Lunch with... Jean Alesi

He swiftly earned cult status with some feisty performances in his early Grands Prix, but fate decreed that he would score only one F1 victory

Charles Coats

By a strange quirk of history Jean Alesi’s CV includes just a single Grand Prix victory, achieved at Montréal in 1995. The charismatic Frenchman’s impact on the sport was so much greater than his record suggests, but year after year circumstances seemed to rob him of potential wins. And then there was the time he followed his heart and chose a future with Ferrari rather than Williams – and thus walked away from the car that would dominate F1 for the next few seasons.

At 52 Alesi remains fit and trim, but he insists that after a disappointing final fling at the 2012 Indianapolis 500, he is now retired from racing. Instead his focus has moved to guiding the career of 17-year-old son Giuliano, who competed in the 2016 GP3 Series and is a member of the Ferrari Young Driver Academy.

“I enjoy it very much, but I’m always scared,” says the proud father. “With my character, I’m very emotional, and to follow it from outside is difficult. But he’s doing a good job, he’s out of the house, he’s living in Maranello – in the Enzo Ferrari house at the track, actually. And he’s learning his job.”

We meet at the Malaysian GP, where Giuliano is contesting the GP3 support race, and our venue of choice is the Pirelli hospitality building. Until recently Alesi served as an ambassador for the tyre company, and he’s still a welcome visitor at one of F1’s Italian-flavoured boltholes. At the chef’s suggestion, lunch for both of us is a simple dish of steak and potatoes, which Jean accompanies with a glass of sparkling mineral water. It’s an appropriate place to discuss the Alesi family’s Sicilian roots – and what took them to France.

“My father was doing carrosserie,” Jean says. “It was very limited in Sicily, because there was nothing really happening there. He didn’t want to move to northern Italy, because when you’re from the south they treat you like you’re from Africa! He moved to Avignon as there was a small community of Sicilians, and by the way that is the reason he married my mother – she is from a Sicilian family, same story basically.”

Alesi won his first title – French F3 – back in 1987

Motorsport Images/Sutton

Growing up, did he feel more French or Italian? “I never thought about that, except the fact that France was very nationalistic. I was named Giovanni Alesi, and when I went to school I stated to have some light criticism from my colleagues. So when I was seven we decided to change from Giovanni to Jean, and my brother from Giuseppe to José.

“He has always been supportive of me in everything since I was born. When I was young and going to school I asked him to carry my bag, and he ended up carrying my bag with me on his shoulders.

“Of course, to be as successful as my father has been, it means a lot of sacrifice and work. He was working day and night in the garage, and my mother was helping him with all the paperwork. When we finished school my mother was picking us up, and then back to the garage. At the time we did out homework there! So I was really loving cars.

“At the weekends my father was sometimes doing rallies and hillclimbs. He started with a Vespa 400, a very small car, and then he finished in ’73 with a Chevrolet Camaro. When he was not able to race some weekends he would give his car to his friend, Jean Ragnotti, who is from Avignon as well. But most of the time it came back destroyed. I cried when I saw Ragnotti coming to our home, ‘Please don’t give the car to him, he will destroy it!’

“I was following the big events like the start of Le Mans, because in France it was very popular. And then F1, I remember this moment very well – we had a conversation at home and my father said, ‘We have a crazy driver now at Ferrari, he’s unbelievable, the way he drives.’ It was Gilles Villeneuve. And then I started to watch.

“I was 16 when I started karting, very late. For me it was a way to start playing, not really serious racing. We decided to do a category called Classe Bleue, it was very cheap, the same Continental tyres for the whole season. The races were on supermarket car parks. Maybe that was the reason why I was not very interested in set-up. I was not changing anything on my kart, but the shape of the track was changing all the time when someone hit the barrier, so we just had to adapt our driving style to the track!”

In 1983, aged 18, Alesi embarked on a season in the French Renault 5 Turbo series, and after a low-key start he won a race at Nogaro in September. The next step was single-seaters.

