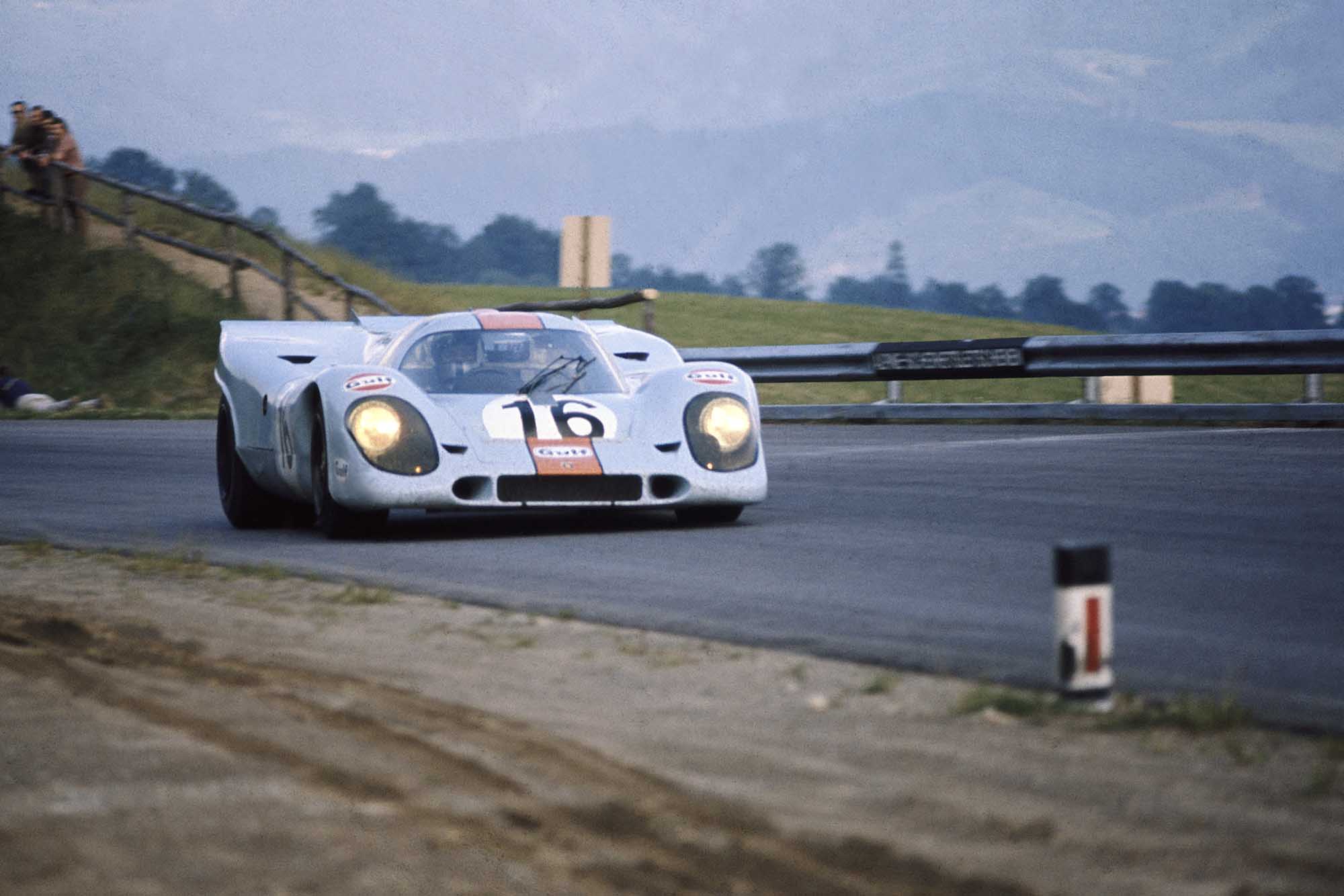

Pedro Rodriguez's Final Fling

Ever wondered what was the greatest wet weather drive of all? Mark Hughes recalls Pedro Rodriguez's last laugh.

