“Remember, nothing was power-assisted, so steering and braking took it out of you, and it was so important to be precise in those long, fast corners. One mistake and you would be in the trees… or a house. The track was not so wide then, and I tell you, it was fast, sometimes scary, no way two abreast at Raidillon. You don’t make a mistake there or you are going to crash. On the big straight after Eau Rouge and Raidillon it was easy 300km/h [186mph], no chicane like now at Les Combes, the trees were so close, the car would jump in the air at the top. On the way down to Stavelot there were houses; you had to be so precise, millimetre-perfect. If you hit the house you were not coming back. The most dangerous place was Blanchimont. I felt like I would s**t myself, you were right on the edge there. This Spa was not like today, not at all.”

Sitting below a poster of the 1955 Mille Miglia, and a bottle of champagne celebrating 70 years of Ferrari, Merzario moves on to the Targa Florio, where he was twice a winner in 1972 and 1975. “You know, my secret for road races was my memory. One lap in practice and I had a film of the circuit in my head. It was the same with the Nordschleife, nobody could believe it. Most important was to know all the places to go fast, the places where I could hurt myself, and where the surface was not so good and what you might hit. That’s the secret.

“The speeds were not so high, a lap was about 33 minutes, and when Helmut Marko was chasing me in ’72 he set the lap record, his average speed only 80mph. The challenge was not just the mountain roads, it was also the spectators. They stood sometimes on the track so you had to know exactly where to place the car – they were not going to move. The roads were not closed for practice so there were sheep, goats, donkeys, scooters, people walking around, and you never knew what might be around the corner. Absolutely not possible to have a race like this today, it would be crazy, far too dangerous now.

The Ferrari 512S was a tiring car to drive; the Porsche 917 was easier. Merzario takes to the air at the Nürburgring, 1970

“Always I was fast on road courses, from the early days with Abarth on mountain climbs, and I won the Sardinia Rally back in 1963 with an Alfa Giulietta, so for me the Targa was a joy, in the Ferrari 312PB in ’72 and in the Alfa Romeo T33 in ’75. You had to pace yourself, this was important, because the race is long and you need to conserve your energy. Porsche would practice for a month, studying every detail, but with Ferrari we went only for a week before the race itself. In ’72, I was with Sandro Munari, a good co-pilot and a rally driver, and we beat the Alfa Romeos, which was nice for Ferrari. Also, you know, it was a very big year for me, starting with Ferrari in Formula 1 at the British Grand Prix, and winning the European 2-litre Sports Car Championship with Abarth.

“I was working in the Abarth factory when Ferrari called. There was a summons over the Tannoy on the shop floor… ‘Merzario, telefono!’ So I took it and a man said, ‘Ferrari at Maranello, I want you to come and see us.’ It was Enzo… but I thought someone was pulling my leg, so I said, ‘Sorry, I am really busy at Abarth and I have a race at Imola coming up.’ The line went dead and I went back to work, wondering who was the prankster. After the race at Imola a man I’d never seen before approached me and said, ‘You must be at Maranello on Monday,’ at which point a journalist appeared and said, ‘I hear you are going to Ferrari.’

Merzario at a private Ferrari test at Fiorano in 1972

“So I went. When I arrived I was shown into a waiting room, sat there for nearly two hours. Then they called me in, Enzo at his desk, an accountant and a lawyer. The Old Man said, ‘I want you to race for us,’ and I explained I had a contract with Abarth. ‘Not your problem,’ he said, and offered me a huge amount of lire – too much, and I told him it was a crazy figure, I was only 24 years old. He looked at his accountant and said, ‘Merzario says it’s not enough,’ – which was typical Enzo. Anyway, I signed and had two years with the team.”

In 1972, the Ferrari B2 was a good car and, given only two starts at Brands Hatch and the Nürburgring, he impressed. He took sixth at the British Grand Prix and his first championship point, despite a long stop with a puncture, and placed 12th at the ’Ring. He was in illustrious company, the Scuderia having Jacky Ickx, Clay Regazzoni and Mario Andretti on its books at the time. The 1973 season, alongside Ickx, was a different story. The B3 was a dog and poor results triggered a political storm at Maranello.

The Ferrari 312B3 was critically off the pace at the 1973 US GP, seen here missing wings in practice

“We used the B2 for the first five races and I was fourth in Brazil, fourth in South Africa,” he says. But it was downhill from there, the B3 outclassed by the Tyrrell, the Lotus 72 and pretty much everyone else. “Fiat brought in Sandro Colombo who ordered a monocoque from John Thompson in England, but only one arrived, for Ickx, at the start of the European season. It was a mess, and in the summer Mauro Forghieri came back; he’d already designed a B3 with a big, wide nose, which the media called spazzaneve – the snow plough. Maranello was not amused. This car was put aside, but I worked with Forghieri on my car, we improved it, but things were so bad we missed some races, including the Nürburgring. So Ickx left and raced a McLaren in Germany. There was no car for me in Britain, Spain, Belgium, Sweden or Germany, so at Monza I went to see Enzo – we always had a close communication. I told him, ‘No, I cannot work with Colombo and Giacomo Caliri and all their politics, I leave at the end of the year.’

“He was furious. Nobody said ‘no’ to Mr Ferrari. After practice, he said he was taking Lauda and Regazzoni for 1974, so, I said, ‘Okay, if you want me to go to Canada and America for the last two races I will go, otherwise I don’t care what happens.’ He was like Machiavelli, the way he controlled the team, and it was always the cars that took the glory, never the drivers. When Lauda won the championship, he hated how Lauda got all the publicity and not the Ferrari car, you know? Anyway, he said ‘Okay, you’re on your own, I send one car, for you, then you leave.’ I did two laps at Monza that weekend before the suspension broke. At Mosport, I was 15th, five laps behind, Watkins Glen 16th, four laps behind.”

