Lunch with... David Hobbs

The results didn't always come his way, but over three decades this expat Brit enjoyed the sort of variety in his racing career that today's F1 stars can only dream about.

Beckermedia.com

David Hobbs is 71 now, still the quintessential Englishman with the deadpan humour that stayed with him through a 30-year-plus racing career. By his own assessment, misfortune and missed opportunities meant he never reached his potential as a driver. Others take a different view, seeing a versatile professional who could be relied upon to be determined, intelligent and quick in anything. Certainly, few have raced so many different types of car, from F1 to NASCAR, from Formula Junior to Indy, from 20 starts at Le Mans to championship titles in Formula A and Trans-Am. All this from a man whose first racing car was a Morris Oxford automatic.

For over 20 years David has lived in the USA, where his enduring second career as a TV commentator has made him more famous than he ever was in his racing days. His witty, shrewd coverage of Formula 1 for Speed Channel has earned him a fan base that crosses generations, especially when his plummy English tones lapse into a politically incorrect Deep South accent. US schoolkids like to imitate one of his catchphrases: “He done blowed up.” In his adopted hometown of Milwaukee he runs a thriving Honda dealership with his sons Greg and Guy, and lives in a fine, rather English house overlooking Lake Michigan.

It’s a long way from a wartime childhood in Leamington Spa, where his father Howard pursued a lifetime’s dream to develop an efficient and compact automatic gearbox. “He made prototypes for everybody: BMC, Armstrong Siddeley, Fiat, BMW. In the end Daimler took it up for their new small car, the Lanchester Sprite, but that never went into production. Borgward were going to use it, but they went out of business too. Dad had a life of absolute disappointment. He used to say, ‘Look at Rudolf Diesel. Nobody realised how brilliant his engine was, and in the end he drowned himself. Now diesels are everywhere.’ Autos were big and slushy then, but Dad’s was small and light, and very advanced for its time. Today’s transmissions use a lot of the same thinking.

“My academic record at school is best left buried, but I was always fascinated by cars, so I joined Daimler as a teenage apprentice.

My mother’s shopping car was an old side-valve Morris Oxford, fitted with one of Dad’s gearboxes. In 1959, when I was 19, I entered it for a race at Snetterton. The scrutineers said the gearbox wasn’t homologated, so I had to run as a GT against the Lotus Elites and AC Aces. I lurched around at the back until, at peak revs on the Norwich Straight, the engine exploded. In Dad’s shop there was an MGB engine he’d got from BMC to use for trials, so we put that in. Off I went to Goodwood to get another signature, and that blew up too.

“As his everyday car Dad had an XK140 drophead, fitted of course with a Hobbs box. After the disasters with the Morris I pleaded and whined to be allowed to race it, and finally he relented. I went to Oulton Park with the car just as it was, on Michelin X tyres, put it on the second row, and on the last lap hit the bank and turned over. I phoned home and Dad said, ‘I know. I saw it on TV. You broke it, you fix it.’ Margaret and I — we were already an item then, and we’re still married 50 years later — we clambered into the wreck and set off for home. On the way the mangled bonnet came open and flew over the roof. I got a little man in a shed near Daventry to straighten it all out, but he must have painted it on a damp day, because it always looked rather matt after that.