Motorsport Images

The Forgotten Races – 1971 Osterreichring 1000km

In retrospect, the 1971 Austrian 1000km for sportscars was a poignant event for all sorts of reasons. But at the time, that damp June afternoon when the cruel cards that fate held up its sleeve were unknown, it was just a plain thriller of a race.

Though he didn’t know it, this was Pedro Rodriguez’s last drive in a Porsche 917, the car with which he became synonymous. Many reckon it to be his greatest. It was the last time a 917 would win a world championship event, the legendary machine having been outlawed by new rules for 1972. It was the last time, therefore, the sport would see one of history’s most awesome cars raced by one of the greatest of drivers. And boy, did he go out on a high.

By 1971 the 5-litre 917 had around 630bhp but, more to the point, had been developed extensively from the brutal machine that first took to the track in Richard Aftwood’s hands in 1969 (see Motor Sport, February 1998) to become a finely-honed racing tool. Attwood is able to attest to this; after finishing second at the ’71 Le Mans, he was called in to partner Rodriguez in Austria as Pedro’s regular partner Jackie Oliver had been fired for breach of contract after driving for Shadow in CanAm.

“The car by that time was as near-perfect as you could ask for,” says Attwood, “though I felt I hadn’t had anything like enough time in it. In practice I sneaked in an extra lap after they’d shown me the in-board because I wasn’t happy with the time I’d done; that last lap got me to within about 2.5 seconds of Pedro. There was more to come but they didn’t need it; I was there to hold the fort really. The first corner after the pits was fantastically fast and you turned in over a crest, so you couldn’t see where you were heading. I think that corner was the ultimate test and I was watching in practice as Pedro went round and he was absolutely flat through it. So was Siffert. I was nowhere near flat. I asked Pedro afterwards how he did it and he said: ‘It’s easy. You just go flat.”

“I asked Pedro afterwards how he did it and he said ‘It’s easy. You just go flat.’”

Such a performance put Pedro’s Gulf 917 on pole at over 130mph, its flat-12 exhaust note rasping across the valley in which the wonderful circuit lay. But alongside him, in an open Ferrari 312P, was an adversary with whom he was very familiar. Only a week earlier, he’d fought him wheel-to-wheel for much of the Dutch Grand Prix, leaving the rest of the F1 field over a lap in their wake. His name was Jacky Ickx and the only man on the planet at that time who could legitimately have challenged Rodriguez’s claim as the fastest wet-weather driver of them all.

Ickx won that race at Zandvoort but only after it had started to dry and a fuel metering problem slowed Pedro’s BRM. There was unfinished business here. Ickx’s 312P was, in essence, his 312B F1 car with enclosed wheels. Though its flat-12 was perhaps 200bhp down on Pedro’s 917, it was a lighter, more lithe device and had already proved competitive against bigger machinery. Giunti had pushed Rodriguez hard for pole on the car’s debut in Argentina and at Brands in April Regazzoni claimed pole ahead of all the Porsches. “It was a fantastic car,” he remembers. “It felt like our F1 car really. Through the corners it was very, very fast and it was only on top speed at fast circuits that a 917 could leave it.”

Regazzoni caning the Ferrari 312P to try and keep Pedro at bay

Motorsport Images

But it was Pedro’s 917 which led as the lights turned green for the first of 170 laps of the Osterreichring. He pulled away from lckx at around two seconds per lap. After Ickx came Herb Muller’s soon to be crashed Ferrari 512S, Helmut Marko in the Martini 917 (giving ABS braking its race debut), and Siffert in the second Gulf 917 (later to retire with clutch and gearbox problems).

Pedro seemed to be running away with it, though he was perhaps mindful that his co-driver Attwood was less competitive than Ickx’s partner Regazzoni and would need a cushion to maintain their lead. All seemed to be going to plan until the 29th lap when a serious misfire suddenly afflicted the Porsche. As Pedro crawled to the pits, Ickx flashed into the lead, 45sec clear of Marko.

