Delage à trois: 1927 British GP winners reunited

The 1927 British GP, held at Brooklands, witnessed a historic 1-2-3 for French maker Delage. Ninety-five years later, Damien Smith is present for a special celebration where a trio of 15-S-8s, two from the race, return to the banking

Russell Sach

The three cars poised on the rough concrete banking look right at home – largely because that’s precisely where they are. Strictly speaking, they’re French-minted racing royalty, but nevertheless Brooklands is spiritually fitting, even if it’s been an awful long time since Delage grand prix cars of this particularly fine vintage have been seen in such number on the ancient Surrey speedbowl. No wonder museum vice-president Allan Winn is quietly beaming, given his work to make this reunion a reality. One of the owners, the spit of Terry Gilliam in incongruous long woollen coat, his spiked grey hair set off by the rings of studs pierced through his ears, is also smiling. “I feel a sense of history,” he says with grandeur. We all do.

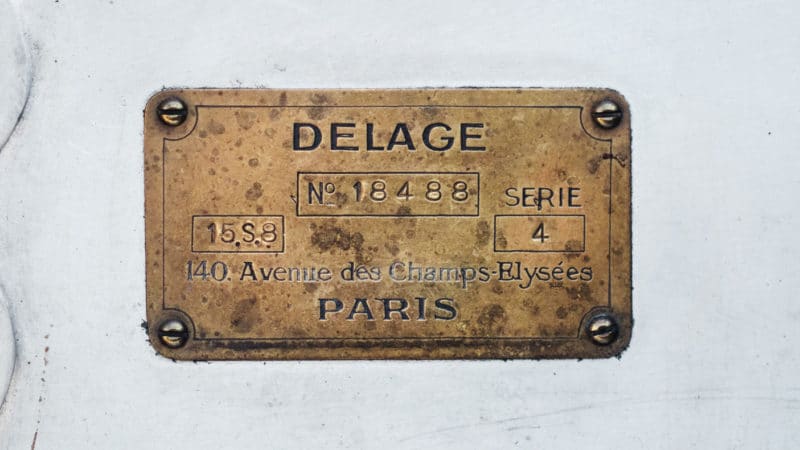

On September 4, 1927, two of these three Delage 15-S-8s were lined up on the Railway Straight to take the start of the second-ever grand prix in Britian. The petrol-blue one, chassis No2, survived rain and high winds to finish as runner-up in the hands of Edmond Bourlier, behind winner and future war hero Robert Benoist in chassis No3, with the black car, chassis No4 driven by Albert Divo, completing yet another Delage 1-2-3 clean sweep. The performance left Benoist unbeaten across the 1927 grand prix season, repeating Delage’s Brooklands victory of the previous year, to crown the French company as what turned out to be the last Manufacturers’ World Champion (for now).