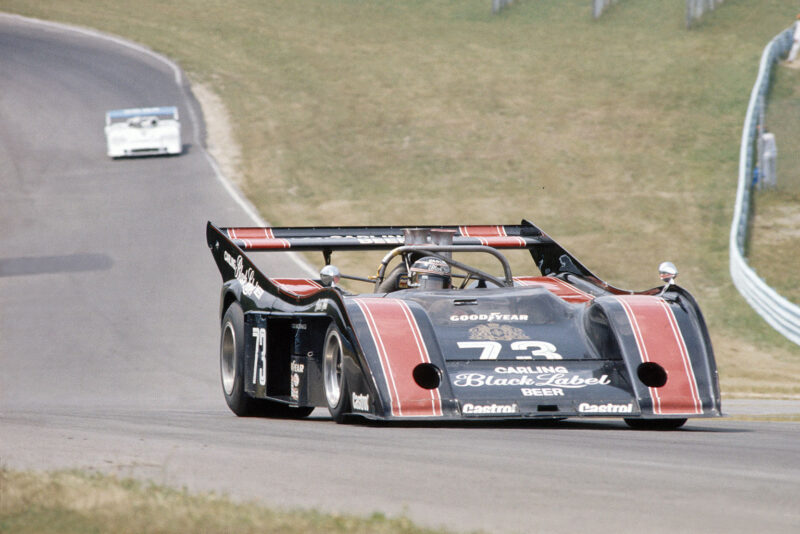

Hobbs split winner Donohue and Scheckter in 1973 Can-Am race at Watkins Glen

Motorsport Images

“I was now a Jaguar apprentice, because they’d taken over Daimler, and I purloined a few bits for the XK140: disc brakes, bigger SU carbs. I was sliding and oppositelocking all over the place, no idea about spring rates or anti-roll bars, but I won several races that year. The XK looked pretty dreadful by now — various dents and wounds, torn hood, only one headlamp because I’d made the other into a carburettor scoop. On the grid at Silverstone [Jaguar competitions boss] Lofty England looked down from his great height and said, ‘Smart turn-out, Hobbs.’ That deflated me a bit, but in the race I had a terrific dice with an Aston DB4GT, and I beat it. Afterwards Lofty said, ‘I must admit, Hobbs, you do race as if you mean it.’

“Jaguar had just built E2A, the missing link between the D-type and the E-type, for Cunningham to run at Le Mans in 1960. I’m still an apprentice, Lofty summons me, and there’s Bill Heynes, Wally Hassan, Mike Parkes too, we all go off to Silverstone with E2A and unload beside Abbey Curve. I’d never driven anything as serious as this, and after a few laps coming into Abbey, a corner I never did like much, I drop the lot. After a horrendous slide I come to a halt in a cloud of rubber smoke, right in front of everybody. All four tyres were flatspotted, so they put it on the trailer and took it away. End of Jaguar works drive.

“Ford were now proposing to make the Hobbs box an option on Anglias and Cortinas, so it looked like we’d hit the big time. I persuaded Dad we should show the world how well the box worked by racing it. So we bought a Lotus Elite over the winter of 1960/61 and prepared it very carefully. By about May we’d found our pace, and after that we were almost never beaten. Jim Hall gets the credit for the first successful automatic race car, but he came a long time after us. I went to the Niirburgring 1000Kms with Bill Pinckney as my co-driver, and Les Leston protested us because our gearbox was non-standard. So we ran with the 1600cc sports cars, beat the Porsches and won that class anyway.

“Colin Chapman got very interested, and asked to borrow the Elite for Jimmy Clark to drive at Daytona. Lofty England fixed me up for the same race with an E-type belonging to a Hertfordshire chicken farmer called Peter Berry. My first professional drive, and my first trip to America. I was 21. I’d never met Jimmy before, but of course he was a hero to me. We flew to New York and drove flat out down through Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia and into Florida. We were stopped a dozen times by the cops with their guns and their pressed shirts: ‘Outa the car, put ya hands on the roof!’ Jimmy was rather nonplussed by the whole thing. At Daytona we were introduced to Bill France Sr, Jimmy as the Formula 1 World Champion, which wasn’t true yet but soon would be, and me as the British Touring Car Champion, which certainly wasn’t true: the only saloon I’d ever raced was the Morris. In the race the E-type’s fuel pump went — Peter Berry’s cars weren’t exactly honed to perfection — but Jimmy led his class by miles in my Elite until he couldn’t restart it after a pitstop. The starter had been fried by the exhaust, and the one thing you couldn’t do with the Hobbs box was push-start it.