“I did the Winfield School in Paul Ricard, trying to win a budget. That was really the beginning of my life. The regulation was that the top five drivers had five laps to prepare the car, and five timed laps. In the five timed laps, if you spin, you’re out. I was the one before last, and the last one was Eric Bernard. I was fastest of the first four. Bernard did first lap, second lap, third lap and spun. Then he restarted, and he set a faster lap than me.

“Normally I was supposed to have the Elf drive, but the jury said, ‘No, no, we have to change it. Eric Bernard and Jean Alesi do it again.’ When you’re young like that, you’re not really prepared. In my mind I was already winning. We went, both of us, back on track. And he was faster than me, so they gave the Volant Elf to him.

Maiden F3000 season in 1988 blended promise with frustration

Motorsport Images/Sutton

“It was an embarrassing moment, because my father started to be very upset with the people there. At the time the big boss of Elf, François Guiter, was like a king in France. My father said to Guiter, ‘It’s a French mafia’ and Guiter replied, ‘The mafia is in Sicily!’ And I said, ‘Oh no…’

“In the car my father said, ‘Jean, if you want to continue in this business, I want you to be better than them – always. Do what you want, but you have to be at the top. Because if you’re not, we stop.’ So we bought a Formula Renault, and we ran it from our garage.”

Alesi spent 1984 and ’85 in the category, and in his second year he logged five podium finishes and finished fifth in the championship.

“The first two seasons were difficult for me. But I’m sure at the time they were cheating with the engines, because we had turbos. It was a bit weird. So then we said, ‘Let’s move to F3, but let’s do it differently.’ Everybody had a Martini, or a Ralt. We decided to get a Dallara. It was me and one guy from the garage, who I was taking only for the weekend. I was driving the truck with our caravan behind. And I did the first season like that. I won two races, at Albi and Le Mans, and at the end of the season, I was second.”

That year Alesi changed his helmet design in honour of Elio de Angelis, who lost his life in a testing accident at Paul Ricard.

“When he had the accident, I was in Pau. When you are on a racetrack, and you have the news that a driver is hurt, it goes even more in your heart. You know when there is a war, and the flag goes down, and there’s somebody else who picks the flag up? For me his helmet was a kind of flag. I take your flag and I put it on. I changed it a little bit, so as not to have it 100 per cent like him, but the spirit of the helmet was based on his.”

For 1987 Alesi earned support from Marlboro, which meant joining the ORECA team. He wasn’t happy with the Martini chassis, and had to persuade team boss Hugues de Chaunac to dump it and take the Dallara he’d used the previous year. Once armed with his familiar old car, Jean was the dominant force. As French F3 champion he was then invited to a crucial Marlboro F3000 test day at Donington, where 1988 drives with Onyx and ORECA were up for grabs.

“We had 30 laps each, and one set of new tyres, whenever we wanted. I was not speaking English at the time. Big problem, because the first one-to-one was with James Hunt, and then with Ron Dennis! I tried to speak, to explain my story, but it was not easy. Then I moved to the car, and I did the best lap time of the day. And I had the Marlboro budget to do F3000 the following year with de Chaunac.

“But it was not good, except Pau, where I managed to finish second. We faced some technical issues, we changed from March to Reynard. Then we had an argument with de Chaunac, and he said, ‘I cannot take you for next year, you have to find another seat.’ I was really finished. So I said to my brother, ‘Do you think we can do Macau? If it goes well, we’ll find something’.”

Alesi was set for aggregate victory in the street race when it all went wrong in the second heat: “On the last lap I had a tyre explode on the straight, and I finished on three wheels. Eddie Jordan came to my brother, and he said, ‘I like that, because he’s not giving up. What’s he doing next year?’ And José said, ‘Nothing, we are looking for something,’ And Eddie said, ‘Let’s see what we can do.’ I went to England, we did a deal and my life changed…”

Creating a sensation at Tyrrell in 1989

Motorsport Images

At the time Jordan was just starting to put the pieces of an F1 project together. In the interim his focus was on his own Camel-backed F3000 team, while also helping an endless stream of ambitious youngsters who were happy to benefit from his entrepreneurial skills, albeit at a price.