All in all, 1973 is not a happy memory, and Arturo had fallen out with Ickx in F1. “As a driver, he was one of the greatest, yes, but always so political, wanting everything his own way. It was trouble if he didn’t get it.”

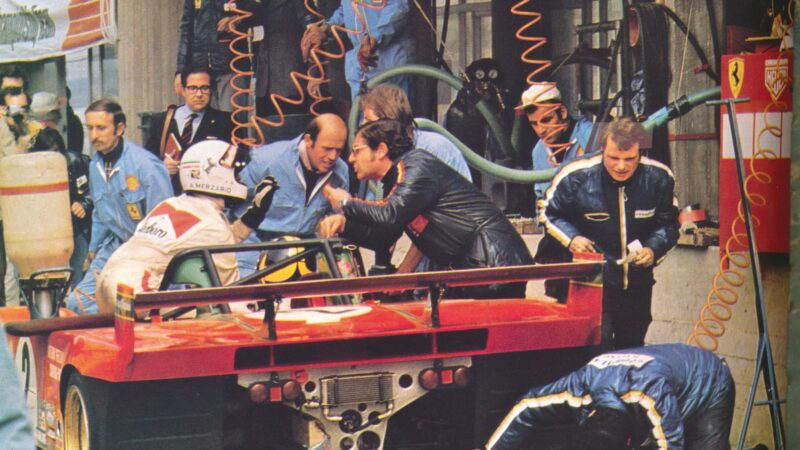

Fury in the Ferrari pitlane at the Nurburgring 1000Kms in 1973, with Arturo stating his case, left, and refusing to let go of the wheel

This animosity boiled over at the Nürburgring 1000Kms in May. Running first and second in the 312PBs, Ickx and Merzario were told to hold station at the final pitstops but the Italian had other ideas. He was catching Ickx, came up behind him, ready to take the lead, and tapped the Belgian’s gearbox a couple of times. On the pitwall, all hell broke loose. Forghieri was waving wildly and clutching a hammer, until Merzario had to come in for fuel whereupon he refused to get out of the car to hand over to Carlos Pace.

“I was so angry, I was faster than Ickx, so why should I get out? It was crazy, everyone shouting. I clung to the wheel, but they pulled me out, and I didn’t hang around, went straight to Cologne airport and home. Of course, Pace obeyed the orders, followed Ickx into second place.”

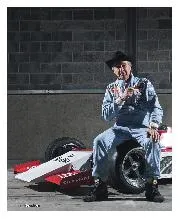

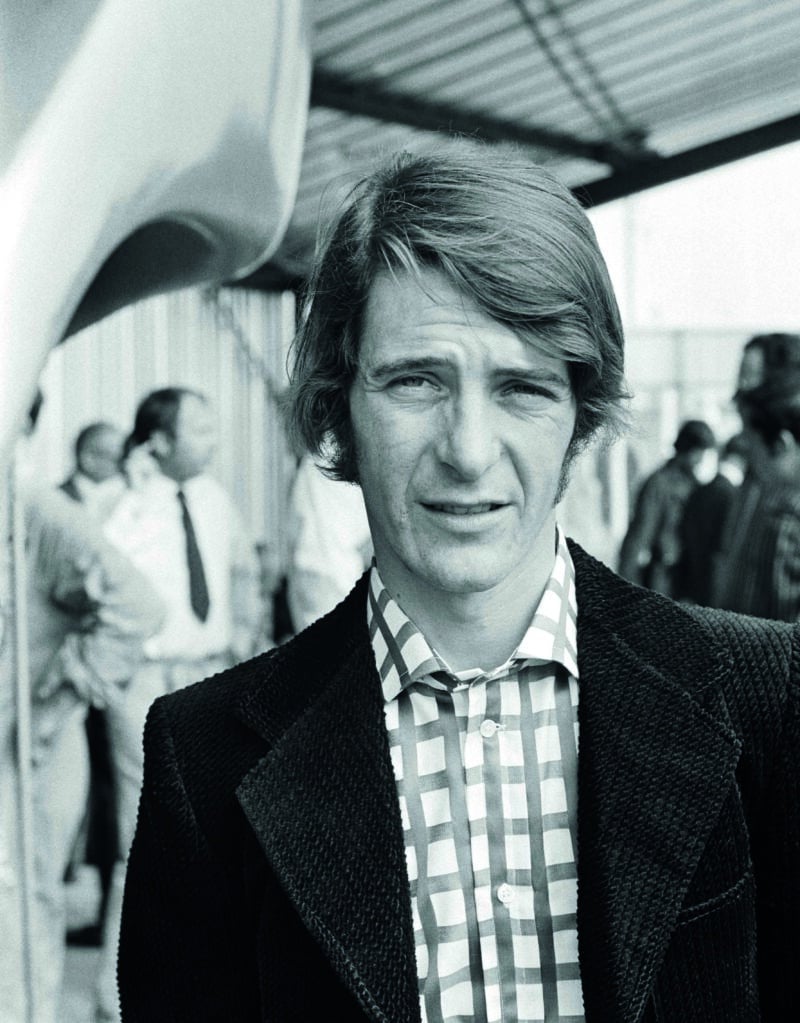

A rare outing without the hat

The Nordschleife, however, showed him in a very different light at the German Grand Prix in 1976. He was following Niki Lauda when the Austrian crashed heavily at Bergwerk and the car burst into flames. Brett Lunger could not avoid hitting the Ferrari and Guy Edwards stopped nearby. Both jumped out of their cars to help Niki, but it was Merzario who plunged into the fire.