Racing's toxic rivals

The adrenaline is coursing through your veins when, from out of nowhere, you feel a jolt, your car slides and your race – maybe even your world championship – is over. That’s when the anger erupts, because you know who’s responsible. Simon Arron shakes a fist at racing’s rancid relationships, where red mist and retribution were part of the entertainment

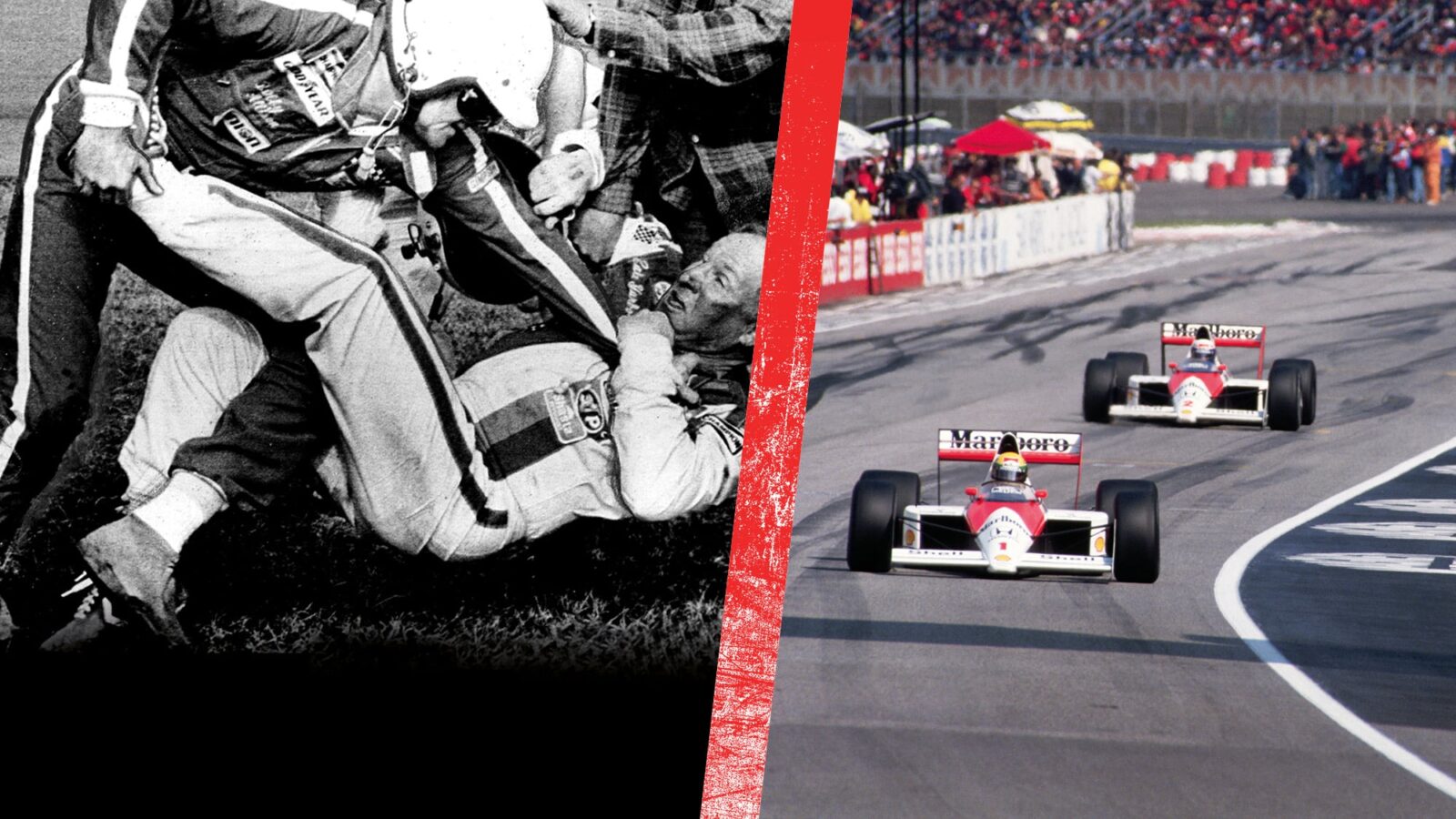

Team-mates at McLaren, but there was no love lost between Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost. Opposite: Fight, fight, fight! NASCAR’s Bobby Allison, left, and Cale Yarborough

