Farewell to Valentino Rossi, the man who transformed motorbike racing

After 26 seasons in the saddle and nine world championships, Valentino Rossi’s career on two wheels has finally reached the finish line. Mat Oxley pays tribute to the MotoGP maestro

Studio Milagro / DPPI

The most remarkable grand prix career – in Formula 1 or MotoGP – came to an end at Valencia, Spain, at 2.42pm on November 14.

Valentino Rossi finished his 432nd GP in 10th place, the 42-year-old Italian going down fighting at the end of a mostly grim final season in MotoGP.

Rossi, who dazzled GP racing for more than two decades, had been in freefall during his final few seasons, due to machinery issues and the fact that time waits for no man, not even a superman.

So let’s focus on his distant glories, not his recent failures.

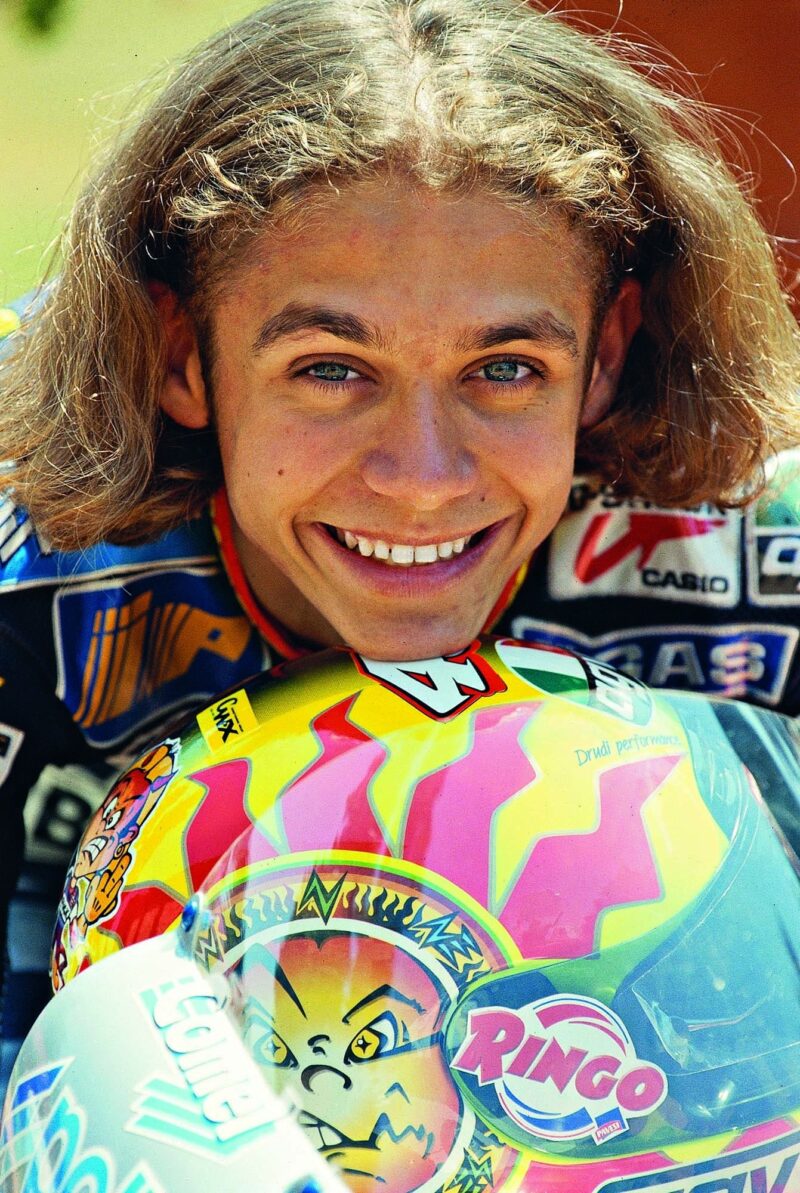

Rossi in his pomp was unique – one man transforming an entire sport with his speed and his joie de vivre. Until he arrived in the spring of 1996 motorcycle racing was a mostly dour, macho pursuit, not so much something to be enjoyed but endured – pitiless two-stroke engines, dead eyes and broken bones.