“There are so many stories about him, but mine is different from what I hear sometimes. He was not looking for money, he was looking for success. And he was really looking after me like a son. I lived in a very small room in his house, even though he had small kids at the time, and he made me feel at home. Every morning I went to the office with him, trying to improve my English with the mechanics. And he understood that I was a real fighter. I never treated him as a manager, I treated him as a father. I had full trust in him. I never asked, ‘How much?’ I just asked him for a good drive, and for him to take me to F1.”

The first four F3000 races of 1989 included a victory at Pau. Then in July an F1 seat opened at Tyrrell, when the team attracted Camel support and long-time Marlboro man Michele Alboreto opted out. Jordan was quick to pounce, agreeing a one-race deal with Ken Tyrrell for Jean to do the French GP. Also making their F1 debuts that weekend were Alesi’s F3000 team-mate Martin Donnelly – and long-time rival Eric Bernard.

“Ken had to make a presentation for Camel. My old friend François Guiter, who was very close to Ken, went to him and said, ‘I’m happy you took a French driver, but you didn’t take the right one.’ Ken didn’t argue. On Friday I was seventh in the first qualifying session. Everybody was happy, especially me! Ken went to Guiter and he said, ‘When you have a better one than him, call me…’”

After a frustrating Saturday qualifying session (“Maybe because I was overexcited”) Alesi started only 16th, but he went on to finish an astonishing fourth, having run as high as second for a few laps. Within days he had signed a Tyrrell contract extending into 1990, with options for ’91 and ’92. He had to miss the Belgian and Portuguese GPs as Jordan insisted that F3000 take priority, and he duly won the title. And thanks to a fifth place in Italy and fourth in Spain, he finished ninth in the world championship, having started just eight of the 16 rounds. This sensational opening to his F1 career had not gone unnoticed.

“In the winter of 1989-90, Frank Williams decided to take me for 1991, ’92 and ’93. They signed a contract with Eddie. And inside there was a paragraph underlining that the deal would be announced at the French GP. If it wasn’t done there, then the contract would become an option until the end of September.

“When he read it my lawyer said, ‘Take it out.’ I called Frank and he said, ‘I cannot do it differently, because I didn’t say anything to Renault, and it’s Renault who pays the drivers. I need to keep that because the announcement is going to be made in Paul Ricard, 100 per cent. From now to July I have enough time to convince them to take you. So that is just lawyer’s talk.’ My lawyer said, ‘Do you trust him?’ I said, ‘I have to, he’s Frank Williams.’ So I signed, and gave it back.”

Meanwhile Jean remained a Tyrrell driver for 1990, and hopes were high. The team switched from Goodyear to Pirelli just before the season opener in Phoenix – with no time for testing. “I didn’t qualify well because of my inexperience – I touched the wall twice – so I was not precise. But I was quite confident for the race. I started fourth and had a very good first lap. Fourth, third, second and then I led. My thought was, ‘I hope my friends in Avignon are watching the race!’

“Suddenly I started to see some red coming in the mirrors, and I understood it was Ayrton, because I had the pit board. Then he caught me, and I thought. ‘Let’s give him a hard time.’ I was not weaving, but I was pushing to make it difficult to overtake. I had such a good time…”

Senna eventually passed Alesi, who then had the cheek to nip back by at the next corner, before bowing to the inevitable on the following lap. He still finished second, and by now everyone was paying attention.