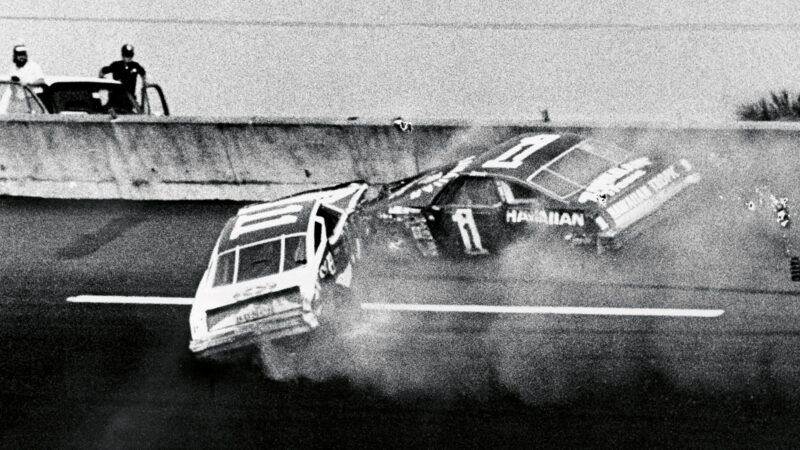

February 18, 1979. Notionally the focus should have been on Richard Petty as he extended his Daytona 500 victory tally to six in the first full NASCAR race broadcast live on TV, but there was an alternative headline. Petty won because Cale Yarborough and Donnie Allison crashed while disputing the lead on the final lap – and a brawl ensued after their crumpled cars came to a halt on the infield. Bobby Allison was involved, too – and he’d only stopped to offer his younger brother a lift back to the pits. “I think it made a lot of fans for the sport,” Yarborough said years later. “It got people’s attention. I think it’s one of the best things that ever happened.”

That spur-of-the-moment conflict shifted NASCAR from the sports section of newspapers to the front, but motor racing has always thrived on the attention bred by rivalries that become toxic, whether spontaneously – as in the instance above – or more durably, such as the feud between Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost, which began when they were team-mates at McLaren but continued until the Frenchman retired several seasons later. The triggers can be manifold – on-track or personality clashes, competitive pressures, throwaway comments that are purposely provocative or else misconstrued, perceived injustices – but the outcome is invariably effervescent.

Tempers flared after this crash between Donnie Allison (No1) and Cale Yarborough on the final lap of the Daytona 500 in 1979 – live on TV. NASCAR became headline news

These things extend to the pit counter, too – most frequently of late between Christian Horner and Toto Wolff, team principals of F1 title protagonists Red Bull and Mercedes. After their drivers Max Verstappen and Lewis Hamilton collided at Silverstone, Wolff went to see the stewards –a move Horner equated to “trying to lobby a jury while they reach their verdict”. In Azerbaijan, Wolff described his rival as “a bit of a windbag who wants to be on camera” after the two had taken contrary stances on the art of wing design. Then came Wolff ’s goading fist-shaking at the cameras after Hamilton’s epic recovery drive to win the Brazilian GP, having copped what was effectively a 25-place grid penalty for a defective DRS system and an engine change. This one is likely to rumble on.

Ever since the Allisons vs Yarborough punch-up, NASCAR has featured more than its fair share of flashpoints – veteran Kevin Harvick said he was “ready to rip somebody’s frickin’ head off ” after a postrace shoving match with Chase Elliott at Bristol, Tennessee in September – and also nurtured probably the most violent conflict ever seen in mainstream motor sport.

Talladega, 2009

Carl Edwards and newcomer Brad Keselowski first tangled at Talladega in 2009, when they touched at the final corner and the former’s car was launched into the debris fencing as Keselowski came through to win. The following year, they collided in the early stages of a race at Atlanta. Edwards ended up in the wall, but later rejoined more than 150 laps in arrears. With three laps to go, Edwards clipped Keselowski and his nemesis’s car flipped into the fence.

