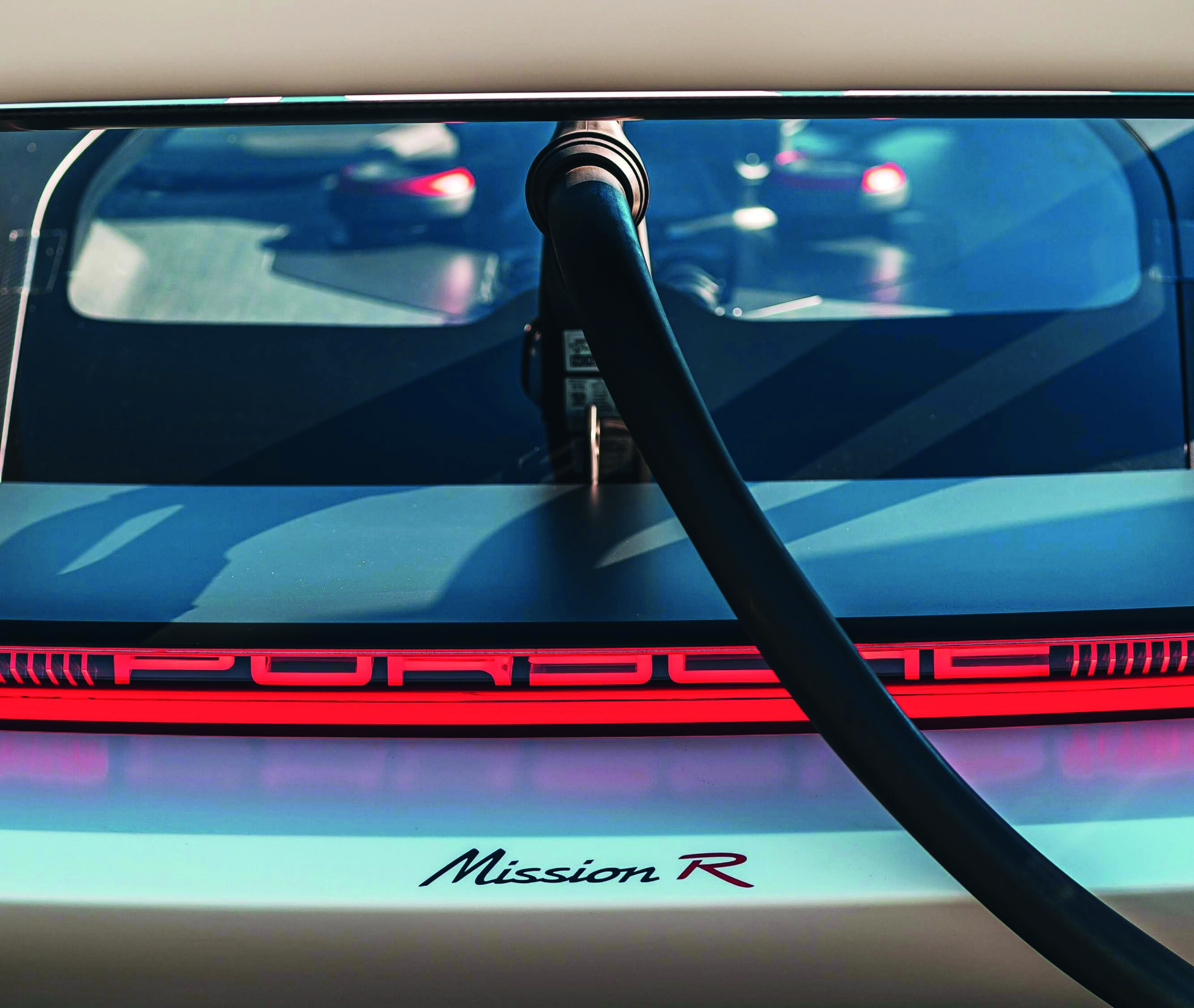

Mission Possible: Porsche's phenomenal electric concept car

Does this phenomenal-looking, electric-powered Porsche concept herald the arrival of a new breed of track cars? Andrew Frankel heads to California to experience the future

The future of Porsche in motor sport is something to behold. It has its Formula E programme and its works RSR team, while customers can buy 911s in RSR, GT3R or Carrera Cup guise, or a Cayman for GT4 racing. For good measure there’s also a GT2 RS Clubsport to race wherever it may be allowed and, of course, its own Esports Supercup series.

