Birkin's Lotus Seven replica: Chapman would approve

Together with the Meyers Manx beach buggy, Colin Chapman’s Lotus Seven must rank among the most imitated of all kit car designs. The best-known Seven replicas (in Europe, at least)…

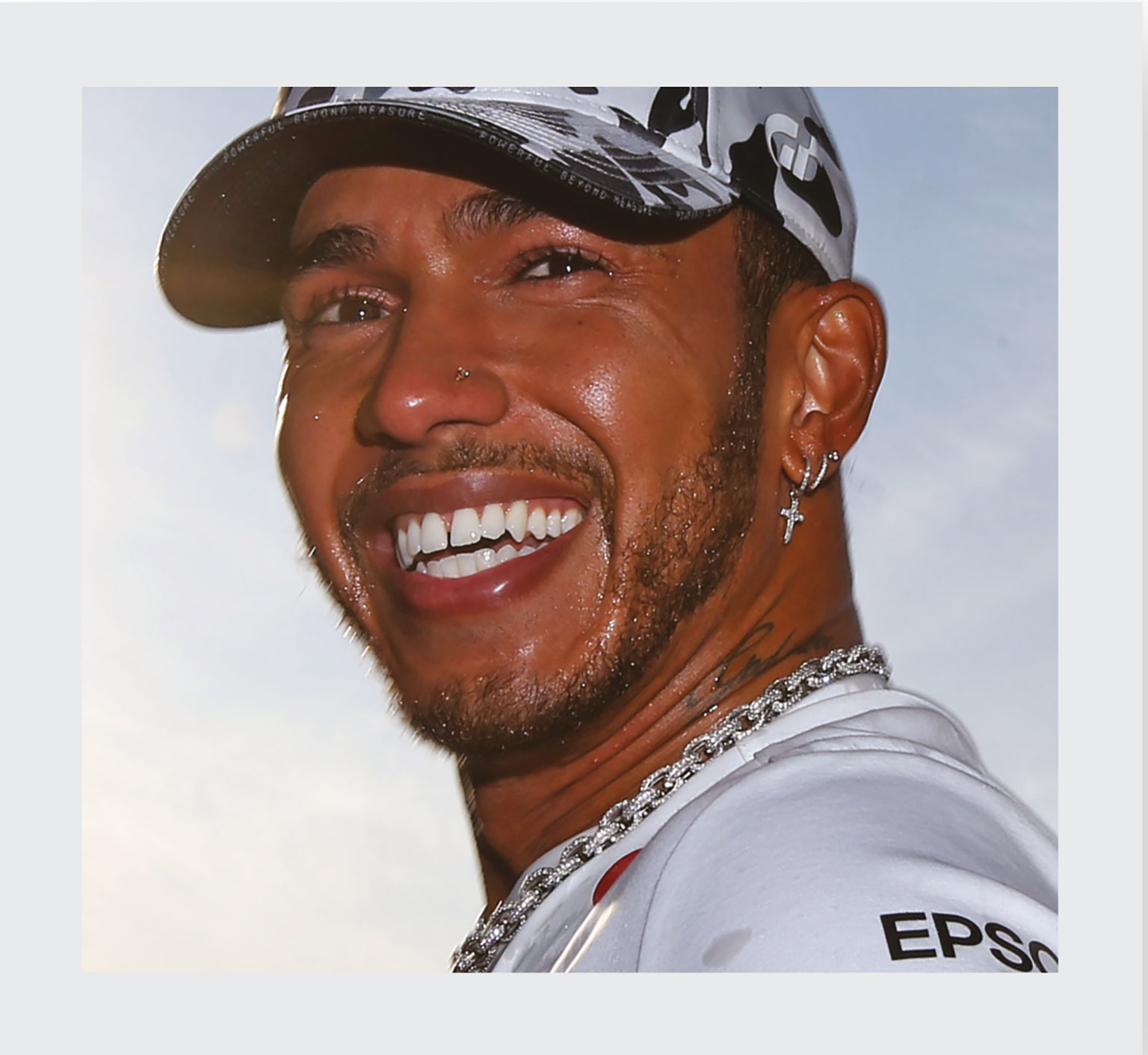

Much has been made of Lewis Hamilton’s sixth F1 Drivers’ World Championship, and of where this may place him in the list of all-time greats.

But upon what parameters have people based their judgements? Even though motor sport is relatively young – around 125 years – ‘all time’ is one helluva long time – and modern racing is a hugely different activity now from what it was. Race driving today is so altered – and is now shared not just with often-limiting technology (the car) but also with the back-up blanket of radio and telemetry-linked engineers (and commercially-minded managers) – that comparison between historic eras is really impossible.

Unlike other sports, motor racing has not been played on any pitch, nor regulation running track. Instead it’s a technological sport, pursued over a variety of courses, by a variety of people, confronting different challenges, using hugely different equipment.

How can one truly compare an era of cork helmets, polo shirts and bulging midriffs with a current climate of Halo head protection systems, Tilke-designed tracks and racing-dog athleticism?

Stats are no help either. Every stat demands qualification, since the number of events and the rules governing them have changed so markedly. Where a World Championship-qualifying Grand Prix was once a relatively rare event, highly valued – as in the truncated 1955 season when only six road-race GPs qualified (discounting the FIA’s potty political ploy of having included the Indy 500 in the first place) – there are today 21 each year, so arguably the currency has been devalued.

What, then, might be a worthwhile measure by which to compare great racing drivers from different periods? I was brought up to regard fellow driver’s true assessments – not the ones they necessarily admit to, but the ones they hold instinctively – as being the true identifier of an era’s standard setter. These standard setters of each era are the stars whose lap times all rivals have instinctively studied first. Stirling Moss once likened the value scale to a pyramid: “On the point up top there’s only room for one, then below him there’s room for maybe three or four, and below them… there’s the rest.” And by that measure Lewis Hamilton is most decidedly right up there amongst the greats.

Some 73 years have passed since the resumption of significant motor racing after World War II. Since then, I would identify only 13 drivers who have been the true standard setters. The first of those didn’t even live long enough to see an F1 Drivers’ World Championship race – and each must be considered in combination with the cars he drove, for one can argue that signing the right team contract has proven to be the only constant on the road to greatness.

