No argument about that. Piquet was never the fittest of drivers, after all, and Reutemann looked to be in one of his unbeatable moods. In qualifying at Monza he’d produced what Villeneuve rightly called ‘the lap of the season’, setting second-fastest time in his Williams-Cosworth, and splitting the turbocharged Renaults of René Arnoux and Alain Prost. And now, in very different surroundings, came another scintillating lap: set on the first day, it would remain unbeaten. Everything pointed to one of those Reutemann weekends, when the rest were wasting their time, and most onlookers were hoping it would turn out that way.

Some, like Jones, weren’t bothered either way. If Alan loathed Piquet, he had no time for Reutemann either, and would not be volunteering to ‘help’ his team-mate. Which of the two, I asked, did he hope would take the title? “Neither…”

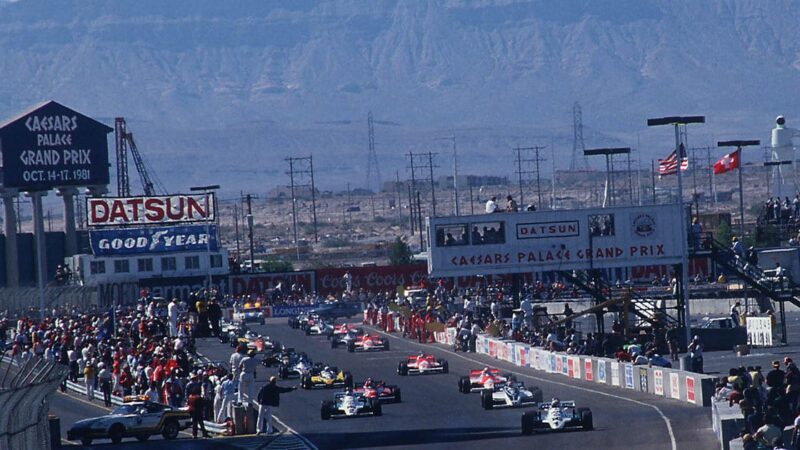

Even then Max Mosley was saying spectators didn’t count for much any more, that the future success of F1 lay in television coverage, and the Caesars Palace GP brought that home. It was like being at the filming of a TV special, rather than the settling of a World Championship, and for those in the grandstands it was a dead loss.

The race gets underway

DPPI

Some indication of the lack of interest in, not to say knowledge of, F1 was gleaned in the betting shops, only a few of which offered odds on the race. I ventured into one, and after perusing the chalk-written board and disregarding the likes of Peron, Grabbiani, Munsell, Stohr (who wasn’t even racing) and Cheevers, I went with Jones, offered at 4/1.

Although Alan, the reigning champion, had had poor luck through 1981, he had driven even better than in his title year, and I had a feeling he was going to walk his last race. Actress Susan George, a Williams guest for the weekend, strengthened my resolve when she told me she’d never seen Jones lose a GP. I could hardly resist advice like that – and, as it turned out, my winnings compensated in part for the hundred dollar bills removed from my pocket earlier in the week.

Had I bet on the championship outcome, my money would have been on Reutemann. He was on pole, followed by Jones and Villeneuve, and although Piquet was in fourth he had looked perilously frail in practice, while it seemed that Laffite, only 12th, could be discounted.

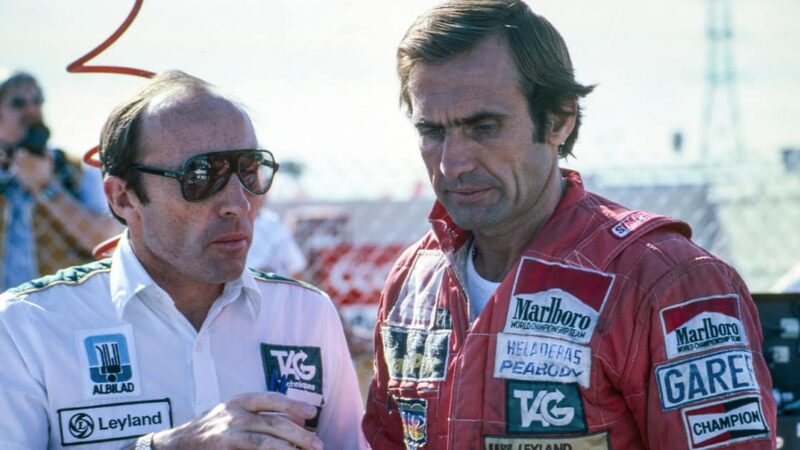

As well as that, there was Reutemann’s demeanour in the build-up to the race. Given the pressure of the championship one might have expected him to be even more reclusive than usual, but in practice Carlos behaved like a man who knew he had the title in the bag. The three title contenders appeared on a TV chat show the night before the race, and he ruled proceedings. The tension was in the faces of Piquet and Laffite.

Reutemann (with team boss Frank Williams) in typically reflective mood pre-race

DPPI

Carlos apart, the outstanding performance in qualifying had come – predictably – from Villeneuve, who, as at Monaco earlier that year, had wrestled his unwieldy Ferrari 126CK into third on the grid, en route achieving angles extravagant even by Gilles’s normal standards.

“You put on new tyres,” he said, “and it’s OK for four laps – after that, forget it. It’s just like a fast, red Cadillac, but it flexes so much that it’s incredibly forgiving. I can get so sideways I’m almost looking over the rollover bar – and still it comes back! Mind you, I’d sooner have it vicious, with some grip…”

In the paddock there was general delight that Derek Warwick, after a nightmare debut season, had qualified his recalcitrant Toleman-Hart.

“When I found Derek Warwick after the session, he looked like a man on pole”

When I found Derek after the session, he looked like a man on pole: “It’s so long since I’ve raced I’m worried about my fitness – particularly at a place like this. I’ll just do the best I can…

“Whatever happens I stand to make some money out of this. At mid-season Jackie Oliver bet me I wouldn’t qualify the Toleman at any race this year. ‘All right,’ I said, ‘how much?’ ‘Whatever you like,’ he said, ‘a thousand, 10, 25…’ So we settled on 25 grand – and there was a witness! You can keep your betting shops…”

It was as well that Warwick’s wager hadn’t required him to finish a race in 1981, for the Toleman retired with gearbox problems, one of 13 cars which failed to make the flag. How easy it is now to forget that cast-iron reliability wasn’t always the way of it in F1.