“Back in the UK I raced Berry’s Jaguar 3.8 and his E-type, and then Team Elite offered me a ride at Le Mans with Frank Gardner. I’d never met Frank before, and he was wonderful: the absolute ace at one-liners. I loved Le Mans from the first. In the little Elite you spent most of your time watching the rear-view mirror, but we finished eighth overall, won the class and the Index of Thermal Efficiency. I did the Niirburgring 1000Kms again in my Elite, taking as my co-driver a fellow Jaguar apprentice called Richard Attwood. We were leading our class when something broke. In return Atty let me drive his Formula Junior Cooper at Oulton Park. It was my first singleseater race, it was raining, and everybody warned me I’d find it difficult to adapt, but I won by 13sec and set fastest lap.

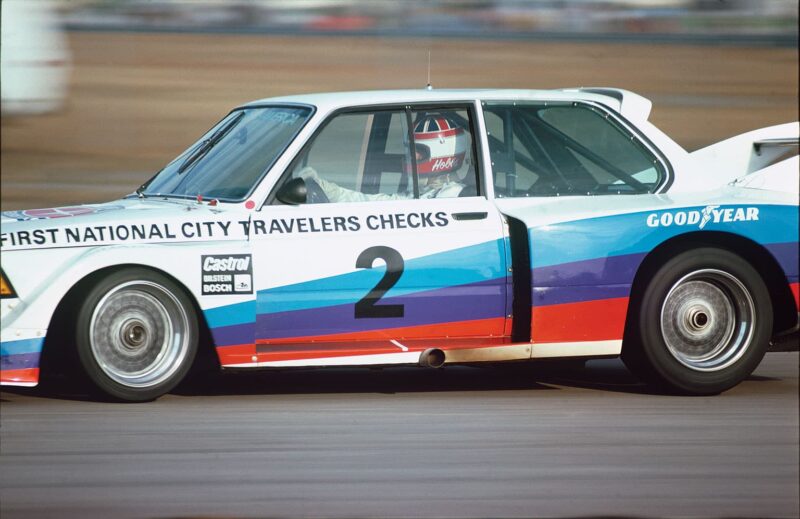

BMW 320I was shared with Peterson and Sam Posey at Daytona in 1977

Motorsport Images

“On the strength of that I was offered a Midlands Racing Partnership Formula Junior Lola for 1963 alongside Attwood and Bill Bradley. I crashed a couple of times, which upset them, but at the May Silverstone I had a good race with Denny Hulme in the works Brabham. We swapped the lead between us, and then my gearlever snapped off. On the last lap I broke the lap record trying to catch Denny, changing gear with the stub, but he beat me by a length. At Le Mans Richard and I drove the Mk6 Lola, the forerunner to the GT40, and I crashed it. The gear selection was getting progressively worse and finally on Sunday morning I arrived at the Esses in neutral. I spun and hit the wall, and that was us done.

“I took the Elite and the FJ Lola, towing a double-deck trailer behind my Ford Zephyr, down to Clermont-Ferrand, that wonderful road circuit in the Auvergne mountains. Going through the long, fast uphill left-hander in practice, Paul Hawkins came past in one of Ian Walker’s yellow Lotus 23s — and coming down the hill towards us was a Simca 1000 with four French farmers in it, chatting away and smoking their Gauloises on their way to market. Somehow we both missed it, and back in the pits we gibbered at each other: ‘Did you see what I just saw?’ I later crashed the Elite, but I ran near the front in the FJ race until my fuel pump went on the blink.

“Then Ford changed their minds about offering the Hobbs transmission on their small cars. That was when Dad’s firm went belly-up. I’d been working for him for £20 a week, and my Formula Junior racing plus the Lola at Le Mans had earned me about £900. Margaret and I were living in a little house in Warwick, one son already and one on the way. We had a summit conference, and decided I should have a go at earning a living as a racing driver. Small snag: what was I going to drive? MRP, in their wisdom, had dropped me in favour of Tony Maggs, so I went to Selwyn Hayward at Merlyn and offered my services. He paid me £25 a race to drive his 1-litre F2 car. I also drove a works Lotus-Cortina alongside Mike Spence: won at Roskilde in Denmark, and raced it at Road America and Marlboro. I really wanted an F2 drive for the Ron Harris Team, and I got my wish at AVUS: two long straights, wall-of-death banking at one end, tight hairpin at the other. On lap one I ran into the back of my team-mate Peter Procter at the hairpin, suspension bent, out. I got another chance two years later at Reims. Lap one, going into the Thillois Hairpin, Pedro Rodriguez missed a gear, almost stopped dead. Ran into the back of him, suspension bent, out. No more Ron Harris drives.