This is a tough judgement on great drivers, as not all could top Stirling’s pyramid…

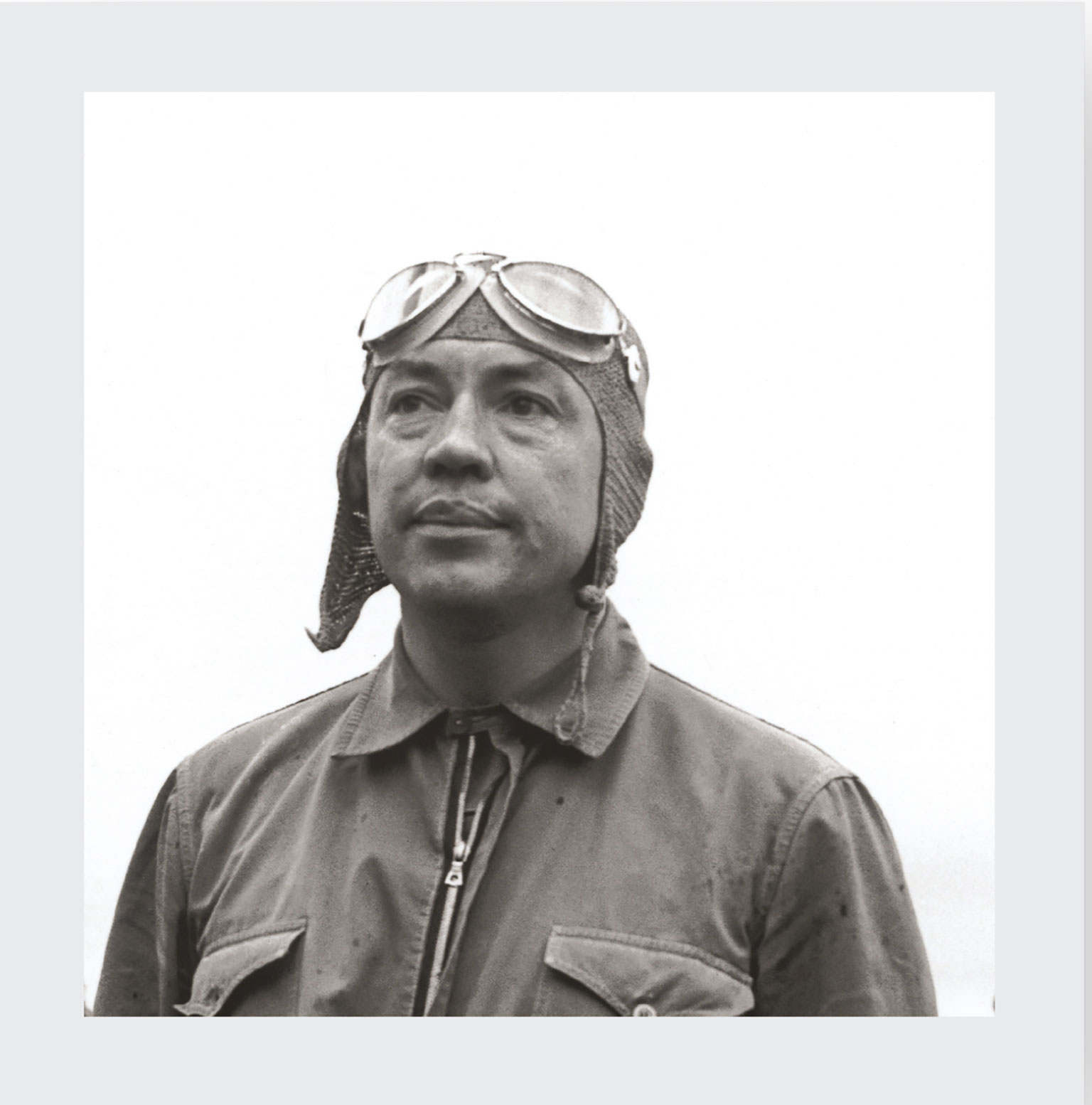

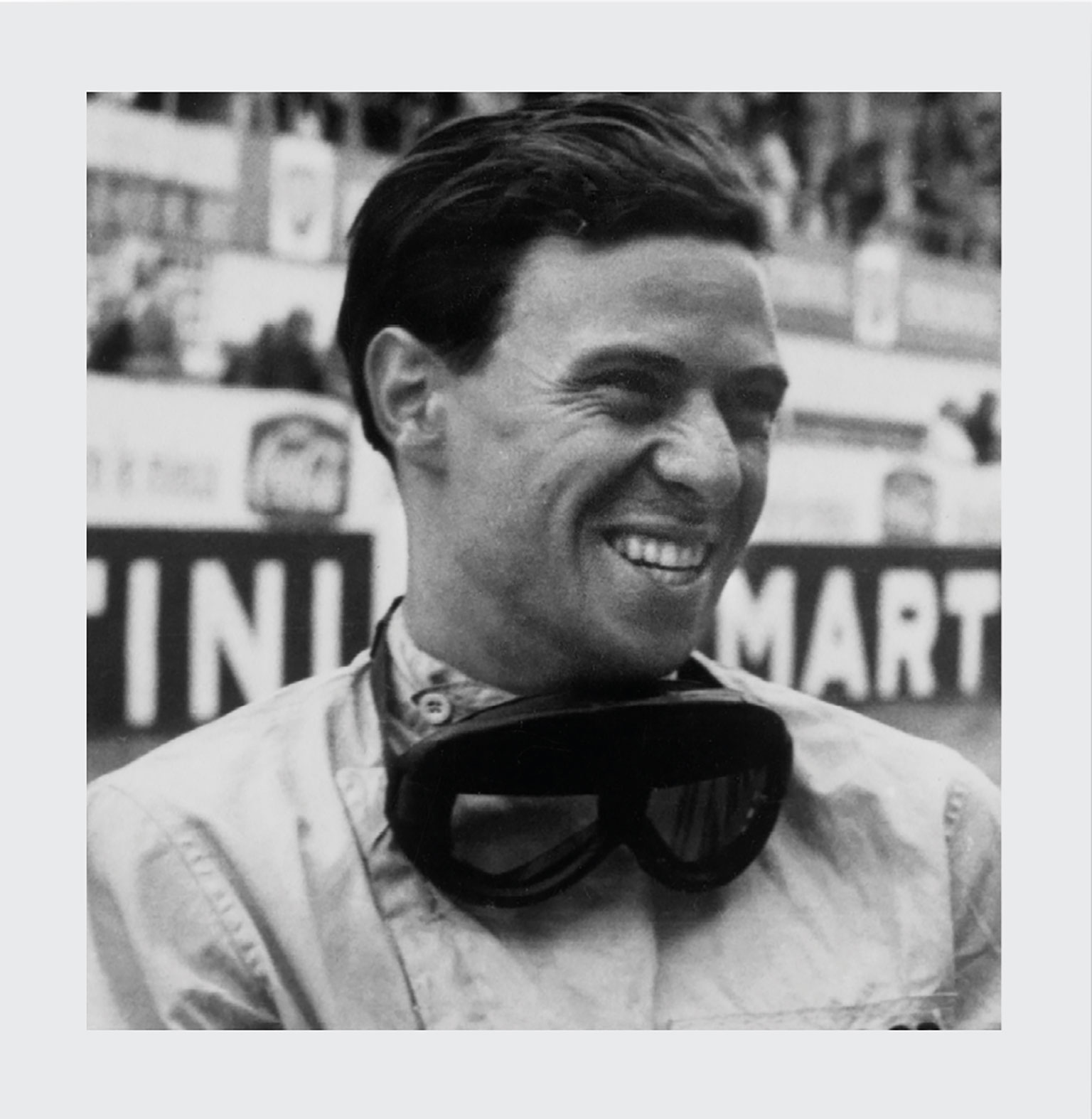

Widely regarded as the standard-setting Grand Prix driver of the late-1940s, Wimille was – like Jacky Ickx – the son of an enthusiastic motoring writer. He had begun racing aged 22 in 1930, began winning at significant level in 1932, won Le Mans twice and led Bugatti’s team with distinction pre-war. Once peace returned he shone for Alfa Romeo, won 10 major races – larking about with a little Gordini for fun –and as the standard-setting veteran he had become he willingly shared advice and experience with newcomers he rated. Tragically, he ran out of luck – not skill – while practising in a Gordini at Palermo Park, Buenos Aires, Argentina on January 28, 1949 – dead at 40.