Somehow Rossi changed all of that, all on his own. True, riders still break bones, and worse, but modern MotoGP events are joyful affairs, full of colour and clamour, a rock and roll petrolhead party.

All this began in the late 1990s as a new breed of race fan flocked to racetracks to see the clown prince in action, wowing the crowd and performing outlandish post-race theatrics which, in his own words, “switched on the emotions of normal people”.

1997, at 18 years old

Rino Petrosino/Mondadori via Getty Images

For example, my girlfriend at the time watched the 1997 Japanese GP from home in London while I was at the track. Rossi led the 125cc race by a few metres until he got too greedy with the throttle when exiting Suzuka’s chicane on the penultimate lap and got spat off.

He landed heavily, sat dazed on the grass for a while, then limped back to pitlane, all the time grinning and waving to the crowd.

“I thought I could win,” he told us that afternoon. “Now I just think I’m an idiot.”

“The truth is that no bike in the world can match a two- stroke 500”

My girlfriend – to whom motorcycle racing meant nothing – became a fan that day and millions of other girlfriends, grannies and grandads followed, like children in thrall to the Pied Piper.

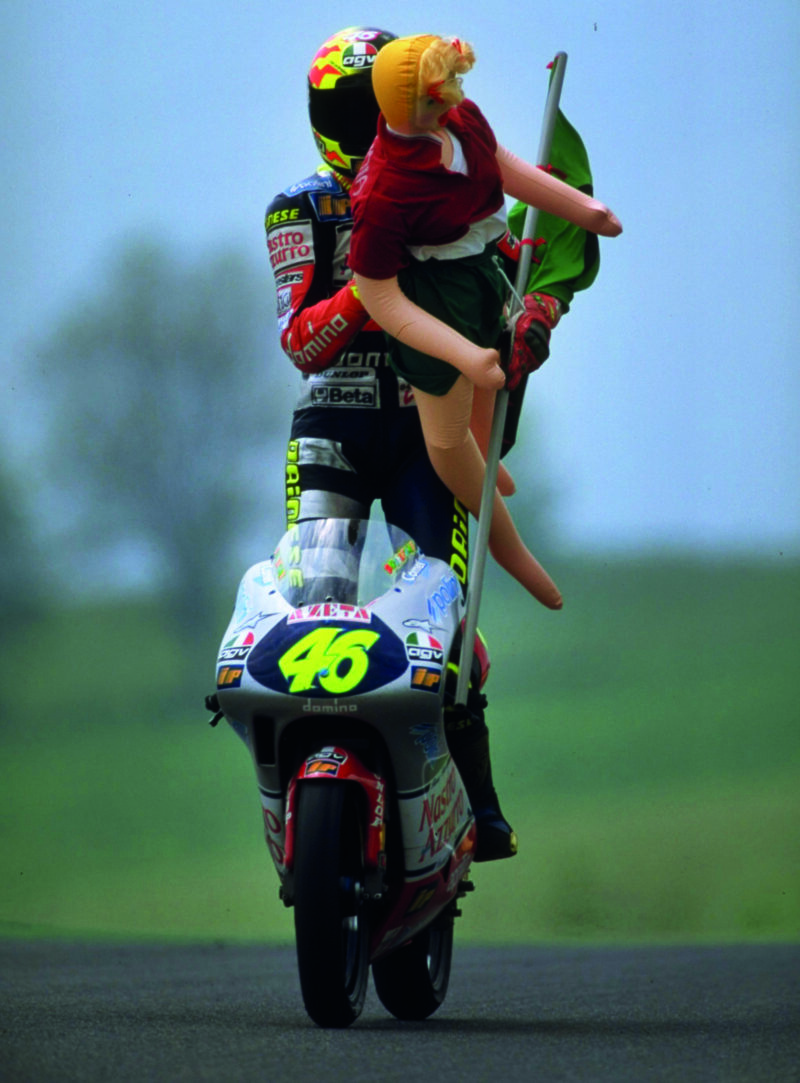

A few months later Rossi won the Italian 125cc grand prix at Mugello, his first victory at the venue which later became his holy of holies, the hillsides surrounding the track turned yellow by his legions of fans dressed in VR46 merch. That day he rode his victory lap with a blow-up doll strapped to the seat hump of his Aprilia, the words ‘Claudia Schiffer’ scrawled across the doll’s body.

