fastest laps

Dean Smith

Unless the action of the front tyres sliding helplessly across the Donington asphalt generated even the smallest suggestion of surface temperature, but enough – just – to allow them to get a grip of both themselves and the circuit. Which is the only explanation I have for not dumping a couple of million quid’s worth of Lancia in the gravel.

Shocked and relieved in almost equal measure, but now as alert as a bomb squad officer trying to defuse some unexploded ordnance, I tiptoed around the rest of the lap and still managed to almost fall off three more times. In my life to date, I’ve never known understeer like it. I’ve driven a number of cars from this era with pretty uncompromising differentials, but this was a level of unco-operativeness all of its own. Cold, old tyres, thought I. Try harder.

Ferrari V8 engine

Dean Smith

And by swerving around on the straights, left foot braking while accelerating and any other means I could find, I was able to generate enough lateral grip at least no longer to be in danger of making a complete twit of myself. I did another few laps, still being overtaken by pretty much everything out here before returning to the pits and the rueful expressions of the Girardo boys and the good folk from Sporting & Historic who had brought the car to Donington today. I was to be the first person to drive it on a race track since its recent restoration which, for the avoidance of all doubt, was not done by them.

When I tell them what it is like to drive, brows furrow further while I disappear to find a quiet corner and decide if I even want to get back into this truculent, malevolent machine.

It really wasn’t meant to be like this. I have loved the LC2 from afar since the day I first heard that Lancia was going to be the first car company to try seriously to break the stranglehold Porsche had enjoyed in sports car racing during the late 1970s and early 1980s. No disrespect to Stuttgart, I bow to no one in my admiration for what Porsche achieved in its Group 5, Group 6 and Group C campaigns, but all that winning was becoming a bit, well, dull. And the sad truth is that despite the best efforts of the fine group of race car designers, engineers and drivers Lancia charged with taking the fight to Porsche, dull it would remain until a certain Tom Walkinshaw was commissioned by Jaguar to have a go himself. But the Group C Jaguar’s first win would not come until 1986, the last year in which the LC2 ran as a factory entry.

Those three races were at Brands Hatch (1985), Monza and Silverstone (both 1986).

Dean Smith

There were a total of 37 races in the four years that works LC2s raced in the World Sportscar Championship, of which one Porsche or another won an astonishing 32, the five remaining being accounted for by single victories for Sauber, Jaguar and Nissan and two for Lancia. And the first of those was the Kyalami 1000Kms race in 1984 against derisory opposition because, title decided, the big guns didn’t turn up. Whether this was because of a dispute over expenses as claimed or that they simply couldn’t be bothered to make the long trip south is another question. It should also be said that the previous season an LC2 had won the Imola round of the European Endurance Championship, a somewhat opportunistic win in the absence of the factory Porsches.

“The 1985 Spa 1000Kms counts as the LC2’s one and only bona fide victory over the Porsches”