Later in the season, while duelling for the lead on the final lap of a Nationwide [second-tier] race at Gateway, they came together again. Edwards carried on to win, while Keselowski bounced off the wall, triggered a multiple pile-up and sustained rib injuries that required a hospital visit. Edwards said in Victory Lane, “I couldn’t let him take it from me –I had to do what I had to do.” NASCAR decided it didn’t like what he’d done, fined him £16,000 and stripped him of 60 championship points. Both were subsequently put on probation, to quell the feud before anybody was seriously hurt, and calm was finally restored.

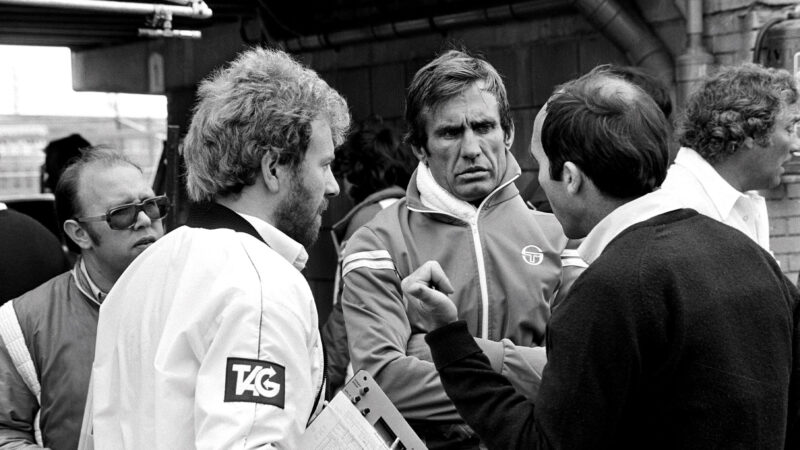

Mario Andretti, right, saw red against AJ Foyt, left, early in his career but learnt from it

Mario Andretti admits he once considered retribution. “There was some tension between AJ Foyt and I outside the cockpit,” he said, “but on the track he was always correct. I learnt a big lesson early on, in a sprint car race in ’64. All the big guns were there, but I took pole and Foyt started fifth. He jumped the start, caught me, spun me out and I lost a lap. I should have parked it but I wanted to get back up to Foyt and spin him out. With a lap to go I was behind him and then the chequer came out, he’d won the race, and that was a blessing. What a jerk I would have been if I’d spun him off. It would have haunted me the rest of my life and I decided that never, ever would that be a part of my make-up, to have revenge on the track.”

Andretti leads Foyt, Indy 150, 1970

Not all have followed his example and questionable track etiquette is nothing new. Looking back on his career in 2011, Stirling Moss cited inaugural world champion Nino Farina as a particularly challenging adversary. “He didn’t give you any quarter at all,” Moss said. “He practised some of the driving ethics we’ve become used to in modern motor sport, but he was doing it against a backdrop of 1950s safety standards.”

Lewis Hamilton was criticised by some for his tactics during the 2016 Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, when he drove as slowly as possible while leading in an ultimately unsuccessful bid to make Mercedes teammate and title rival Nico Rosberg vulnerable to an attack from the cars behind. On several occasions, Hamilton ignored radio instructions to increase his pace. In reality he’d done nothing wrong; he was simply using the best tactic available to tilt the balance of power in the title race. Such disobedience was hardly new; at Monaco in 1937, Manfred von Brauchitsch had likewise ignored Mercedes team orders to let teammate Rudolf Caracciola through, and is said to have responded to racing chief Alfred Neubauer’s instruction by sticking out his tongue –a prototype, perhaps, for sullen radio replies of the modern age.

Will Hamilton and Leclerc share a Hamilton and Rosberg resemblance?

Getty Images

Quicker, Lewis!

Although the relationship between Hamilton and Rosberg was frequently tense and occasionally physical (though never deliberately so), it was only fractionally as querulous as some of those a quarter century beforehand. At Monaco in 1989, Derek Warwick was on a qualifying lap he thought would be good enough for the second row… until Arrows team-mate Eddie Cheever baulked him. A wheel-banging match ensued, at which point Warwick called upon some tricks he’d learned during his formative years in stock car racing. As he told Motor Sport in 2008, “I just drove him into the barriers at the Swimming Pool.” The two had to be kept apart when Cheever returned a few minutes later, but a handshake at the following race in Mexico patched things up.

