He was definitely in the minority, even at that point Michelin had become so disenchanted with the test miles denied it by Renault unreliability that it had switched its main effort to Ferrari.

Castaing, the original technical director of the project, left during the ’79-80 off-season. Some insight into the intensity of the experience is revealed as he explains why. “Being under the microscope with all the pressure of representing a big company like Renault was very tough. Also, motor racing is such a narrow, focused world. Although it’s good to be focused, at some point it keeps your mind from growing. I told Larrousse that I wanted us to try to win the world championship in 1980 and then was going to do something else.

“I thought winning the title in 1980 was realistic. But I was having arguments in private with Larrousse. We already had Prost under contract and we could have had him replace Jabouille for ’80. I was arguing that keeping Jean-Pierre was attaching a weight to our foot because, although he was adding value, he was not a potential champion in any sense. Larrousse was saying, ‘No, we have time to do that later’, and I became frustrated. I was not convinced he saw the window of opportunity we had. If we didn’t win in 1980, it would be much more difficult when everyone else had their own turbos and our advantage evaporated. I sat down with the senior people at Renault and told them I wanted out; they wanted people for a new project in America. We packed and went that same day.”

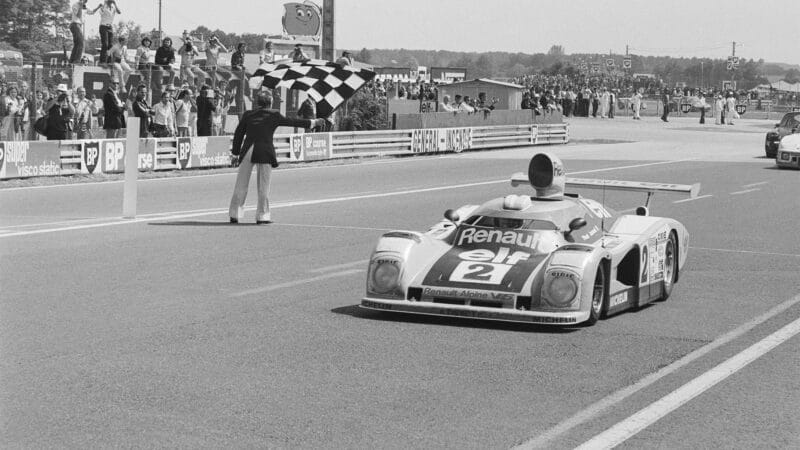

Renault won just three races in 1980 and finished 82 points shy of the constructors’ crown

Grand Prix Photo

Of course the title didn’t come in 1980 and not in the Prost years of ’81-83. The window of opportunity Castaing had spoken of was well and truly closed thereafter as the British teams found turbo engines of their own but only after a core of them had tried to have the whole concept banned from F1. When that initiative failed, the Brits got their heads down and beat the Renaults through engine parity and superior chassis technology.

“The engine was always the main asset,” says Migeot. “We lacked a chassis culture. There were a lot of good people but we weren’t properly equipped. Renault in those days would never have committed to a moving-ground wind tunnel and that’s what was required.”

The intervening years, before the Brits caught up, were lost to poor reliability. Only part of this was down to pioneering the turbo route, as Migeot explains: “In 1982, for example, we lost about eight races for the sake of an electric motor that cost 100 francs. That was because the electronics department was one man, doing everything from electric plugs to the sensors on the fuel injection, and he couldn’t cope. The next year the pieces for the new motor cost 100 times more. It was underevaluated in all sorts of respects.”

Dudot concurs: “We were alone. A new team, with a new concept, new tyre technology from Michelin and doing everything ourselves. Only Ferrari was doing this and they had a big history.”

1982 was another year to forget for Renault

Grand Prix Photo

By the end of ’83 and the lost championship, this core of adventurers had been moulded into a team of hardened racers, with only the conservatism and inertia that is part of any big corporation holding them back preventing them, for example, from retaliating when Brabham made its rocket fuel leap in the second half of the year. But those corporate constraints became tighter, not looser, following the ’83 debacle. It was a development accentuated by the replacement of president Bernard Anot, a racing fan, by Georges Besse, who then nominated production car man Gerard Toth as team chief after Larrousse left at the end of ’84.

It was the beginning of the end. Derek Warwick signed as Prost’s replacement believing he’d made the big time, only to see that dream as well as the original one of Castaing, Boudy and Dudot crumble around him: “There were some super people there in ’84, hard-nosed racing pros. But at the year’s end we lost most of them and they were replaced by people from the production car company who had no knowledge of racing. The ’85 car was diabolical, the whole thing turned to shit.”