“In 1964 I did Le Mans in a works Triumph Spitfire with Rob Slotemaker. It would only do about 120 top whack, flat all the way from Arnage to the Esses, teetering through Tertre Rouge with its rear swing-axles on tip-toe. We won the class and I was paid £200, which was good money. In 1965 I drove for them again, but Rob crashed it. I did some F2 races for Tim Parnell, and Tim offered me my first F1 drive in the French Grand Prix, in a lovely little BRM V8-engined Lotus 25. On the way down a laundry van turned across me. Broken arm, jaw, nose and cheekbones, three weeks in hospital. I never hurt myself that badly in a racing car.

“That year I also got myself into a Lola T70. The car was run by David Fletcher and entered by his little garage at Long Melford, Harold Young Ltd, although it actually belonged to an Essex farmer called Ian Yates.” Ensconced in something big and hairy, David began to attract attention. At the Easter Monday Goodwood he finished third to Jim Clark and Bruce McLaren, and two weeks later came the TT at Oulton Park. David’s average speed for the two heats was the fastest, but a muddle with the chequered flag at the end of the second heat gave Denny Hulme’s Brabham BT8 an extra lap and he was declared the winner. “Eric Broadley went straight to the stewards, and they said he was absolutely right, but it was too late to change the result. It would have been the T70’s first big win.” That came a few weeks later, when David won the Guards Trophy at Mallory Park.

At the Nurburgring in 1967 aboard F2 Lola T100

Motorsport Images

“Then we made a brave foray, on a tight budget, to North America to do what became the Can-Am Series. I’d got really friendly with David Fletcher by now, but when we went out he would never drink, said it made him ill. What I didn’t know was that he was a recovering alcoholic. And in Canada, away from his wife, he hit the bottle. We went to St Jovite, where I ran second to John Surtees but dropped to third after a pitstop, and Mosport, where Surtees was badly injured in that enormous accident. From Toronto we had to get to our next race in Seattle, 2000 miles away, and had no idea how to do it. Up pops this spivvy little guy with voluptuous girlfriend and voluptuous Cadillac. He was just a race fan, but we tied our trailer to the back of the Cadillac, put the spare wheels on the roof, round the top of Lake Superior, across Canada to Winnipeg, then Moose Jaw and down to Seattle. Did the race there, then Cadillac guy and his heavily endowed girl take us another 1000 miles down to California and Laguna Seca, and then Riverside. All the time David was getting steadily worse, and was now constantly inebriated. So we put him on a plane home, and said to the airline, ‘Whatever you do, don’t give this man a drink.’ That was the last time I saw him. He was dead by March.

“For 1966 I raced a Team Surtees Lola T70, and did a lot of the testing. Eric Broadley’d be there with his clipboard and pencil, and you’d come in and say, ‘It’s understeering through Copse and Becketts, Eric.’ ‘Is it? It shouldn’t be doing that. Try it again.’ So you’d go out again, come back in, ‘It’s still understeering, Eric.’ Is it really? It shouldn’t do that, you know.’ At a Mallory test I had my first lesson in aero. I was doing 46sec, understeering like mad around Gerards, then Eric gets out a couple of little strips of aluminium and says, ‘We’re going to try these.’ The mechanic, Malcolm Malone, fag permanently stuck in the gap in his teeth, lines them up on the nose with Eric saying, ‘Up a bit, down a bit’ and then pop-rivets them on. I couldn’t see how these little pieces could possibly make any difference, but I go out and at once I’m a second and a half quicker. I come in and say, ‘It’s a miracle, the understeer’s gone — in fact it’s oversteering now.”Oh, we can fix that,’ says Eric, and Malcolm starts popriveting strips on the back. Today everybody spends millions on wind tunnels, but in those days it was Eric saying, ‘Up a bit, down a bit.’

