The forgotten 1939 Belgrade Grand Prix

With World War II in its first days, the one-off Belgrade GP started with a reduced grid – albeit still manned with exceptional talent. As Ian Bancroft tells, this was a knife-edge moment in history amid a show of German prowess

Mercedes-Benz AG

It was September 3, 1939, an inauspicious date for Europe and the world; the day on which Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany after the invasion of Poland some 48 hours earlier. Yet on the streets of Belgrade – today the capital of Serbia, then of Yugoslavia – five drivers took to the grid to compete in the only grand prix during the Second World War. It is often referred to as The Forgotten Grand Prix, a curious footnote of motor sport history, but one that reminds us about the powers and interests that govern the sporting world.

Dr Marko Miljkovic, a research assistant at the Institute of Economic Sciences in Belgrade and author of The Automobile is Freedom: The History of Automotive Culture in Serbia, 1903-2023, tells how, “the race was the biggest sporting event, proportionally at least, in the history of Belgrade – an estimated 80,000-100,000 of the city’s 400,000 population attended”. Were the Belgrade Grand Prix to be held again today, he has no doubt that a similar crowd would gather.

The temporary street circuit ran through Belgrade’s Kalemegdan fortress, overlooking the juncture where the Sava river flows into the Danube, to continue its course towards the Black Sea. For those unable to afford tickets, the Kalemegdan ramparts offered ample viewing opportunities, though one was required to improvise some shade in the baking sun.

Miljkovic, stroking his bushy beard with pride, compares it to a scene from Federico Fellini’s film Amarcord, also set in the 1930s, where a gaggle of boys take to the castle towers to welcome competitors of the famous Mille Miglia endurance race. Each imagined themselves behind the wheel, attracting affectionate glances from the girls.

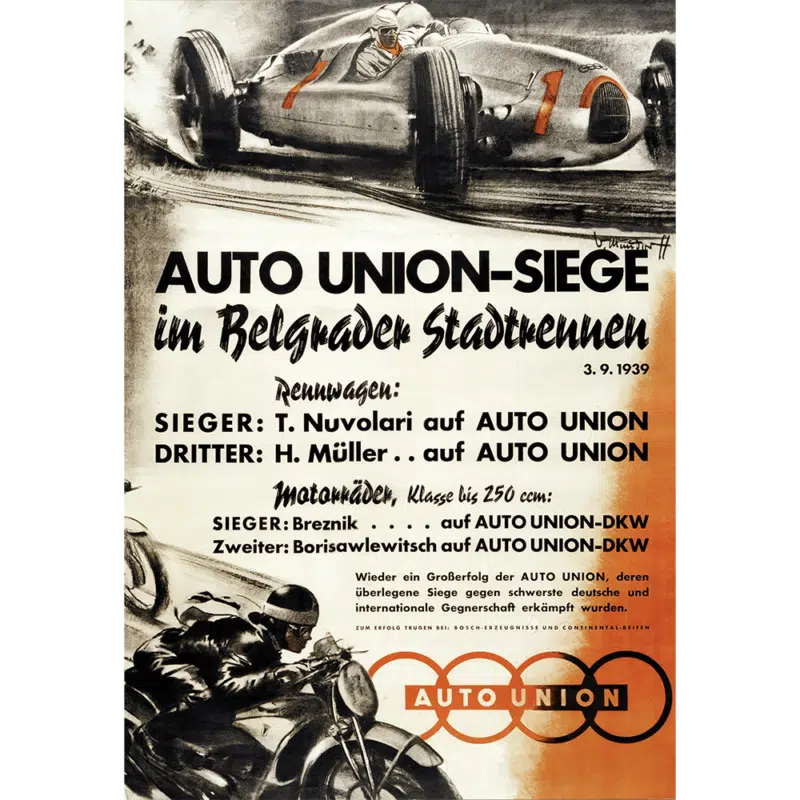

Competition between Auto Union and Mercedes was a major pull for spectators

This was the original street circuit, with tramlines filled in and makeshift stands constructed. Curves were redeveloped and road levels raised by up to 2m at one very fast corner. Kalemegdan’s imposing stone walls, designed to deter military conquest, provided a daunting backdrop for competitors. The city was tarted up for the occasion. Beggars and street vendors were removed; woodworking shops were relocated. A downtrodden neighbourhood, Jatagan Mala, was demolished almost overnight.