Mind games at Monaco in 1988 – but between them, Prost and Senna gave McLaren 15 out of 16 wins that season.

Charles Knight/Shutterstock

Nothing, however, has been quite as intense as Senna vs Prost, which commenced at McLaren in 1988. After a passably cordial dawn, their relationship faltered during the Portuguese Grand Prix.

With the title’s destiny in the balance between them, and having been beaten away from pole by his team-mate, Prost attempted to reclaim the lead at the opening lap’s conclusion. Reporting the incident in Motor Sport (November 1988), David Tremayne wrote: “What Senna did next was to cause the real fuss of the meeting, and burn itself into the memory of Prost’s mental computer. As he drew alongside, Senna simply lunged at him. No other words accurately describe the incident. And in the lunge, Prost was squeezed perilously close to the wall. Indeed, March team manager Ian Phillips had to pull back his pitboard to avoid striking Prost’s helmet. He was not alone in being incensed by the Brazilian’s tactics. ‘I knew I had to keep my foot down because at one stage we had our wheels interlocked,’ said Prost afterwards, anger still simmering. ‘If I had eased off, we could have caught wheels and then who knows what would have happened? If that’s how he wants to win the championship, I’m not interested. I don’t want any part of it.’”

Senna received a slap on the wrist from officials. The two drivers later convened to discuss the incident privately and by the following race at Jerez they appeared to be reconciled, leastways on the surface.

Storm clouds at the 1989 Australian Grand Prix

The uneasy truce crumbled early the following season, at Imola. Tremayne again (Motor Sport, June 1989): “The real story was the manner in which Alain Prost stormed off after the race, not prepared to speak to anyone. Unbeknown to most, and at Senna’s suggestion, he had agreed to a pact wherein neither would overtake the other during the opening laps, to avoid the risk of jeopardising their title chances. Senna saw nothing wrong in the fact that he’d passed Prost despite the agreement. Prost was livid, felt betrayed, and would later say Senna was not honourable…”

“Prost was livid, later saying that Senna was not honourable”

Neil Oatley was Prost’s race engineer. “Things really deteriorated after that,” he says, “and they didn’t speak for the rest of the year. Debriefs would involve me, Ayrton’s engineer Steve Nichols, [technical director] Gordon Murray and the two race drivers. Ayrton would ask me things about Alain’s car and Alain would speak to Steve about Ayrton’s, but they didn’t talk directly to each other.”

The pair did eventually clash on track, a slow-speed tangle at the Suzuka chicane settling the 1989 title in Prost’s favour. It would be the Frenchman’s penultimate start for McLaren, the team that had once been moulded around him. He switched to Ferrari and, one year later, the title would again be settled amid controversy at Suzuka. Angered that race officials refused to switch his pole position to the cleaner side of the track, and that Prost predictably made a better start, Senna simply torpedoed his rival, taking both out of the race at the first turn and securing a second world title in the process.

He denied culpability at the time, but owned up a year later at the same venue, where he had just clinched a third title and his arch-rival was about to be sacked after criticising a Ferrari team in the throes of political turmoil.

“[FIA president] Balestre gave an order not to change [pole position],” Senna reflected, “so I said to myself, ‘All right, tomorrow, if Prost gets the jump and beats me off the line at the start, because I’m in the wrong position, at the first corner I’ll go for it. And he had better not turn in, because he’s not going to make it.’ And it just happened, I guess. I just wish it didn’t happen. We were both off and it was a s*** end of the championship.”

Despite everything, the two were eventually reconciled. Ferrari hadn’t been competitive in 1991, Prost took a sabbatical the following season and swept to a fourth title when he returned with the dominant Williams-Renault team in ’93. At the end of that campaign, the two were on the podium in Australia and Senna pulled Prost up to join him on the top step. With competitive tension dissolved, the two would become firm friends during the final few months of the Brazilian’s life.

Alan Jones, left, and team-mate Carlos Reutemann at Long Beach

Frank Williams, right, perhaps explaining to Reutemann how the ‘contract’ worked, with Neil Oatley, left

Oatley had also occupied a ringside seat at Williams in 1981, when he engineered Carlos Reutemann alongside defending world champion Alan Jones. The gloves came off two races into their second season together, when Reutemann ignored an instruction to let his team-mate through during the Brazilian Grand Prix.