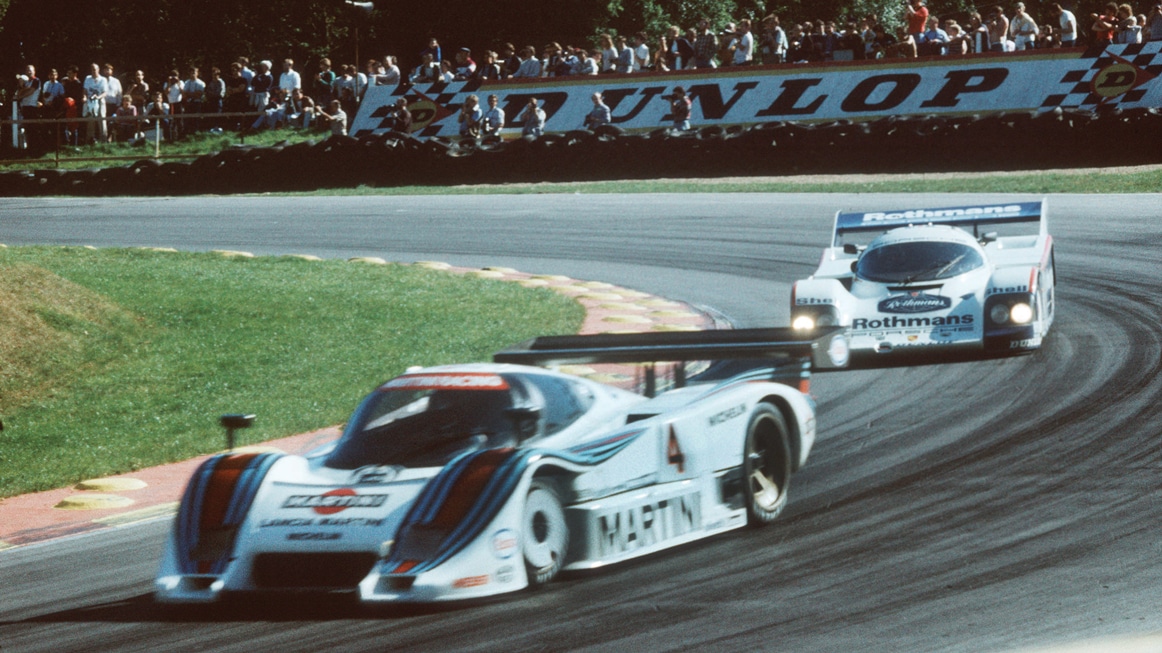

Which left just one race, the 1985 Spa 1000Kms, to count as the one and only bona fide victory over the Porsches, a fact remembered by few today because of the tragic loss of Stefan Bellof in the same event.

Then again, there were just seven LC2s built by the factory, compared to a triple digit number of works and privateer Porsche 956/962s, so its failure – which is how it’s to be seen – has also to be viewed in that context.

A sparse interior but the rev-counter and gauges for oil and water were all that our driver required

Dean Smith

But it wasn’t through any lack of speed. Let’s just run through those races again but this time looking purely at qualifying pace. There were in fact just 23 races in that period that the factory Martini squad turned up for, and LC2s were on pole for over half of them. If you exclude 1983 as a fact-finding mission, an LC2 was the quickest car in qualifying in 11 of the 17 remaining races, taking fastest lap in 10 of them too. No slouch, this.

And this car is chassis 0007, the very last and ultimate specification LC2. It only ever did three races in period but the results speak for themselves: at its first outing at the 1985 Brands Hatch 1000Kms it qualified second – beaten only by another LC2 – scored fastest lap but was relegated to third at the flag by tyre wear issues.

Martini… anytime, any place, anywhere

Dean Smith

With even more power, revised bodywork and now the sole LC2 raced by the factory Squadra Corse team it took pole at Monza in front of an adoring home crowd, almost 2sec faster than the quickest Porsche, and took fastest lap before fuelling trouble set it back to second at the finish

Its last race was at Silverstone where it once more claimed pole, this time with a 1.8sec gap to the works Rothmans Porsche 956 of Hans Stuck, with an average lap speed of almost 150mph, but failed to finish the race thanks to fuel pump failure. But not before it had bagged its third and final fastest lap.

LC2s on front-line service, 1984 Le Mans

Getty Images

So you can see the potential: already in its fifth season of racing the LC2 – this LC2 –was never beaten by a Porsche or any other make in qualifying and never failed to secure fastest lap. Even on the evidence of a front-line career just three races long, one thing is abundantly clear: this LC2 was the fastest Group C car of its era.

“Even on the evidence of a career just three races long, this was the fastest Group C car of its era”

But how did the LC2 become the first car, at least on paper, to outpace the Porsches? Well, no question Lancia was able to recruit a stellar driver line-up – this car alone was raced by Riccardo Patrese, Alessandro Nannini, Andrea de Cesaris, Mauro Baldi and Bob Wollek. There was nothing revolutionary about its Dallara-penned design: it didn’t even have the side-mounted radiators boasted by the Porsches let alone the carbon-fibre construction of the Jaguars that finally ended the Group C Porsche era. But it was a carefully conceived and well-thought-out car. Its tub was crafted around a titanium rollover structure with panels made of a nickel-chromium alloy called Inconel. The engine rested on an aluminium and magnesium alloy called Avional, known for its strength and resistance to cracking, while bodywork was made from a blend of carbon-fibre and Kevlar.

