Lunch with... Rick Mears

The great American racer not only won four Indianapolis 500s, but remains one of the most modest men in racing to this day

Jessica Milligan

These Lunch With…. pieces start out as long and often colourful one-to-one conversations, over a pleasant meal. But they end up in black and white, as printed words. So I can give you what the man says, but sometimes it’s harder to communicate how he says it. When I ask Rick Mears to talk me through his career, he can hardly avoid his four Indianapolis 500 victories, an unbeaten tally equalled only by two others, AJ Foyt and Al Unser. Then there are his record six Indy 500 poles, and his 25 other major Indycar victories. But he describes it all with such laid-back modesty, such self-deprecating humour, that what on paper may sound arrogant or self-satisfied is in fact the very opposite. You have to remind yourself that you’re sitting not with a studious schoolmaster, or a sympathetic family doctor, but with one of the greatest American racers of all time.

Something else that singles Rick out is that he never used his success as a lever to move on in search of ever greater demands and dollars. He spent 15 years, his entire racing career apart from a couple of apprentice seasons, with the same team. And today, 20 years after he retired, that team — Penske Racing — still retains him as a valued consultant and driver advisor. So it’s at the Penske headquarters in Charlotte, North Carolina that we meet, in a crisp, businesslike conference room. Rick tells me we can take our time: he has set aside all day to talk to me.

He was born in 1951, the younger of two brothers, in Wichita, Kansas, where his father was a mechanic at the local Chevy dealership. Bill Mears supplemented his income by racing jalopies up to six nights a week on local fairground ovals and dirt tracks: he’d turn up, find a car to drive, and split the winnings with the owner. In 1955 the family moved west to find a new life in California, ending up in hot and dusty Bakersfield where Bill found work as a backhoe driver. A backhoe is what we Brits would call an excavator, a piece of heavy earthmoving equipment with a scoop at the front and an articulated bucket at the back.

By 1960 Bill had saved enough to buy his own backhoe, and turned away from racing. Rick remembers: “One night he won the hundred-lap main event, won the trophy dash, set the fastest lap, and all that earned him was just $60 to split with the owner. He knew that if he broke an arm and couldn’t operate the tractor, he couldn’t put food on the table. He decided it wasn’t worth the risk for 30 bucks.”

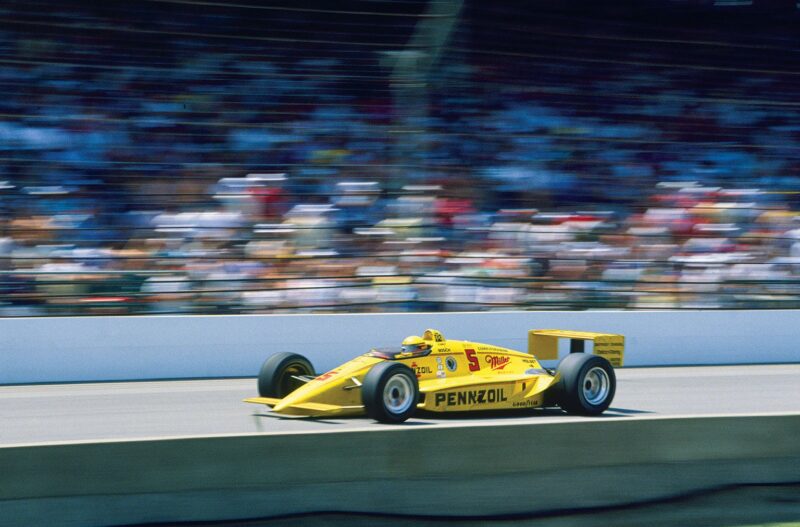

Indy 1988: after falling to 10th due to handling problems , Rick recovered to win the race for a third time