“Alan had been comfortable with Clay [Regazzoni] as his number two in 1979, because he knew he could beat him,” Oatley says. “He realised Carlos might disturb that equilibrium. They were very different characters and there was no way they were going to be drinking buddies. Carlos had quite a tricky start to his first season with the team and I did hear Alan describe him as an ‘expensive Clay Regazzoni’, albeit not to Carlos’s face!”

Jones won the title in 1980 and, contractually, was the team’s number one – so much so that Reutemann’s deal obliged him to cede if the two were running first and second, in close proximity, as a race drew towards it conclusion.

“I can’t remember the precise number,” Oatley says, “but if the gap between them was less than a few seconds then Carlos was supposed to let Alan through. He led the opening race of 1981 in Long Beach by about 3.5 seconds and I know he had the contracted number in his head. He was trying to stretch his lead beyond the cut-off point and ran wide, so Alan overtook him before Carlos was required to concede. I thank that played a part in what happened in Brazil. Although Carlos knew what he’d signed, he felt that by giving up a place he would no longer be a racing driver. He was struggling with that as a concept.”

In his 2017 autobiography, AJ: How Alan Jones Climbed to the Top of Formula One, Jones wrote: “I was furious. I could have challenged him many times. If it wasn’t for the agreement I would have done. I was faster and felt I could easily have won, and without the agreement I would have slipped it down the inside, or I would have had a go somewhere.

“The agreement was there to stop us taking risks with each other. Carlos didn’t abide by the agreement he signed. That’s the thing that upset me. I didn’t talk to Carlos after the race. I just said to Frank, ‘All bets are now off.’”

Oatley: “I don’t recall any overt animosity or frostiness of the kind we saw later with Prost and Senna. They might have said ‘hello’ in the morning, but from that point I don’t think there were many other conversations between them. Alan basically just discounted Carlos from his thoughts – as far as he was concerned it was now a one-car team.”

“I think Jason goes into attack mode whoever he is against”

Sidelined from the championship race by unreliability, Jones went to the Las Vegas finale with no intention of helping Reutemann in his title battle against Nelson Piquet and outsider Jacques Laffite. Quite the opposite, in fact.

Reutemann took pole position ahead of his Williams team-mate, who decided there was scope for mischief. “I thought I’d play with him,” Jones wrote. “Have you seen where pole is? It’s just a disgrace, there’s s*** everywhere. I don’t know how you’re going to get off the line.’”

Reutemann subsequently requested a switch, which was granted. Transferred to the favourable side of the circuit, Jones took an immediate lead he would never relinquish – and went on to lap his nemesis as Reutemann slipped ever backwards; he finished outside the points and behind Piquet in the title race.

Jones left Williams at the campaign’s end to return to Australia, though he would subsequently make a couple of F1 comebacks; Reutemann stayed for 1982, but quit abruptly after two races and later forged a successful political career. Jones’s final thoughts on the matter? “It was kind of appropriate he became a politician, where his dishonesty could work for him.”

Others are more prepared to let bygones be just that.

The British Touring Car Championship has conjured its fair share of controversies over time, mostly as a consequence of regulations that guarantee close racing, in which a degree of contact is almost inevitable, but with the occasional grudge match thrown in.

Honda’s Matt Neal alongside Jason Plato’s Silverline Chevrolet at Brands Hatch, 2011

Matt Neal and Jason Plato had an enduring rivalry, which reached boiling point after some jostling during the final moments of qualifying at Rockingham in 2011. Having taken pole, Plato flicked a finger at his rival, who strode across and threatened the more substantial alternative of a fist. Perhaps wisely, Plato kept his helmet on.

Both were fined £1000, handed three disciplinary points and given six-place grid penalties, suspended for the balance of a season in which Neal was crowned champion.

“If you’re in it for long enough, you fall out with an awful lot of people,” Neal says. “The Rockingham incident grabbed the most attention, but by then we’d been going at each other since about 2005.

“Rightly or wrongly, I’ve always taken the attitude that if somebody hits me, I’m going to hit them back. I don’t believe in all the namby-pamby stuff; if you give it, you’re going to get it back – and then hopefully they won’t do it again. I think Jason goes into attack mode whoever he is against.

