When Kazuki Nakajima joined Williams in 2008, Frank, eyes twinkling, expressed optimism that he had the right attitude. “On his debut, in Brazil [in the final race of 2007], he came into the pits a bit too quickly, and knocked down one of the mechanics. Later he set the fifth-fastest lap – and never once got on the radio to ask if he’d hurt anyone. I thought that was a bloody good sign!”

Back to Jones, and the end of a Williams era. When Alan decided to retire at the end of 1981, informing his boss at Monza, very late in the day to find a top-level replacement, Frank didn’t hide his displeasure when I visited him just before Christmas.

“I don’t think Alan’s late decision was deliberate – it’s just that he’s a very inconsiderate person. You have to be realistic about drivers, to accept that most of them are in it to make as much money as they can – and as soon as they’re satisfied… gone, right? We’ve had problems with him and Carlos (Reutemann) this year, and to be honest I just found that very boring. They’re only employees, after all. All I care about is Williams Grand Prix Engineering, and the points we earn – don’t give a toss who scores them…”

Even in the old days, you didn’t get quotes like that from other team owners. No surprise that we loved the Williams team like no

other. When flashy new car launches were fashionable, it was always the trip to Didcot that we anticipated with most pleasure, because the ambience would be informal, because Frank and Patrick treated us like friends, and had the confidence to be honest. Dry wit counted for rather more than dry ice. Then they’d go off and win the first race.

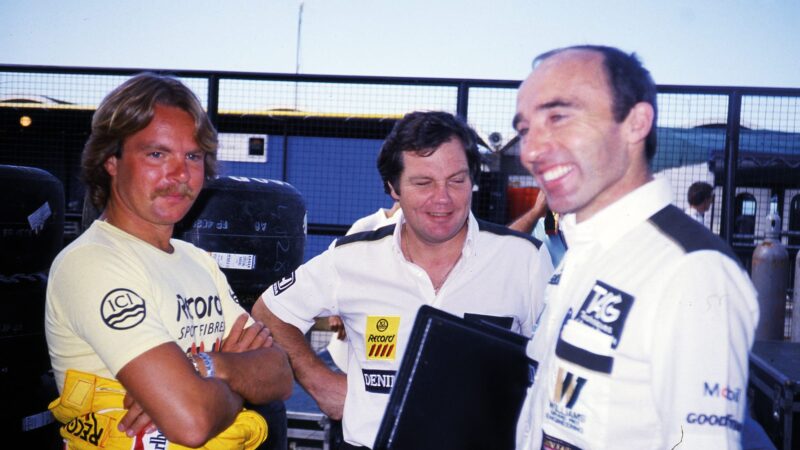

Keke Rosberg was Williams’ second world champion

Williams Racing

For all his saying that they were ‘only employees’, Williams always had a reverence for racing drivers, in particular those who were natural chargers – Jones, Keke Rosberg, Nigel Mansell, Juan Pablo Montoya, overwhelmingly Ayrton Senna.

“That was something I shared with Enzo Ferrari,” Frank said. “I never admired him, as such, because he had such a disruptive influence on motor racing, but I deeply admired his success. The only other thing we had in common was our esteem for Margaret Thatcher – Enzo told me how he wished she could rule Italy.” A framed photograph of Maggie hung on the wall in Frank’s office: “The last politician who said what she was going to do, and did it.”

“Ayrton came to Williams and in three races everything crumbled”

If Williams and Head – ‘Frank and Patrick’, as they were in the paddock – remembered the Jones era as their favourite time, it was merely the beginning of a long period in which the team was at the forefront of F1, invariably competitive, sometimes dominant. Rosberg was their second world champion, in 1982, followed over time by Piquet, Mansell, Alain Prost, Damon Hill and Jacques Villeneuve.

Relationships within the team were sometimes difficult: “If I think back to 1987, when we had Mansell and Piquet,” said Williams, “we’d finish 1-2, and the loudest noise afterwards would be the moaning of the guy who’d finished second…”