It’s a surprisingly comfortable fit for our lofty track-tester

Dean Smith

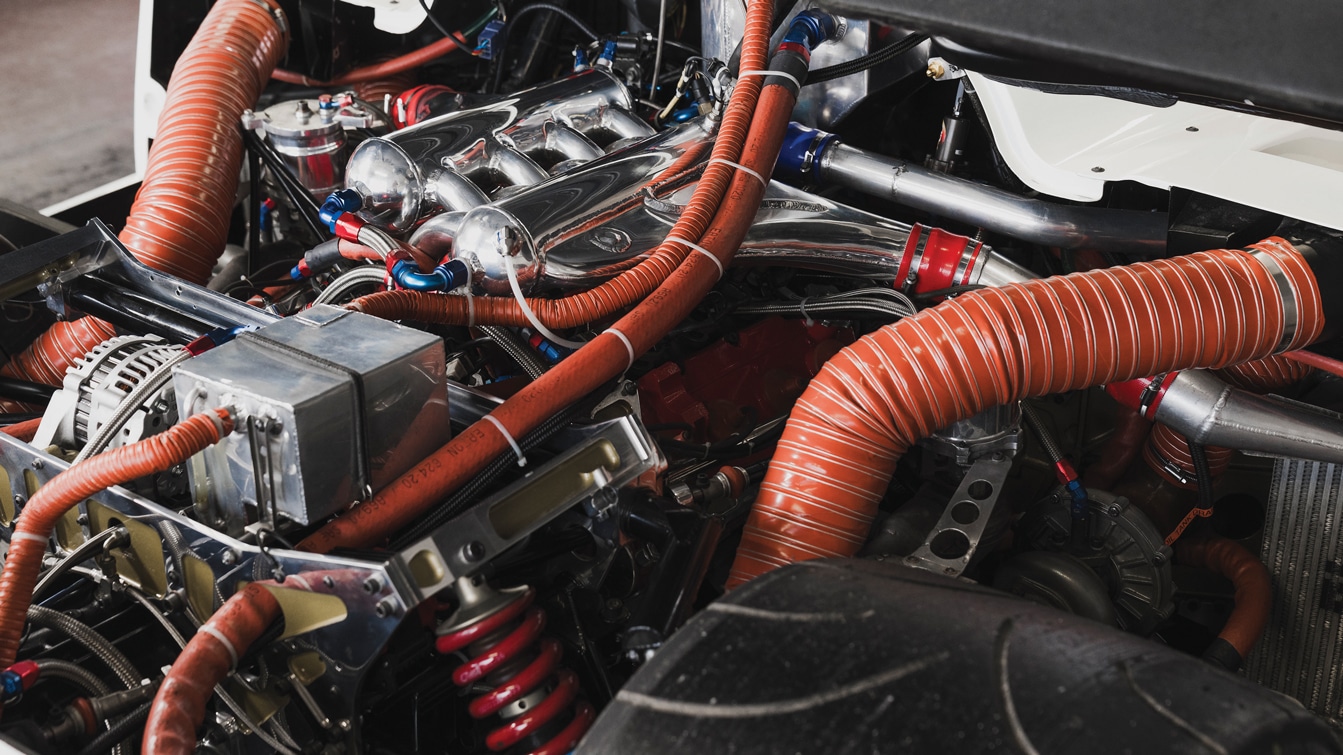

Perhaps, however, it was within that engine that lay the key to phenomenal pace. With both its double championship winning Group 5 Montecarlo Turbo and the Group 6 LC1, Lancia had used its own four-cylinder engine block which Abarth then equipped with a 16-valve head and turbocharger to give some impressive power outputs for its capacity which ranged from 1.4 to 1.7 litres. The LC1, which raced in the Group C era under grandfather rights won three races in 1982, including the Silverstone 6 Hours at which the Porsche 956 made its debut, but for Lancia to compete in Group C proper itself required an all-new car and, with it, an all-new engine it did not have.

Even if it had wanted to, there was no way Lancia would have been able to persuade its existing powerplant to deliver on all three requirements needed for success in Group C: power, reliability and fuel economy. So it turned instead to its Fiat Group stablemates down the road in Maranello which already had an engine that could provide a far better starting point for a brand new Group C motor. This was the 3-litre V8 first seen under the engine cover of the Dino 308 GT4 in 1973. By the time it was ready to race it was essentially new, with dry sump lubrication, four valve heads, twin turbochargers and an initial 2.6-litre capacity to allow the possibility of it racing under IMSA rules in the US, but then expanded to 3 litres for reliability purposes.

Watch out for understeer

Dean Smith

And Ferrari didn’t just get paid for a consultancy job, but used the engine too, first at just under 2.9 litres in the 1984 GTO (more usually known as the 288 GTO) and then slightly over in the F40 in which it would go on to win many races in the mid-1990s BPR era, a decade or more after the engine was designed. The other key difference was that while the racing Lancias used German KKK turbos, the road-going Ferraris relied on Japanese IHI units.