“I drove an F2 MRP Lola at Barcelona in the pouring rain, finished fourth behind Brabham, Stewart and Hulme and ahead of G Hill. And I finally got my Tim Parnell F1 drive, in the nonchampionship Syracuse Grand Prix. By the end of the race the spectators were all over the road, and on the slowing-down lap I was driving over their feet. It was a thin field, but I finished third behind the works Ferraris of John Surtees and Lorenzo Bandini. Afterwards Tim said, ‘Bloody ‘ell, Dave, I thought you’d ‘ave done better than that.’ There’s no pleasing some people. “Bernard White, Lord Hanson’s brother, asked me to drive his GT40 in the Springbok Series, sharing with Mike Hailwood. I didn’t know much about Hailwood and I didn’t like the idea at all. Apparently Mike felt the same: ‘Hobbs? Don’t want to go with him, he’s just a public school poof.’ But as soon as we met each other we really hit it off. After the Kyalami Nine Hours we went across the desert to Cape Town and did the Three Hours there. I came in to hand over to Mike, the mechanic didn’t shut the fuel flap properly, and when Mike slowed for the first corner fuel sloshed all over the brakes and it caught fire. We went all the way to Bulawayo and won there, and over Christmas we won at Pietermaritzburg as well.

Everything with Mike was always a terrific romp. He liked the ladies, never seemed to eat breakfast and dinner with the same girl. “I drove Bernard’s little 2-litre BRM in the British Grand Prix at Silverstone, put it on the fourth row of the 4-3-4 grid and finished eighth. So he sent it to Mosport for the Canadian GP. I qualified 12th and ran eighth in the wet early stages. Then it dried out, but I still finished ninth. But I spent most of 1967 trying to make the Aston Martin-powered T70 work. It was nothing like as strong as the old pushrod Chevy. At the same time Lofty asked me to test the XJ13 Jaguar at MIRA. They were thinking of getting back into racing. Sir William [Lyons] came along, and their aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer. The XJ13 was antiquated — terrible gearbox, bad brakes, narrow wheels on ancient Dunlops. But the four-cam V12 was beautiful, smooth as silk, massive torque. They could have done a lot with that.

Subbing for Hailwood in McLaren M23 at Monza in 1974

Motorsport Images

“Le Mans with the Lola-Aston was a disaster. John Surtees went to a different make of spark plug just before the race, and had a massive row with the Aston people about it. Three laps in, it burned a piston. A fortnight later, for the Reims 12 Hours, we were back on Chevy engines. John started, and after an hour and a half I was togged up and ready to take over, but he waved me away and went back out. Then the crank broke. Five weeks after that we were at Brands for the BOAC 500 and started from the middle of the front row. John led the first lap, but stopped on lap two to adjust the fuel pressure. Over the next five hours we sweated our way back up the field: then a piston went.

“But every cloud has a silver lining, because my drives in the Lola got me into John Wyer’s team of Gulf GT4Os for 1968, paired with Paul Hawkins. Jacky Ickx and Brian Redman were in the other car. It was a great set-up. Grady Davis of Gulf and John Wyer were a wonderful couple of old codgers — Wyer liked his martinis vay vay dray, just pass the bottle over the glass — and David Yorke was team manager, John Horsman chief engineer. The only problem was that David Yorke was in love with Jacky Ickx, a bit like Helmut Marko and Sebastian Vettel today, and Ickx could do no wrong. Not that he ever did much wrong, of course: he was always incredibly fast. But it used to infuriate Hawkins to see him wrap Yorke around his little finger.

“The GT40 was wonderfully comfortable for long races: enough room inside, pedals just right for heel-and-toe, that lovely ZF box, plenty of torque, predictable handling and no vices. At Daytona, after 15 hours, Paul and I were swapping the lead with the Siffert/Herrmann Porsche when a tiny bit of welding wire wore a hole in the fuel tank bag. At Sebring we were leading again when Paul had the incident with the Dutch girl.” A Porsche 911 had to swerve to avoid Liane Engeman’s very slow Javelin, and Hawkins hit the 911. His colourful Australian comments about women drivers made headlines around the world.