Motorsport Images

But Bill and his wife Skip were also into motorcycles. At weekends the family would take off, Rick on the back of Skip’s Ariel Square Four and elder brother Roger on the back of Bill’s 500 Matchless, and Rick was still a ED junior in high school when he started racing motocross bikes. “One night somebody went down in front of me, I came off, somebody else ran me over. So Mom told Dad she’d be happier if I had four wheels and a roll cage around me. We’d seen sprint buggies racing at Ascot Park, the half-mile dirt oval south of Los Angeles, and when we looked around the paddock I didn’t realise that Dad was working out who was running quick, and exactly what they were running, because at heart he was still a racer. In the car going home Dad says, ‘I’ll make a deal with you. Give up racing motorcycles and we’ll build a racing buggy.

One buggy became two, so Roger and Rick both raced the VW-engined machines. In his second year, still only 19, Rick won a local championship, and then some long-distance desert events, culminating in the Baja 500. But funds were tight, and if Rick or Roger didn’t win any prize money one weekend they couldn’t afford to run the next — which helped to hone Rick’s silky-smooth style, because he always knew he had to make it to the finish. Meanwhile Bill taught Roger and Rick how to operate a backhoe, and the boys dug ditches all week to pay for their fun. “Desert racing is far more demanding than people realise. It taught me so much. You can’t memorise a 100-mile lap, and you have to adapt to surfaces that vary from asphalt to sand to dirt to mud, even snow. After that Indy racing seemed so easy: nice smooth surface, no ruts or holes, and just four hours, when I’d been used to 10 or 12 without a break.”

On the way to 1988 Indy glory

Motorsport Images

In 1972, when Rick was still only 20, he was invited to compete in an off-road race in Japan, styled the Japanese Grand Prix and run on a dirt course around the Oshima Island volcano. “I’d never been in an aeroplane before. Parnelli Jones, my boyhood hero, had retired from Indy racing but was still doing off-road. Well, I won that race. Parnelli was second. I consider it my first big win.” Meanwhile, brother Roger took his VWpowered buggy to the famed Pike’s Peak hillclimb and won it outright, nimbly beating all the big alcohol-fuelled V8 single-seaters. In 1976 Rick followed him, winning in a Porschepowered buggy. “Pike’s Peak was wonderful: rushing into those tight corners on the loose and all you could see ahead was blue sky and clouds. Almost all of it was dirt, but they’ve ruined it now, most of it’s paved.”

One day, passing the old Ontario Speedway, Rick and Roger paused to watch practice for an upcoming USAC race. They’d never seen Indycars before. “I didn’t even dream of getting into one of those things: way, way out of my league. But a friend said, ‘Why not take my old Formula Vee to the SCCA school at Riverside and get your licence?’ When I get there this SCCA guy leans into the cockpit and says, ‘Listen, son, this is a lot different from just bouncing across a few rocks in the desert.’ But it seemed pretty straight-forward to me. The second day it rained. I’d never run hard on pavement in the rain, but I’m going around OK and they pull me in, tell me I’m going too fast. I thought that’s what we were there for.”

In 1976, after some good races in that old Vee, Rick was offered a ride in a SuperVee, duly won the local championship, and qualified for the Road Atlanta run-offs at the end of the season. But, thanks to racewear tycoon and racer Bill Simpson, he never got there.

“Simpson’s one of those guys, either he likes you or he doesn’t. It seems the Simpson’s desert rep kept saying to him, ‘You got to watch this kid Mears.’ Finally the rep got me to a trade show to meet Simpson. Simpson turned round, looked at me, grunted, ‘Don’t tell me, another of those damn’ off-road racers.’ I thought, ‘What a jerk.’ Then I saw him at Willow Springs, I was testing the SuperVee, and he was going round in his Formula 5000 car. Next day he’s on the phone. ‘Hey, Mears, can you get off work next Wednesday? I want you to test my 5000.’ I said, ‘Yeah, I think I can get off work’.