He enjoyed the family ambience at Sauber for two seasons

Motorsport Images

“After Imola, and before Monaco, Cesare Fiorio asked me to come to Maranello. I was with my brother, and on the way I said to José, ‘If he asks me to go to Ferrari, what do I do?’ He said, ‘Nothing, you cannot do it.’ And Fiorio said, ‘We want to have you for 1991, ’92 and ’93.’ I said, ‘Mr Fiorio, I’m sorry I have a contract already.’ He said, ‘With Tyrrell?’ I said, ‘No, with another top team, I cannot say.’ He started to get upset, and he said to me, ‘You cannot say no to Ferrari.’ I said, ‘It’s not that I cannot say no, but it’s not possible’.”

Ferrari’s interest was stoked further when Alesi logged another excellent second place, in Monaco. “After Phoenix Frank had said, ‘It’s fantastic, exciting,’ and so on. Then Monaco, the same. That was in May, and I said to Frank, ‘Is it all OK?’ and he said, ‘Yeah, yeah.’ The week before Paul Ricard I called Frank, and he said, ‘We have to set it for Friday or Saturday’.”

At the start of the French GP weekend, Alesi was roped in to a Marlboro event as a last-minute replacement for Alain Prost. “Fiorio was there, and he said ‘Frank will not make the announcement this weekend. You’ve signed with him, but he’s looking for Senna.’ So I went back to Frank, told him what happened to me a few minutes before and he said Fiorio was a bullshitter!

“At the time I was very close to Nelson Piquet, and I told him, ‘I have a secret to tell you about what’s happened to me.’ I explained. He said, ‘Jean you’re an idiot!’ ‘Okay, what can I do now?’ He said, ‘Go to Ferrari and tell them to make a proposition, and you take it to Frank and show him. If he doesn’t sign you immediately, go to Ferrari.’

“Silverstone was next and I went to the hotel of Ferrari president Piero Fusaro. I said, ‘Mr Fusaro, I have a contract with Williams. I cannot accept your offer the way things stand right now.’ I said I wanted to drive for him, so he made me a proposition.

“I went to Frank and showed him the Ferrari proposition. When he saw ‘Ferrari’ he went completely mad. ‘How can you sign, they’re bullshitting, they’re trying to f**k you up!’

“I said, ‘Look Frank, you sign me, and that is it, finished.’ He said, ‘No, you have a contract until September…’ I said, ‘I will not wait. Confirm now – or not at all.’ In September it would have been possible for him to say, ‘We don’t want you.’ And where would I go? So I went back to Benetton to see Nelson.

“He went mad. ‘September! You show me the offer of Ferrari.’ He took it, said, ‘The price is not good’ and added one million more. He also inserted an F40 road car and a fixed three-year deal. So I changed everything. I went to Fusaro, and gave him the new contract. He said, ‘For a young driver, you are really prepared.’ It was Nelson who did everything! Anyway, you know the end of the story. I moved to Ferrari, Frank had Prost’s F1 car as compensation, plus some money. I had my F40 and a good contract, but my intention had been to go to Williams…”