This was a deliciously cheeky dig at Max Biaggi, Italy’s haughty reigning 250cc world champion, who had been making sure he was seen out and about with supermodel Naomi Campbell.

‘Claudia Schiffer’ hitches a ride at Mugello in 1997

Rossi and Biaggi became bitter enemies and in 2001 duelled for the premier 500cc world championship. During the Suzuka race Biaggi elbowed Rossi onto the grass exiting the guardrail-lined 120mph sweeper that takes riders onto the start/finish. Two laps later Rossi outbraked Biaggi’s Yamaha into Turn 1 and gave him the finger. Four months later Rossi won the title and Biaggi never really bothered him again.

“Rossi didn’t invent the warrior style of racing, but he globalised it”

Of course, none of Rossi’s fun and frolics would’ve been possible if his riding talent hadn’t been otherworldly, taking him to more premier-class grand prix victories than anyone else in history.

His career statistics are mind-boggling: 432 grand prix starts across three categories over 26 seasons, 115 victories (89 in the premier 500c/MotoGP class, 14 in 250cc GPs, 12 in 125 GPs) and a total of 235 podium finishes, including a tantalising 199 in the premier class.

For the first dozen or so years of his GP career Rossi was mostly unbeatable. Over 13 seasons he won nine world championships: one 125cc, one 250cc, one 500cc and six MotoGP. There were bad times, of course, but he always bounced back.