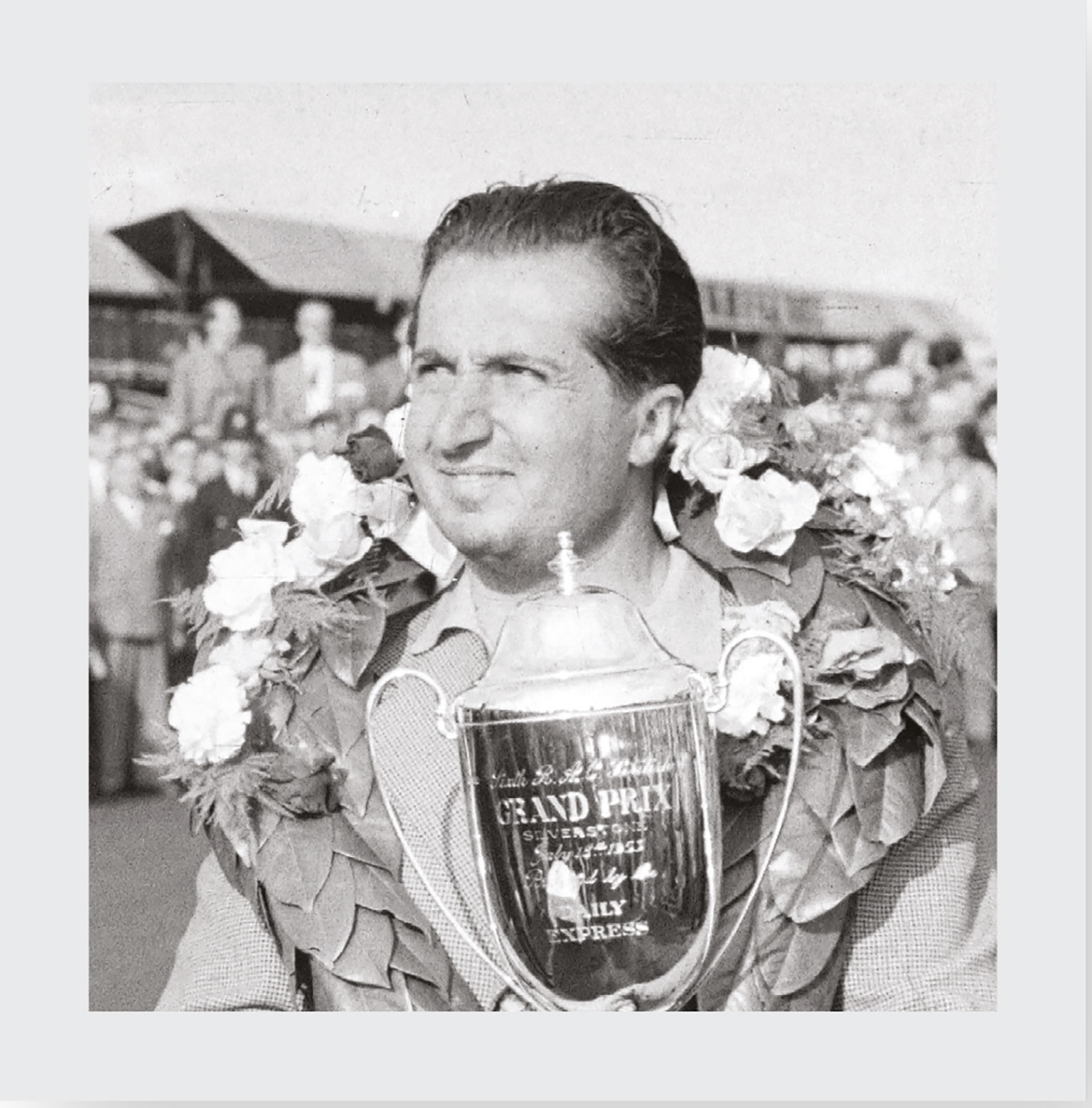

The son of a famous racer – Antonio Ascari, Grand Prix winner 1924-25 for Alfa Romeo – ‘Ciccio’ (more or less ‘Tubby’) Ascari raced motorbikes before cars just pre-war, then emerged post-war with Maserati before being poached by Ferrari – with which he won some 44 significant races between 1949-53 to becoming the sport’s first double World Champion, 1952-53. A rift with Mr Ferrari over money made Ascari move to Lancia in 1954-55, and he won the mighty Mille Miglia sports car classic and two non-championship F1 GPs. When Mike Hawthorn joined Ferrari for 1953 ‘Ciccio’ offered to lead him round Spa during practice for the Belgian GP. Mike said at the time: “I stayed with him for a while, but once he decided he’d shown me enough The Old Boy just buggered off!..” That’s surely the true mark of a standard-setter. On May 26, 1955, four days after tumbling his Lancia D50 into Monte Carlo Harbour, Ascari crashed fatally in a sports Ferrari at Monza while exploring the after-effects of his ducking. He was just 36.