The JW Automotive crew traced a battery problem – John Wyer blamed Pedro for using his headlights too much – and set about replacing it, not the simplest of jobs in a 917. It took almost six agonising minutes, with Pedro sitting impassively in the car watching his lead turn into to a 2 1/2 lap deficit. But just as he rejoined down in seventh place, so it started to rain.

Rodriguez was now at his spellbinding best. Better, thought John Wyer, even than in the rain at Brands Hatch the year before. His capacity for driving absolutely flat-out for long periods of time was never better demonstrated than here. The 917 was being driven at a completely different pace to any other car on the track; even lckx, in a lighter, nimbler car, was almost three seconds a lap slower. It was the performance which led Wyer to believe Pedro was the world’s number one, regardless of category.

“I don’t think anyone could have been faster than Pedro in that car at that time,” says Attwood now. “Whether he was the best in the world in F1 terms, I don’t know. But here and at Brands, he was against some great wet weather drivers and he was on a different planet. He’d gone to the Porsche team, where Siffert was known as the greatest Porsche driver of them all, and yet by ’71 Pedro had become clearly quicker than him everywhere. I think Pedro was only just reaching that level of performance.”

On the 44th lap, Ickx came in to change with Regazzoni who resumed without losing the lead, though he was being caught by Marko who passed the Ferrari six laps later. The next car to pass was Pedro’s 917 as the Mexican unlapped himself for the first time, quickly pulling away still with a further two laps to recover.

Pedro celebrates the last win of his life. He died a fortnight later

Motorsport Images

Despite the seemingly impossible odds, there was a certain inevitability about his progress. It was as if all his previous drives had been merely rehearsals for this, his day of days. Given he had only two weeks of life left in front of him, it’s incredibly poignant.

“I never envisaged Pedro living a long life,” says Attwood. “I’m not not saying he had a death wish but he left no margin for error.”

Even Regazzoni and Marko’s battle for the lead seemed only a backdrop to Rodriguez’s mesmerising progress. As Reggazoni’s fuel load lightened he was able to retake the lead and pull away. By half-distance though, Rodriguez had passed the two Alfa T33s to go third, now just 1 1/2 laps behind Regazzoni. Still the rain fell.

When Regazzoni refuelled and changed over with Ickx, it briefly put Rodriguez on the same lap as the Ferrari but then he too came in. Attwood climbed aboard and though he held position, the 917 no longer gained on the cars ahead. “My stint was completely uneventful,” recalls Attwood. “I didn’t pass anyone, no-one passed me, I kept it in one piece while Pedro had a rest.”

After 13 laps was Pedro re-installed, Ickx going past to put him two laps down again. Though the rain had eased, the Mexican had not. On the 120th lap he overtook lckx to regain a lap, still needing to do this twice more if he was to lead. Then Larrousse crashed the second place Porsche out of the race.

“It was as if all his previous drives had been merely rehearsals for this, his day of days”

On the 144th lap Rodriguez passed Ickx again to put himself on the same lap. Incredibly, he’d made up over 100 seconds in 24 laps. He then came in for his final stop. When Ickx came in a lap later he handed over to Regazzoni, delaying the Ferrari slightly. Now Pedro was 91 seconds behind with 26 laps to go. He duly began carving 3.5 seconds a lap from Regazzoni bang on target. His 145th lap took him 39.35s (132.9mph), an outright circuit record, over a second faster even than the best F1 lap of that time.

Would Pedro have done it? We didn’t get to find out because on lap 148 Regazzoni suffered a suspension breakage. “Something broke at the end of a straight,” recalls Regazzoni of the incident which sent the Ferrari into the barrier. Does he think Pedro would have caught him? “Maybe he would have caught me,” he laughs, leaving unsaid the small matter of him getting past.

Rodriguez claimed one of the most improbable victories of all time. When he climbed out, no sweat fell from his face and his hair was completely dry; it evidently came that easily to him.

Two weeks later Pedro drove in a minor race at the Norisring. We lost a giant of a driver when his Ferrari crashed out of the lead, perhaps the greatest of his time, even though this was not recognised in the ultimate arbiter of stature that is Formula One.