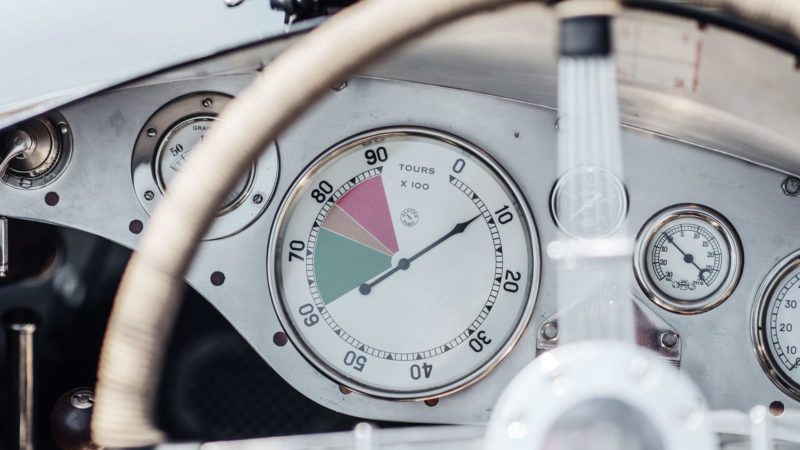

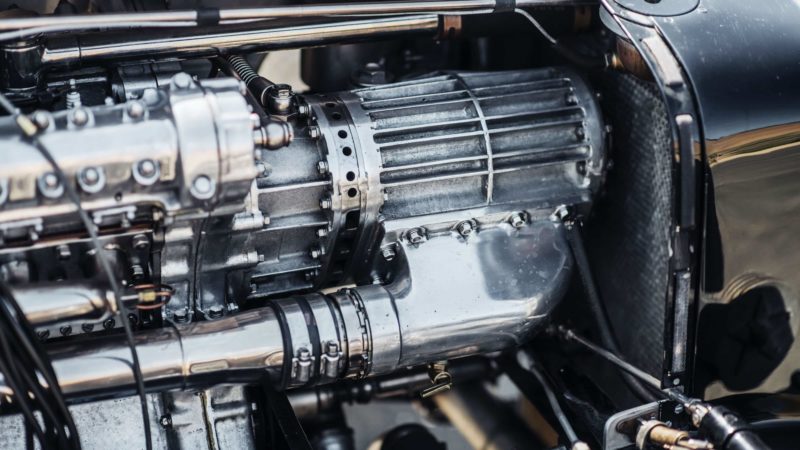

1.5-litre straight eight

Courtney Frisk ©2021 Courtesy of RM Auctions

Produit de France

Courtney Frisk ©2021 Courtesy of RM Auctions

The 15-S-8 dominated grand prix racing in 1927

Courtney Frisk ©2021 Courtesy of RM Auctions

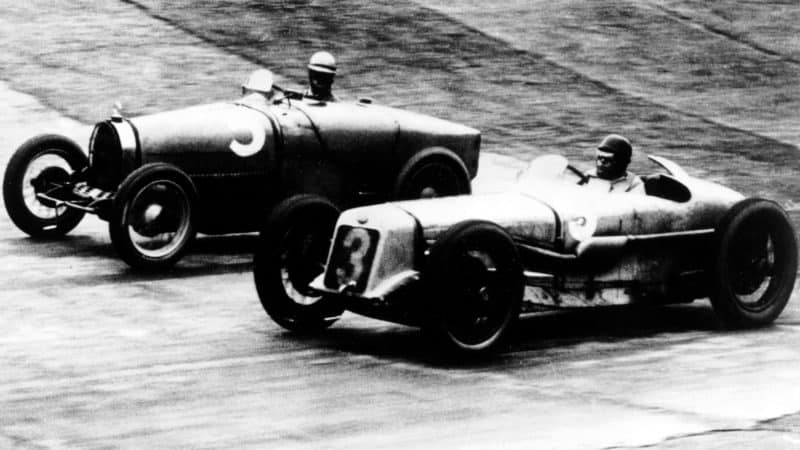

Edmond Bourlier’s Delage (No3) is neck and neck in the 1927 RAC GP with the Bugatti of Malcolm Campbell.

Getty Images

In an era when Bugatti held sway, this year was a stark and sobering exception as Delage’s 1½-litre blown straight eights blared across Europe in a glorious cacophony, before the company departed never to return in a swirl of financial wrack and ruin.

Not that it was the end of the story for the cars themselves, of course. Take chassis No4. Almost 10 years after Divo’s Brooklands podium, the car found its way to a promising Brit with high ambition. Richard Seaman’s race-winning, ERA-defeating exploits through 1936, in a supposedly outdated but still potent grand prix car now classed as a voiturette, caught the eye of Alfred Neubauer and led him directly into a prized seat at Mercedes-Benz. The ageing Delage was a powerful means to a glorious but ultimately tragic end, given Seaman’s fate at Spa in 1939.

“Delage’s 1½-litre blown straight eights blared across Europe”