It’s hard to know exactly how much power the engine produced in peak 1986 configuration, though figures of around 850bhp on three bar boost seem believable. Nor do I know what it’s running today though given the boost gauge would register somewhere the far side of two bar at any notice at all, I’d say it was on the healthy side of 700bhp. More than enough to fire me into the Derbyshire countryside, that’s for sure.

I’ve been out of the car for a couple of hours, while the guys from Sporting & Historic try to sort out the problem they’ve inherited. So far as I can work out the diff is essentially locked which is no great surprise, but in combination with a far too stiff set up, minimal track temperature and cold, old slicks, it makes the car almost impossible to drive. This is not the time for half measures and while I’ve been out of the car they’ve managed to soften the front end by fully 40%. I appreciate their efforts and it would be churlish not to have another go. Max GIrardo – a super quick driver – has already been out on the new set-up but is saying nothing: “Andrew, you must draw your own conclusions…”

More in hope than expectation I clamber over the wide sill and lower myself into the LC2. A few things to note, the first of which is that it’s so spacious even 6ft 3in me is comfortable, more so by a distance than in any other Group C car. I have legroom, headroom, shoulder room too; I wonder what effect such a huge cockpit bubble has on the flow of air to the rear wing. I’m not complaining. I guess they did it to speed driver ingress and egress at pitstops.

“By the mid-80s the LC2 had the talent to be the Porsche-humbler”

The driving position is offset and the dashboard layout has had minimal thought applied, but really all I need to see are the oil and water gauges, the rev-counter and boost dial. The engine booms into life, full of raw, mechanical thrashings and no little menace. But the traditional five-speed Hewland box with its dogleg first clunks satisfyingly into gear and with a reasonably gentle clutch it’s not difficult to pull away without stalling it.

Redgate approaches and, let the heavens be praised, the Lancia turns. Gingerly I pad my way around the first lap because I still don’t trust it, but it goes where I point it. Miracles have been worked and it seems I am going to be able to drive this car after all. Time to find out more. Out of the tight left that leads onto the pitstraight, short shift from second to third because I expect I’ve still not got enough tyre temperature for the rear boots to wear full throttle, then give it everything.

Catch me if you can: LC2 vs Rothmans Porsche, Brands Hatch, 1985

Alamy

The amazing thing is you don’t have to wait. With just 3000rpm on the clock the boost gauge needle flicks, the intake growl hardens and at once you’re flying and in urgent need of another gear. Forward and across into fourth – this might be the sweetest Hewland I’ve tried – then back into fifth with essentially unabated acceleration. It’s ability to gather speed is spellbinding and courtesy of not just Enzo’s engineers but clearly the sprintiest of sprint gear sets. On the main straight I sit parked at max permissible revs for what seems about an hour.

Yet slowly it’s all coming together and it’s that engine that’s making it all happen. For its outrageous power the throttle response is so good, the turbo lag so manageable you can use it to play with your lines, which is as well because for all that has been achieved with the set-up, it’s still a car that wants to understeer. But now you can lift and tuck the nose in, then let the power push you towards the exit before unleashing it all on the straight beyond. All that torque over such a wide rev range combined with such short gearing means you can be a gear or even two higher than you might expect in any given corner and still it’ll swat you down the straight beyond as if it were barely there.

Perhaps a little more fettling was required on this £2m monster but it’s going to give much joy to its next owner…

This was a different car to that which I’d driven earlier, having experienced the single biggest improvement from one set-up change I’ve known; but you can tell it could be better. A single day testing with someone who really knows this kind of car could turn it into something even more rewarding.

Because the LC2 never lacked pace, as anyone watching qualifying for Le Mans in 1984 – where its pole time was 9sec quicker than that of any other make of car – will attest. What it lacked was reliability: even those races where one or more was still there at the flag, the kind of trouble-free runs expected by Porsche factory and private teams were usually no more than a distant dream. The pity is that by the mid-1980s the LC2 had the talent to be the Porsche-humbler so many were waiting for. The talent, but not the stamina: it was that which proved decisive.

Lancia LC2

Engine Ferrari 308C 3 litres, V8, twin turbocharged

Chassis Aluminium monocoque

Power 800bhp

Transmission Hewland 5-speed manual

Suspension (front & rear) Double wishbones, coil springs over damper

Weight 850kg

With special thanks to Girardo & Co, Sporting & Historic and Donington Park.