McLaren's Zak Brown has the car collection of your wildest dreams

The car collection of McLaren Racing CEO Zak Brown is absolutely jaw-dropping, but as Damien Smith discovers, it’s kept in the same base as one of Britain’s fastest-rising race teams

Jayson Fong

To the left sits Jody Scheckter’s history-making Wolf WR1 and an Alan Jones Williams FW07. Further down the line there’s a trio of McLarens, once driven by a clutch of Formula 1’s biggest beasts: Ayrton Senna, Mika Häkkinen, Lewis Hamilton. Crikey. To the right sits a 1980s Indycar: wow, it’s Mario Andretti’s 1987 Lola, the one in which he should have won his second Indy 500. Next to it is Emerson Fittipaldi’s Penske PC18, the one in which he did win Indy. Then there’s Dan Gurney’s Can-Am McLaren M8D, a gorgeous Martini Lancia LC2 Group C and a Castrol IMSA Jaguar. We don’t know which way to look next.

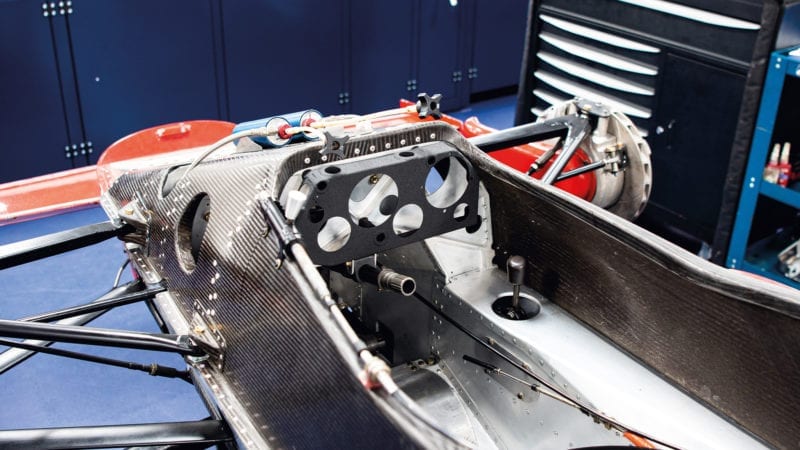

Try the following row of race bays. A Lotus 79 stripped to its perfectly formed bare monocoque; then a Bobby Rahal Truesports March 84C, the one Adrian Newey designed, that looks more than a little tired. It’s a new project, apparently. And what’s that little old-fashioned go-kart? Ah, it’s Senna’s, the one in which he returned to karts to try and win the 1981 world championship in Parma. Of course it is.

Upstairs on the mezzanine there’s much more: single-seaters, saloons from around the world, obscurities and oddities. At some point we really should close our mouths. Zak Brown doesn’t exactly keep his collection a secret, but to see them all under one roof, displayed and maintained in the manner each deserves… this is one chunky slice of nirvana for anyone who, like Brown, grew up falling in love with motor sport through the 1970s and into the ’90s. It’s almost as if he owns one of every racing car he ever had as a poster on his wall.

And what’s that little old-fashioned go-kart? Ah it’s Senna’s

But this pristine palace for horsepower is not simply a home for memories. Back on the ground floor, beyond the bays of historic wonders, mechanics are hard at work stripping the LMP2s and LMP3s that are just back from European Le Mans Series glory at Paul Ricard. And there’s the LMP2 Oreca, primed for transit, for what will be a monumental visit to the Le Mans 24 Hours. This is United Autosports, now officially one of Britain’s best and – on present form – most successful contemporary racing teams.