The event was originally conceived as a birthday gift to King Peter II Karadordevic, who had acceded to the Yugoslav throne, albeit without any power due to his age – 11 (Prince Paul ruled on his behalf until 1941). His father, Alexander I, had been assassinated in Marseille, France, in 1934, his killing captured on grainy film reel. From the horsepower of military parades that royalty usually enjoyed to the glitz and glamour of motor racing, it was an ambitious project for the entire city. That Yugoslavia was permitted to hold an official grand prix despite an obvious lack of motor racing heritage or experience, however, was down to the pivotal role of Germany.

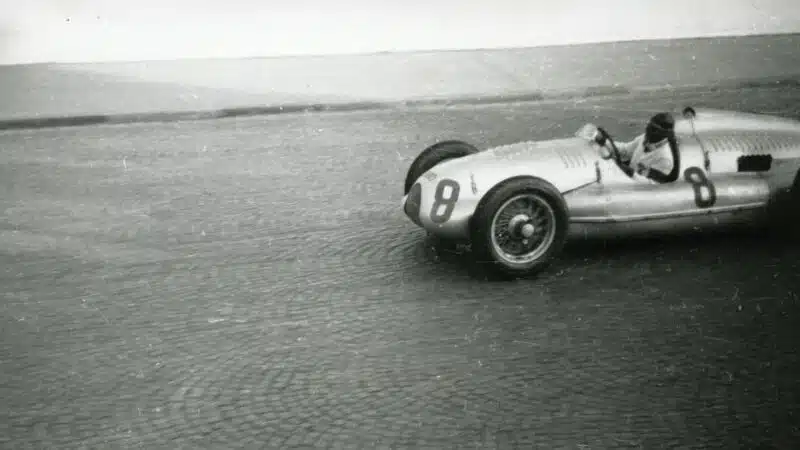

Auto Union’s Hermann Müller steers clear of the city’s tram tracks on his way to a podium finish in a German manufacturer 1-2-3

Mercedes-Benz AG

“Hitler, soon after solidifying his grip on power, wanted to use motor racing for propaganda purposes,” explains Miljkovic, who is also a visiting curator at the Auto Museum Belgrade. It was not untypical for the age. “British Racing Green, French blue, Italian red, German white – each nation was presenting itself and its spirit on the track,” Miljkovic adds. “The Germans wanted to fit the biggest engines they could build, but they were 2-3kg overweight so they scraped off all their white paint – or so the legend goes – and the Silver Arrows were born.”

“The event was conceived as a birthday gift to King Peter II who had acceded to the throne”

But motor racing was much more than a projection of German progress. Developments on the track also served a military purpose. The need for fast, light and compact engines replicated the demands of aircraft. “Mercedes engines could literally be screwed into a Messerschmitt,” Miljkovic contends, while ‘motorising’ a nation meant that “in case of war, there would be plenty of people who could drive tanks”. The ostensible purpose of motor racing, for which there was considerable state support, wouldn’t rouse the concerns of their French neighbours. “Civilian projects were a front for potential – or expected – war,” Miljkovic adds.

Belgrade police keep onlookers away from Von Brauchitsch’s W154; a quarter of the city’s inhabitants lined the streets to watch the race

Mercedes-Benz AG

“Germany was determined to penetrate south-east Europe,” according to Miljkovic, with Yugoslavia gradually drawn into Germany’s economic sphere of influence. The latter’s industrial prowess was used to squeeze the former, often to bemusing effect. “Ten million harmonicas were sent to Yugoslavia, a country of 15 million people. They didn’t know what to do with them but they had to be paid for with raw materials and food.”