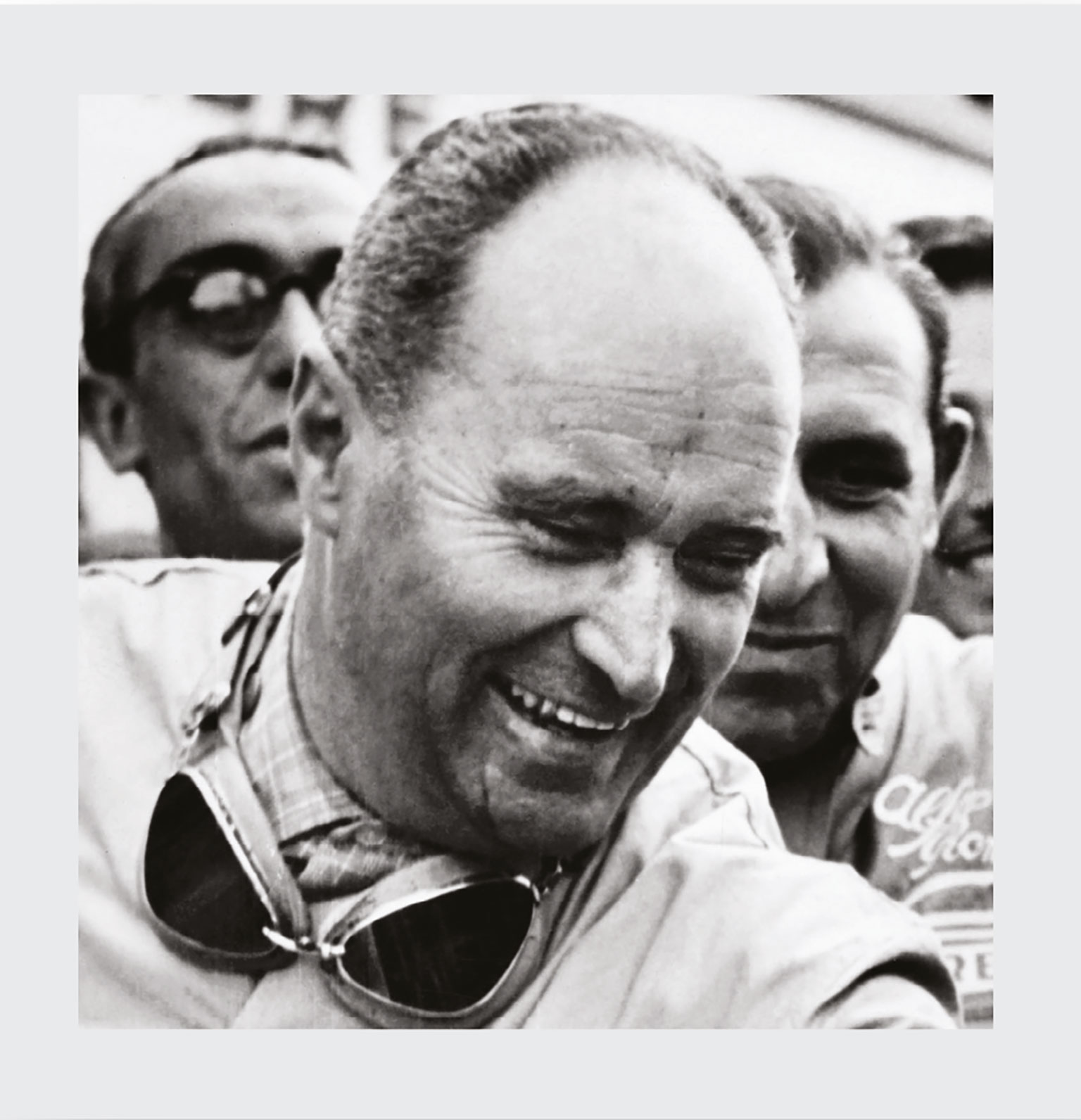

The rural Argentine mechanic who developed his driving skills – and stamina – in hyper-distance Carretera Turismo racing before aspiring to single-seaters, backed by the Perón regime’s national automobile club. Fangio was already 38 when he burst onto the European scene in 1949, driving a club-backed Maserati. Alfa Romeo snapped-up his services for 1950, he won the first of his five world titles in 1951, broke his neck in 1952, then returned to dominance 1954-57 with Maserati, Mercedes-Benz and Ferrari. Fangio’s sublime skills were evident in any kind of car, though he would recall: “It was my fortune to have luck in Grand Prix cars, and not in sports cars…”, in which category his protégé Moss first beat him. Fangio had the rare gift of maturity combined with a gracious nature, occasionally generous to his rivals. One could sense that his true backbone was of absolute spring steel.

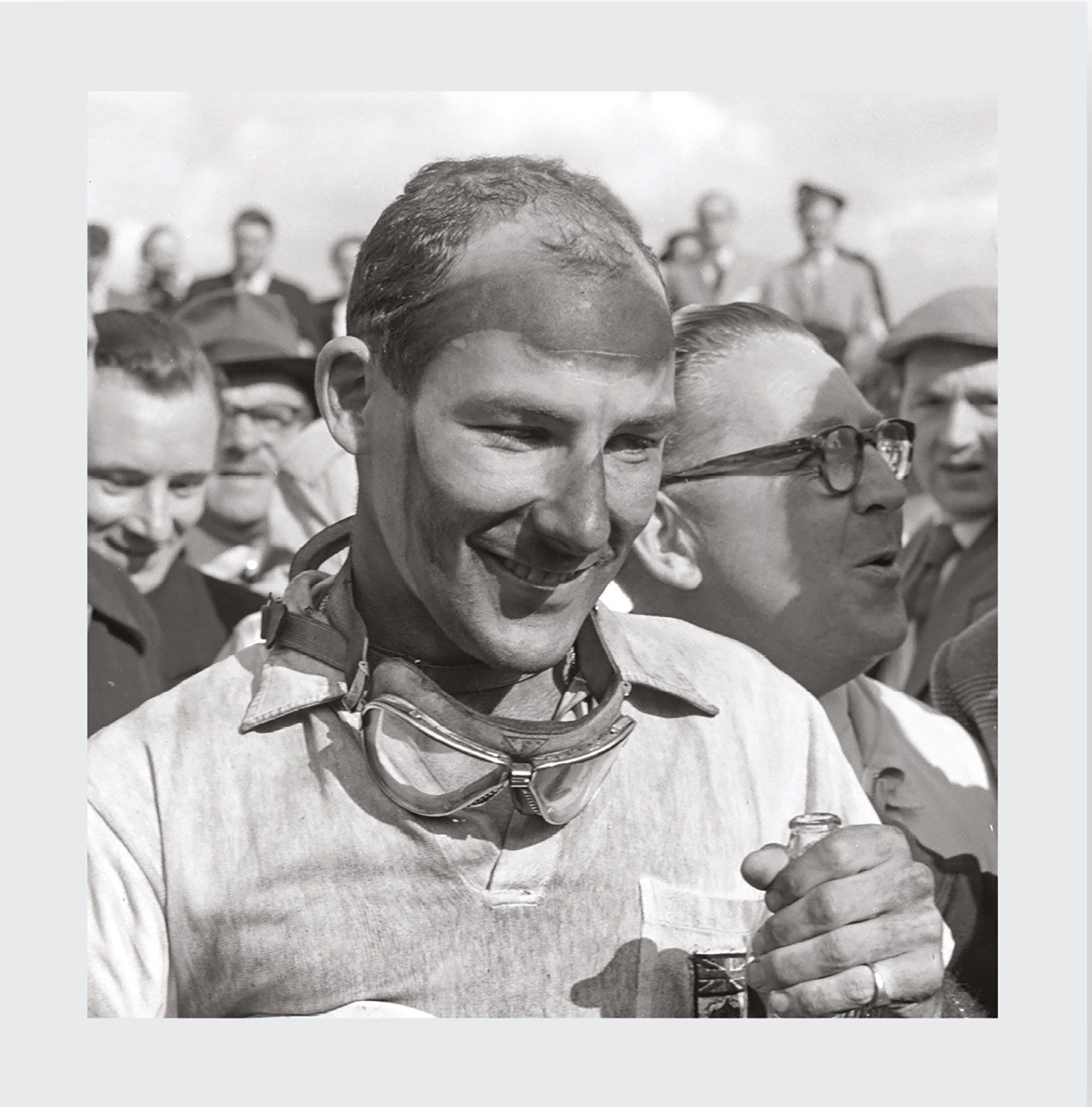

In period, absolutely Britain’s best – and perhaps the greatest living Englishman. Most leading 1950s-60s drivers maximised income – and glory – by driving everything available. Moss’s transcendent skills were shown in F1, F2, F3, sports, GT, saloon and even rally cars. After early years wasted seeking a competitive British car, he began winning in F1 with a Maserati 250F in 1954, earned a Mercedes-Benz drive for 1955 (winning the Mille Miglia) – and learned in Fangio’s wheel-tracks. He at last found a competitive British-built F1 car with Vanwall in 1957-58. Having helped achieve its first frontline GP win, followed by the first British victory in the F1 Constructors’ Championship, Moss was marooned by Vanwall’s withdrawal for 1959. Confident of his own ability and quite fancying the underdog role he then drove for private owner Rob Walker 1959-62 in Cooper and Lotus F1 cars – but the world title eluded him. Still, none of his peers had any doubt who they had to beat. He was only 32 by the time of his career-ending crash at Goodwood in 1962. In contrast to Fangio whose mantra was “The sensible driver wins at the lowest possible speed” – Stirl’s was “I love to get stuck in and have a real tear-up…” And amongst modern drivers Hamilton is perhaps his only heir.