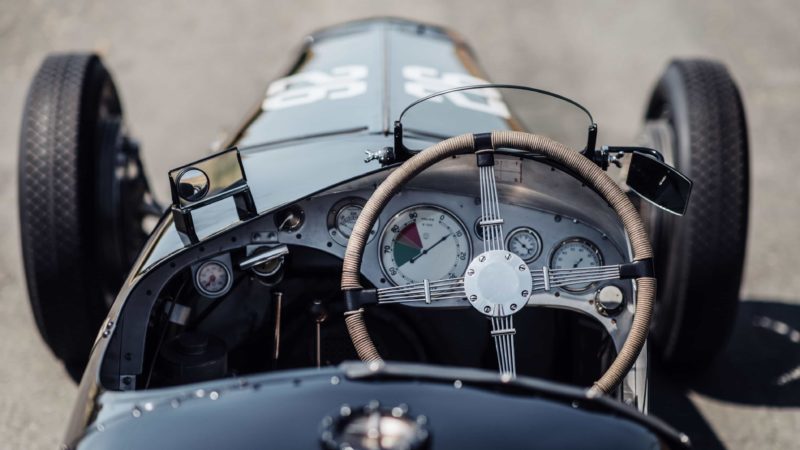

Low slung and perfectly proportioned, the 15-S-8 looks sleeker and meaner than a Bugatti. To our eyes it’s ahead of its time, so Lord knows how it must have appeared to its stunned contemporaries. The model was conceived to meet the new grand prix regulations set for 1926, mandating a minimum weight of 600kg and a reduced maximum capacity of just 1500cc, either supercharged or unsupercharged – shades of a distant future, 1961. Albert Lory designed the 15-S-8 on a broadly similar chassis, braking system and transmission to Delage’s previous 2 LCV, powered by a game-changer of a blown straight eight. Featuring a nickel-chromium crankshaft, the engine included no less than a total of 36 roller bearings and 26 ball bearings (according to Daniel Cabart and Christophe Pund’s definitive 2017 book Delage: Champion du Monde), gear-driven twin-cam valve operation and a two-stage Roots-type supercharger, for an output of some 170hp at 8000rpm. New and enthralling territory.

On the incline 95 years after the French 1-2-3 at Brooklands.

Russell Sach

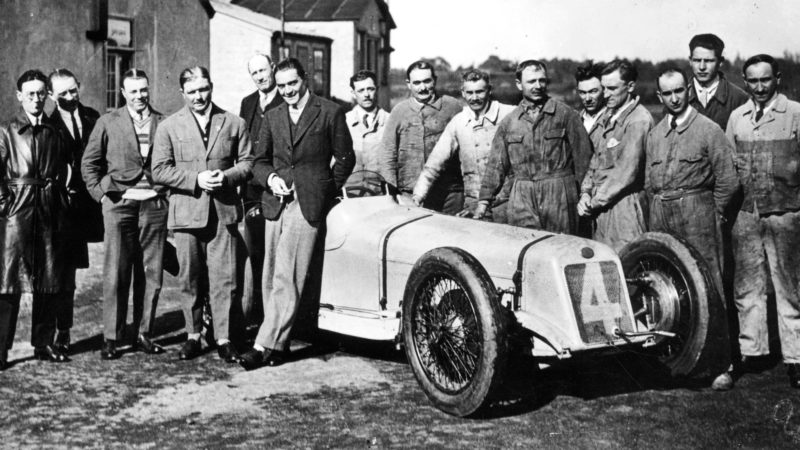

Robert Benoist practising before the 1926 RAC GP – the first such event in Britain

Getty Images

While the car stamped its mark in 1926 at Brooklands, the poor drivers suffered for their art. The following year, four works examples were prepared for the grand prix season with key modifications including a relocation of the exhausts to save the pilots from severe burns, while the engine was shifted 4in to the left to lower their seating position. Benoist won all four grands prix, with the quartet of chassis all contributing to the world title. Along with Divo’s third at the British GP, André Morel completed an earlier podium sweep in chassis No4 at Montlhéry. At Brooklands, the three Delages on the entry faced a thin field of six Bugattis and two Thomas Specials that had little hope of keeping the British end up. Consequently and absolutely to form, the 15-S-8s put on a procession over 125 laps that doesn’t exactly sound like a thriller. Benoist ran third for much of the way behind Bourlier and Divo, before what appears like team orders allowed him to complete his set of grand prix victories, Divo pitting twice late on for a loose exhaust and ‘seat adjustments’.

Thereafter, Delage’s grand prix team was disbanded, although exactly how much the racing efforts had contributed to the financial woe is open to question. “The French do this from time to time,” says our Terry Gilliam look-a-like, collector and new owner of No4 (for the second time), Abba Kogan. “They come in, do their thing and then they depart. They did the same thing with Matras, the only team outside of Ferrari to win in F1 as well as sports prototypes in the same year. They dominated sports prototypes for three years, 1972 to 1974, then they quit. Renault did the same thing and then quit. I kind of like that about the French. Enough: let’s show them what we can do. That’s what inspired me to be an owner of one of these very few cars.”

Earl Howe on his way to victory in his Delage at the BARC Whitsun Meeting, 1931.

Getty Images

Inevitably, the four 1927 works Delages have labyrinthine and at times tumultuous histories, but all have somehow survived. Chassis No1 sits in the Collier Collection at the fabled Revs Institute in Florida; No2 is the Brooklands car, kindly bequeathed to the museum in 2012 in the will of Alan Burnard, but for now a non-runner as the engine is currently “in pieces”, according to Winn; No3 is being restored in France; and No4 is back in the hands of Kogan, looking pristine under the care of Hall & Hall.