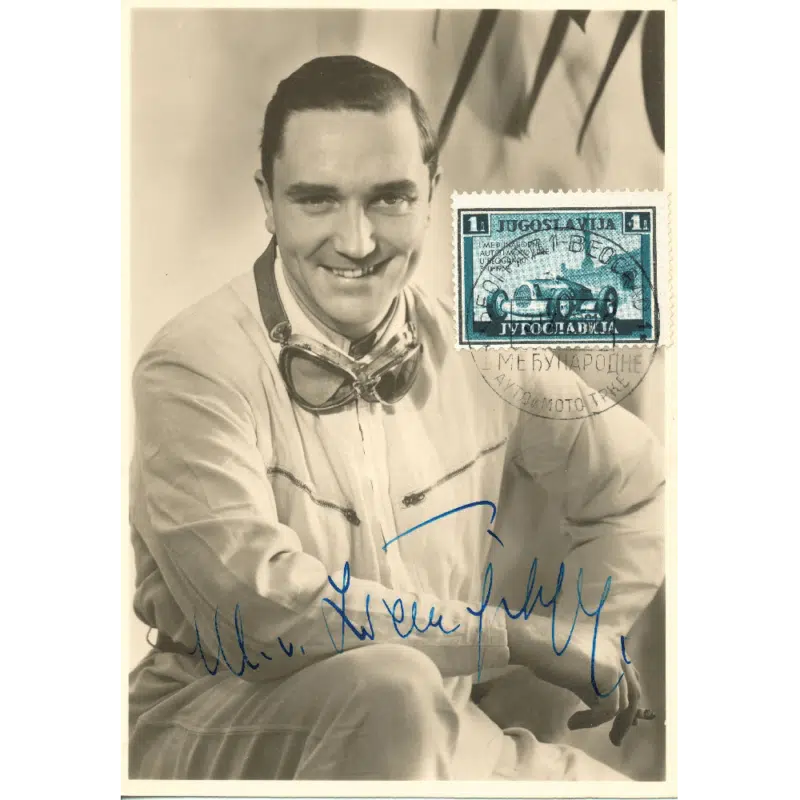

Auto Union’s Tazio Nuvolari, here in Belgrade

German manufacturers quickly displaced their American counterparts, securing 70% of a market once controlled by the US. The 1938 Belgrade Car Show, based on the Berlin equivalent, was dominated by Germans, much to the chagrin of the Americans who complained about a lack of exhibition space. Yugoslavia also endeavoured to mimic aspects of the German development model, especially the extensive autobahn construction programme. A highway linking Belgrade and Hungary was built using German technology. A grand prix in Belgrade provided a unique opportunity to showcase the expertise of the German automobile industry in one of its expanding export markets.

The outdated Bugatti T51 of Bosko Milenkovic stood little change

A predominantly agricultural country at that time, still reeling from massive losses inflicted during World War I, Yugoslavia’s political elites had little room for manoeuvre, especially given the weakness and distraction of their traditional allies. The nature of the relationship is best epitomised by the gift from Hitler of a Mercedes-Benz 770 to Prince Paul Karadordevic. “Paul couldn’t say no,” Miljkovic insists, “but eventually he returned the car without explanation – Yugoslavia was trying to find a balance.”

“Belgrade was not oblivious to the looming threat of war. Preparations were under way”

Belgrade was not oblivious to the looming threat of war. Preparations were well underway. Public lectures were delivered on how to defend against air attacks, with newspapers publishing the complete transcripts and air shelter blueprints. Blackout exercises were held throughout Belgrade, with violators facing strict punishment for noncompliance. Nor were the entrants immune from the mounting anxiety. Manfred von Brauchitsch of the Mercedes team secured pole position under the influence of alcohol. On the morning of the race, he failed to show up for breakfast. As his uncle, General Walter von Brauchitsch, then chief of the general staff of the German army, was planning the destruction of Poland, von Brauchitsch was plotting an escape to neutral Switzerland, only to be intercepted at Belgrade Airport by Mercedes sports director Alfred Neubauer. “Drivers are always presented as men with steel nerves, but they are also human beings – they make decisions for their families,” Miljkovic reminds.