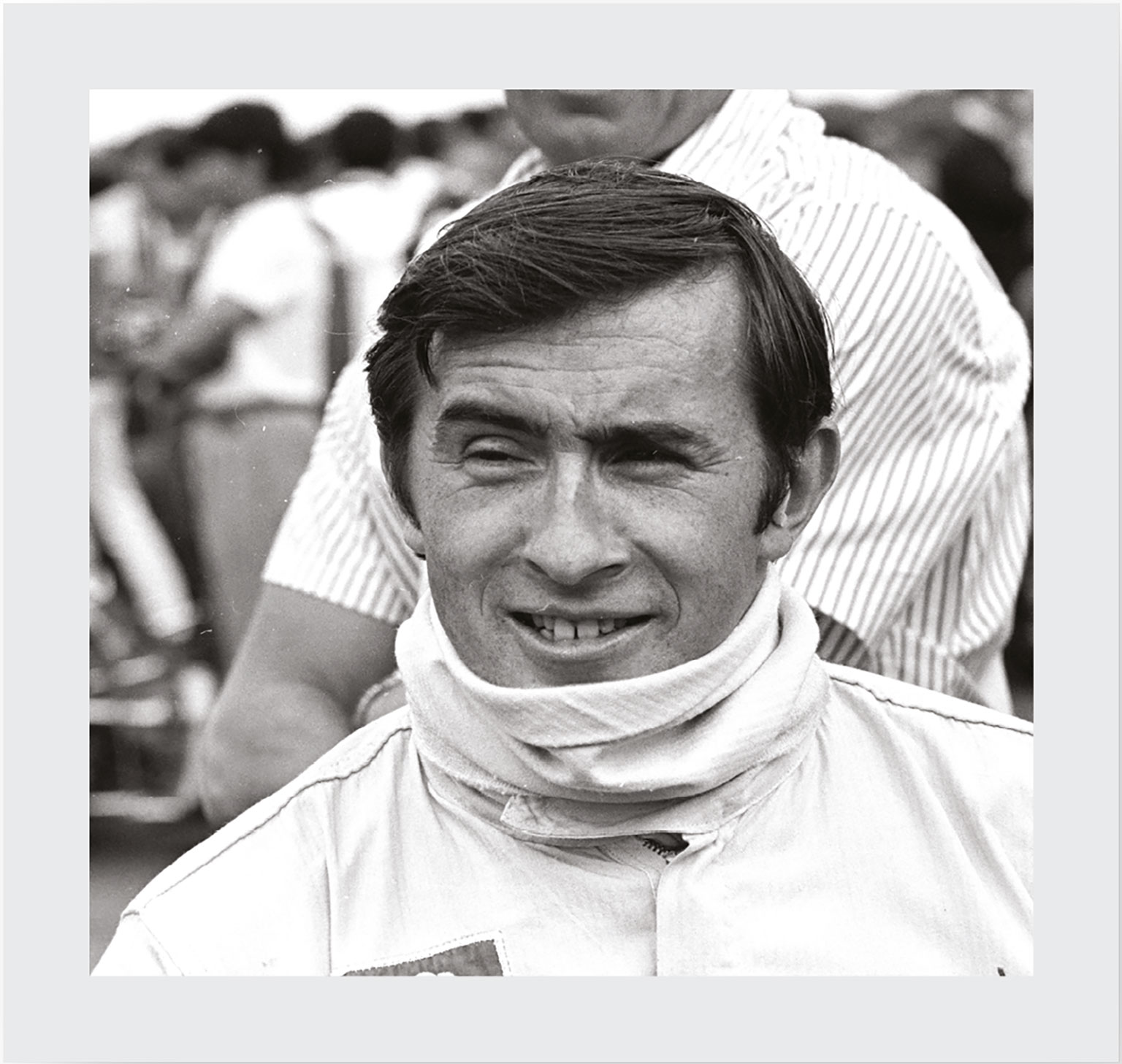

The charming, thoughtful sheep farmer spent his entire F1 career with Team Lotus, 1960-68. By 1961 Moss would describe him as “the only young driver I would fear,” and when he began winning races with the Lotus 25 in 1962 it was Clark who assumed Moss the Maestro’s mantle. Colin Chapman told me: “I don’t think Jimmy ever realised just how good he was,” and he certainly sustained a similar humility and respectful popularity to Fangio’s before him. Not least he was similarly encouraging and supportive of one who would replace him, fellow Scot Jackie Stewart. The hole in Jimmy’s record was that he rarely competed at topline sports car level – a rare shortfall for a race-driving genius. His life was cut short by tyre failure in an F2 Lotus 48 at Hockenheim on April 7, 1968. Like Moss, he was 32.

Cocky, bouncy, wee Jackie just seemed born for greatness – kid brother of established racer Jimmy Stewart. He showed stupendous class from his earliest races, and in 1964 made not only his F3 debut, but also his F2 and F1 debuts and ‘straight out of the box’ proved almost fully-fledged. He won his first frontline GP in his learning season with BRM in 1965, before his progress was punctuated by the Belgian GP accident of ’66. By 1968 with Ken Tyrrell’s Matra team he had emerged as the real deal, and three World Championship titles, huge commercial success and the life of a team principal and entrepreneur ensued, after his retirement at the end of 1973 – aged 34.

