Michael Mann: ‘I had to make Ferrari film the right way otherwise I didn’t want to make it at all’

Hollywood director Michael Mann spent 30 years trying to make his Ferrari movie. Finally, he has achieved his ambition. He tells Damien Smith how, and why it matters

Getty Images

The release of Ferrari this month is the culmination of an odyssey that spans 30 years for director and Hollywood big-hitter Michael Mann. The film-maker was in his fifties when he and his friend, fellow auteur Sydney Pollack, first started work with screenwriter Troy Kennedy Martin on a story based on Brock Yates’s colourful biography Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine. The revered Pollack died in 2008, but Mann, now 80, has finally achieved that ambition of bringing his vision of Enzo Ferrari – set in a tight three-month timeframe during 1957 – to life on the silver screen. This one was personal.

For years stories would emerge about this movie, then vanish. Robert de Niro, with whom Mann worked on his masterful crime thriller Heat, was an early candidate to play Enzo. Much later, in 2015, Batman star Christian Bale was in line, but was said to have pulled out because he didn’t have enough time to put on the weight he felt was essential to become Enzo. Hugh Jackman (aka Wolverine) was subsequently on board, until 40-year-old Adam Driver, among the finest actors of his generation and best known for playing Kylo Ren in recent Star Wars films, took the role. So why did it take so long?

Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver) leans in for a word with Peter Collins on the set of the film as photographer passenger Louis Klemantaski braces himself for more action

“No car racing movie – and this is categorised in that sub-genre – had ever done well at the box office. Ever,” emphasises Mann – who enthusiastically agreed to speak to Motor Sport exclusively for this story because he happens to be a reader. He cites the two big racing pictures, John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix and Steve McQueen’s Le Mans – upon which his father’s second cousin, Saul Bass, worked – as the prime culprits for turning Hollywood off motor sport. “The visual romantic allure of racing was always there, but those earlier films didn’t have a story,” says Mann. “Beautiful visuals will keep your attention for about eight minutes and that’s it, then the story better show up.

Michael Mann’s attention to detail meant Ferrari was an expensive film to make

Lorenzo Sisti

“The first one that really had a great story was Ford vs Ferrari (aka Le Mans ’66).” Mann was “tangentially involved” as an executive producer on the 2019 movie in which Bale did star, as a skinny Ken Miles, sharing the lead with Matt Damon as Carroll Shelby. What was key to its success to a wider audience far beyond car enthusiasts, says Mann, was “unusual characters” that “resonate with how life really is”. That’s also key to Ferrari’s long-awaited existence.

A mix of genuine cars and clever recreations are used

Lorenzo Sisti

Driver is one of Hollywood’s bankable A-listers – and Mann reveals both he and his lead, plus other key producers, took “a radical salary cut” to get Ferrari off the blocks. “But it could only be made the right way,” says Mann. “It was an expensive movie to make” – the budget was said to be £75m – “because we had to build replica cars. I shot it to a relatively quick schedule, too – 58 days, when it should have been typically 75-80. But it had to be made the right way otherwise I didn’t want to make it at all, which meant being up in the ozone of budgets.”

“Adam is grounded in a gritty reality. He was the perfect Enzo”

Driver looks nothing like Enzo Ferrari and from what we can tell didn’t bulk up in the way Bale apparently felt was necessary. But he does deliver an intensely magnetic performance, laced with pleasing hints of Enzo’s dark humour. “Adam has within him this power and strength that was there in the core of Enzo,” says Mann. “There’s a specific moment in time as described in the Richard Williams book [Enzo Ferrari: A Life], when Enzo was sitting on a park bench in Turin in 1918 when he had been turned down by Fiat for a job. He’s bereft and cold, brushes snow off a bench. His father and brother are dead, he has little education and no money. As he says in his autobiography he openly wept, in a moment of crushing despair. But he asked himself one question: who shall I be in this world? And that’s such a romantic notion.