“I’d never driven anything with power; my tongue used to hang out looking at Formula Atlantics. But with the F5000 I just listened to what the car was telling me. I went quicker and quicker, and Simpson said, ‘This boy’s going to go off at Turn 9.’ Sure enough, two laps later I went off at Turn 9. But what sold Simpson was I went off, got on the dirt, never lifted, got back on and kept going. I was at home on the dirt, it didn’t really bother me.” Simpson was no slouch — he managed 11 top-ten finishes in Indycar — but he was amazed when the young backhoe worker ended up 2.5sec a lap faster than him that day.

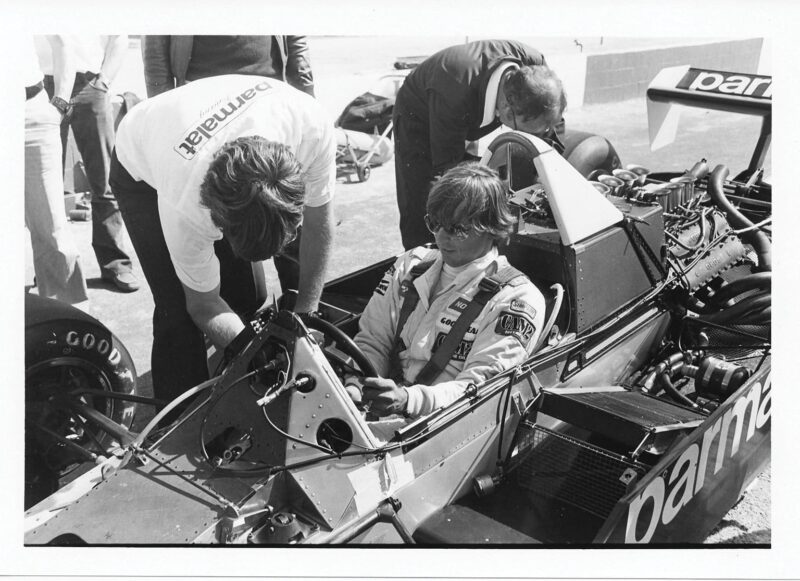

Brabham test organised by Ecclestone tempted Mears to consider a move to F1

“So Simpson says, ‘I want to sign you up on a contract. F5000 and/or Indycar. Ten years.’ I’d never had a contract with anybody in my life, but it sounded pretty good, so I signed. Then in my first race for him the F5000 swapped ends on the first lap, and I crashed. I was mortified. Next day he calls: ‘Quit beatin’ yourself up, we found what happened.’ Between qualifying and the race they’d moved the rear suspension pickup points to try to improve the understeer. First time I stood on it the wishbones fouled the exhaust headers and the rear wheels came off the ground. After that I never cared about a crash, as long as I knew why it had happened.”

Then Simpson put Rick down to drive his back-up Eagle in a major Indycar race, the California 500 at Ontario — where, barely two years earlier, Rick had first seen an Indycar. At first USAC President Dick King refused to let Mears run, citing his lack of experience. “So Simpson said he’d pay for any damage I did. USAC made him put up his house as collateral! I finished eighth. The big horsepower didn’t worry me. You can never have too much power. To me that was the fun part, trying to keep things hooked up. Today, with all the driver aids and aerodynamic grip, I think we miss out. We’d be better off with less grip and more power, to put things back in the driver’s hands.”

Simpson sold the Eagle to Art Sugai, on condition Mears drove it, and Rick prepared for his first Indy 500. “I told my landlord, ‘I’m going away for a month.’ He said, ‘Well, don’t bother coming back, we’re selling the apartment.’ And I said to the guy I was working for, ‘I have to take a month off, I’m doing Indy.’ He said, ‘That’s great, but you won’t have a job when you get back.’ By then I had a wife and two kids. If something like that happened to me today I’d probably hang myself, but I was young, and I reckoned when the money ran out I could always find a backhoe somewhere. So I packed our world into a U-haul trailer behind our old Chevy, and set off for Indiana.