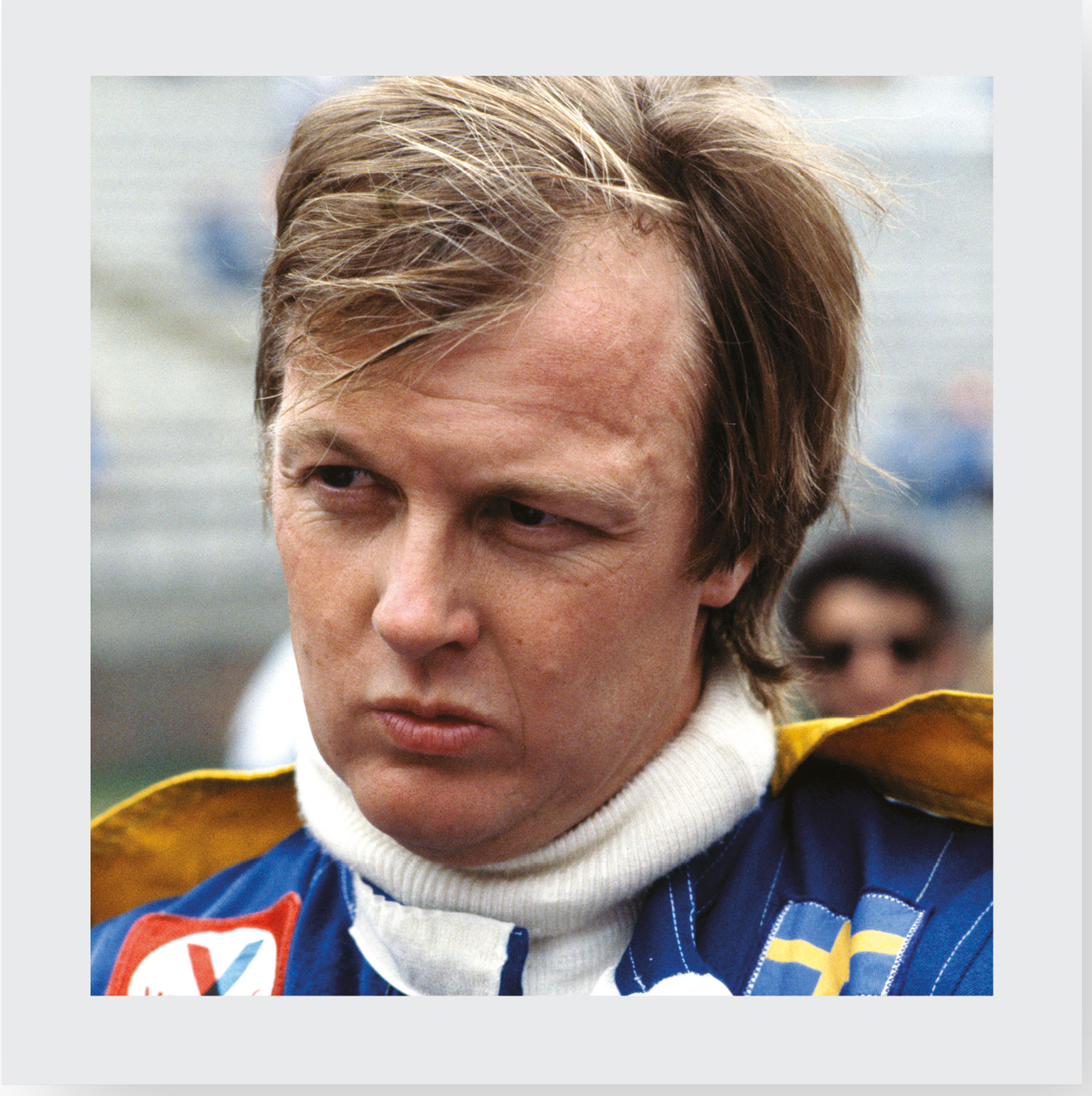

Never a World Champion but could anyone claim that Ronnie was not the standard-setting F1 driver of his heyday, with John Player Team Lotus? Ronnie’s career path was similar to – if rather slower – than Jackie Stewart’s – but before his F1 debut in a private March in 1970 his F3 and F2 exploits had left none in doubt that here was a special talent. Quiet, modest and friendly, the tropical fish-keeping ‘SuperSwede’ simply grew horns and a tail on track – and was spectacular and quick if his car permitted. Subsequent success of the driver below somewhat submerged Ronnie’s status in 1975-78 but what a driver he was. He was 34 when he was killed in the 1978 Italian GP, on September 11, 1978.

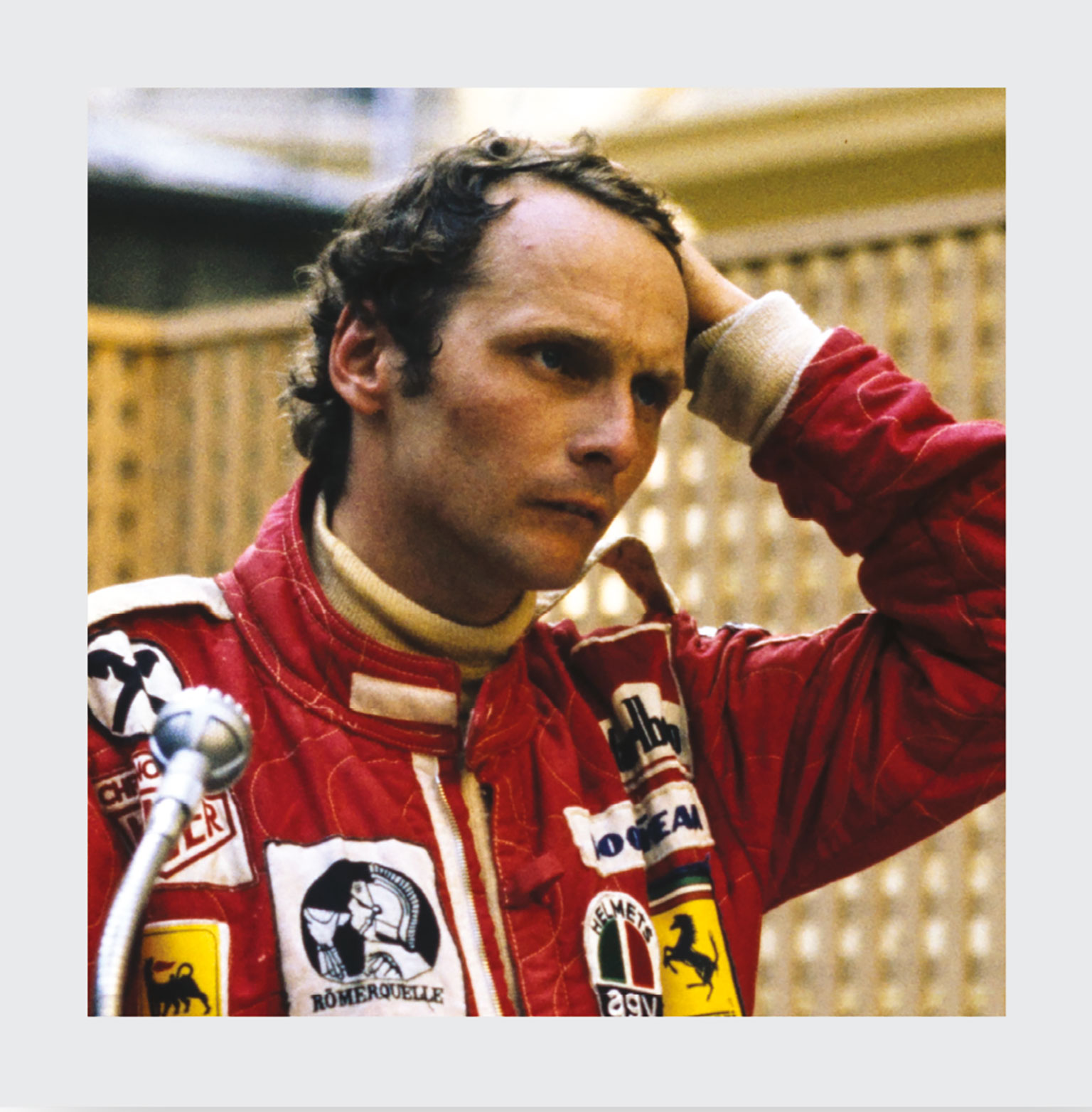

One of the most dedicated, motivated, bright and uncompromisingly manipulative racers. He won three world titles after gambling every penny on his career. After buying a March drive in 1971 he won a BRM F1 drive for 1973 and announced himself to the team mechanics by declaring “You all think that I am just a vanker – but vun day I vill be Vorld Champion!” And he was. He was perhaps the first modern F1 standard-setter in exclusively driving those cars to the exclusion of other categories. Finding his feet with Ferrari through 1974 he won races but was yet to show maturity. That came in 1975 – and the story of ’76, his German GP crash and burns, is just too familiar, and heroic. He bounced back to another title in 1977, later came back after brief retirement 1980-81 to win again with McLaren. He passed away in 2019, aged 70.

