Eric Crudgington Fernihough: Biker who took on the Nazis and won

In the 1930s Eric Crudgington Fernihough was obsessed with becoming the fastest motorcyclist on Earth on his supercharged Brough Superior. But he had some strong competition in the Nazi Germany-backed BMW. Mat Oxley tells a tale of British ingenuity, determination and pluck

With a steely resolve and a helmet that wouldn’t have looked out of place in a 1990s Pet Shop Boys video, British motorcycle record-chaser Eric Crudgington Fernihough locked horns with the pre-war sportswashers

Getty Images

Sat in a dusty cupboard in the bowels of the Royal Automobile Club, leafing through ancient volumes of The Motor Cycle and Motor Cycling, the name jumped right out at me. How could it not? Mr Eric Crudgington Fernihough Esq. And the faded photos on yellowing, brittle paper, almost a century old, did full justice to the name: cravat, plus-fours, neatly trimmed moustache and a supercharged Brough Superior.

“Terry-Thomas would have been a casting director’s dream for Ferni”

If I had made this discovery half a century earlier, the actor Terry-Thomas would’ve been a casting director’s dream for Ferni the movie.

Fernihough had been long forgotten, which didn’t seem right. His story was more than worth telling, so I set about researching and writing a book about the man and his adventures. And what adventures!

Fernihough was an orphan, adopted by a wealthy lady, who ended up at Cambridge University in the early 1920s, from where he graduated in chemistry and engineering. Or brewing fuels and making motorcycles, as he preferred to call his studies. The motorcycle bug bit ‘Ferni’ early.

“A quarter of a century ago, very small boy, rummaging in the family wastepaper basket, found a catalogue of motorcycles and their accessories,” he wrote in 1936, at the age of 31. “He kept it, studied it, and from it learned to name the component parts of the machines he saw. It was dearer than any storybook to him, because from it sprung a deep-rooted interest in motorcycles that filled his life.

“Years afterwards the boy used to break bounds from his boarding school and tramp miles to an important road, where, for a brief half hour, he could sit and watch various makes ascending a certain hill and compare their performances. Often he was late back for roll-call, but that, to one who was as obsessed with motorcycles as he was, did not seem important. For, while he was sat in detention, his thoughts were free to fly away to some future time when he himself should own a machine, should tune it, and perhaps, if the gods were very kind, win races on it. That small boy was I…”

The gods were kind to Fernihough. He rode his first race in 1923, at Brooklands, while at university. In those days inter-varsity Oxford vs Cambridge bike races were still a thing.

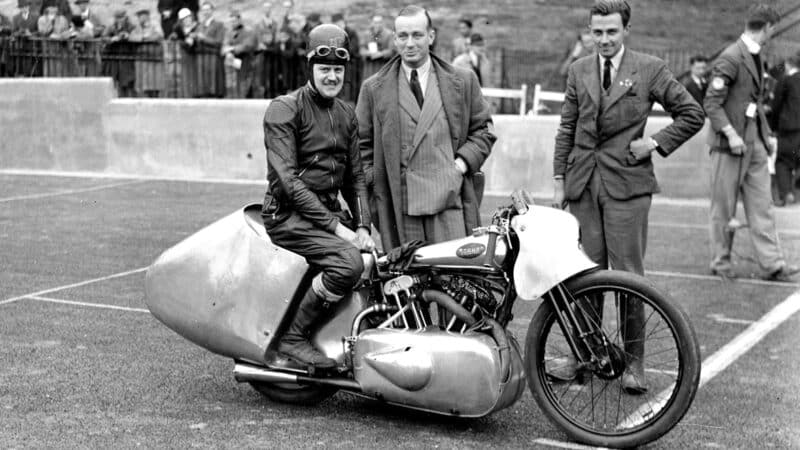

Streamlining on the Brough Superior was pure garden-shed engineering. Eric is showing off his handiwork at Brooklands

Getty Images

In 1927 he contested his first Isle of Man TT but never returned to the island, after friend Archie Birkin died during practice after swerving to avoid an oncoming van. (In those days the roads weren’t closed to traffic during TT practice sessions.) Birkin’s brother was Sir Henry Birkin, a member of the Bentley Boys, a band of wealthy British car racers.

Four years later Fernihough won the European 175cc championship, riding a JAP-powered Excelsior. JAP engines – manufactured by John Alfred Prestwich in a north London factory that employed more than 5000 workers – played a major role in the challenge that defined Fernihough’s career.