Jody Scheckter’s Wolf WR1 from the 1977 F1 season

BMW CSL with 2006 Ferrari F430 Challenge, a lightweight version of the road car, which Zak Brown raced in the US

Set of DTM tyres (D minus for spelling)

Ayrton Senna’s 1981 DAP kart

Modern LMP cars stripped for rebuild

A famous name peeks from the parts shelf

Maserati 250F, although this is not one of Brown’s

3.4-litre 24-valve V6 engine of the Cologne Ford Capri RS3100

IMSA Jaguar XJR-10

Newey’s 1984 March 84C, a work in progress

Modern LMPs among the classics

Lotus 79 ‘clothes’

Bastos Ford Capri

Don’t forget at Turn 1

United Autosports drivers’ wardrobe

Co-founder Richard Dean isn’t the sort to crow and make a fuss. He’s from Yorkshire. But there’s an unmistakable glow of quiet pride as he plays tour guide, and so there should be. Ten years ago, this dyed-in-the-wool racer and his old mate from California decided to buy an Audi R8 GT3 and a truck, leased a single unit and had some fun. Now United has become this, a multi-faceted racing emporium based in a new 62,000sq ft facility near Wakefield, just off the M62. Within these walls, there’s an unmistakable sense of adventure and all too obvious ambition.

“What I should be saying is we’ve got it all mapped out, a five- and 10-year business plan,” says Dean, son of Can-Am racer Tony, avid Leeds United fan and at 54, little changed from the gritty young bloke who battled his way through the ranks 30-odd years ago. “But the truth is, from that original unit, one truck and three mechanics to where we are today, none of it was planned. It’s just grown. Now there is more of a plan. As I’m understanding business, I see you’ve got to have one, even if it changes. To sum it up, it’s to ensure the company is not as reliant on our race team and its success. We’re going through a period now I couldn’t imagine, but it doesn’t last forever. You can find yourself in the wrong place, with the wrong car, wrong drivers or with a lack of sponsorship. I don’t want the business to be as up and down as life can be on a race team. You only need a promoter or a series to succeed or fail and your success goes with it, in either direction.”

Once lockdown ended in the summer and racing reignited, United Autosports banked a remarkable unbeaten run in the Michelin Le Mans Cup, the ELMS in both LMP2 and LMP3 and most notably in the World Endurance Championship. The LMP2 Le Mans class win delivered by Paul di Resta, Filipe Albuquerque and promising young Brit Phil Hanson just a couple of weeks after our visit marked the trio’s fourth consecutive victory at this rarefied level and also clinched United’s first world championship. Brown hasn’t yet tasted a victory in his ‘day job’ as CEO of McLaren’s Formula 1 team, but he sure savoured this one. On the back of it all, you can’t help wondering what might come next.

“I’m not sure I’ve got the energy to be any more ambitious than what we’ve already got on our plate,” smiles Dean. “But what will happen is Zak and I will sit down over a glass of red wine and I’ll come out with a new project and idea to work on.” They must get through a few bottles, given how much they’ve already committed to for 2021.

The headline is a collaboration with Michael Andretti’s Formula E team that will make United one of eight founding entrants – along with Lewis Hamilton and Nico Robserg – in the new Extreme E electric SUV off-road initiative. The five-event series, which places environmental action and awareness at the top of its agenda, kicks off in January. The Andretti United team will run out of the former’s Banbury Formula E base. “The tag line is ‘Race without a trace’,” says Dean, who was convinced of the concept while sitting next to founder Alejandro Agag at an awards ceremony. “The racing is a small part of the programme. The documentary series they will make on the places we are going, and why from an environmental point of view, is key. They have this legacy programme; if they go to the Amazon it’s to a part of the rainforest that has already been cut down, and when they leave they plant 200 hectares of new rainforest.”

The team has also acquired another base at Silverstone that was formerly the home of disbanded sports car team Strakka Racing, and will run a pair of McLaren 570S GT4s in the category’s European series, marking a return to the form of racing in which United began. The McLaren link is no surprise – and it would hardly be a shock if one day soon it’s United that takes the 1995 Le Mans winner back to La Sarthe in the new Hypercar/LMDh era. Dean isn’t shy about acknowledging how the new categories open up possibilities to bid for an overall Le Mans victory, even if he’s careful to stop short of name-checking McLaren.