What a story this car has. Once Delage had pulled the grand prix plug, Louis Chiron – best of the Bugatti rest that day at Brooklands – bought the car and used it to finish a fine seventh at the 1929 Indianapolis 500, on the lead lap as the first non-American car home. Delage mainstay Robert Sénéchal then picked it up and returned No4 to European racing – sixth at the French GP in 1930, fifth in ’31 – before selling it on to Earl Howe, who had also become the custodian of No3 which he crashed at Monza. Now classed a voiturette, No4 logged more results of significance during the early 1930s, including a win at the 1933 Eifelrennen, before Howe switched to an ERA for 1936 and passed the Delage on to Seaman. The Englishman retained celebrated Alfa Romeo riding mechanic and test driver Giulio Ramponi, who gave the car another lease of life through extensive weight-saving revisions and a conversion to hydraulic brakes.

Defying his own initial doubts over the Delage’s creaking vintage, Seaman won the 200-mile RAC Light-Car Race on the Isle of Man, the Coppa Acerbo at Pescara, the Prix de Berne and the JCC 200 Mile Race at Donington Park. Neubauer approved.

Benoist (leaning on car) became a Resistance hero after his racing exploits

Getty Images

No5 with Paul-Emile Bessade at the wheel

Russell Sach

Jaeger of Paris dial

No5 with Paul-Emile Bessade at the wheel

The portly Mercedes team manager was not the only one watching. Prince Chula Chakrabongse of Siam had been impressed by the Delage and Seaman’s defeats of his cousin ‘B Bira’, and then some. Not only did he buy both No4 and No2, he commissioned Lory to design a new pair of 15-S-8s with independent front suspension. The 1927 old stagers became parts donors to the newly created No5 and No6 built by Rubery Owen. Chassis No5, known then as WMG 101, was constructed from the best components taken from No4 and with the engine from No2. Today it joins us at Brooklands, looking resplendent under the ownership of Paul-Emile Bessade.

“The four 1927 works Delages have tumultuous histories”

Once war broke out, Chula sold all his Delage stock to Reg Parnell, who is thought to have owned all the cars except No1. This is where histories became tangled as parts and even engines were chopped and changed between chassis. Post-hostilities, Parnell resurrected No5 using bodywork from No4, and subsequently it was campaigned by Barry Woodall in hastily repainted British Racing Green thanks to a fussy scrutineer’s demands for the driver’s national colours. Woodall raced it in the 1947 British Empire Trophy and at the Ulster Trophy finished a fine second to Bob Gerard in ERA R14B. But when it threw a rod a year later at the Jersey road races, he sold it on to friend and Aston Martin enthusiast Jack Rowley. The subsequent succession of owners included Anthony Bamford in the 1970s, when Willie Green raced it with aplomb on the burgeoning historic scene.

Black is the colour Richard Seaman chose for his racing cars, including the Delage that he and Ramponi rejuvenated

Russell Sach

As for chassis No4, from Parnell it fell to David Hampshire, and then on to a certain RRC Walker, aspiring team patron, and invigorated by Tony Rolt to embark on the single-seater scene. Walker’s first choice was the 1½-litre Mercedes W165 of 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix fame, but what would have been a fascinating line of history was cut short by military red tape scuppering a sale brokered by Rudi Caracciola, no less. A 4½-litre Grand Prix Lago-Talbot was the next target, but exchange control regulations demanded the only foreign cars to be sold in Britain should be for display at the Earl’s Court Motor Show – and the Lago-Talbot was a racing car, not for the road, so was deemed ineligible. Thus Walker, with prompting from Parnell, turned to Delages – in the plural. He bought two: chassis No6 from Dick Habershon, which was in “perfect” working order, and No4, which fell a long way short of that. In fact Walker was horrified by its condition, saying it had to be “stripped immediately before it fell to pieces!”

His intention had been to cannibalise No4 for spares, as Chula had done – before investigations revealed its history as ‘the Seaman car’. Delighted, Walker embarked on its complete restoration to 1936-spec glory. Meanwhile, No6 was used and regularly, fitted with an ERA engine from 1951 after persistent Delage failures, Walker running with double rear tyres at the Brighton Speed Trials. As for the restoration of No4, it wasn’t until the mid-1960s, long after the Walker team’s Stirling Moss-inspired heyday, that loyal mechanic John Chisman had the Delage close to completion. The finishing touch was a badge for the grille, fashioned by a local gunsmith whose French wife just happened to be an ex-Delage employee and could describe its design in detail. Then, disaster.