Von Brauchitsch led until late in the race.

Automobile Museum Belgrade Photo Collection

Hermann Müller, 1939 European champion.

Automobile Museum Belgrade Photo Collection

The grand prix offered for many a form of escapism. “At 11am Belgrade time the racing programme began, while at 11am in the UK the country declared war on Germany,” Miljkovic contrasts. He struggles to reconcile two parallels: two contrasting images that epitomise the dilemmas of the day. “On the one hand, people brought picnics, smoked, drank wine and listened to music over the loudspeakers in between races,” Miljkovic says. “There were plenty of kids hanging on trees or out of windows – those who couldn’t afford a ticket. On the other hand, people sat in the shade reading Politika and Vreme, the biggest dailies, with reports about the devastation of Warsaw.”

Cancelling the event was not an option. The official explanation was that the organisers couldn’t afford to lose tons of money, but the reality was somewhat more complicated. “After the annexation of Austria in 1938, Germany was literally on Yugoslavia’s borders,” Miljkovic explains, “and Yugoslavia did not want to provoke a country that had already invaded Poland.” Internally divided, without a strong army, with no allies on which they could depend, there “was not much Yugoslavia could have done”, Miljkovic concludes. “They were trying to swim in the waters while facing the nightmare of the German superpower.”

Hermann Lang

Automobile Museum Belgrade Photo Collection

Late afternoon, the cars assembled on the grid for the 50-lap race, their number greatly reduced by the last-minute cancellation of the British and French contingents. Borders across Europe were closing and general mobilisations were being carried out. Though a limited field, it contained some of the era’s most illustrious drivers. Alongside von Brauchitsch was Hermann Lang, while Hermann Müller and Tazio Nuvolari competed for Auto Union, the predecessor of today’s Audi. The field was completed by Bosko Milenkovic – a private entrant, said to own half of Belgrade, described as “one David against four Goliaths” – who would finish 19 laps down in his old and underpowered Bugatti T51. An eye injury for Lang, caused by a stone catapulted from beneath Von Brauchitsch’s car, meant reserve driver Walter Bäumer took the reins early in the race.

Locals enjoy the spectacle

Automobile Museum Belgrade Photo Collection

In the weeks prior to the race, there was considerable speculation on the streets of Belgrade about other Yugoslav nationals who could go wheel to wheel with the stars of European motor racing. Radoslav Pusic, a chauffeur and car mechanic at the National Bank, made a public call for an appropriate vehicle, though preferably an American one. Dusan Raskovic, a postman, believed his daily journeys throughout the city made him the most suitable candidate. Others took out newspaper advertisements seeking racing cars.

With the commencement of the Belgrade Grand Prix, the roar of engines was heard across the city. Heading into the fast bend by the French Embassy, Von Brauchitsch spun and lost the early lead. With a nod to the Monument of Gratitude to France erected in 1930 as a tribute to Paris’s military support during World War I, the drivers descended towards Belgrade Zoo, whose animals would be killed by a Nazi bombardment in 1941; albeit with one notable exception, Muja, an alligator from Mississippi, who arrived in 1937 and is still alive. They continued towards the Danube, past Nebojsa Tower, once home to artillery canons, where Bäumer was forced to retire after hitting a tree, before sweeping back towards the Embassy. The track covered a little over a mile and a half, much of it cobblestones and bathed in late-afternoon shadow. The crowd created a raucous atmosphere, encroaching further upon the track as each lap passed. They heaved in unison, cheering on whichever driver had assumed the lead. “There were only German teams, German flags, and German emblems,” Miljkovic describes.

After Belgrade there would be no GP racing in Europe until 1945, by which time the city had been heavily bombed

Automobile Museum Belgrade Photo Collection

It was therefore fitting that the Italian maestro Nuvolari emerged victorious, despite arriving late to Belgrade and starting from the back of the admittedly small grid due to a last-minute engine change. The race further cemented his reputation as one of his generation’s leading drivers and advertisers would look to capitalise upon his success in the subsequent weeks and months. War should not be allowed to get in the way of personal liberty, especially as it had yet to arrive in Yugoslavia.