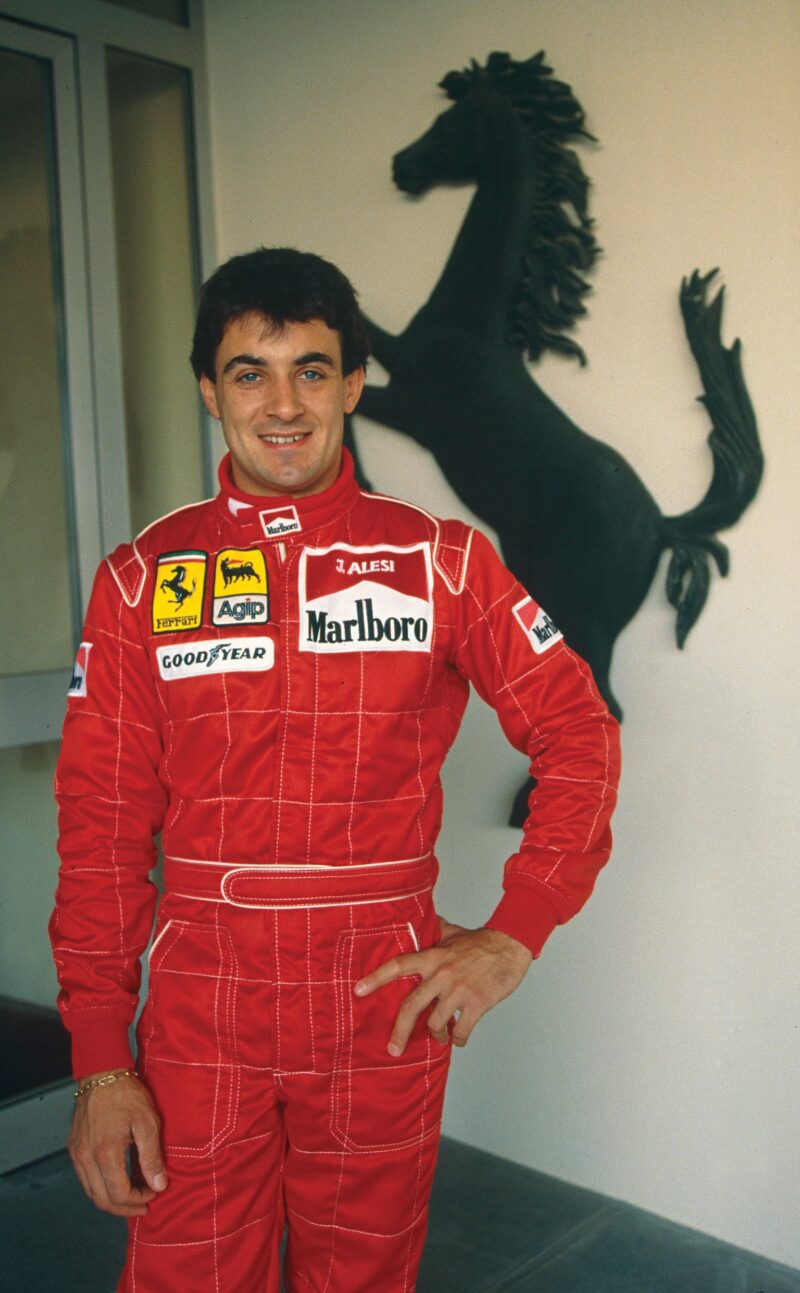

Ferrari new recruit, 1991

Motorsport Images

In the end Frank signed Nigel Mansell – the man Alesi replaced at Ferrari.

At this point in our conversation the Pirelli hospitality building is filling up with hungry technicians and tyre fitters, and our table is required. At Jean’s suggestion we take a break and move along the Sepang paddock, with appropriate timing, to Ferrari.

“I had a terrible 1990 season, because every race I was in Frank’s motorhome, Ferrari’s motorhome… It was not nice. When it finally happened, I was of course extremely happy. I was just back to what I wanted, to be a driver. My team-mate was Alain, and that was also very interesting because of the way he fought with Senna, and I wanted to learn as much as possible from him. I was very happy to be with him, and I was in a team where I was testing non-stop, and I had freedom to do what I wanted.”

He very nearly won the 1991 Belgian GP, only to suffer a late engine failure while running ahead of Senna’s ailing McLaren.

“We had a very fragile car, and technically there was an internal fight about whether we should work on active suspension. In the end everything collapsed! It was a shame, because for me Fiorio was very capable. He had a racing spirit, he had a racing view, and for the time he was definitely a super team boss. But Alain did not always get on with him…”

Prost was sacked before the last race of the year. Then towards the end of a difficult ’92 season alongside Ivan Capelli and Nicola Larini, Alesi learned that he was to be partnered by Gerhard Berger in ’93.

“I was testing in Estoril, and in the newspaper it was, ‘Gerhard back to Ferrari, number one driver, leading the development of the car, blah, blah.’ The testing was starting at 9am, and at 9.15am I was on the phone to Niki Lauda [then a Maranello advisor]. I said, ‘Niki, what kind of respect do you have for me? Why do I need to be number two, and Gerhard is coming from McLaren, where he has always been behind Ayrton?’