He impressed the team by going 1sec per lap faster than Piquet

“But Sugai didn’t really have the money to run the team properly. Parts were tired, things started breaking, engines failed, and I didn’t qualify for the race. In fact it was a blessing, because I’d just have been another also-ran, or another retirement. Better to come back next year, qualify on the front row and get Rookie of the Year. [Which he did.] But I was really demoralised. I tried to qualify using a borrowed engine, and I was about one mile an hour away from making the show. I was sitting on the wall trying to figure out what to do, and Roger Penske walks by. He says, ‘Hey, how you doing’? I say, ‘It doesn’t matter what I do, I’m a mile short, and we only got one more shot.’ He says, ‘Well, best thing would be, just don’t hit the wall.’ Then he walks on. That was my first conversation with Roger.

“After that I had no money, no job, no house, no nothing. Rick Galles, who owned a dealership with Bobby Unser down in Phoenix, Arizona, said he’d give me a helping hand until I got myself set up, so I became a car salesman. As you can imagine I’m no salesman, so when people came into the showroom I just left them alone. That’s the way I like to be sold to. And a good few cars did get sold. Then Simpson sold his McLaren to Teddy Yip, and got him to run me for the rest of the season.

“Driving for Teddy my strategy was always to finish. I thought, if I can’t out-run ’em I have to out-live ’em. So I never hit the fence, I either finished or broke. On the one-mile oval at Milwaukee AJ Foyt, who was pretty much the King then, came up to put a lap on me. I saw him in my mirrors and thought, ‘OK, I’m not going to do anything stupid, I’m going to keep to my pattern, so he knows where I’ll be’. So it takes Foyt a couple of laps to get by, then he goes on and wins the race. I’ve finished fifth, my best race to date, I’m all excited and happy, and my guys say, ‘Man, what did you do to Foyt? He came by ranting and raving.’ He said, ‘You tell that Mears, if he ever tries that again ah’m gonna stick him in the fence’.

So now I’ve got the King mad at me, and I’m quaking in my boots. I see him at the next race, he’s surrounded by fans signing autographs, and I hear, ‘Hey, Mears!’ I think, ‘I’d better get this over with’, so I walk up. He puts an arm around me and says, ‘God, we had a helluva race out there in Milwaukee, didn’t we!’ That’s when I realised his bark is worse than his bite. He hates it when I say this, but Foyt’s just a big teddy bear.

“All this time Penske was watching me. Roger’s always thinking 10 years further down the road. I guess he thought, ‘Maybe we should give this kid a shot, he hasn’t been sticking it in the wall every time out’.” Penske needed a third driver for his USAC team alongside Mario Andretti and Tom Sneva, because of Andretti’s Fl commitments. But first there was the little matter of that 10-year contract with Simpson. According to Simpson, “I told Penske, ‘You put that boy in a good car, he’ll win Indy for you.’ Penske said, ‘Those are pretty bold words. What about this 10-year contract’? I said, ‘If you want him, I’ll give you the contract for nothing. I just want to see Rick in a good car’. And Rick went on and kicked everybody’s ass.”

1985 Indy 500, getting around on an electric buggy after the previous year’s crash at Sanair

Motorsport Images

Penske summoned Rick to his farmhouse by the Michigan Speedway, one of the tracks he owned. “He asked me for breakfast. I was so keen I got there two hours early, and everybody was still in their pyjamas. Roger said, ‘It’s a part-time deal, because of Mario’s Fl clashes. I’ll guarantee you at least six races, including the three big 500-milers.’ Well, I’m sitting there trying to act all professional, so I said, ‘Sounds great. Can we get it on paper?’ Roger said, ‘What for ?”Well, something I can take back and, um, get my people to look at.’ I didn’t have any people, of course, but I didn’t want to sound like I just fell off a backhoe. So Roger produced a simple letter, three pages at most, took me through it so I knew what it meant, and I said, ‘Great, let’s go.’ That’s been pretty much the extent of our contract ever since, for 35 years.”