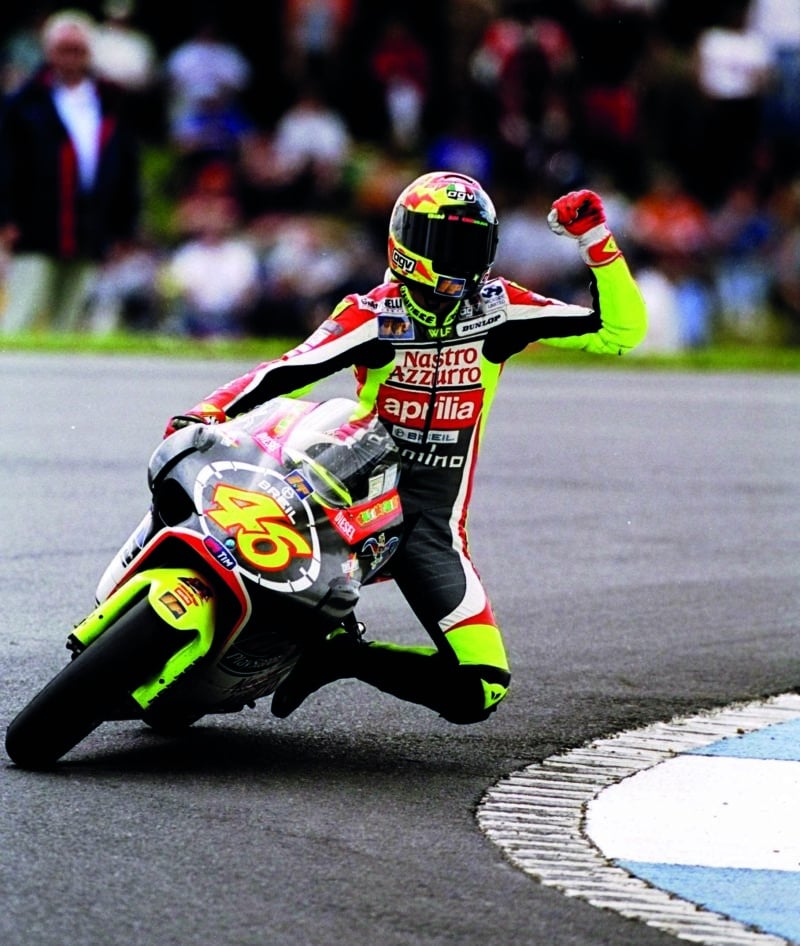

In 2002, the premier class was renamed MotoGP – and Rossi was unstoppable

Impressing the Brits at Donington Park midway through the 1999 season taking a fourth of nine wins

Michael Cooper/Allsport

Still smiling after all these years

Despite his speed, Rossi didn’t rule motorcycle racing by creating radical new riding techniques, as ‘King’ Kenny Roberts had in the late 1970s (sliding the rear tyre) and Marc Márquez did in the last decade (sliding the front tyre). What he did was bring an artist’s approach to the science of racing, perfecting each process, like Jimmy Page playing guitar or David Bowie writing lyrics. (This analogy isn’t entirely out of place – Rossi was born in 1979 but his favourite bands are 1970s rock bands.)

“For me the racing line is like a poem,” he once said.

Rossi built his legend in the final two years of the 500cc class, riding evil half-litre two-strokes that made close to 200hp, via a perilous torque curve and with no traction control. These were cruel weapons, responsible for ending the careers of the three riders who had ruled the sport immediately before him: Wayne Rainey,

Kevin Schwantz and Mick Doohan.

Rossi has raced as No46 – a number often used by his father Graziano, who himself was a world championship bike rider from 1977-82

David Ramos/Getty Images

“The simple truth is that no bike in the world can match a two-stroke 500,” he said later. “I loved its violent character – the front tyre never on the ground and the rear tyre all over the place. Either you rode her or she punished you. There was no middle ground.”

Rossi entered the premier class with Honda, riding its NSR500 two-stroke, and stayed with the company in 2002 and 2003, riding its sublime 990cc RC211V four-stroke, still considered the greatest GP bike of all time by racing connoisseurs.

The first two seasons of the new four-stroke MotoGP championship were his strongest, with an average of 22 points per race from a possible 25. However, the brilliance of Honda’s five-cylinder vee caused its own issues. The RC211V’s utter dominance (29 victories from 32 races in 2002 and 2003) convinced Honda that the machine mattered more than the man. Rossi disagreed, so off he went in a huff to ride Yamaha’s hopeless YZR-M1 (two wins in 2002, zero in 2003).

Here was proof that Rossi preferred a challenge to an easy cruise to gold and glory.

Against all the odds, together with archly pragmatic chief mechanic Jeremy Burgess and Yamaha engineers, Rossi fixed the M1 in a matter of days. At the 2004 season-opening race he beat Biaggi, now riding an RC211V, by two tenths to become the first (and so far, only) rider to win back-to-back premier-class races with different brands of motorcycles.

Rossi’s unlikely Yamaha successes quite rightly elevated him to the status of motorcycling deity. How could anyone do what he had done? But he had done it, although not always with the gentlemanly poise of his days at Honda.

Rossi’s last MotoGP win came in 2017 but in 2018, when this photo was taken – at Phillip Island, Australia – he was still among the frontrunners, finishing the season third with Yamaha

An inferior machine required nefarious tactics. Rossi had his elbows out whenever he fought for victory aboard the M1 and woe betide anyone who wanted a fight.

