Mike Spence biography review: A gentleman on and off the track

A first biography for Mike Spence reveals a decent driver with talent but lacking the killer instinct, says Gordon Cruickshank

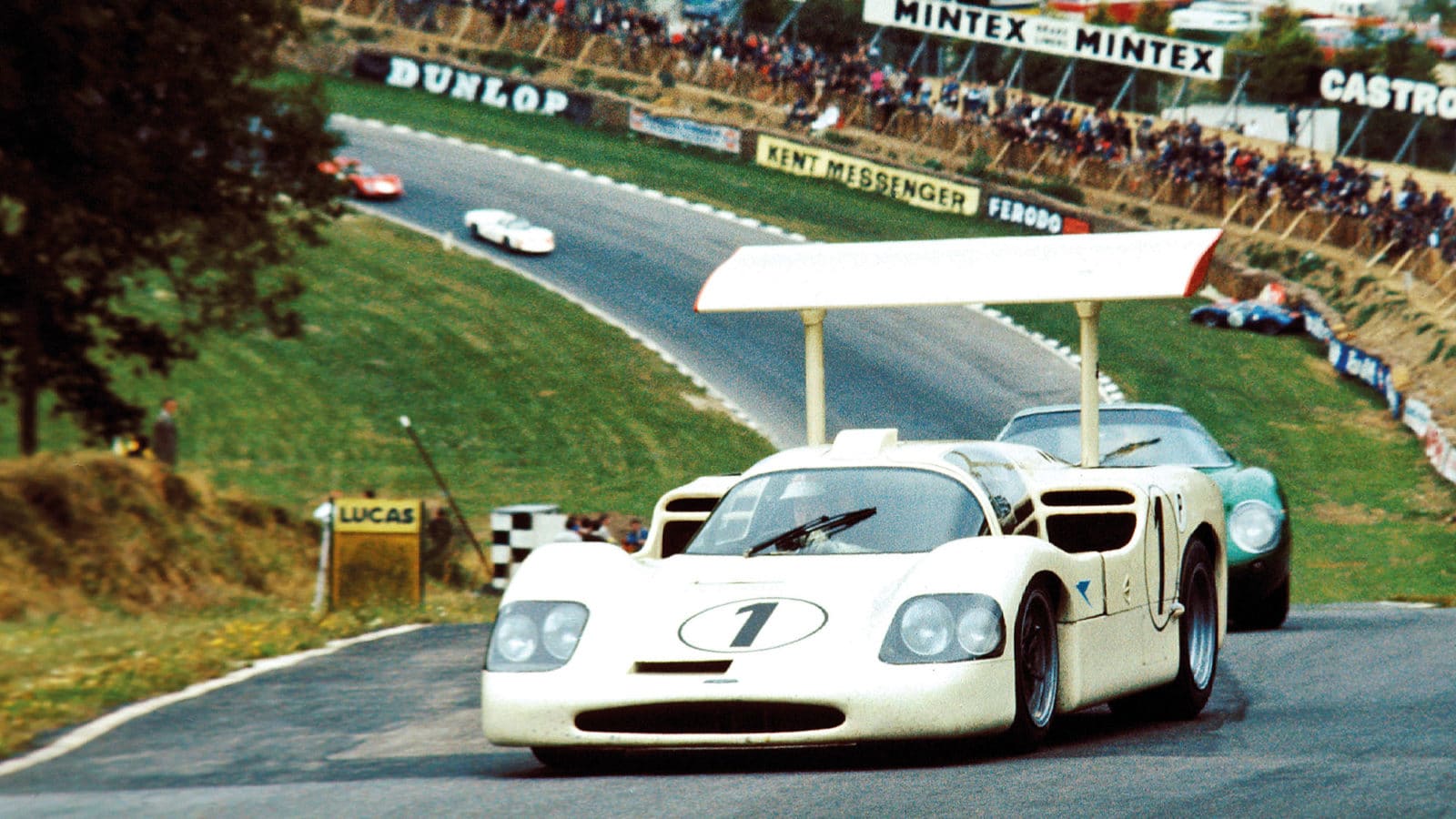

Great white hope: after early frustrations, victory in the Brands 500 with Chaparral was a sweet reward for its drivers and mercurial designers

This is the second time Richard Jenkins has struck a hitherto neglected subject, the driver who oddly hasn’t had a full biography so far. (I can think of one other yet, Richard.) After his award-winning book about Richie Ginther he turns his keyboard towards a British equivalent. Like a powerboat which never quite gets on the plane, Mike Spence’s career nearly took off, but not quite. Despite 37 Formula 1 races he has just a couple of non- championship victories to show. Many people felt it was an unfair record.