It didn’t take long for Penske’s trust in the youngster to be vindicated. That first season he qualified on the front row at Indy — “doing a 200mph average in the PC6 was far less scary than doing 182 in the Sugai Eagle” — and was Rookie of the Year. Then he scored superb victories on the ovals at Milwaukee and Atlanta. And, to show he was equally at home on road circuits, he came on the USAC two-race trip to England, finished second to A J Foyt at Silverstone and then won at Brands Hatch, half a minute ahead of team leader Sneva after 100 dizzy laps of the short circuit.

*

The 1979 season was Rick’s first as a full-time Penske driver, alongside Bobby Unser, who replaced Sneva as team leader. “Bobby wasn’t so much of a team player over setup and stuff, he kept his cards close to his chest. He said, ‘I wasn’t put on this earth to make Mears go fast.— But it was Mears who won a sensational victory in the Indy 500 from pole, and then won at Trenton and Atlanta. And it was Mears who was crowned that year as CART Champion. As the poles and victories piled up, he took the championship twice more in the next three years. Key to this success was the relationship he built with Penske, closer than any other of Penske’s drivers save Mark Donohue, who had been killed in 1975.

“Roger never put pressure on me. He knew no-one could put more pressure on me than I did myself. Because of his reputation people used to say to me, ‘He must be tough to work for’. But all he ever asked was you put your best foot forward. Money was never an issue between us. When it was time to renew my contract Roger’d say, ‘This is what I was thinking.’ I’d say, ‘Well, I was kind of thinking that.’ And Roger’d say, ‘OK’. At the time bonuses were coming in for some drivers, so much for a top three finish, for winning Indy, for winning the championship. But I didn’t need a bonus to make me drive faster. I told Roger, `If a bonus makes me do anything I’m not doing already, I should be fired.”

Word of Rick’s smooth speed carried far beyond the American racing world, and one day Bernie Ecclestone called. “He wanted to test me in an Fl Brabham. Roger said, ‘Hey, I’m not going to stop you.’ So with his blessing I went to Paul Ricard, and I did a test alongside Nelson Piquet, who was the Brabham No 1 then” — and would be world champion for Brabham twice in the next three years. “To me, a race car is a race car. To get the best out of any car, you have to listen to what it says to you. I don’t think there are any supermen on this earth. Everybody, even an F1 driver, puts his trousers on one leg at a time. A good driver can be good in anything, even if it may take him a couple of laps to understand what an unfamiliar car is telling him.”

Different car, different culture, but Rick was straight on the pace. At Ricard he ended up within 0.5sec of Piquet’s best time. Bernie took note and a few weeks later, when the Fl teams were in the USA for the Long Beach GP, there was a further test at Riverside. This time Rick outpaced Piquet by a full second. Herbie Blash, now a senior FIA race director but then at Brabham, believes Rick was a world champion in the making. Gordon Murray, then Brabham’s designer and technical director, remembers his smoothness, and his intelligence.

More broken bones in his foot couldn’t prevent a fourth Indy win in 1991

Motorsport Images

So Bernie made a firm offer, and Rick went home to think about it. “That Brabham [the normally-aspirated Cosworth-powered BT491 didn’t have the brute horsepower of the Indycars, but its cornering speeds, braking and grip were much greater. I loved it. And Bernie’s deal was good. But I wasn’t sure about some of the egos in FL Or the extra travelling, and maybe living in Europe. I’d proved to myself I could drive an Fl car as quick as one of the top guys. I didn’t need to prove it to anyone else. And I felt so comfortable with Penske. So I took my decision: I told Roger I was staying.”

Rick was leading Indy in 1981 when he came in for his second refuelling stop. “What followed was the scariest moment of my life. When you crash there’s no time to get scared: you’re busy, trying to lessen the consequences until you hit. But that day I was on fire for 32 seconds, which is a long time when you can’t breathe.