Abba Kogan

Russell Sach

Game-changing engine

Courtney Frisk ©2021 Courtesy of RM Auctions

Pristine condition thanks to Hall & Hall

Courtney Frisk ©2021 Courtesy of RM Auctions

Another Delage win – Seaman, Isle of Man, 1931

Getty Images

The inferno that ripped through Walker’s Dorking premises in 1968 robbed the patron (and us) of so much: the stripped Lotus 49 Jo Siffert had recently crashed in the Brands Hatch Race of Champions, two new Cosworth DFVs, Cooper-Maserati, Type 52 Bugatti, more than 30 years of souvenirs, photos and pre-war press clippings, and even one of Stirling’s worn tyres from the landmark 1958 Argentine GP. The cherished Delage was a charred casualty too, staff initially hiding the burned-out wreck from the boss to spare further anguish.

It was an insurance write-off, the blaze having melted the sagging steel girder-frame chassis and almost everything else inside and on the car. Except when Chisman tried the starting handle, miraculously the straight eight still turned over. Could they pull a phoenix act? It remains one of the most remarkable automotive resurrections. Under the artisan eye of Chisman, the car was painstakingly rebuilt from newly made parts and others sourced from a long list of sympathetic suppliers, most of whom considered much-admired Walker a friend. There are some lovely stories. At the 1968 German GP, Rob carried what used to be the magneto to show Bosch’s competitions manager Fritz Jüttner. Upon inspection back at base it was judged unsalvageable, only for Jüttner to telegram Walker to inform him the company had found one similar in its museum. “Please accept it compliments of Bosch.”

Then there were the two baulks of timber Ramponi had installed back in 1936 to strengthen the chassis and reduce flexing, key to realising the car’s true identity following the sale to Walker. Now his local undertaker, Sherlocks, replaced them with finest coffin oak.

Howe with one of his Delages at Brooklands, 1931.

Getty Images

Remarkably, the reborn Delage returned to public view at the 1970 Jacky Ickx Racing Car Show in Brussels. When it fired up, the cacophony cleared the hall. Exhibited for years in Tom Wheatcroft’s Donington Collection, the 15-S-8 stands among pre-war Mercedes and Auto Unions, BRM’s V16 and Matra’s V12 as one of racing’s most aurally dramatic creations. Following a final public flourish on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice, Walker sold his beloved Delage in 1984 to French collector and publisher Serge Pozzoli for £130,000.

Ten years later, following Pozzoli’s death, Abba Kogan bought the car and commissioned a fresh 1936-spec overhaul by Auto Restorations in New Zealand. The car passed to Peter Giddings without Kogan having ever driven it. Now, following Giddings’ death, Kogan has it back, bought at RM Sotheby’s Monterey sale last year for a bargain £750,000 – much less than he’d sold it for. Today back at Brooklands, Kogan is ready to drive it for the first time.

Rob Hall has warmed it over on the Finishing Straight, then insists the owner takes the wheel for our photos on the Members’ Banking. The rutted surface limits Kogan to a gentle trundle, but neck hairs rise as No4 returns to a scene from 95 years ago. Then we transfer to Mercedes-Benz World next door, where time awaits for a proper run on the smooth, modern test track. The looks on faces as Kogan passes through the gates and past bemused Mercedes owners are predictable – although pleasingly few cover their ears.

“When the Delage fired up, the cacophony cleared the hall”

Motor Sport lends Rob a hand for a push-start, but having run perfectly all morning suddenly No4 won’t fire. No fuel pressure. Brow furrowed, Rob checks the tank – it’s near empty. He’d poured in 45 litres first thing, but the warm-up, short banking run and trundle to Mercedes had drained most of it. Never mind. A quick refill and we’re ready to go again. This time the black beauty fires and Kogan, helmeted but dressed more like vintage-era Keith Richards than vintage racer, tentatively lets the eight sing. He’s careful, understandably, but warms to the task as Mercedes kindly adds minutes to our track time. He’ll have about 15. “If he has enough fuel,” murmurs Rob with a smile. He does.

Kogan has owned this 15-S-8 twice – but here at Brooklands was the first time he’d ever driven the car

Russell Sach

“These Delages are monumental,” says Kogan. “How they swept the opposition in 1927, then suddenly left, as if to prove a point. That kind of superiority is rarely witnessed, particularly when a car from this stock 10 years later eats up good drivers in the voiturette class, and kept up this amazing heritage.”

Why did he buy it back? “I felt it was a must to own it again. And I missed it, plus I had never driven it. The opportunity arose for me to buy it again, and I did, happily. Cars gave us freedom from the horse and buggy. So I think they are a good thing! In my collection we try to come up with a few gems. I’m always looking for a cutting edge, a pure blood.” In the wheel-tracks of Divo, Chiron, Howe, Seaman and Walker, he’s found one.