Rossi didn’t invent the warrior style of racing, but he certainly globalised it. Whenever he got nasty with his rivals millions watched and applauded,

including a very young Márquez, sat at home with his mum and dad, absorbing every move and every detail.

In fact Rossi’s ruthlessness had always been there. No one gets to the top of pretty much any endeavour without a ruthless streak, without that willingness to see rivals fall off the ladder, while they keep their eyes looking upwards and take the next step towards the top.

Rossi had won his first two world titles as a teenager with Aprilia, a small Italian brand, where the family feeling was strong. However, even then the shiny, happy youngster had that ruthless edge, which in those days he saved for behind closed doors. Twice during his three seasons as an official Aprilia rider he threatened to quit the factory if his bosses didn’t do exactly what he wanted.

During his first seven seasons at Yamaha Rossi fought against faster bikes and then a new breed of faster rider, most notably Spanish team-mate Jorge Lorenzo and Australian Casey Stoner.

“They are like sharks circling around me,” he told journalists while fighting for his final world title in 2009. “If I am not strong I know they will eat me in one bite. They look at me with a little bit of blood flowing and maybe they think, ‘OK, now is the time.’”

Rossi fully understood that age and guile can still beat youth and a bad haircut, for a while at least.

Eventually Lorenzo’s presence in the Yamaha garage drove him out and into the arms of Ducati instead, which turned out to be arguably the biggest mistake of his career. He spent two years with the Italian manufacturer, but didn’t manage to win a single race.

“Sometimes you have the feeling that you’ve wasted your time,” he said at the end of those two seasons.

Yamaha took him back in 2013, Rossi slowly building to his epic title challenge in 2015. Already in his late thirties he came within five points of beating Lorenzo for the championship. Rossi believed that some of his rivals – Lorenzo, Márquez and his Honda team-mate Dani Pedrosa – had conspired to prevent him from winning a tenth world title, but in truth he wasn’t quite fast enough. He won four races to Lorenzo’s seven.

After that Rossi’s results collapsed. Not so much because he was too slow, but because in 2016 MotoGP switched from Bridgestone tyres to Michelins and from tailor-made factory software to spec Magneti Marelli software. Yamaha struggled more than the others to adapt its M1 to this new technical reality. Even now Yamaha isn’t quite there, relying upon the talents of its latest young recruit, Fabio Quartararo, to ride around the electronics to win the 2021 MotoGP crown, its first of the Michelin/Magneti Marelli era.

Meanwhile Rossi finished his final season 18th of 21 full-time riders, his 2020 and 2021 results further compromised by a new rear slick, which didn’t fit his riding style.

At the Spanish Grand Prix, May 2021

A gloomy end to a previously glittering career? Not really.

Rossi isn’t stupid. If he already knew in 2009 that the youngsters were coming after him, he knew what the future held. But he needed the thrill of motorcycle racing too much to quit, until he had no real option to continue.

“I was worried about Valentino when he was finishing eighth or ninth,” said Burgess (who Rossi unwisely sacked at the end of 2013) a couple of years ago. “But he was quite at ease with himself at his age and where he was in his life, so he wasn’t going to panic and go ballistic trying to take himself back to first place.”

Mechanic Alex Briggs, who worked with Rossi for 21 seasons, also understood the ongoing decline.

“Valentino isn’t 20 any more,” he said recently. “Think about it, you go on some mad circus ride when you’re 20 and it’s fun. Get on that same ride now and you go, ‘Whooaaa!’ Why is that? It’s just your brain.”

The scenes in the Petronas garage after Rossi’s final race in Valencia on November 14

Rossi won his final MotoGP race at Assen in 2017, so he was winless for his last four seasons. And yet couldn’t kick the habit, even after he came close to death during the 2020 Austrian GP at Red Bull Ring, when a fallen, airborne motorcycle flew past at high speed, just centimetres away.