“I’m in the cockpit, hands on the wheel ready to go, when fuel sloshes over me. Then it all goes up. I’m struggling to release my belt, and I can feel the fire going up inside my helmet and down my throat, so I stop breathing. I jump out of the car, I’m trying to keep my eyes shut, I feel somebody’s hands on my neck, but then they go away because I’ve set that guy on fire too. You won’t believe this, but in 1981 fire marshals in the Indy pitlane didn’t have to wear fire suits. And methanol burns with an invisible flame, you can’t see it until the paint on the car starts burning and smoking. My dad was in the pit, he knew I was on fire because I don’t move that fast for anything. He grabbed a fire extinguisher and put me out.

“After I got my helmet off I put my hand up to my face, and my nose came off in my glove. Four of us went to hospital, because three of the crew were quite badly burned too. I was having my nose rebuilt and getting my eyelids to heal, so I missed the next race, and the gossips were saying I would retire. I thought, ‘I’m just getting started here’. The next race was on the big oval at Atlanta, four weeks after the fire and I was still all bandaged up, and we won that. I said, ‘How’s that for retirement?’ I won four more rounds that year, and took the Championship again.

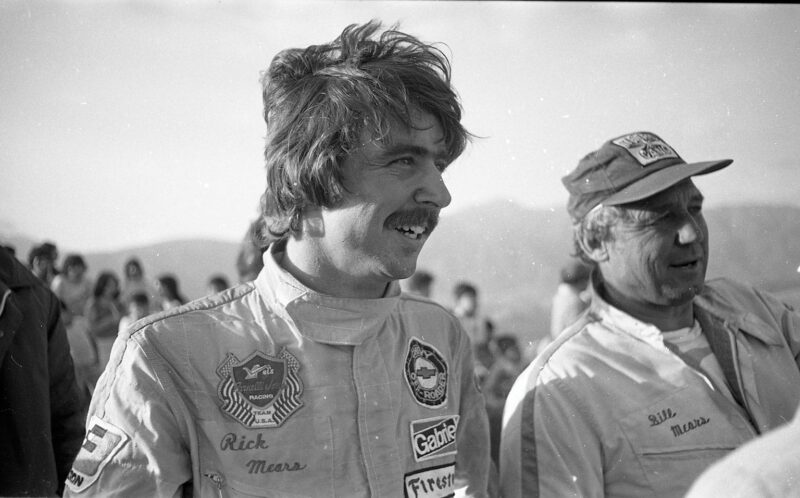

Moustachioed Rick at Baja Internacional in 1977

Motorsport Images

“I loved the high-speed ovals, they seemed to suit my style. On a speedway, smooth is the fastest way. The closer you can get to the limit on every lap and stay smooth, the higher your average will be. On road courses you have to get more animated, more physical. Being quick on the ovals is about experience, it doesn’t matter who you are. Finding the last one or two per cent takes seat time. When Fittipaldi came from F1 he got out of the car after his first try and said, ‘I’ve got a lot to learn.’ That’s when I knew he’d do well.

“I always liked the hands-on stuff, making changes to the car to make it run better. Today you pretty much do it all on screen, but back then we didn’t have computers, so the driver’s job was to be better than the next guy at making the car work. I’ve never liked driver aids. Your right foot should be your traction control, and your ABS. The more you take away from the driver, the fewer tools he has to beat the rest. It’s like a bumpy track. Take a bump away, you’re making it easier for everybody else. Leave the bump there, deal with it better than the other guy, there’s another advantage. Same in the race: you work out what changes you’ll need at the next stop, knowing a turn and a quarter on the front wing may solve a problem, but a turn and a half will be too much.”