Next time out for JW, the Hobbo/Hawkeye pairing won the Monza 1000Kms. “I think it was the last time they used the whole of the old circuit, including the banked oval, which was so rough the car was banging about all over the place. We were fourth at Spa — Jacky walked that, of course, in the pouring rain — and then we went to Watkins Glen for the Six Hours. By the end of the race Paul and I had a full lap lead over Ickx/Lucien Bianchi in the other car, and everybody else was miles behind, so we were stroking to the finish. Suddenly Yorke gave me the EZ sign, because he wanted Ickx to win. I wasn’t at all amused. I did as I was told and let the little Belgian past, but I had a row with David in the hotel afterwards, because there were no driver points involved, and JW got maximum points for their 1-2 anyway. The Gulf guys didn’t like it much either: at the airport next morning one of them slipped Paul and me $1000 each.

McLaren M20 from 1973 Watkins Glen race

Motorsport Images

“For 1969 my mate Hailwood replaced Hawkins as my JW co-driver, and we were leading at Daytona when the block cracked. At Le Mans Mike and I were going right along, and during the night I’m following two Porsche 908s into the Mulsanne kink when suddenly there’s a flash of orange flame, headlights pointing skywards, the road’s filled with smoke and debris. I burst through the smoke and there’s half a Porsche stuck in the guardrail, burning merrily. Cartwheeling in front of me is the other half, and as I watch the driver pops out of it and goes bouncing down the road. I managed to miss them both, came in and said to Mike, ‘We’re going to be under a caution for ages, a chap’s just been killed down at the kink.’ But it was Udo Schatz, who was a bit overweight, and old Udo just bounced. Never had a mark.

“On my next stint, down to Mulsanne Corner from 200mph, the brake pedal goes straight to the floor. Down the escape road, quick U-turn, come in: ‘We’ve got a major brake problem.’ David Yorke says, ‘It’s the pads.’ I say, ‘It’s not the pads, it happened suddenly.’ He says, ‘You’re the driver, leave the mechanicals to me.’ So they change the pads, off I go, end of the pitlane I try the brakes, pedal to the floor, nearly run down a marshal. Round again, in again, they find a caliper pipe has been chopped by a wheel balance weight. By the time they’d replaced it and bled the system we’d lost an age, and we finished third. Without that, John Horsman says to this day we would have won, and the famous battle to the line between Ickx and Herrmann would have been for second place.

“Then Wyer did his deal with Porsche to run the 917. So in November Dr Piech, Dr Bott, Herr Falk, Herr Flegl, all the Porsche heavies were assembled at Daytona to watch a JW test. Going onto the banking, up the gears from second to third, I managed to put it into first instead, and blew the engine. The heavies were not amused. Gear selection on the early cars was abysmal, and it turned out that everybody missed gears — including Jo Siffert, who did it in front of the pits when he was leading Le Mans. But Dr Piech took against me for that, so I was fired and they hired Leo Kinnunen. Except Wyer ran a third 917 at Le Mans, and they brought Hailwood and me back to drive it. Siffert missed his shift, the Rodriguez car blew its engine, the Elford car did its electrics, so we were looking good. But it was another one I didn’t win. When it started to rain Mike, still on dry tyres, crashed. Wyer was absolutely furious: ‘Don’t ring us, Hailwood, we’ll ring you.’

In 1974 Indy he took McLaren-Offy to fifth

Motorsport Images

*

On the F1 front, while John Surtees was with Honda in 1967, the aircooled V8 had killed Jo Schlesser in its first race at Rouen. But Honda wanted to persevere with it, so John asked me to test it at Silverstone. It was terrible: very fragile, very peaky, and it had this dreadful whippy chassis. If you put stiffer springs on it, it just twisted the chassis more. But I also tested the Lola-chassis V12, and got under Chris Amon’s Ferrari lap record, which really chuffed me. They had two V12s ready for the Italian GP at Monza, and I got the drive. I was in sixth place with 25 laps to go when the engine dropped a valve. A full two-car Fl season was planned for 1969, with me in the second car, but Honda chose that moment to withdraw.