In 1934 Ferni set his sights – despite failing eyesight, which required him to wear prescription goggles – on breaking the two-wheel land-speed record to become the fastest motorcyclist on Earth.

The interwar years were the golden age of land speed-record breaking, on four wheels as well as two. Records were often bettered several times each year, as engine and aerodynamics performance climbed a steep upwards development curve.

‘Ferni’, second from left, lived near Brooklands and frequently raced there

Of course, it wasn’t only about getting your name in the record books. Fernihough was chasing cash bonuses offered by tyre, fuel and lubricant companies. He also earned a few extra quid by tuning engines in the workshop situated adjacent to his house, near the gates of Brooklands.

Ferni faced this new challenge almost alone. The only person that offered any real support was George Brough, founder of Brough Superior, the so-called Rolls-Royce of motorcycles, much loved by TE Lawrence, aka Lawrence of Arabia.

Ferni was given two Brough Superior SS100s, built from new and not-quite-new parts. And step by step he prepared for his attempt on the world record.

Fernihough’s greatest rival for the motorcycle speed record crown was Ernst Henne, here shaking hands with Adolf Hitler

Getty Images

In 1936 he fitted a supercharger to the Brough and reached 159mph in the Brighton Speed Trials, the fastest a motorcycle had travelled in Britain.

“When the Nazis came to power, they set about establishing a sportswashing programme”

“Ferni got away like lightning and man and machine roared bullet-fashion into the gloom, the war-song of the big twin punctuated by an occasional misfire,” wrote one observer. “This augurs well for his forthcoming attempt on the world’s speed record.”

However, there was a problem: Adolf Hitler. When the Nazis came to power in 1933 they set about establishing a motor sportswashing programme of racing and record breaking by funding Auto Union and Mercedes. Meanwhile BMW was already busy breaking motorcycle records.

Henne was a darling of the Nazi regime

Stilltime

BMW’s number-one speed merchant was Ernst Henne, also an orphan, who described himself as “a bit of a wild thing”. He once spent nine days in a coma after falling off a road bike. By the time he came around, one newspaper had already published his obituary. Henne broke the motorcycle record for the first time in 1929, riding a 734cc supercharged boxer twin to 134.68mph on a road near BMW’s Munich HQ. By the time Fernihough was ready, Henne had raised the bar to 159.09mph.

Ferni’s first attempt was far from auspicious. In October 1936 he attended Germany’s first Reich Records week, a new event run by the NSKK (National Socialist Motor Corps), established by Hitler to mobilise and mechanise German youth.

When he arrived on the Frankfurt autobahn, guarded by NSKK troops and decorated with Nazi flags, he wasn’t greeted with open arms. This event was designed to showcase German engineering and heroics, not British derring-do.

Ferni at Brooklands before his record attempts

Brooklands

The NSKK needn’t have worried though. Ferni’s supercharged 996cc Brough looked positively medieval next to BMW’s latest creation: a supercharged 492cc flat twin wrapped in an aluminium streamliner. A two-wheeled Silver Arrow.

“He spent the winter learning panel beating and aluminium welding to fabricate his streamliner”

BMW developed this fighter plane without wings in a wind tunnel that was later used to test Messerschmitt and Heinkel warplanes.

And yet Henne had a horrible time with the streamliner. The 492cc engine was all new and a big step forward from its ageing 734cc predecessor. But each time Henne attacked his own record the motorcycle broke into a terrifying wobble. Nevertheless, by the end of the day he had raised the record to 169.05mph.

BMW streamlining

BMW

Meanwhile Fernihough got nowhere, beset by oil leaks, ignition misfires and a burnt-out clutch. Many would have given up there and then, but if Ferni was a brave and talented rider and a brilliant engine tuner, his greatest power was superhuman obsession.

He had the Brough’s magnetos rewired and set off for Hungary, where part of the London-to-Istanbul Transcontinental Highway had been constructed near Budapest, to fit the specifications required for record attempts: dead straight and flat.

Henne’s talents were wide, including racing BMW motorcycles off-road

Getty Images

The Brough ran perfectly on the Gyon road. Ferni broke Henne’s record going one way, but his ageing Sturmey-Archer gearbox stripped a pinion on the second run to give the mean figure required for official records. At least he knew Henne wasn’t out of his reach.

And thus began a remarkable few weeks, during which Ferni criss-crossed Europe in his Fordson van, driving 5000 miles, loping along dusty, bumpy single carriageway roads at perhaps 35mph and completing more than 30 tiresome border crossings.