“Ferrari had a belief he could transcend static class hierarchies in Italy in 1918 and make of himself what he wanted to be. The first incarnation was as a race car driver in the 1920s. At the core of Adam Driver is that same raw ambition. He applied to Juilliard” – New York’s famous performing arts college – “straight after high school and got rejected, went to the marines for three years, came back and did make it to Juilliard. He has lived in the world, is grounded in a tough and gritty reality. To me he was the perfect Enzo.”

As you’ll have gathered if you’ve read Richard Williams’s story elsewhere in this issue, Ferrari is far from a straight car movie. Rather, it’s an emotional drama surrounding Enzo, his wife Laura – played with a wonderful mix of power and vulnerability by the superb Penélope Cruz – and the so-called mistress, Lina, portrayed with subtlety by the equally adept Shailene Woodley. This is a film that’s as much about the women as Enzo, and it’s all the better for it.

Michele Savoia plays a convincing Carlo Chiti

Eros Hoagland

“The stories of Enzo and Laura are legendary,” says Mann. “There’s a restaurant in Piazza Roma in Modena called Oreste. The former owner recounted to us how Enzo and Laura would argue at great volume in there. It’s a relationship that exists in life, then Troy, Adam, Penélope and myself made drama out of it. These are two people who can’t live apart, can’t live together. Enzo described her when he met her, how he fell head over heels in love when she was singing in cabaret. They formed this family together, had their son Dino. She pawned his wedding gift to buy the rest of the components for his first car. She was a partner, sharp and smart – cynical, but also primal in her beliefs.

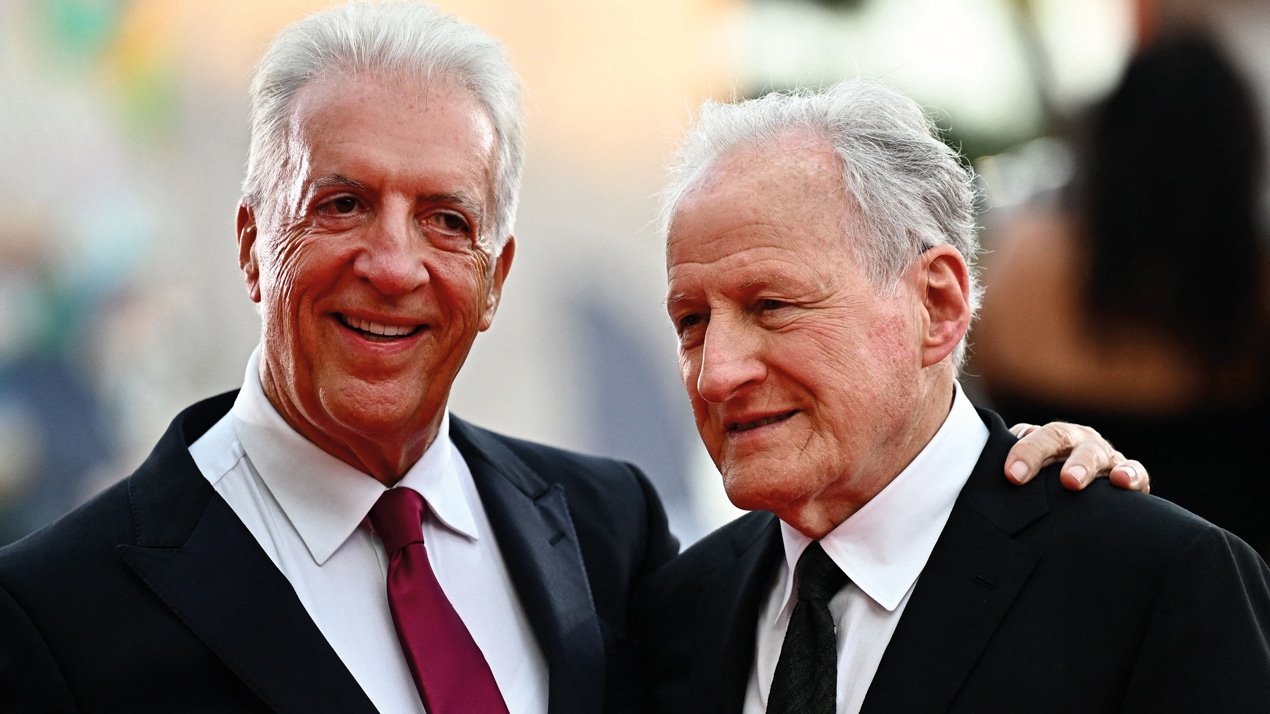

Michael Mann, right, with Piero Ferrari, the only living son of Enzo, at the Venice Film Festival, 2023