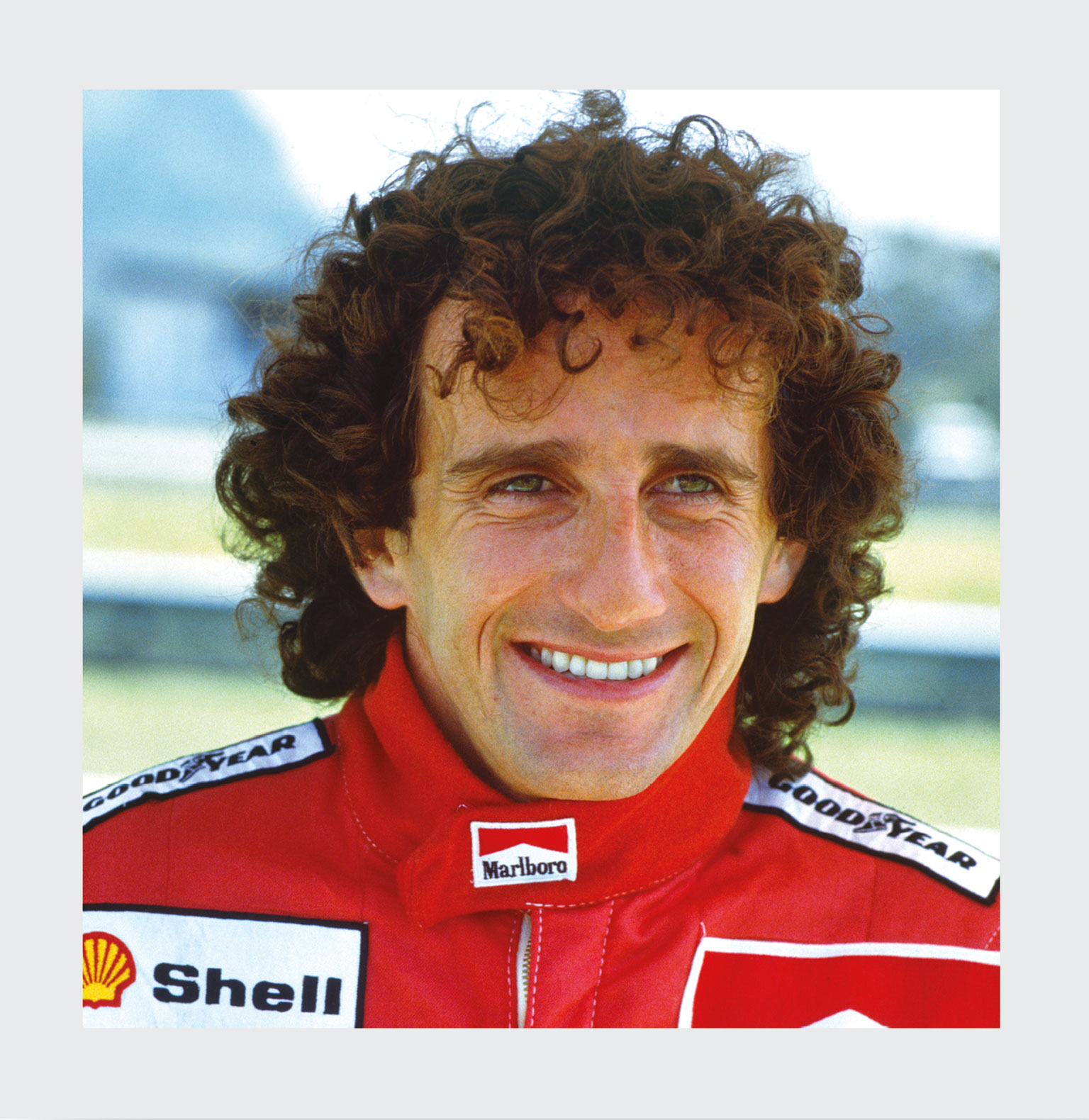

The Professor’s metronomic driving style might have made winning look boring but in the neat, near-flawless tradition of Clark and Stewart, Prost was truly special – as his four world titles attest. John Barnard of McLaren described how: “Lauda had been stroking it with us, content that he could beat his team-mate whenever he needed to. But then Alain arrived – and Niki found he had Concorde up his backside…” Gallic flair combined with coolness and calculating control.