In 1984 Rick had the worst accident of his career, on the Sanair tri-oval in Canada. Trying to get a clear lap in practice, he found himself squeezed between Bobby Rahal and Corrado Fabi, who was just leaving the pits. “I was keying myself off Bobby’s back wheel and I thought I’d be clear, but Fabi stood on it and the gap closed”. Rick’s car clipped Fabi’s, and he hit the wall. Typically, he blames himself. “In a race I might put myself in that situation and hope it worked out, but in practice it was just dumb.” In a huge impact the front of his March went below the bottom of the guardrail, tearing off the pedal box and the front bulkhead. Then, with his feet protruding, it rebounded, and smashed into the rail again. “After that I only remember bits and pieces. On the stretcher I was aware of Roger and my wife, and Roger shouting, ‘What’s my name? What’s my name?’ Then my feet, my feet killing me. I was screaming with the pain. They couldn’t give me pain killers yet because they didn’t know what other damage there was, they didn’t want to rattle my cage. Where my right foot should have been I saw a football, with five tennis balls attached to it. You have 28 bones in each of your feet. In my right foot every one was broken, or smashed. In my left about half of them were broken. My Achilles tendons were severed, too. The doctors said, ‘There’s nothing we can do with these feet, we’re going to have to amputate both’. Lucky for me Roger was there, and Steve Olvey, the CART medical director, and they said, ‘We’re not having that. We’ll take him somewhere else.’ Then I remember helicopter blades, like a scene from M *A *S*H, Penske’s private jet, ambulances, just bits and pieces.

On his way to victory in the 1973 Baja 500

“A few years earlier I’d have lost my feet, but Dr Terry Trammell at the Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis was at the cutting edge. He had the technology to deal with my smashed bones, using lots of pins and screws and wires. I was in hospital for over three months, I had a lot of operations, and then we had more issues with the heel. All the tissue was gone, you could see the screws holding the tendon. You can’t grow grass where there ain’t no dirt. Harry Buncke, a pioneering microsurgeon in San Francisco, worked on that using new techniques for tying blood vessels together.

“During all this I’d have one bad day, then two good days. But when I looked down and saw my feet were still there I said to myself, ‘Mears, you’re going to drive again’. My worry was, how long would it take me to get back to where I should be? Roger helped by stopping by to say, ‘How d’you feel about adding two more years to the contract?’ He told me not to rush things. After five months I was at Phoenix for a test. I couldn’t walk yet, so they lifted me out of my wheelchair, carried me to the car, and pushed me down into the cockpit. Simpson had made me a special pair of padded driving shoes.

I did a couple of installation laps, they checked the car, then I went out and leaned on it. Did 15 laps, came back in, all the guys clustered round, ‘How is it? How is it?’ I said, ‘It’s a little loose comin’ off of Turn Four’. They just fell about laughing. What they meant was, ‘How were my feet?’ But for the first time in five months I wasn’t thinking about my feet, I was thinking about the car.”

The following May Rick did the Indy 500, getting around the pits and paddock on a little electric buggy. He qualified 10th, and was running with the leaders when the gear linkage broke. Second time out, at Milwaukee, he finished third. He took pole for the Michigan 500, only for his transmission to fail. Then at Pocono, 11 months after the crash, he took pole — and won. “People had been saying I’d never be able to do it again, to the same level. That was a big monkey off my back.”

Mears and Penske first met 35 years ago and have been working together ever since

There were more wins, at Pocono again; at Indy for a third time; at Milwaukee, Phoenix and Laguna Seca. But the stand-out was his fourth Indy 500 win, in 1991. On the Friday before Pole Day, Rick’s rear suspension failed and his Penske PC20 destroyed itself against the wall. A return trip to the Methodist Hospital revealed that two bones were broken in his right foot. “Only Roger knew, I didn’t tell anybody else. My foot was hurting a lot when I moved it in the cockpit, either pushing down or lifting off, but I didn’t want anyone to have a reason to stop me running. The boys got the back up car ready, and changed the throttle springs and linkage to make the pedal as light as possible.”