Getty Images

“But that extrovert woman became locked in a silo of mourning after Dino died, with Enzo in his own. There’s this cloying term of ‘healing’, but there was no healing. Losing a child is the most unnatural thing. They exist outside of psychology – it’s not like they would go to a therapist. It continued for years, this relationship of hostility, anger, dependency. But when he was having his biggest fights with her the person he still called about business was always Laura.”

Maserati vs Ferrari in Mann’s recreation of the 1957 Mille Miglia.

Eros Hoagland

There are other sources beyond the Yates biography. “We met Laura’s doctor who was quite elderly and he showed us letters no one had ever seen, letters Enzo had written to Laura in the middle 1970s [she died in 1978]. They are incredibly affectionate. It’s a really compelling dynamic and no one could personify Laura better than Penélope Cruz. I knew in four minutes on a Zoom call with her that she was Laura. She had a total understanding of this woman.”

“Lina is described as a mistress but really she was a second wife”

The movie centres around Laura discovering the existence of Lina – and of Enzo’s illegitimate son, Piero. Once confined to being known as Piero Lardi until Laura had died, Piero Ferrari gave Mann his full blessing. “I can’t imagine the anticipatory anxiety he must have felt,” says the grateful director. “Here we are making a motion picture about his life as an illegitimate 12-year-old. We’re portraying his mother; Laura with whom he had a difficult relationship; and his father. I’ve known Piero for more than 20 years and I am the beneficiary of a lot of personal trust. We spent a lot of time together, including in pre-production talking about the kind of details that are critical while making such a film. Like what time did your father get up? Did he wear pyjamas? What kind of pyjamas?

For Mann, Ford v Ferrari, below, mixed racing authenticity with a winning story – unlike Grand Prix -below

Getty Images

“We learnt a lot about Lina that’s not in the books, primarily from her niece – everyone says she is a lot like her. Lina was very contemporary. She’s described as a mistress because people don’t know what to call her, but she wasn’t one. It really was a second family, she was a second wife. When Enzo had important clients he was friendly with he’d take them home to Lina’s, and she’d home-cook a dinner for eight people. The only images of Enzo in repose, lying on the grass with his shirt open, are at Lina’s house. I don’t think single mothers were all that unusual in Italy 10 years after the war.”

Grand Prix, which the Ferrari director partially blames for turning the US public off racing movies

Getty Images

The film evokes 1950s Italy beautifully and there’s loving detail in every frame. But as Richard Williams has touched upon, Ferrari plays fast and loose with racing and company history in a manner that’s likely to make readers blanche. Examples? Jean Behra (played by Derek Hill, son of Ferrari world champion Phil) is built up as the Maserati rival Ferrari must beat to win the Mille Miglia – until he trundles down a bank, smacks a rock and retires. Piero Taruffi (an underused Patrick Dempsey) stops to give Behra a ride – in a race the Frenchman never actually started. In reality, a broken wrist incurred during a practice crash ruled him out. Then again, perhaps historical accuracy is over-rated… Scroll back to Denis Jenkinson’s report for Motor Sport in the July 1957 edition, see overleaf, and you’d never know the accident that killed Alfonso de Portago and his co-driver Ed Nelson also claimed the lives of nine spectators, five of them children. Jenks pays passing brief tribute to the crew, but makes no mention of the horror that ultimately called time on the 1000-mile road race. So much for the organ of record.

