The Unknown Warrior

John Bintcliffe was Audi's surprise choice to partner Frank Biela in the BTCC. Here's why You've no money. You have no karting experience or family background in motorsport to call…

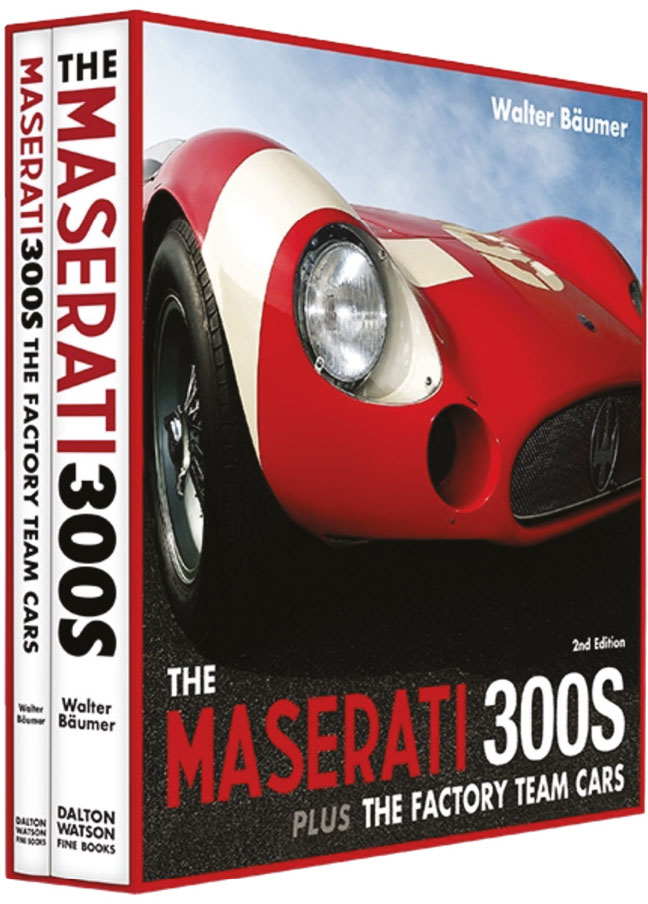

Walter Bäumer

Published by Dalton Watson, £195

ISBN 979-1-85443-29-7-1

Yes, this is a second edition, which we don’t often review. But since its 2009 appearance this detailed repository of Maserati facts and figures has been augmented, corrected with new knowledge and illuminated with an astonishing 400 mostly new photographs. The result is another of the new generation of massive works which are boosting B&Q’s sales of shelf reinforcements no end. And as few of the fine pictures in the original are carried over, there’s a good argument for retaining both.

Though best-known as a photographer, Bäumer comes from racing stock: his uncle, also Walter, was a Mercedes grand prix test driver pre-war, turning out for them at Donington in 1938 and then winning the 1940 ‘Mille Miglia’ for BMW – thanks to Walter Jr we featured his fascinating scrapbook from that event in our August 2001 issue. And in 2002 Walter organised for our then editor Paul Fearnley to drive Fangio’s lap-record 250F on the Nürburgring. That’s influence.

Today the author devotes himself to researching the marque and it’s this devotion which has uncovered so much fresh material for his Mk2 book. Yet as a full-time historian Bäumer’s frustration over historical dead-ends is obvious – for instance the missing records of Maserati’s US operation which, he says, might solve “many of the mysteries that puzzle researchers today”. With crash repairs, swapped chassis numbers and fudged paperwork I doubt if there’s any cadre of significant cars where the entire story is recorded and accepted. Somewhere there is always an “ah, but…” hovering in the wings, particularly as the cars are now priced above rubies. In fact this edition carries a publisher disclaimer saying it is “for entertainment only and… not for valuation purposes”. Yet it’s a fair bet that somewhere, someone is grinding their teeth.

Still, for the unspecialised among us, expertise such as this gives us the current picture of a subject. And until Bäumer traces those US papers this production will answer any question on these sleek and pretty cars which were so successful in mid-Fifties sports car racing. Some say the 300S, with its de Dion transaxle, handled better than its Ferrari rivals – and by ‘some’ let’s quote Mr S Moss, who won two 1000km races in one and commented that a good 300S “had a chassis that was infinitely superior to any front-engined Ferrari”.

Surprisingly Bäumer doesn’t spend too much time on the technical aspect and the 250F genes it shared – it’s all over in 25 pages of the 564-page total. Then, rather than haul us through annual diaries Bäumer breaks up his story in several ways: the smaller volume is purely photos of the four works cars, the larger covering the life histories of all 26, including the customer cars. It starts with sections on the World Championship, US racing, and South America, where so many European exotics declined into neglect (Bäumer mentions a 300S still competing in the 1970s), then sales and advertising, featuring the firm’s period brochures for its racing offerings. Thereafter Bäumer focuses on individual chassis, beginning in 1955 with the three commissioned by Briggs Cunningham, the model’s first customer. His order must have encouraged the factory: if enough cash began flowing from such wealthy privateers, they might be able to stand up to Ferrari, if not to Mercedes and its sophisticated 300SLR. But Ferrari had the cleverer business model: create and sell a bevy of beautiful GT cars as a priority to maintain the cash flow to the race department. The number of wealthy people who don’t race is far greater than those who do. It would take Maserati several years before it could offer a properly sorted and luxurious Grand Tourer, by which time works racing was over.

“Warned to look after the cars, which had all been sold, the race produced a scarlet scrapyard”

It was the disastrous 1957 Caracas Grand Prix in Venezuela which finished off the Maserati racing team for good. Although team director Nello Ugolini had warned the drivers beforehand to look after the cars as all were already sold to private buyers – funds needed desperately by the struggling firm – the race produced a scarlet scrapyard of four crumpled and charred Maseratis, the entire works team. And when Argentina’s Perón government defaulted on payment for some machine tools, the Modena racing operation finally stalled. Thereafter it was down to privateers, some with significant quiet assistance from the works, to bear the trident and the cars raced widely. Not only is every race listed, but so are drivers and most of the owners through the years.

(One thing not mentioned is which 300S, being delivered home after restoration, broke loose from its winch cable and ran back down a ramp into steel doors – cue immediate return trip to the repair shop. But I promised to keep quiet about that.)

There are plenty of arresting images: a crane heaving cars out of what looks like a livestock truck, a pipe-smoking marshal holding a cardboard clock with the time in a 12-hour race, a blazing wreck at Sebring. While most are big, crisp and bright – there’s even colour from 1955 – Dalton Watson isn’t afraid to run a grainy shot if it shows something interesting, boldly running one fuzzy image huge because it shows how close to death Jo Bonnier came when the lamp post he hit crashed down across his car seconds after he leapt out of it.

If Fifties sports-racers are your thing, this is a helping and a half to indulge in. Just make sure it goes back in the slip case afterwards – such books are collectible themselves.