This was Eric’s first streamliner; it was soon adapted

Brooklands

Back home he rebuilt his engine, replaced the gearbox, loaded up the van and retraced the 1100 miles back to Gyon. This time he reached 167.8mph, which a few weeks earlier would’ve given him the record but was now too slow.

Then home again, where he spent the winter learning panel beating and aluminium welding to fabricate his own streamliner. Ferni knew nothing of aerodynamics and it showed. Nevertheless in April 1937 he set off for Gyon once again, with mechanic Eric Rowland and a young helper by his side. Their first days back at Gyon were spoiled by mechanical issues and bad weather. By day five Fernihough was running out of cash – closing the road wasn’t cheap – and he had to wait until late afternoon before conditions were good enough for a decent run.

Henne first broke the record in 1929, reaching 134.68mph outside Munich

BMW

“Not a miss! Not a stutter!” reported Motor Cycling. “Up went the revs in a howling cadence to peak. Through the approach curve Ferni laid the blown Brough way over in a steep bank; then she was sliding, sliding… Would he, could he, hold that slide? Yes, up she came and down the straightaway like an artillery shell! ‘This is it,’ Rowland kept repeating under his breath. ‘This is it.’ And it was it. Hastiest in the world!”

Fernihough had recorded a mean of 169.8mph, just 0.73mph better than Henne, and was the fastest motorcyclist on Earth. Not for long, though.

With the world record in the bag, Eric was invited to give an exhibition run here at the 1937 Dutch TT

Stilltime

A new player had entered the record-breaking game: Italian marque Gilera, with brilliant rider, driver and engineer Piero Taruffi, who had started racing motorcycles in the 1920s. In 1931 Taruffi was signed by Enzo Ferrari to race both motorcycles and cars. The following year he beat Ferrari’s favourite bike-racer Giordano Aldrighetti in the Coppa del Mare motorcycle race, so the Old Man sacked him.

Taruffi moved to Rome, where he joined the nascent motorcycle and aerospace brand CNA (Compagnia Nazionale Aeronautica), owned by Count Giovanni Bonmartini, a committed Blackshirt and friend of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

The Italians used fighter-plane streamlining on their Gilera. Piero Taruffi, who later won an F1 GP for Ferrari, stole the record from our Eric

De Gier

Bonmartini was building the world’s first transverse inline-four motorcycle, the template for today’s superbikes. His plan was to sell a “two-wheeled Bugatti… a bike which is not suitable for everybody… destined for a few exceptional sportsmen.”

He christened his motorcycle Rondine (Italian for swallow), after the plane he had flown accompanying the 1922 March on Rome, which brought Mussolini to power.

With Europe spinning towards war, Fernihough worked round the clock to uprate his JAP engine

Mortons

However, Bonmartini fell out with another Mussolini henchman, Italo Balbo, chief of the Italian air force. Therefore his hopes of winning lucrative military aircraft orders were finished, so he sold CNA.

“Thousands of German troops were descending on Austria”

The CNA motorcycle project was bought by Giuseppe Gilera, who hired Taruffi to continue developing the supercharged 500cc four. Gilera and Taruffi made their first attempt on the record in the spring of 1937, using the Bergamo-Brescia autostrada, closed to the public by Blackshirt general Ugo Leonardi.

They were unsuccessful. By October 1937 Taruffi was ready for another go, the Gilera also wearing fighter plane-style streamlining, developed by Caproni, another military aircraft manufacturer. Taruffi was a genius at getting the most out of any vehicle. His memories of his next attempt show why.

Fernihough broke the record in Hungary, 1937; he’d die trying to re-take his crown in ’38

Alamy

“The air inside my bubble was calm. I gripped the tank tightly with my knees and pressed my elbows down on them, so that all my limbs were firmly locked, ready to react to the first sign of a wobble…

“Now the finish was coming up. The handlebars started to shake. I braced my knees, lest the slightest movement here should impart larger, uncontrollable tremors to the whole mass of the machine. The forces against me were tremendous. No sooner had I mastered the swerve in one direction than the bike would head off in another; but I must not, on any account, let up. And I didn’t.”

Taruffi, Gilera and Italy were the new record holders, at 170.27mph.