Genuine artisan skill was employed to create the racing replicas

Eros Hoagland

What Mann says he has been careful about is the depiction of that accident which occurred at Guidizzolo, less than 40 miles from the finish in Brescia. He’s a director that’s rarely shied away from contextual violence and here he’s chosen an unflinching approach to the terrible brutality of the tragedy. It fully earns the movie’s rating as a 15 in the UK. “It’s faithful to what happened, both out of respect and the meaning of that accident,” he maintains.

Police and investigation reports were his source – plus, he reveals, one very special eye-witness. “We visited the site at Guidizzolo. While we were there, an elderly gentleman with a cane came out. He asked what we were doing. When we explained, he said: ‘I was there.’ He said his family were having their Sunday dinner when they heard the first cars come through. ‘My older brother, who was nine, ran out,’ he told us. I was three. I ran after him, I was slower and he got to the edge of the road – and my brother got killed. I saw the whole accident.’ That inspired the scene of the farm family with the three-year-old toddler.”

Mann, left, filming The Last of the Mohicans.

Getty Images

How it’s shot, with an inevitably heavy use of obvious CGI, is also influenced by period footage of another racing tragedy. “The famous accident at Le Mans in 1955,” says Mann. “The way that comes to you in the existing film footage is the way I wanted to see this. The horror is in how plainly it’s shot. No artifice, not a lot of cutting. The honesty of the news reel footage of the Le Mans accident influenced how I shot it. A simple pan shot and you see what happens, no games and no tricks.”

The final shot lingers on what’s left of de Portago, played by Gabriel Leone. “That was absolutely the way to show it,” Mann insists. “It’s horrible. What happens in such an incident is what happens to human bodies when they fall out of aeroplanes, how they come apart. I left out some of it and the gruesome details of what happened to Ed Nelson but I also didn’t want to censor it. We move on to Brescia and Taruffi’s victory. Of course, they have no idea this has happened.”

Its curtains for the No6 Ferrari in 1971 film Le Mans

Getty Images

Mann says he drew on his own limited racing experience for the other action sequences, which share a style recognisable from Ford vs Ferrari and perhaps also Ron Howard’s Rush. In other words, not a patch on the realism of Le Mans, which remains the benchmark in this regard. “I did some amateur racing,” Mann explains. “As a director or actor if you have a fraction of an experience you know how to project or extrapolate it. It was enough to say ‘I get it’.

“I wanted to subjectify people to the internal experience of driving”

“Racing lends itself to beautiful shots, and pushes the audience into the role of observer. I didn’t want that. I wanted to subjectify them to the internal experience of driving. The last thing you are conscious of when you are driving is what’s happening to you in that moment. You are conscious of what you are doing next. When it’s working it’s what Jean Behra called ‘ridiculous ecstasy’.”

Gabriel Leone plays tragic Alfonso de Portago, foreground, with Jack O’Connell as Peter Collins

Eros Hoagland

Such a film is always going to be aimed at a wide audience, but as a genuine car enthusiast you sense he can’t help but care about how it will be received by true racers. “The most critical audience for me was when I screened it in Modena for about 200 engineers, designers, executives and people from the Ferrari race team,” he says. “They had a positive reaction to the picture. That was critical. When you make a film like this, whether it’s Modena in 1957 or the American frontier in 1757 and you embrace Iroquois culture” – referencing his 1992 film The Last of the Mohicans – “it’s kind of the same thing.”

His final word on his audience is also revealing. “We do quite a bit of testing,” Mann explains. “The demographic that responds to the movie the strongest is women over 35, and then men over 35. I think that’s to do with people who have lived life: had children, perhaps had a marriage that didn’t work. Hence the strong connection to Enzo and Laura.” But it’s not just the movie’s human emotional pull that resonates. “It’s interesting. The favourite component for women is racing as well as the story. If you look at who is watching racing now in the wake of Drive to Survive, the interest from women is soaring.”

Costs were high on the film but the results are worth it

Lorenzo Sisti

Like it or not, his film will be labelled a racing movie. But perhaps where it breaks the most important new ground is who might enjoy watching it the most – while training a welcome spotlight on the women who influenced, and had to live with, motor racing’s greatest, most enigmatic and plain difficult figure. It’s about time.

Ferrari is on general release now.