I probably reacted harder and more often than anybody else, so it got out of hand. I can laugh about it now, but it didn’t seem funny at the time. There was a bit of a eureka moment at Donington Park a few years ago when we spent almost a whole race side by side without touching each other at all – and there are quite a few goons out there at the moment who can’t do that, because they are out of their depth. At least with Jason, nine times out of 10 when he hits you know it’s because he meant to! I’m pleased to say we’re friends again now.”

‘Flying testosterone’ with Mark Blundell and Bertrand Gachot

The 1985 British Formula Ford 1600 Championship was one of the toughest on record, featuring future grand prix drivers Damon Hill, Johnny Herbert, Mark Blundell, Bertrand Gachot and several others who were at least as quick at that stage of their careers.

“I was almost arrested for a breach of the peace at Castle Combe that year,” Blundell says, “because a couple of local policemen happened to be in the paddock.

“Sospiri let the first two through, then obstructed his team-mate”

“Bertrand had continually tried to put me off onto the wet grass – as far as I was concerned he was trying to shove me into one of the concrete marshalling posts. We were young at the time, there was lots of testosterone flying around and I was fuming. I went straight over to him afterwards and suggested he take off his helmet, which he wouldn’t, so I attempted to fit my fist through the visor aperture, which didn’t work.

“I still maintain, though, that the racing that year was the best I ever experienced – and the two of us get along very well nowadays.”

For supreme petulance, look no further than the final round of the 1991 FIA Formula 3000 Championship at Nogaro, France, where Damon Hill’s chances of taking second place were compromised by Middlebridge EJR team-mate Vincenzo Sospiri.

“We’d had a really tough season, the first in which Avon had introduced radial tyres, and they didn’t suit our Lola,” says Ray Boulter, who was team manager. “We did about 6000 miles of testing and tried everything, but nothing worked.

“For Nogaro, we decided to hire a Reynard for Damon. It cost £15,000 and we contacted Eddie Jordan, who was managing Vincenzo, and asked whether he’d like to do the same, but he decided against it.”

Damon Hill leads F3000 team-mate Vincenzo Sospiri in 1991, when both were in Lolas. The Italian reacted badly when Hill later switched to a Reynard

Hill qualified third, behind title contenders Christian Fittipaldi and Alessandro Zanardi, while Sospiri languished in 20th. When the three leaders came up to lap Sospiri, he obligingly let the first two through – and then obstructed his team-mate for a couple of laps, driving him off the road at least twice for good measure (though Hill still finished third).

“After finally getting through, Damon came on the radio and told us we’d best make sure he didn’t see Sospiri afterwards,” Boulter says, “so we ushered him to the podium while Vincenzo made himself scarce. He claimed he hadn’t seen Damon because he’d lost one of his mirrors, but I later saw footage that showed he’d torn it off himself, after the incident!”

Citroën’s Sébs – Ogier, left, and Loeb – were bitter rivals in the 2011 WRC; Ogier departed to VW for ’12

Despite the absence of wheel-to-wheel combat, rallying is also capable of brewing searingly bitter feuds. It was perhaps inevitable that Sébastiens Loeb and Ogier would cross swords during a full season together at Citroën in 2011: a multiple world champion against his future successor, the pair of them linked by nationality and a raging desire to win. Things reached a head in Germany, where Citroën issued an order that the two should hold station at the end of the first day, with Loeb ahead. Ogier wasn’t happy, and described it as “justice” when his team-mate was delayed by a puncture on day two. Loeb went on to take the championship while Ogier took the rally and decamped to VW, with whom he’d win the first four of his seven titles to date.

Perhaps the most combustible partnership was François Delecour and Gilles Panizzi at Peugeot. On the 2000 Rallye Sanremo, an interviewer mentioned to Delecour that Panizzi had been practising stages illegally, before the recce began. “It’s not my problem,” replied Delecour.

Light touchpaper… Peugeot’s François Delecour and Giles Panizzi in 2000

During a subsequent service halt, however, it became clear that it was a bit of a problem as Peugeot’s crew had to intervene to prevent Delecour confronting Panizzi. An enraged Delacourt then stormed into his motor home. The dispute did not affect either driver’s speed: between them they won seven out of the eight special stages.

Not for the first time, a bitter rivalry had spurred drivers on to greater things.