But that’s nothing. In 2023 it will return to the top level of sports car racing when it enters the LMDh category of the WEC, and if the mood music emanating from Stuttgart is to be believed, it seems very possible it will be back in Formula 1 in time for the next big rules shake-up in 2026. It can’t do it all. Can it? But as you will note on these pages, its ambitions go further. For what you are looking at is Porsche’s vision of an all-electric customer racing car of the not very distant future.

Which is why this Porsche Mission R, despite being a ‘concept’ car of which just one functioning example will be built, is one of the most important cars in Porsche’s history – and, indeed, the evolution of the sports car.

For while other manufacturers may regularly produce concepts almost for the hell of it – or, more usually, because they don’t want to go to a motor show with nothing new to talk about – Porsche never does. Its concepts always find a way into production. Look, for instance, at its previous ‘Mission’ concept, the Mission E. That was turned with remarkably little alteration into the Taycan which, as I write, is now the UK’s best-selling Porsche.

An RSR steering wheel has been fitted to the car. As a one-off concept there was little point making anything bespoke

So, yes, this is a concept, but so too is it a statement, about an all-electric customer racer of course, but more even than that. Look at it and it’s not hard at all to see an electric Cayman, Boxster or even – dare I say it? – 911 road car too. We know that, probably sooner than later, all these cars will have to go electric and the Mission R is by a distance the best guide yet as to what they will be like.

There’s something else that’s quite different about the Mission R. Most concept cars are mere models, made from clay or wood; those that drive tend to do so only at walking pace and then only so they can be photographed for the accompanying press pack. The Mission R, however, comes accompanied by Lars Kern.

If the name rings a bell it is because he is the engineer-cum-racing driver who puts it all on the line to record Nürburgring times in Porsche’s nuttiest road cars. He is the road car lap record holder with a time of 6min 43.3sec in a 911 GT2 RS MR, which would have been good enough for seventh on the grid behind a bunch of Porsche 956s at the 1983 Nürburgring 1000Kms, the last time the big track was used at the top level of sports car racing.

To keep a low profile, there is no space for battery beneath the driver. A central block battery has been placed where the petrol engine would be

Lars is here because while the Mission R is indeed a concept model, so too is it a fully functioning concept and once he’s shown me how it works, he’s going to get out and let me have a go instead. A proper go that is, on slicks, around the test track at the Porsche Experience Center just outside Los Angeles.

And it is no small undertaking. Even though I am to be denied the full 917/30-equalling 1100bhp it can generate in so-called ‘qualifying’ mode, I’ll still have 670bhp under my right foot, an ocean of torque and all in a car weighing around 1500kg. And with four-wheel drive thanks to its front and rear electric motors, I should be able to use all of it almost all of the time. In simulations, it has returned lap times similar to a 911 Carrera Cup race car.

The Mission R started life as a current Cayman but there’s almost nothing save a small centre section left as it was pushed, pulled, prodded and cajoled into the form you see today. In size terms it’s actually closer to the next Cayman which we will likely see in 2023-24. It bears a closer resemblance to the RSR Le Mans car, whose front suspension, rear axle and sundry other items like its steering wheel it has donated to the Mission R project.

The pre-drive briefing reminded me of one I once received before flying a Hawker Hunter, to wit there was very little about actually operating the thing (you’ll be glad to know I was not alone up there), and a very great deal about how to get out if it all went wrong. And even with the Mission R this was important because there are 900 volts running through the core of this car and if it were to connect to the ground via me, well the results would be none too pretty and probably quite smelly too.

Sadly Porsche opted not to fit the Mission R with a Martin-Baker ejector seat so I have to listen carefully to distinguish between small problems that will just stop the car, bigger problems that will require me to stop the car but under no circumstances attempt to get out of it, and absolutely enormous problems which will require me to perform a ‘KERS jump’, whereby you vacate the vehicle by somehow manoeuvring yourself into a position where you can leap clear of the car without touching the ground, at least until you land some metres yonder. Having seen how difficult it is just to get into the Mission R’s cockpit, I’m rather hoping that rapid aerial dismounts will not be part of today’s activities.

Once I’d done a couple of laps with Lars, during which he put some heat into the Michelins and I remembered how car sick I get in passenger seats on race tracks, it was time to slide myself behind the appallingly complicated RSR wheel and try it for myself. Happily I need just one of its myriad controls, a switch that effectively arms the car for action.

With just nine months to create a fully working concept car, Porsche used the steel body of the Cayman as its basis

And now I must tell you that thanks to Porsche’s understandable desire to be seen to be acting with an abundance of caution when letting a journalist loose in a 900-volt prototype, I am only allowed to admit in public to driving the Mission R at 62mph.