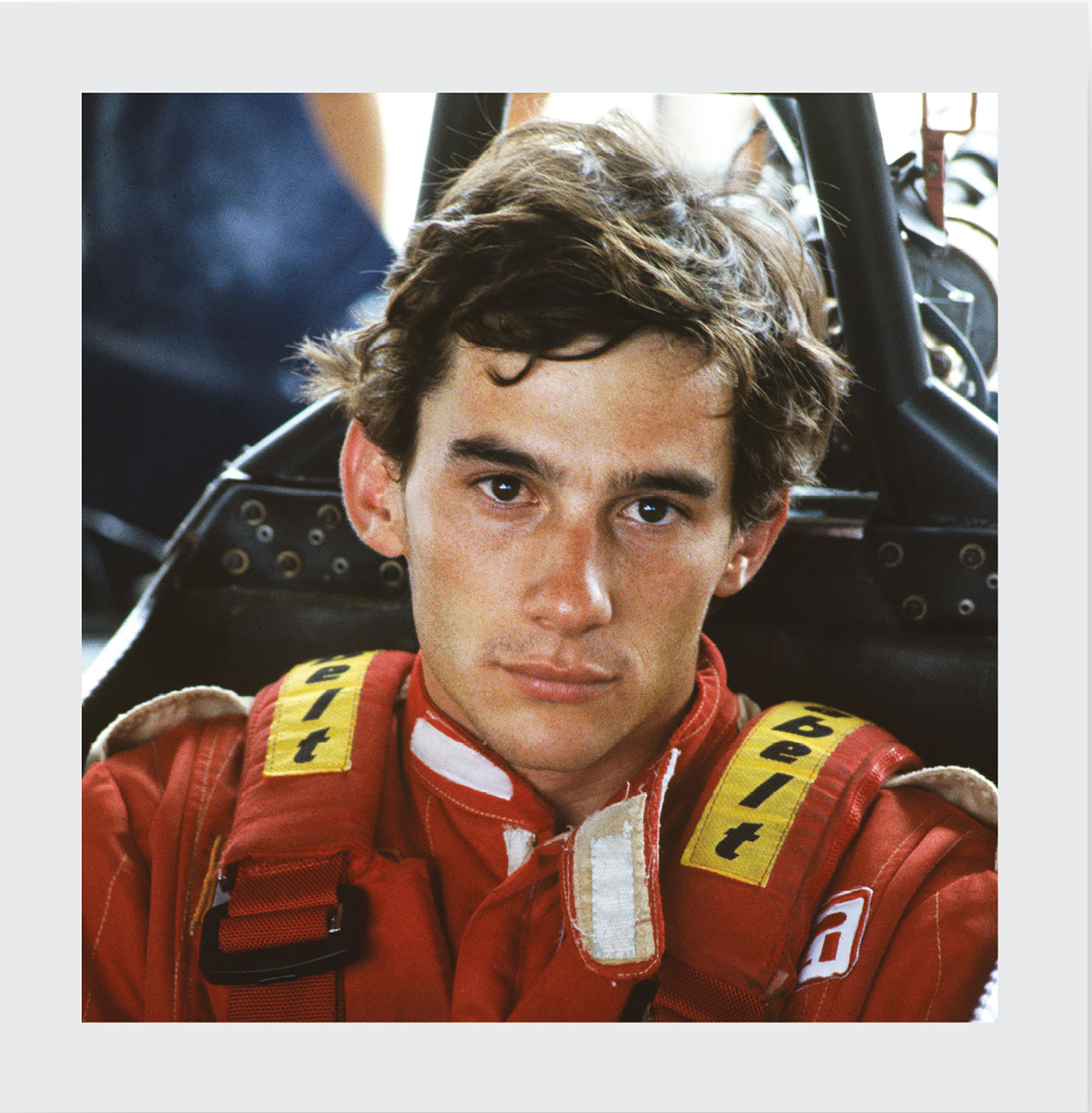

A split personality – the brilliant and driven Brazilian came to define selfish obsession and previously seldom-seen determination to win or bust, at anyone and everyone’s expense. He and Prost were destructively alike, and caging them within the same team turned it into a pressure cooker. Senna was perhaps the first of the modern-era drivers who could bury the diminishing dangers confronting his profession and go for bust regardless. It is doubly ironic then that the three-time World Champion should have crashed fatally at Imola on May 1, 1994… again aged 34.

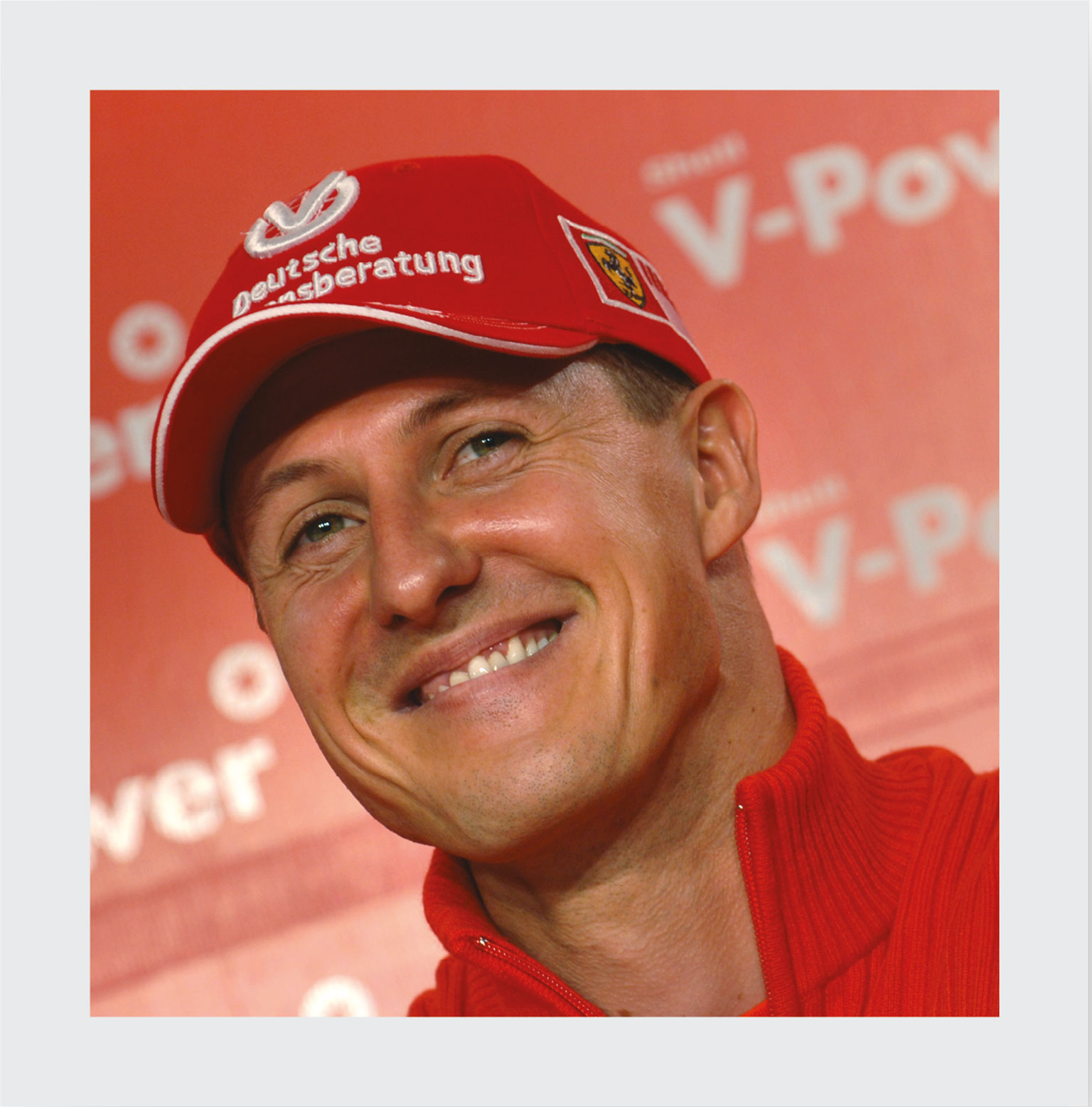

The glittering example of the modern-era driver with transcendent talents, ring-fenced, promoted, and his career prolonged by safer circumstances, some fine cars and a well-organised and capable team. The immensely motivated German shared many of the most admirable characteristics of Prost and Senna – combined with what in his period proved consistently to be the quickest tactical mind. From a Daimler-Benz nursery of endurance sports car racing, Michael progressed through his twin Benetton F1 world titles in 1994-95, to those further five in succession 2000-2004 with Ferrari. His team’s commitment to his title interests at the expense of his team-mates jarred for many – but what a racer, indeed…

The four-time World Champion certainly became as adept at brandishing his index finger after winning as he was behind the wheel of his Red Bulls through his successive Championship-winning seasons of 2010-2013. Despite demonstrating the modern-era selfishness of the great racing driver, he is an engaging, interesting personality – a 34-year-old superstar with a rare appreciation of those, and that, which has gone before.

Tutored, trained and promoted by his father Anthony, the kid from Stevenage has grown almost literally as a lifelong racer, and is very much in the Moss mould – never happier than in a battle on track. While the likes (especially) of Hamilton’s hero Senna and Schumacher overstepped the limits of condonable on-track behaviour in their obsessive quest for personal achievement, the 34-year-old’s six world titles have been accumulated through tough, uncompromising, but almost entirely sporting drives on track. Less engaging is the occasionally childish post-race reaction to defeat, but even this great standard-setter is not alone in that. And, let’s face it, many of the greats that have gone before will look down, and they would understand…