Spence tends to show in the records as a supporting player, but as Jackie Stewart’s foreword points out his biggest problem was that he was driving a Lotus alongside Jim Clark. Yet he wasn’t driven to be champion; Jenkins quotes him saying, “I don’t have a deep-seated need to be a racing driver, I just like doing it.” A contrast with something he said in 1968: “Ever since I was a child all I wanted to do was to become a racing driver.” Perhaps the difference is between wanting and needing.

Undoubtedly the great strength of this book is the personal memoirs from those close to him such as his wife and his brother John, whom Jenkins quotes extensively, giving us a very personal view of a young lad from a comfortable background, good at sport but focused on cars. It must have been devastating when in 1942 he contracted polio. As Jenkins points out it’s hard for us to remember the terrible effects – paralysis or disability – this disease had on so many children until it was almost eradicated by widespread vaccination. Spence, though, got through it unaffected.

From merely watching at Goodwood he was soon driving his Riley Imp and then, following national service, decided by 1958 that motor racing was to be his career. Most aspiring drivers would like to have a family like the Spences, who purchased an AC Ace Bristol for him, though he honed his race craft on his dad’s very rapid Turner. When it was time to step up to single-seaters the family clubbed together to buy the components of a Cooper/BMC Formula Junior to be raced under the banner of CERT, for the family Coburn Engineering company. According to Jim Meikle, his cousin and helper, they built it “by guesswork, common sense, and a small cutaway drawing from The Motor”.

Mike Spence: modest, friendly, talented – but too gentlemanly to be a champion?

Jenkins has been lucky that Meikle put a book together in 1962 detailing the early years of CERT, although it’s more family fun than historical record – team manager David Porter describes himself as “a master tactician, second only to Alfred Neubauer, and who wears a similar hat”. The completed car was hauled around in the back of a van with a caravan to live in, Mike proving a steady finisher in a somewhat underpowered car.

But it was in an Emeryson in 1961 that he began to make his mark, winning a 100-mile race and entering non-championship F1 races. Thence via the Ian Walker team he was recruited to the Lotus F2 operation and finally a Lotus F1 seat – where it with his luck to be team-mates with Jim Clark. Though perhaps he was no ‘lost champion’, Jackie Stewart saying, “he was a good driver, not a great driver, and there were a lot of those around”. Good enough to be picked up by Chapman – but the F1 seat disappeared when previous incumbent Peter Arundell recovered from an accident. That was perhaps Spence’s best shot at the big time; switching to Parnell-BRM and then the works team brought no highlights (Tony Rudd said he was too gentlemanly on track), but a call from Jim Hall in 1967 saw him making a big impression in the Chaparral 2F, winning with Phil Hill the BOAC 500. If not for reliability problems we might remember him for more victories in the big white machines. Instead we recall his tragic death qualifying a Lotus 56 turbine car for the 1968 Indy 500.

The simple biographical details, though, are here illuminated by personal memories. Jenkins calls on many sources, whether first- hand interviews with Spence’s wife Lynne and others who knew him well, or from previous interviews. Some are amusing, like the maid who drank all Mike’s prize bottles of champagne, some affecting such as David Hobbs reflecting on the emotional time he spent with Mike at Jim Clark’s funeral, and two weeks later was at Mike’s own obsequies. But if there’s one thing that stands out it’s what a decent guy Mike Spence was. In all the memories Jenkins calls on, from Stewart and Phil Hill to the Lotus mechanics to an Indy spectator who talked with him minutes before the crash, no one has a bad word to say. Words of respect and affection abound for a man who appears approachable, modest, always pleasant, as kind to youthful racing fans in the paddock as he was to his machinery. The Indianapolis Star said in its tribute: “Mike was winning friends as quickly as he was lapping. He had a ready smile and a ready answer for any question.”

This paperback won’t win any design prizes and there are some iffy pictures, but the sheer range of research and interviews is impressive. History may remember Spence as a journeyman, but many of the people Jenkins quotes suggest that he was on the verge of greater things. Either way, I believe I’d like to have known him.

Richard Jenkins

Performance Publishing, £27

ISBN 9780957645097