In itself, that was a significant achievement, but the intriguing thing about the Coopers was that they had the ambition, the bare-faced cheek, to aim higher. In 1952 the dingy garage in Surbiton was the launchpad for Cooper’s first ‘proper’ racing car, the conventionally front-engined T20. It handled as well as anything Ferrari and Maserati were making, but the Coopers couldn’t find an engine to do it justice. A blond, bow-tie wearing Englishman called Mike Hawthorn performed heroics with a nitro-methane boosted Bristol-engined car, and finished third in the British Grand Prix. That was better than the well-funded BRM V16 ever managed, but Cooper’s Grand Prix aspirations had to wait until a competitive powerplant could be found. The engine that transformed Cooper from the junior leagues to the premier division had similarly humble origins. Coventry-Climax was a forklift truck and industrial engine builder, but there was both enthusiasm for knowledge of motor sport within the company and their FWB engine, originally developed for a fire pump, was widely used in small racing sports cars and single-seaters.

“The aristocrats had been overthrown, but the Coopers were never real revolutionaries”

In 1957 they built a racing engine the four-cylinder 1.5-litre FPF intended for Formula Two. It was the perfect match for Cooper’s mid-engine design and the Climax-powered Coopers dominated, but didn’t have the range or the power to gatecrash the Grand Prix party.

What made the breakthrough possible was not just the development potential of both car and engine, but a change in the Formula 1 rules that made the races shorter and the use of commercial fuel mandatory. On 19 January 1958, Stirling Moss whose first racing car had been a 500cc Cooper drove Rob Walker’s privately-entered T43 to victory in the Argentinian GP.

This was a ‘first’ of the greatest magnitude. The first Grand Prix win for a rear-engined car since 1939: the first for a privately-entered machine; and the first for an independent assembler of racing cars from off-the-shelf components.

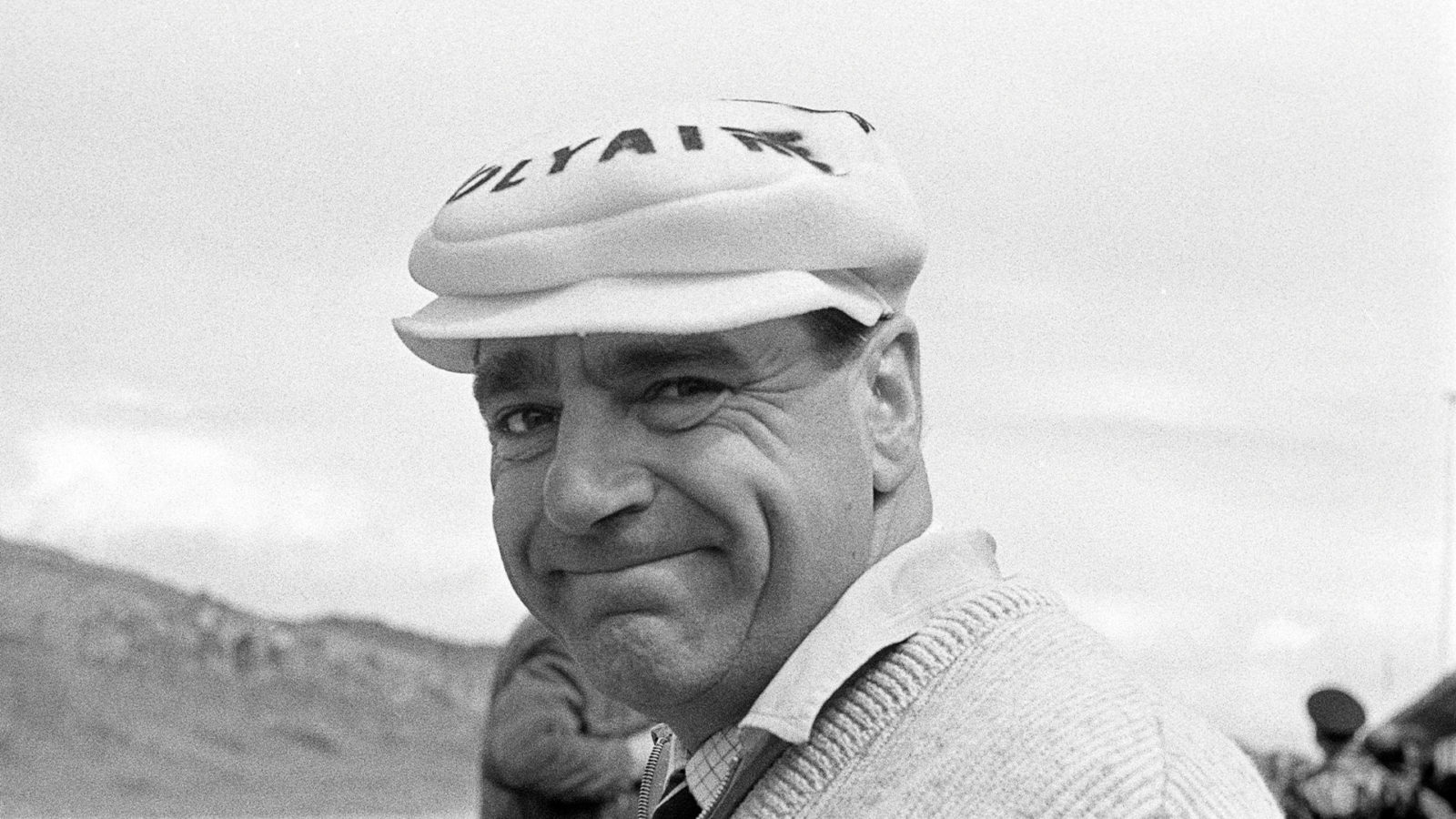

Importance of Brabham to operation was unquestionable

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Veteran Frenchman Maurice Trintignant proved that the win in Argentina was no fluke when he drove the Rob Walker car to victory in the second round at Monaco. And, although the factory-built front-engined cars were to rule for the rest of the season, the Coopers had shown the way ahead.

In 1959 there was room at the top; Maserati and Vanwall had quit, leaving only Ferrari and those perennial under-achievers BRM to compete against. The Coopers filled the vacuum. On a budget of £40,000 (less than £500,000 today) the ‘works’ team won three times and lead driver Jack Brabham took the title. There were two more wins for the marque through the Walker/Moss combination, with other private entrants filling up the grid.