Had I been able to drive it faster – much, much faster in fact – I’d be obliged to come up with some form of weasel words to make it clear that I had done so without actually saying as much. Which is what I appear to have done.

Before you set off, you have to banish all thoughts of this being a concept car from your head. Though that is its purpose, if it is to be understood it is much better thought of as a slicks-and-wings racing prototype. Another thought is its value. Clearly it’s not for sale and therefore has no official price; unofficially however I am told it stands in Porsche’s books at £6.8m. So nervous about it is Porsche that I was told before I got on the plane that if it was raining I wouldn’t be driving, though whether that was through fear of me crashing it or it damaging me through short-circuiting was not made clear. Happily there seems to be more chance of Martians landing than it raining in Southern California these days.

A voice crackles over the line. “Andrew, position one, please.” It belongs to a Porsche employee called Marc Lieb. Yes, that’s the 2016 Le Mans winner. Marc is even more understated than Lars – which is going some – and he now passes his time in the Porsche Motorsport PR department. It provides some indication of just how seriously Porsche takes this stuff.

I flick a switch on the wheel and wait for Marc to get the OK from the backstage battery of people who monitor this car’s every move. It is now armed and ready to go. I’m half expecting him to tell me I’m cleared for take-off but instead he just says, “When you’re ready you can start your laps.”

Gentle pressure on the throttle and the Mission R noses forward. I’d like to say it silently glides, but it doesn’t. Even through the helmet, balaclava and earplugs, it’s remarkably noisy in here: whirrs from the motors, whines from the driveline; it’s not entirely unlike a conventional racing car where the sound of a straight-cut transmission tends to drown most other sound sources.

The Mission R can be rapidly charged – 80% in 15 minutes – and the battery can last for the current length of a Carrera Cup race (30-40 minutes)

And in certain ways, it’s just much easier to drive. Like a 911 Cup car, there are no driver aids of any kind in here, but you don’t have paddles to pull or a torque curve to manage and you can always rely on that driven front axle to haul you out of trouble, something that cannot be said about a Cup car which demands it is driven in a very particular and precise way.

Does that make it boring? Not in the time I was on board. On the contrary, with a new and deceptively technical track to learn and the car’s pulverising power I quite appreciated having the additional brain space to concentrate on nailing my braking points and keeping my lines neat on what is quite a tight track. Also, with monster torque, slicks, wings and four-wheel drive, it comes out of corners like an artillery shell departing the barrel.

It is also very, very clever. For instance, some 40% of its braking is done regeneratively, so without having to use its monster discs

at all, and try as I might I could not feel the switchover point. Also when I mentioned to Lars that the car was understeering on turn in, he pointed out that in a race situation you’d be able to change the car’s set up while you’re driving just by choosing to vary the torque split between the front and rear axles, just as racers today might habitually fiddle with their brake bias.

Of course there is a lot more development work to be done. Right now the Mission R will run flat out for around 30-40 minutes so it’s hardly an endurance racer. Of course it could run longer with bigger batteries but that would add mass and the car is probably already about as heavy as Porsche would like it to be.

What it does do already is give me hope for the future of this kind of racing car. Because when you’re hard on the brakes on your way into a corner, balancing the car through the apex or cannoning away to the exit the sensations experienced and the skills required are no different than with any other racing car. Yes, it reduces your tasks by having linear throttle response and no gearbox to manage, but that is not to say it does it all for you.

Indeed there are plenty of racing cars out there right now with foolproof antilock and traction control systems that take an even greater workload off your hands, just in a different way. And for myself I’ll always prefer a car without driver aids to one that allows you to mash one pedal all the way into the apex and the other all the way out again. Do that in the Mission R and you’d never even get it turned.

Although it’s an EV, the sound from the whirring engine is loud

What can we infer from this car about the future of racing? Well, it’s a new era for sure, but we’ve had those before and the sport has survived. And so far as the alleged lack of involvement is concerned, when you consider all that’s already been lost in the modern sport – the H-pattern gearshift, the heel and toe downchanges, the need to modulate brake pressure and balance the throttle to maintain traction – it’s not that big a step at all.

I don’t know what Porsche is planning to do with the project, but I’d not be amazed if it were developed into a one-make race series to stand alongside (and not instead of) Carrera Cup, not least because sponsors will be looking to maintain their profile in prestigious forms of motor sport while appearing to put their most environmentally friendly foot forwards. The R is not the future of racing but surely it, or cars like it, will form at least part of it. Having experienced it at close quarters, I am surprised how untroubled I am by the prospect.