And Rick took pole, his sixth at Indy, at a record 224.113mph. But mid-race he was slowed by bad understeer — and he was dealing with searing pain in his right foot. “I found that if I put my left foot on top of my right and pushed like that, it seemed to relieve the pain a little. And during the pitstops the crew tweaked the settings, so the handling came back.” Rick recovered to fight for the lead with Michael Andretti, and with 12 laps to go he executed a brilliant pass around the outside of Turn 1. “Not just because of the foot, but also dealing with the handling problems, that was my most satisfying Indianapolis win of all.”

At the 1992 Indy came another practice accident: a water pipe broke and sprayed water onto Rick’s rear wheels. The PC21 spun, cannoned into the wall and carried on down the track on its side. Rick had concussion, a sprained wrist — and a broken bone in his foot, the left one this time. The next day in the backup car he qualified ninth, two places ahead of team-mate Emerson Fittipaldi.

“But sliding along upside down, trying to catch my breath, with something — maybe fuel — leaking into the cockpit, I suddenly thought, ‘I don’t need this’. That was new: before I’d just have been thinking, ‘Is the back-up ready’? When I realised the liquid was water I relaxed, waited for them to get me out, but I couldn’t ignore that fleeting thought. Plus, the sprained wrist was actually a break. A few weeks later in the Michigan 500 the car went dead loose, and Michigan is a fast place, you don’t want to be loose there. It kept jumping out on me, and to catch it I was having to grab the wheel because I couldn’t roll my hand under. So I parked it. I had to pull out of the next few races to let the wrist heal, and one morning I woke up and I thought, ‘You idiot, what is wrong with you?’ If you’re wondering whether it’s past time, then it’s past time.”

At Penske’s end-of-season party, Rick quietly told the team he was stopping. It was just before his 41st birthday. “I never wanted to do a swansong year, a swansong race. I’m not superstitious, but at tests I’d always say to the guys, don’t tell me when it’s the last lap, just tell me when we’ve finished. Because it’s last laps when things happen. I was still competitive enough to win, but to me this whole sport is about going up. If you’re not going up you’re going down. And what made it much easier was that my relationship with Roger and the Penske guys carried on.”

As mentor and advisor, Rick continued to play a major role. He’s still doing so, 35 years on. Has there ever been a longer relationship between driver and team? “I go to all the Indycar races, and to a lot of the testing. Roger’ll ask me what I think of a driver, or he may talk to me before he signs someone. When a new signing is learning to communicate with his engineer, I can act as a sort of interpreter. It helps speed up the process. If it’s a younger kid, I’ll help him learn to work with the team.”

Rick divides his time between the Florida property he has lived in since the 1990s, close to the Atlantic Ocean, and a new lakeside house he has built in North Carolina to be close to his Penske responsibilities. For wheeled fun he has a 1933 Ford-based hot-rod with L53 Corvette power, and one remaining motorcycle. His feet still hurt, every day of his life; but he seems content, at peace within himself.

I know several perfectionists: they tend to be intense, obsessive people. Rick is the first relaxed, easy-going perfectionist I’ve met. It’s only when you pin him down, to try to identify where his speed came from, that you appreciate the quiet pressure he put on himself, constantly looking for improvement. He doesn’t dwell on his remarkable achievements: instead, he will think about how he could have done better.

“All the years I raced, I never felt I did the perfect lap. I had over 40 pole positions in Indycar, but none of those was perfect. I never ran a lap when I didn’t feel, ‘There’s some more there’. You get to a point, you refine it, you get a little more, you refine it again. I may have run a corner when I felt there was nothing more to come, but not a whole lap. I don’t care who you are, if you feel you’ve run a perfect lap, you’re not telling yourself the truth. I always thought, ‘If I ever do a perfect lap, I’ll quit’.”

An exceptional man: and, above all, a modest one.