Praga Bohema track test: the ultimate road-legal hypercar?

Praga has seen its stock rise in the racing paddock and now it’s tackling the road-legal hypercar market. Stephen Dobie tests the boundaries of the Bohema

Marc Bow

The fastest street car at the race track.” That’s the goal for the Praga Bohema, the latest entrant into an oddly bustling marketplace: the £1m-plus plaything. But this one is designed to really stand out in an owner’s collection, and not just because of its truly arresting, aerodynamically led design.

It’s not the first production car in the Czech company’s storied 115-year history, with the road-legal Praga R1R of recent years described as a ‘proof of concept’ for the Bohema, even if nothing is carried over.

While Praga made its first car in 1909, it’s only started building its motor sport reputation in the last three decades, dipping into enduro, karting, Formula 4 and more recently Britcar here in the UK. While not a big-league name just yet, its work in getting there has thus far been canny. Recruiting sim racer Jimmy Broadbent as a driver alongside Gordie Mutch – the pair won the inaugural Praga Cup – looks a stroke of genius. Wooing Broadbent’s 843,000 YouTube subscribers is surely the 2020s evolution of embedding yourself in the hearts of Gran Turismo gamers, for whom the Nissan GT-R became the ultimate poster car.

The tech-fiilled steering wheel has been designed in-house by Praga and has been three years in the making

Marc Bow

Marc Bow

Marc Bow

Which brings us neatly to the fundamentals powering the Bohema. There’s no highly tuned four-cylinder as found in the R1, rather the 3.8-litre twin-turbo V6 of that iconic Nissan. Here it sits in the middle of the car and drives the rear wheels only, and if Praga hits its 982kg target for the final production car – we’re getting our mitts on a slightly heavier prototype here – it’ll be propelling a little over half the weight it’s used to. Praga hasn’t simply ordered enough V6s to fill the Bohema’s 89-car run and slotted them into place, though; serious work has gone into making this engine more fit for purpose.

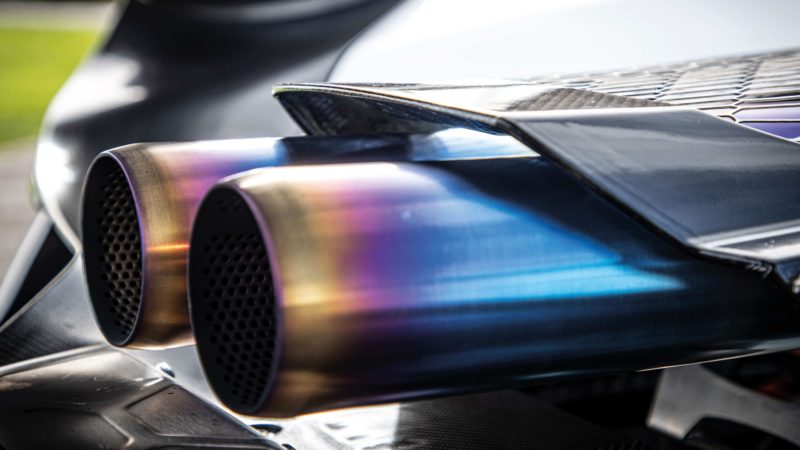

The company has designed its own dry sump conversion to take a vital 14cm out of its height while there are new turbos from famed British GT-R tuner Iain Litchfield. “We’ve done the sump design and Iain will do the production,” says chief engineer Jan Martinek. “We buy engines from Nissan and they go directly to Litchfield – we all work very well together! We also spoke to other manufacturers and had approval from Audi for its V10. It would have been interesting – and made a nicer sound – but we would have been stuck with 600bhp. Audi said yes but it wasn’t a co-operation, just an engine. Nissan wanted it to be a partnership.”

This V6 also allows room for the model to evolve, especially with Litchfield involved. Figures are yet to be finalised, but the targets are 700bhp and 535lb ft, enough for a 0-62mph time below 3.5sec and 0-124mph in under eight. The top speed is 190mph, limited not by the car, but by Praga’s targets. “You don’t need any more on track,” we’re assured. Of more importance was another stat: 900kg. That’s the minimum downforce the Bohema will produce at 155mph, necessitating a design more akin to an actual race car than the road car the Bohema is claimed to be.

Marc Bow

Finished Bohemas should be here by the second half of 2023

Marc Bow

Praga didn’t want to scare customers off with aggressive looks – but may have failed here…

Marc Bow

“Squeezing in all the necessary components had its problems,” adds Martinek. “Every square centimetre behind the panels is used for the systems. Power steering, ABS, an electric clutch, air-con, a reservoir for windscreen washer fluid, motors for the wipers. The packaging was the biggest challenge of the car.”