“It was so scary, terrifying,” he said after taking the restart of the red-flagged race 40 minutes later. “Taking the restart was a very difficult moment, but I think I didn’t have any choice because I don’t want to say ‘Ciao, ciao!’ to everybody and go home yet.”

The bike that came so close to killing him belonged to Franco Morbidelli, the first rider signed by Rossi’s VR46 Riders Academy to foster young Italian talent. Morbidelli was the first VR46 rider to win a world title and next year there will be three or four VR46 riders in MotoGP, plus VR46 teams in all three classes: MotoGP, Moto2 and Moto3.

The end of a chapter, but what’s next for Rossi and his adoring fans?

Rossi will therefore split his time between his MotoGP commitments and his nascent car racing career, driving a Kessel Racing Ferrari 488 GT3 in sports car events. Rumours suggest he may also play a part in Ferrari’s 2023 Le Mans Hypercar project.

The man himself is keen for his move into car racing next year, wherever it may be. “Next year I will race GT, I still don’t know which championship, because it can be the WEC but can also be European Le Mans Series or GT World Challenge,” he said ahead of his final MotoGP race. “I need to understand also my level and my speed. I’d like to race LMP2 or the Hypercar… but there the level of the drivers is very high, so I don’t know if I’m fast enough. We will try to understand next year.”

Will MotoGP ever have another rider like Rossi on the grid? It is highly unlikely in any of our lifetimes.

A day of emotion as Valentino Rossi looks back at his last ride

Reunited with all the bikes from his career in Valencia.

Rossi was satisfied to finish 10th and ended the season in 18th position

Valentino Rossi’s last race was better than anyone had expected, him included: “It’s very easy when you’ve said, ‘OK, I’m stopping,’ to give up but after Portugal [his penultimate race] I spoke with my team and I said, ‘In Valencia we have to give the maximum because it’s the last race and I don’t want to arrive last’. It was very important to make a good result. It wasn’t easy, but I wanted to try, because the most important for me was to be strong in the race. I felt the motivation and concentration like I had to play for the championship, because the last race is very important – you will never forget it.

“It was a great emotion for me. I rode very well, I never made any mistakes and I gave the maximum from beginning to end. I finished in the top 10, so this was one of my best races of the season and I enjoyed it. It means I closed my career with the top 10 riders in the world and this is so important for me. After the race we did some serious casino and we enjoyed it, like I’d won the championship. It was something I’ll never forget.”

The Doctor: what a ride

Born: February 16, 1979

1990: Begins his career in karts, winning the regional championship in Italy in his first year. He raced on four wheels until 1992.

1993: Competes in his first bike race, as part of the 125cc Italian Sport Production Championship.

1994: Wins the Italian Production title on a factory Cagiva Mito.

1995: Wins the Italian 125cc title with Aprilia, finishes third in the European championship.

1996: Makes his motorcycle grand prix debut in the 125cc world championship, riding for Aprilia. Finishes ninth in the points.

1997: Rossi’s first world title arrives as he scores 11 wins and 13 podiums for the 125cc Aprilia factory team.

1998: Remains with Aprilia for his debut in the 250cc division. Wins five times on his way to second in the championship. Takes the title with nine wins the following year.

2000: Rossi switches to Honda and graduates into 500cc racing. Two wins leaves him second in his first year, before the title again falls his way in year two, with 11 victories.

2002: Motorcycle racing’s premier class is renamed MotoGP and Rossi becomes its leading light, taking back-to-back championships for Honda, amassing 20 wins across the first two years and 31 podiums.

2004: Moves to unfancied Yamaha and immediately makes the team a winner, claiming back-to-back titles again. Becomes the only rider to win back-to-back MotoGP races on different brands of bike.

2009: Scores his sixth, and final, MotoGP crown, with six wins for Yamaha, narrowly beating Lorenzo.

2017: Rossi’s final MotoGP win (his 76th) comes in the Dutch GP at Assen.

2021: After four tough and winless years, Rossi retires after the MotoGP finale in Valencia.