This news didn’t go down particularly well in the NSKK headquarters in Berlin, which demanded an immediate counterattack. But Henne was unable to better Taruffi in the 1937 Reich Records event, because BMW’s streamliner was impossible to control at such speeds. Enter Hitler’s favourite engineer, Ferdinand Porsche, who advised an aerodynamics overhaul.

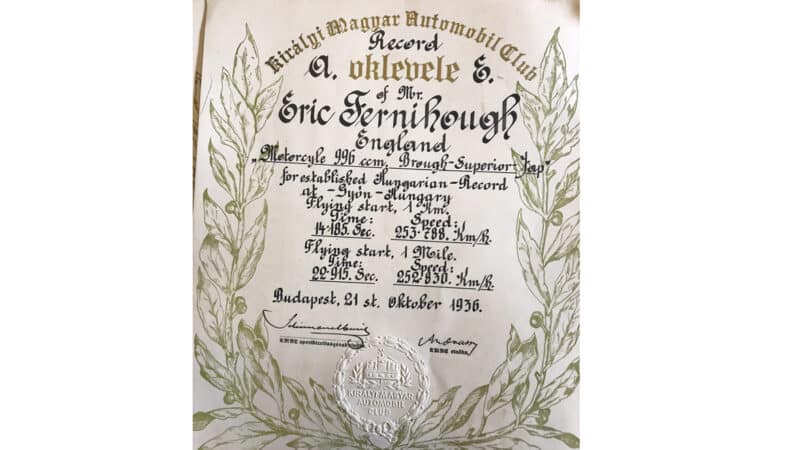

Hungarian record holder, 1936

Mutschler

Porsche’s input worked wonders. On November 28, just five weeks after Taruffi’s 170mph breakthrough, Henne reached 173.67mph on the Frankfurt autobahn. Ferni spent the winter eking more power from his JAP engine. “I get up at 7am and I’m in bed at 2.30am; I merely work and eat.” He knew his Brough was already pretty much obsolete, so if he wanted to recapture the record he must act quickly.

By March he was ready. But global events were moving ahead of him. His progress towards Hungary was slowed by tens of thousands of German troops descending on Austria to annexe the country.

At Gyon the weather was abysmal, so after several days he drove home again. Two weeks later he was once more bound for Gyon. Talk about obsessed…

The Brough now sounded louder and madder than ever. “If it didn’t scare you stiff, it wouldn’t be right!” said Fernihough.

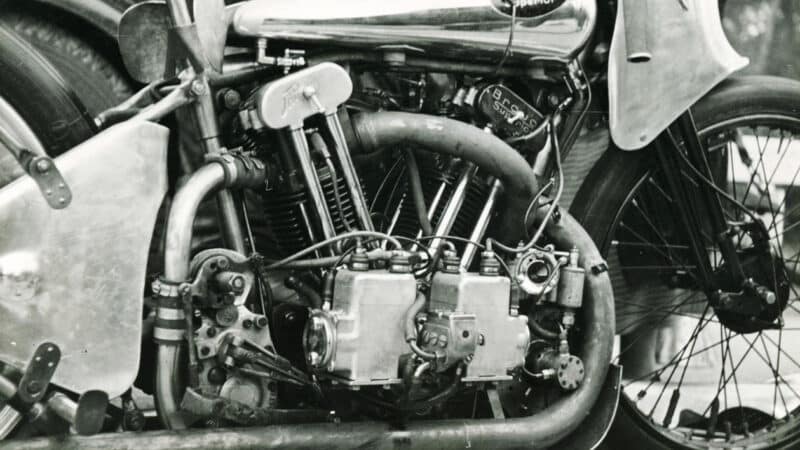

The 995cc JAP engine could propel the bike to 180mph – and along the way was very noisy

Mutschler

On the morning of April 23, Ferni was doing 180mph – according to Rowland’s highly attuned ears – when he lost control and died in the ensuing crash.

The hearse containing Fernihough’s body (packed in ice) was given a hero’s send-off by the Hungarians. A procession of cars accompanied the vehicle from Budapest on the first leg of its sad journey home. Later, BMW representatives escorted the cortège through Munich. Meanwhile Rowland drove home, with the tangled remains of the Brough.

“At every frontier their utter sorrow touched me deeply,” he wrote. “As I left each frontier post the officers lined up and, standing to attention, gave a salute of honour. The sympathy I was shown in Hungary, Austria, Germany and Belgium all went to prove just how much dear old Ferni was loved.”

|

The full incredible story is told in Racing Hitler by Mat Oxley, £27.99, available at matoxley.bigcartel.com |