First of two Le Mans appearances, Here in 1989

Motorsport Images

“He said, ‘Let me speak with Luca di Montezemolo, and we’ll call you back.’ Then Montezemolo called, and said, ‘Look Jean, it’s not like you read, everything will be as usual in the team, and if you are upset, I’ll give you an F1 car.’ I said, ‘I’m not upset, I’m disappointed.’ ‘Don’t be disappointed, you’ll have the car, now shut up and go and drive!’ So I have a ’92 F1 car at my house…”

In the middle of that 1993 season Jean Todt arrived at Ferrari: “I was a bit scared, because Jean had a very tough reputation. Not tough in a bad way, but a disciplined guy. It was always ‘Mr Todt’, never ‘Jean’. He was everywhere at first – here, there, in the garage, very efficient.”

The first signs of a turnaround came when Berger won at Hockenheim in 1994. That year Alesi took pole at Monza, but a first GP win continued to escape him. Meanwhile he had to watch first Mansell and then Prost win world championships for Williams, while Damon Hill became a title contender. He logged 13 podiums over four and bit seasons at Ferrari before luck finally went his way at the 1995 Canadian GP.

“That was a big day because I’d had retirements when leading Grands Prix, but at last everything held together. And it was my birthday, so it was unbelievable.”

Alesi’s relationship with Todt began to unravel when it became clear that Michael Schumacher was leaving Benetton to join Ferrari in 1995, and he would have to make way. In the end, they swapped seats.

“Flavio Briatore made me aware of the Michael situation. When I asked the team what was going on, they never said it was happening. It was the right choice to have Michael, but they could have told me. Flavio said, ‘If he leaves, please look at us.’ I thought, ‘Why not?’ Everything moved after that.”

Monaco 1997, prior to a race-ending spin

Motorsport Images

What Alesi didn’t expect was that, wary of partnering Schumacher, Berger would jump ship and join him at Benetton: “In the end we respected each other very well, he was doing his job and I was doing mine. Really, I appreciate him a lot. We spent five years together and I scored 40 points more than him…”

The two Benetton seasons were frustrating – Jean logged 13 podium finishes and took pole at Monza in ’97, but once again a few potential wins slipped away. By the end of that year he had fallen out with Briatore and decided to move on for ’98.

“At first I went to Stewart. I spoke with Paul and Jackie, but they said, ‘We’re sorry, but we’re not prepared for you.’ It was just a small team. So then I went to Peter Sauber, and I said, ‘Please give me a car and I will do my best.’ He was surprised, but I wanted to have a challenge. I had a super time. Like Tyrrell, you know? Very good atmosphere, no politics, and I really felt at home. I had a different target, and anyway I put the car on the podium in Spa, plus I scored some very good points.”

The 1999 season was less satisfactory, and for 2000 Alesi was tempted away by the prospect of racing for his first Ferrari team-mate.

“I wanted to finish my career with Alain, and give France a successful team – like Ligier had been. When I signed I was extremely happy and excited, but with Peugeot engines there was no chance. That was disappointing.”

Indy 500 adventure proved a major letdown in 2012

Motorsport Images

In a disastrous first season he failed to score a point, although he managed to qualify seventh in Monaco. The following year got off to a better start on track, with Ferrari power, but the team was falling apart and Alesi left after the 2001 German GP. He then agreed to do the last five races of 2001 for his old pal Eddie Jordan, who had sacked Heinz-Harald Frentzen: “That was good, especially the race at Spa, when I finished sixth and had a very good fight with Ralf Schumacher in the last laps. It was not a bad car.”

Alesi knew there was no Jordan seat for 2002 – Honda protégé Takuma Sato was coming in – and just before the Suzuka finale he made a spontaneous decision to retire.