“So John built an F5000 car, and in the British series I scored the first win for a Surtees chassis, at Mondello. Then he sent me to America to do Formula A. I’d missed the first five rounds, but I won at Donnybrooke, St Jovite and Thompson, and then the final at Sebring. I was a bit lucky, because Mario Andretti’s Lotus 70 blew its engine when he was leading me, but I missed the championship by one point.”

*

The US races brought David into contact with Mark Donohue and his mentor Roger Penske. “Penske said, ‘Haabbs, come drive for me. I’m running a Ferrari 512 in sports cars, and I want you to do Indy too. If you want to do Formula A, that’s fine, but not for Surtees because he’s Firestone and we’re Goodyear. I’ll talk to Carl Hogan, you can do it for him.’

Hobbo/Hailwood Ford GT40 was third at Le Mans in 1969

Motorsport Images

“So I did the 1971 FA championship in Hogan’s McLaren, won five of the eight rounds, won the title. I went on to drive for Carl for five seasons. Meanwhile Penske brings to Daytona this incredible blue Ferrari. Works Ferraris were kind of tatty in those days, lumps of weld everywhere, but you could eat your dinner off this. It had been completely stripped and rebuilt, trick refuelling kit, Traco had done the engine. David Yorke almost had a seizure when he saw it. We start from pole and lead the race, then around midnight Elford’s 917 has a puncture on the banking. Lots of dust and smoke, Mark slows for the yellows and is hit by a 911. They spent an hour sticking the 512 together with tank tape, and we still finished third. Sebring, we’re on pole again, and mid-race Mark and Pedro get into a barging match. Mending that damage lost us ages, and we finished sixth. At Le Mans we were running third on Saturday evening, and the engine blew. Last outing was Watkins Glen, and I never got in the car: Mark was leading from pole and the steering broke.

“Mark was very good both as driver and engineer. Bit of a loner, introspective, felt he had to be with the guys all the time: drive the truck, sweep the floor, show them he wasn’t just a driver. He was from Irish stock and didn’t like the English, but he used to say, ‘For an Englishman you’re not a bad guy.’ Some of the things he did I wasn’t keen on: like he put a locked diff on the Ferrari, so you had to alter your driving technique in slow corners, chuck it in and get the rear to slide, or it just understeered. The first time I drove it I said, ‘What the hell is wrong with this car?’, but he said, ‘That’s how it’s supposed to be. Get used to it.’ So I adapted.

Father’s XK140 came a cropper at Oulton Park

Motorsport Images

“Indy was something else again. It’s not like the usual American oval, because the banking is so flat and the corners are so fast — more like four very quick bits of Spa tied together. You could see why road racers went well there. We were lapping in the 170mph bracket then, but doing 225 on the straights, so you braked for the corners. With the huge turbochargers the throttle lag was terrible, so you’d try to keep the throttle open while you were braking with your left foot. I was in Mark’s old Lola-Ford from the year before, qualified it mid-grid and everything was going fine. Around half-distance I was in Turn 4, just ahead of Rick Muther in the Sugar Ripe Prune Special, when there was this terrific clattering banging noise and the engine stops. I look in my mirror, Where the hell’s Rick gone? He’s done a huge swerve trying to miss me, hits the wall, comes booming in from 7 o’clock, hits me, spins me round, he’s up on two wheels, I hit the wall too. When it all stops I jump out, visor covered in oil, blunder towards the fence and nearly get run over by A J Foyt. My first Indy.”

