The Ralt (Ron and Austin Lewis Tauranac) Special was powered by a Norton 500cc engine the brothers would continually refine. The same went for the chassis, with Ron given a lesson on the car’s competition debut at Hawkesbury Hill Climb in 1950. “I’d read that inter-leaf friction was all you needed for a damper,” he says. “I didn’t have money to buy dampers, so believed what I read. Before the start of the hill, there was a ditch near the edge of the road. With no restriction on the droop, the wheel went into that, rolled underneath and tossed me over.”

He awoke in hospital with 14 facial stitches.

Through the Ralt Special, Ron met fellow RAAF ex-serviceman, racer and engineer Jack Brabham, in 1951. Brabham was already an established speedway star and a rising talent in circuit racing. He also had a knack for delighting sponsors, in an age before sponsorship was permitted. But the stardom wasn’t all one-way.

In the 1954 NSW hill climb championship, Brabham lined up his Cooper-Bristol against Tauranac’s spindly 500cc Ralt 1, by now running on nitro-methane. Brabham finished second, sandwiched between winner Ron and his brother Austin’s special, Ralt 2.

Brabham went to the UK in 1955, initially racing an ex-Peter Whitehead Cooper-Alta F2 but soon working, and driving, for Cooper.

The friendship with Tauranac continued in a technical collaboration conducted by airmail.

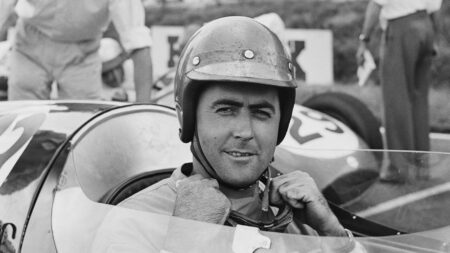

Brabham competing in 1956 at Oulton Park at the wheel of a Cooper T41

Michael Tee / Getty Images

Early in 1960, Tauranac was preparing five Ralt single-seater chassis (eventually to surface as Lynx Formula Juniors). Brabham, who felt he was outgrowing the autocratic atmosphere under Charlie Cooper, had a better idea. In The Jack Brabham Story, he wrote: “Ron’s design and manufacturing capabilities were always central to my ideas of independence. As 1959 world champion, my new garage business in Chessington had got off to a good start and during that winter I was able to offer Ron a job in Britain. He was the only bloke with whom I’d have gone into partnership. He was conscientious to a fault and peerlessly straight.”

Ron put Norma and four-year-old daughter Jann on a boat to England. He was to fly via America, where he race-engineered Jack’s Cooper Monaco at Riverside on April 3. Tauranac had more than engineering on his mind. “I thought I was going to drive in England,” he says. “That was one of the reasons I went. But when I got over there, I realised that if I drove and anything happened to me – we had no money, so what would my wife and child do? I decided I couldn’t take the risk.” Was he a good driver? “I was quick,” he says, “but a bit too aggressive.”

Brabham’s Cooper contract meant Tauranac had to operate in secrecy. By day he tuned Triumph Heralds and Hillman Imps, for Jack Brabham Motors. At night in his Surbiton flat, he designed a Formula Junior for Motor Racing Developments, their 50/50 joint venture.

The MRD Formula Junior was ready in the summer of ’61, Australian Gavin Youl finishing second to Alan Rees’ Lotus on its debut, the attention forcing Brabham to downplay the MRD project as a kit-car being developed for the Australian market. Charlie Cooper wasn’t fooled. “Suddenly we had to build an F1 car,” Tauranac says. “We’d wanted to do that, but it happened a bit earlier than we expected.”

Jack and Ron: “We weren’t talkers”

Getty Images

The Formula Junior was renamed the Brabham BT1 and Jack drove customer Lotuses until he could race the BT3 F1 car in the 1962 German GP. Tauranac, whose second daughter Julie arrived in 1962, just toiled. “I worked days and well into the night,” he says. “Sometimes I’d go home for breakfast and then back to work again…”

How did he rate Brabham, the driver? “He was always good,” he says. “He never won at a speed greater than necessary… He just tried to save the car. He knew what made things work and how to preserve them. He was the best technical driver.

“When [Jochen] Rindt was racing for us, he was a little bit quicker than Jack – not a lot – but we’d have to take his cylinder head off and reset all the valve gear after every race. Jack’s would just go on forever.”

Were they the perfect partnership? “I don’t know about perfect, but it worked. We weren’t talkers, either of us. We’d speak if we had something to say, but never had an argument.”

Tauranac viewed his job as developing a racing car business. This mindset would colour designs that often appeared conservative, particularly when framed against the avant-garde efforts of Colin Chapman at Lotus.

In 1964, Dan Gurney scored Brabham’s first championship grand prix victory in France, with Jack third. It satisfied Tauranac more that, in the same year, Brabham built and sold about 50 cars, spanning several categories. F2 was booming and, while running the Cosworth-Ford SCA in 1964, Brabham was cultivating a relationship with Honda.

“Jack met Honda when he was at Cooper,” Tauranac says. “They’d bought something [a Cooper-Climax] and wanted some help, I think. On his way to the Tasman Series, Jack called in there. So when they were going to bring their F2 engine along, they contacted us.

“I built a car [the BT16] around it and towards the end of 1965, we tested it. We told them what needed fixing and they agreed. In ’66 we won everything with that.”

Brabham on the way to victory at Zandvoort in his championship year of ’66

Getty Images

Indeed, in F2 the ‘works’ Brabham BT18-Hondas of Jack and team-mate Denny Hulme won all but one of the championship rounds. Rising star Jochen Rindt pipped the boss by two-tenths of a second at the Brands Hatch final, in a privateer Brabham-Cosworth.

“Instead of leading like other drivers, Jack always dropped back and let them pass to make a proper race,” Ron says. “It wasn’t just for the show – it stopped us destroying F2, because we were the only ones with that car and engine.”

In 1966, of course, domination in F2 and F3 was merely the icing on the cake. Jack won his third world championship, becoming the first to take the title in a car bearing his own name. Tauranac had designed the BT19 F1 chassis to accept the stillborn Coventry-Climax flat-16. Meanwhile, Jack discovered the Oldsmobile F85 alloy-block V8 and had been pushing Repco to develop it as a 2.5-litre Tasman unit.

“I had to use that chassis and accommodate the Repco,” Ron says, “so that influenced the design of the cylinder head. They couldn’t do the engine the way it was intended.”