“I was at a Bridgestone press conference in Tokyo when a Japanese journalist asked, ‘If Sato is driving for Jordan next year, what will you do?’ I didn’t like the way he asked me that. So I said, ‘I will stop.’ Michael and Rubens were next to me, and they looked across and said, ‘Really?’ I said, ‘If Sato is taking my drive, it means it’s better to stop.’ And I did.”

That last race ended early when a spinning Kimi Räikkönen took Alesi into the barriers. I happened to be with him as he left the paddock gates after the flag. He gave a mock celebratory jump, saying “I’m free!” – and handed me his season pass. It’s a treasured piece of memorabilia.

Jean says that he had no future plans, but one soon emerged.

“In Suzuka Norbert Haug from Mercedes said ‘Please consider the DTM. It’s good, you will have fun, it’s for you.’ So I went to have a look and drove the car. It was very enjoyable, and I accepted the proposition. I raced five years for them, and I had a good time. They treated me very well, and I had a super contact with the German fans.”

He had a bonus early in his first season when Haug invited him to do some engine testing with McLaren.

“It was fantastic. I did five days and felt important again. I drove the old car at Paul Ricard, and then in Mugello they asked me to drive the new car. Adrian [Newey] had some new ideas, and it was not quick. As long as I was there to explain the driveability of the engine, it was okay. But when I started to say the chassis was bending, they said, ‘Thank you, bye-bye!’ I was upset. I said to Ron Dennis, ‘You asked me to tell you what’s happening. I am saying it to you, not to the press…’”

Back with Ferrari, now at Goodwood in 2013

Motorsport Images

He would win five DTM races, but life wasn’t always straightforward: “Mercedes had this very tough way to speak to the drivers. They had drivers like a football team – goalkeeper, defender and striker. And when they started to speak to me like that, I was looking at them, ‘Are you nuts? I do my race. I race for Mercedes, but I’m not here to block Audi drivers. No way!’”

After being shifted from HWA to the second division Persson team for 2006 – where he had to make do with a year-old car – he decided that five years was enough. In 2008-09 he appeared with other ex-F1 drivers in the Speedcar series, supporting some flyaway GPs, before the organisation folded. Then in 2010 he raced a Ferrari F430 GT with Giancarlo Fisichella, and returned to Le Mans for the first time since 1989. He didn’t enjoy the experience.

“I love to drive, but I didn’t want to be mixed with gentleman drivers and I didn’t want to be mixed with young drivers, because it doesn’t match. I would be very happy or keen to have a ‘legends’ race with Gerhard, David Coulthard, Johnny Herbert. I don’t want to be with dentists or lawyers. When I went to the driver briefing in Le Mans, I thought I was in a party! Guys in overalls with big stomachs… I realised how difficult the race would be, because you’d see cars and wouldn’t know if it’s a professional or a wanker driving.”

Alesi’s last on-track adventure was that 2012 Indianapolis 500, a legacy of his role as an ambassador for Lotus. Unfortunately the engine that the Norfolk marque had badged was hopeless: “It was almost impossible to keep the car in the power band and the car felt absolutely dead. It was so sad for me…”

After qualifying 33rd Alesi ran for just a few laps in the race before he was forced to park due to a simple lack of pace. He then called time on his career to focus on helping Giuliano.

Since then he has kept himself busy by conducting interviews with key F1 figures for Canal Plus, while as a hobby he owns a vineyard in Avignon and, along with Sylvester Stallone, he’s a shareholder in the upmarket Montegrappa pen company. He also keeps an eye on the family bodywork business.

“My father is still there. He is 76, but he is very busy, because we now have more than 70 people working in the carrosserie. It’s his baby, and my brother is looking after the financial side of things.”

As for his career, he says even with the benefit of hindsight he wouldn’t have done anything differently – including that decision to go to Ferrari.

“I have absolutely no regrets, honestly. The Williams story is part of my life. You cannot look back. It’s like if you had an offer to buy a 250GTO 25 years ago for $10,000, and now it costs $35m. If it didn’t happen, it’s destiny. But the way everything happened is not what I expected.”