By now David was earning a good living, taking drives in USAC, Can-Am, Trans-Am, F5000 and even the Tasman Series. In Europe he did Le Mans for Matra, and a couple of Grands Prix for Yardley McLaren when Mike Hailwood was injured. “My best Can-Am race came in 1973, with Roy Woods’ McLaren M20. By then all the quick boys had the Porsche 917 turbos, but at Watkins Glen I got second, splitting the 917s of Mark Donohue and Jody Scheckter. One of my better days. At Indy that year I was in Roy’s Eagle-Offy, only qualified 22nd but I worked my way up, passed a lot of the quick guys, and I was seventh when the engine stopped. I freewheeled into the pits and they had a poke around and decided the magneto drive had sheared. They put in another one, it fired up, and I finished 11th. For 1974 I had a McLaren-Offy, qualified ninth and finished fifth that time.”

Hobbs also raced Lola T310 in Can-Am

Motorsport Images

There was the big Broadspeed Jaguar XJ12C — “a complete disaster, but Ralph Broad was such a character” — plus three seasons of IMSA in a McLarenrun BMW 320. “About 670bhp, but huge turbo lag. BMW were gathering information on racing turbos, ready to do Fl with a turbo four a few years later. In some longer races Ronnie Peterson shared with me. A very nice man. Never wanted to change the car: ‘Hey Hobby, it’s your car, set it up how you like it, I’ll drive it like that.’ Then he’d be faster than me anyway. It wasn’t always reliable, but in 19791 won the Road America 500 sharing with Derek Bell, beat all the Porsche 935s.”

NASCAR too, running as Benny Parsons’ team-mate in the Daytona 500: “Coming off Turn 4 on the first lap, in a pack of 42 cars, half of them scraping down the wall, concrete dust, rubber smoke, I thought, ‘Do I want to be doing this?’ But I managed to get into the top 12 when the rear rollbar broke and I nailed the wall. Then I did the Michigan 400 for Junie Donlavy. I’m going like Jack the Bear, running near the front behind Darrell Waltrip and Cale Yarborough, and I lose it coming off Turn 4. Spin 720 degrees and end up pointing down the pitlane, so I motor in for fresh tyres. Old Junie leans in the window and says, ‘That thar was the finest drivin’ I ever seen.’ He didn’t realise it was pure luck. It was August, hot as hell, I was like a melted pack of butter, but they said, ‘Keep goin’, boy, you’re doin’ great.’ I did finish, in about 17th place. My last NASCAR race.

In Surtees F5000 at Oulton Park in 1969

Motorsport Images

“In 1983 I was hired to drive in the Trans-Am Series in a two-car team of Camaros with Willy T Ribbs, $6000 a race plus a share of the prize money. I won the title, he came second. I was also running with John Fitzpatrick in Porsches: third at Le Mans again, and fourth twice. Fitz was backed by J David, real name Jerry Dominelli, who seemed to be a financial genius, investing clients’ money in foreign exchanges and spending money like a one-armed paper-hanger in a gale. In fact he was a conman, but we didn’t know that. He was very convincing, paid us well, and kept the 935s and 956s coming. When I sold a BMW dealership I had in Houston I invested the money with him, and this was about six weeks before the whole house of cards collapsed. He was jailed for 10 years. I did manage to get my cash back in the end.

“In 1990 I was at Dijon in a Joest 962 with Jonathan Palmer. I’d done very little racing that year and wasn’t fit enough. It’s all big swooping right-handers there, and after three laps of practice I couldn’t hold my head up. I went to a pet shop and bought a dog lead, hooked it up to my helmet to support my neck. We finished eighth. But I knew that, after 32 seasons, it was time to stop.

Lotus Elite had Hobbs Mechamatic gearbox

Motorsport Images

“All those cars and races, all those incidents, for some reason I never hurt myself. That’s why, today, I don’t do historic racing seriously. I’m not superstitious, but you can’t go rushing around at 170mph all your life and not expect to get hurt eventually.” But at the last Goodwood Revival David did accept a guest drive in a small saloon. He likes the irony: he started in a Morris Oxford and he’s come round to an Austin A40. With rather a lot in between.

Hobbs in Jaguar 3.8 at Goodwood Easter meting, 1962

Motorsport Images