“Currently there is nothing above LMP2 in my mind,” he says. “Toyota might disagree, but we can’t go and compete with them in LMP1. But that top class is about to get shaken up and hopefully that means teams like ours can have a realistic opportunity. That is the ultimate ambition, to end up in the LMDh class for the world championship and perhaps even an IMSA programme.”

The smart, new facility would surely impress any manufacturer eyeing a partner for a Le Mans bid, especially one that has born such success in LMP2, the category upon which the LMDh cars will be based. It all makes sense for United. “There are a lot of good race teams that we have aspired to match,” says Dean, who credits the new factory as the key to his team’s recent run of success – even if moving in just as a global pandemic broke gave him a few unforeseen nightmares. “But we don’t want to be just another race team. Without being too cocky, we want to be a little more and to do it you need a facility like this. If we want to attract a manufacturer who wants to go into LMDh, you’ve got to have a facility and personnel to match that ambition.”

Brown loves his Indycars. This is Michael Andretti’s 1991 title-winning Newman-Haas Lola, opposite his 1981 Porsche 935 JLP-3

On the people side, United boasts nearly 40 full-time employees, including some well-established names. Former Jordan F1 lynchpin Trevor Foster runs the LMP2 side, while Dave Greenwood – Kimi Räikkönen’s race engineer at Ferrari – is technical director. In the historic restoration and maintenance department, Paul Haigh – aka ‘Flower’ and a long-time friend of Dean’s who engineered his F3 car way back in 1989 – remains the guardian, but will now be joined by Williams veteran Dickie Stanford, who has left his role managing the F1 heritage collection following the company’s recent sale to Dorilton Capital. Stanford’s hiring is a sign that United has aspirations beyond maintaining Brown’s cars, as other owners are drawn to the company. The Maserati 250F sitting between the M8D and LC2, for example, isn’t one of Brown’s (it’s the wrong era, for a start). There’s also evidence of road car restoration, including a newly minted Jaguar E-type, another avenue that appeals to Dean’s desire to build a sustainable business away from the boom and bust uncertainty of running a racing team.

Classic car restoration is a new avenue to pursue

But how is this expansion funded? There’s a perception that lingers, despite all the recent success, that United is Brown’s plaything. Dean bristles at the suggestion. “Everybody thinks Zak funds this,” he says. “We fund it ourselves through our business activities. Each race team has to have at least as much money coming in as going out.

“There is a perception and it’s a bit irritating. Zak contributes here for the work he has done. If he wants to race he pays like every other customer. We look after his entire collection of race cars and that takes up a lot of space, and we charge him an overhead contribution for that. The race team has to stand on its own feet; LMP2, LMP3, WEC, ELMS – if it doesn’t make business sense we can’t do it. Zak is a shrewd businessman who loves racing, but he doesn’t let his obsession of racing get in the way of the business.

“Having said that, I’m lucky that I’ve got someone who is smart in terms of business and is also passionate about it. When we set up, he provided the company with resources, but as a loan. We paid back that loan a long time ago. We own the business 50 per cent each and he leaves me to run it, but he surprises me how much he wants to be involved. We speak every day. He texts me through races and we speak directly after. He comes up here at least once a month, but what he wants to know is the big picture, not detail. I’m also lucky that he’s the ultimate networker, and his little black book of connections is probably the biggest in the world. In terms of access, introductions and opportunities we’re in a good position. That’s probably the biggest investment he puts into the business: time.”

Two worlds under one roof with classic car projects….

…alongside preparation of cutting-edge Le Mans Prototypes

What’s heartening is that this apparent growth ‘by mistake’ has been achieved by two racers who also happen to be genuine friends. “It’s cool to achieve this with my best mate,” says Dean. “He’s so proud of what we do, and so involved from the business side. Ultimately at McLaren he’s an employee but he owns half of this. That’s not lost on him. Winning is everything, isn’t it? When we won both classes at Paul Ricard this summer, I don’t think I’ve seen him as happy. It was great to share a beer afterwards and say, ‘How did we do this?’” Brown and Dean can probably look forward to a few more celebratory beers in the future. At United’s success rate, perhaps they should open a brewery…