The Wylies were active participants, who built a number of ingenious specials and were happy to devote space to others who created their own cars. They were intrigued by the 500 movement, which originated in the UK and spread Down Under, as more and more people began to appreciate the affordability and competitiveness offered by the tiny lightweight, rear-engined cars. That movement incidentally, laid the foundations for what was to become a flourishing racing car industry in Britain and its eventual pre-eminence in grand prix racing. It sowed the seeds of creative design. The first 500 exponent in NSW was Jack Hooper, who built his car in collaboration with his brother, Bill. Tauranac soon became good friends with them.

It was not long before the Hoopers made their presence felt in the late 1940s, with stunning performances in hillclimbs which occasionally included fastest time of day honours that merited glowing mentions in AMS. During that time, Tauranac — an insatiable reader — was swotting up on racing car design in AMS, the esteemed Laurence Pomeroy’s Grand Prix Racing Car tomes and anything else he could lay his hands on in lunchtime forays to Sydney’s Mitchell Library.

He had learned enough by 1949 not only to start the construction of his first car, but also to write a comprehensive letter to AMS, explaining the causes of understeer, oversteer and rollsteer, relative to suspension design. His interpretations are as applicable today as they were 44 years ago! The car’s subsequent debut, incidentally, was promising rather than auspicious. It was at the Hawkesbury hillclimb, on November 20 1950, at which John Crouch took FTD in a Cooper 1100.

After a couple of years of steady improvement, Tauranac followed up an advertisement for a 500cc MSS Velocette engine. That led him to Hurstville and a haggle over the price with one John Arthur Brabham, who was selling it. Tauranac knew of Brabham through his speedway exploits. The two men — who were like types, practical and down-to-earth — achieved an instant rapport. They had both served in the Royal Australian Air Force towards the end of World War II, Brabham as a flight mechanic and Tauranac as a draughtsman and pilot. Brabham was also a disciple of AMS, which did not neglect to note his progress on the cinder tracks and an occasional fling in hillclimbing.

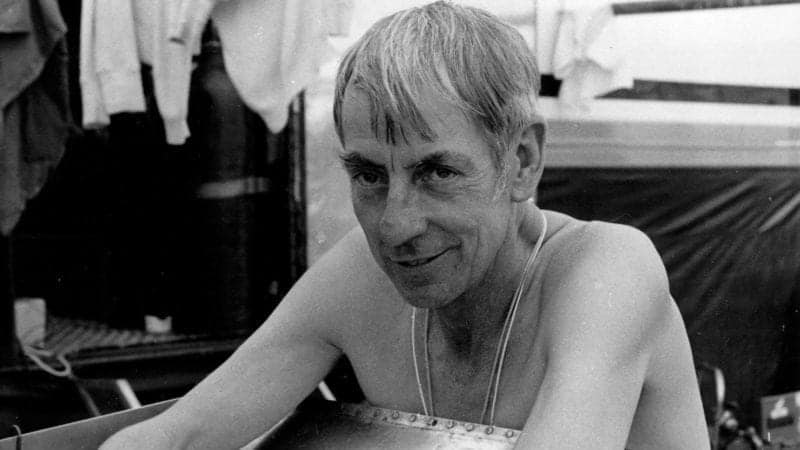

Brabham made modifications to his early Cooper F1 cars on advice from Tauranac

Bernard Cahier / Getty Images

“I was working for CSR Chemicals at the time and one of my responsibilities was sub-contracting machining work for a new plastics plant the company was building,” Tauranac recalled. “When I saw Jack’s small, but well-equipped workshop, I asked him if he took on work. I was looking for people who would listen to my requirements and be guided in what I wanted them to do.

“He thought I meant private work for my racing activities and he said no. But he became interested when I explained it was for a major company. Jack, a fitter and turner by trade, did a very good job and supplied CSR with bits and pieces almost until his first trip to England.

“Because of that association, he ended up machining things, such as flywheels, for my engines. He was expert at that, from doing his own engines for his speedway midgets. In turn, I provided help by way of drawings and advice for the cars he raced. Now and then, I’d use my lunch hour at his workshop to make bits for myself.

“I never got to use the Velocette engine. I prepared it to go into the car, but left it somewhere in Sydney when I eventually followed Jack to England. God knows where it is now!”

Tauranac still has the letters Brabharn used to write to him from his early days in England. “He was always looking for ideas. I sent him some sketches and my concepts were worked into the latest Coopers. There was another time when he wanted to lower the engine. He needed a transmission case with stepped gears, so I drew up a bellhousing and had the patterns made here. Jack took the patterns back after racing in the New Zealand Grand Prix and the new transmission was incorporated into next season’s Cooper-Climax.” Brabham, according to Tauranac, started to think about forming his own team in the late 1950s. But he waited until he won his first championship in 1959 before offering Tauranac a partnership to design and construct cars in England. That was down the track. The first venture was Jack Brabham Conversions, which involved putting Coventry Climax engines in Triumph Heralds, fitting twin Webers on to Sunbeam Rapiers and so on. Tauranac’s nights were occupied with designing the first BT racing car.

First Brabham car – BT3 – at Mexico ’63

Bernard Cahier / Getty Images

The suggested pay was £30 a week — the same amount of money Tauranac was getting in Sydney. “I didn’t know what to do. I was married, with one young daughter. I had a good job in Sydney. And I was also a conservative chap. To get me over, Jack gave me the money for a return airfare, so I could try it for six months and if it didn’t work out, go back to Sydney.

“But I wasn’t going to leave my wife and child, so I spent half the money on a one-way airfare for me and the other half on a passage aboard the Fairsea for them.” Tauranac still had ideas of continuing to race in England, which he soon discarded. “I realised if anything happened to me my family would be stuck here.

“Racing had been a hobby since 1949 and I was actually building a batch of six new cars when I left Australia. Lynx Engineering paid me a nominal sum for all my drawings and patterns. Hillclimbing came first, then road racing, mainly at Mount Druitt. Austin also raced. I designed him a Ford-powered special which he helped to build.

“He also used it as a road car and once towed my racing car and me from Sydney to Bathurst and back, on a rope. We had both intended to race at Bathurst but it didn’t happen. Someone had convinced me to fit a Triumph Speed Twin engine in my car, but the engine threw a rod while we were doing a carburation test.”