“Though a limited field, the grand prix contained some of the era’s most illustrious drivers”

The post-race celebrations continued well into the night, a mix of relief that the race had been held and apprehension about what lay ahead. Tomorrow would bring not only hangovers but new headaches. Grand statements and gestures were shared, events elsewhere in Europe making them irrelevant and even flippant. Poland was not mentioned. A few days later Yugoslavia would reassert its neutrality and commitment to peace, so long as its independence was not threatened. The contradictions of this approach were clear, and the country could and would not be the arbiter of its own future.

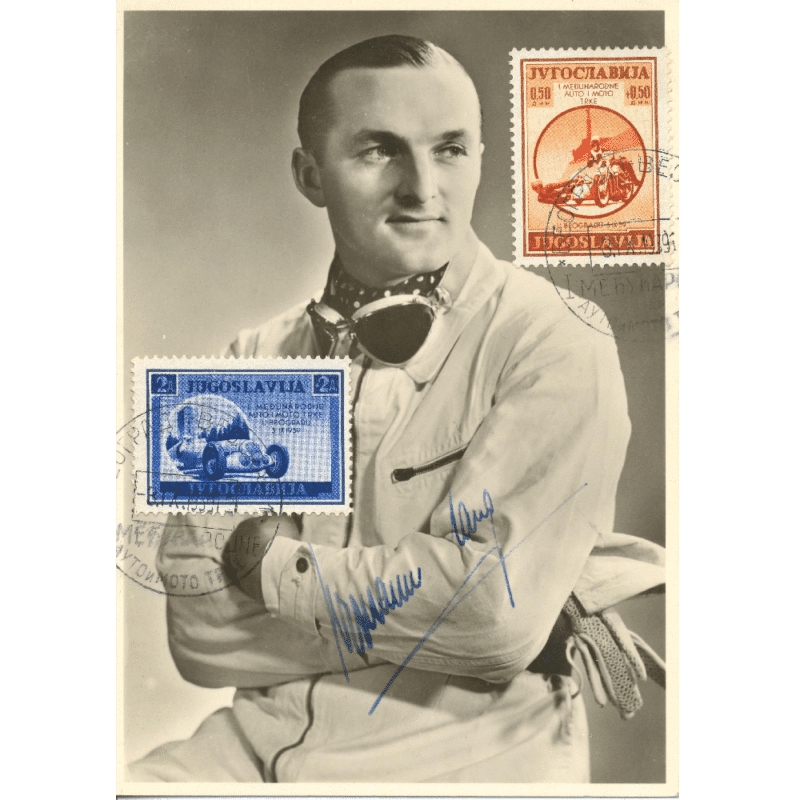

Driver postcards with stamps could be bought – including von Brauchitsch

You could get special postmarks too, as seen on this Lang card

This would be the last grand prix in Europe until a series of races, including the Liberation Trophy, took place on September 9, 1945 in Paris, one week after the war’s end. Neither Yugoslavia nor the states which emerged after its bloody collapse in the early 1990s have held another grand prix. Every year a group of motor sport enthusiasts gather in Kalemegdan to evoke some of the second and third hand memories of that unusual day in September 1939.

For those concerned by Formula 1’s contemporary dalliances with controversial regimes – the term ‘sportswashing’ is now common parlance – the 1939 Belgrade Grand Prix is a timely reminder that political and power considerations have long determined where races are held. Motor sport is often used to project values and ideologies.

Top-level racing would not return to Belgrade and the 1939 running was never officially commemorated in Yugoslavia’s Communist era

In this regard, the current era differs little from the past, save that it is no longer nationalism that determines where races will be held next. Instead, countries keen to project a modern, progressive image to the world will bend over backwards to entice the Formula 1 circus to its door. Purely sporting considerations now rarely exist. As with Belgrade in 1939, so with the new additions to the F1 calendar.