While air con and a place to slot your phone are included, this is no conventional supercar interior. Not least because the door’s aperture sits high and requires an assertive yet balletic entry procedure: bum on the sill, one hand on the roof, then swing your feet over and onto the seat before nestling down, legs straight into the (adjustable) pedal box. The seat doesn’t slide fore or aft but pivots up and down in a way that keeps your posterior low but places your eyes where they need to be. Each detail has so clearly been agonised over.

“The Aston Martin Valkyrie is the best thing that could have happened to us,” Martinek laughs, “as it has a similar entry procedure. Suddenly it’s cool. Having heard lots of negative comments before – ‘I have a bad back, this isn’t for me’ – it’s no longer an issue.”

Perhaps most bewitching of all is the steering wheel, developed in-house and three years in the making. Everyone in the factory tried it with and without gloves to perfect its grip levels for a breadth of drivers. I won’t have time to adjust too much today, but by production you’ll be able to alter steering wheel weight and traction control levels via its buttons and screen, which also acts as the instrument gauge. Now I’m ensconced in the car and have my hands wrapped around it, it’d be rude not to slip gently out onto Dunsfold Aerodrome for a taster of Praga’s work so far…

Not without a briefing from chief test driver Josef Král, though. He’s worked with Praga for six years – covering the length of the project – and has single-seaters and GT3 cars on his rich motor sport CV. He’s also huge fun to be around, only increasing my desire to keep his pet project looking exactly as it did rolling off the transporter this morning.

“The top speed is 190mph, limited not by the car, but by Praga’s targets”

“I’d say 700bhp is a lot for a car when it weighs under a tonne,” he smiles, before telling me Romain Grosjean spun it while attempting to drift. Perhaps it’s helpful this prototype is running closer to 550bhp, but I’ve a feeling it’s not going to be overly hamstrung.

We begin with a potter around Dunsfold’s notoriously rutted access roads – which hobbled the stock BMW 2 Series I drove in this morning – to show that while the Bohema won’t be troubling Rolls-Royces, it’s more habitable than its elbow-Tetris interior might have you believe. Král and his team have been putting development miles on roads as well as the racetrack, just to prove the road-legal status isn’t a wonderfully mad box-ticking exercise. So while the side mirrors are visibly wobbling on their beautiful, aerodynamically functional struts, the sensation isn’t mirrored through our seats.

It’s absurd to hear the familiar GT-R soundtrack in something so specialist, but the newly dramatic punctuation of its sharper sequential shifts (with helical cut gears to avoid any whine) lends the aural experience some welcome new character. With a quick warning that the traction control is set at its lowest – “so be careful with the power!” – we peel onto the track.

Luggage space is courtesy of exterior side pods in a move reminiscent of the McLaren F1

Marc Bow

True to Král’s word, there’s blatantly little in the way of a safety net on the early morning autumnal asphalt, but there’s an impressive approachability to the way those new turbos spool. Power can be fed on with prudent vigour. There’s little in the way of corrective lock needed, even as my confidence rises and I apply the throttle earlier out of corners. There’s a sensation of the rear wheels oh-so-slightly overdriving with no fear attached to it – nor any loss of forward momentum. Outright aggression with the controls might weave a different tale but this is a car that’s easy and exciting to build pace in. Crucially, it leaves you wanting more without scaring you. While I’m far from diving into the deep end of its downforce, the seed has been sown. I want to spend all day learning this thing.

“There’s an impressive approachability to the way those new turbos spool”

Luckily my mentor knows it well and is happy to demonstrate what I couldn’t by swapping seats. The G-force as Král negotiates follow-through boggles my mind, not least because we’re in a car wearing road-legal Pirelli P Zero Trofeo Rs. “On slicks this is more fun than a GT3 category car,” he grins. “There are no limitations – we’re in a different rulebook. It can be fun to slide a car around like a Caterham but it’s a different feeling to use downforce and experience real G-force. When you drive it for the first time, it’s tough to understand, but we’ve made the aero pick-up point as low and progressive as possible. So it’s not a case of ‘nothing, nothing, nothing’ then suddenly so much grip. A smooth transition is one of the main goals I wanted to reach.”

Praga will continue campaigning the R1 racing car, with the Praga Cup set to integrate into the Britcar set-up for its five-round Prototype Cup in 2023, the Bohema living an adjacent life as a road car for now. Král and his team haven’t recorded a lap time around Dunsfold yet, but it’s safe to assume it’ll stand a strong chance of a record. There’ll be no official Nürburgring visit, but Praga expects some customers might head there.

While the target may have been speed, it feels like the Bohema has achieved something far less prosaic: being a purely petrol-powered hypercar that will offer its owners an addictive learning curve compared to the other rarities it shares garage space with. More than any other car they own, I think I might be envious of this one.

Target Spec

Price: Approx £1.3m

Engine: 3.8-litre V6

Power: 700bhp

Torque: 535lb ft

Weight: 982kg

0-62mph: 3.5sec

Max Speed: 190mph