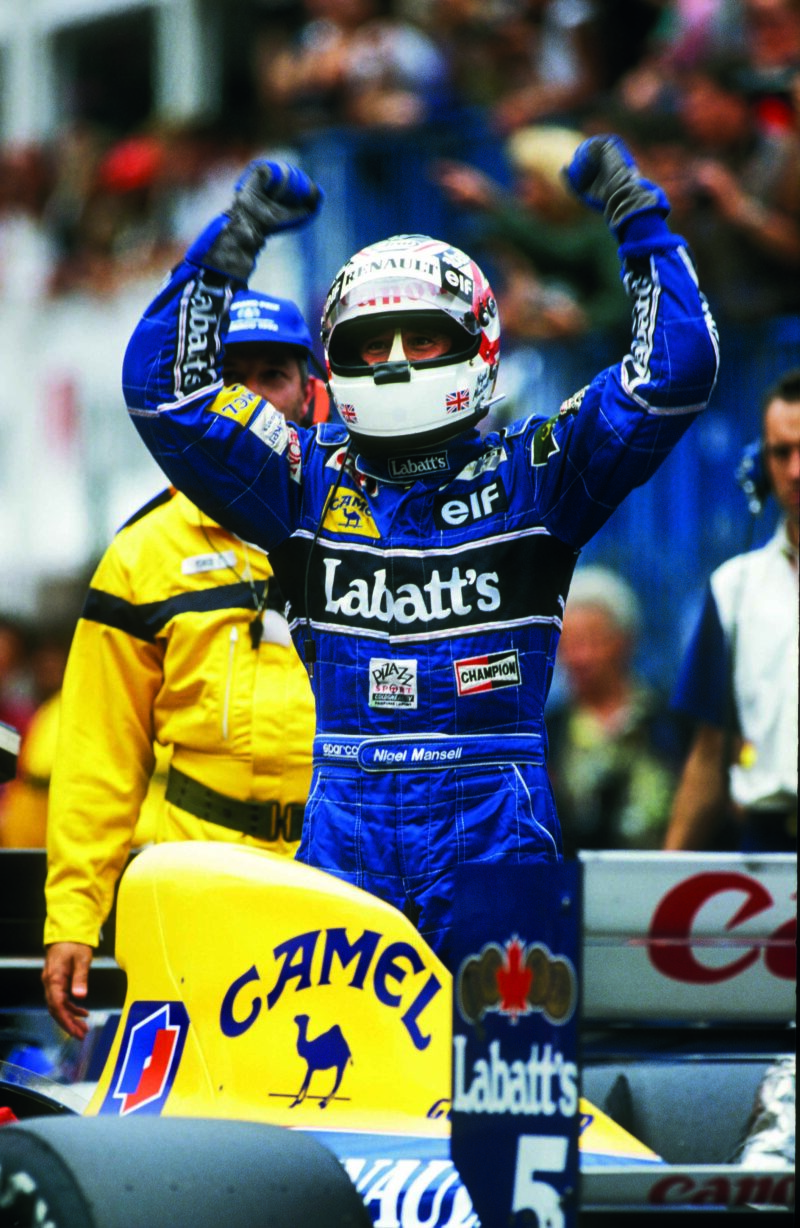

Nigel Mansell is delighted with his pole at Monaco in ’92 – a golden season for Williams with Mansell the title winner and Patrese runner-up

Grand Prix Photo

Occasionally, too, decisions taken – notably to fire Hill at the end of 1996 – were not easy to fathom. “Damon disappointed us in ’95, and that was when we decided that, at the end of his contract, we would go with Heinz-Harald Frentzen instead. As it was, Damon transformed himself in ’96 and won the championship, after which we got nowhere with Frentzen! Not our shining hour…”

Overwhelmingly, of course, the low point in the team’s history came at Imola in 1994, when Ayrton Senna was killed.

It was in a Williams, at Donington 11 years earlier, that Senna first experienced a Formula 1 car, and from the first Frank was a committed fan.

“I should have signed Ayrton on the spot, but at the time we were pretty embedded in a policy of going only for experienced drivers. As soon as he was into F1, though, I regretted that I hadn’t taken him – it was obvious he was something very special.”

Ayrton Senna joined Williams in 1994 as team-mate to Damon Hill

Alamy

Over time the two men kept in contact. “Sometimes it was twice a week, sometimes a couple of months apart, but we never lost touch. Ayrton just loved to talk motor racing – get him on the phone, and you couldn’t get him off it. I used to love those chats, and I was thrilled when he eventually agreed to join us.

“We had a difficult car at the beginning of 1994, and yet he was on pole position at each of his three races. Quite remarkable. Everyone in the company was truly shattered by what happened at Imola. At the end of the day the fact is that Ayrton Senna died in a Williams car, and that’s an enormously important responsibility. Quite apart from anything else, I feel embarrassed that Ayrton never got a fair crack of the whip at Williams. He’d come from McLaren, after six years… brilliant career there, massive achievement… came here, and in three races everything crumbled…”

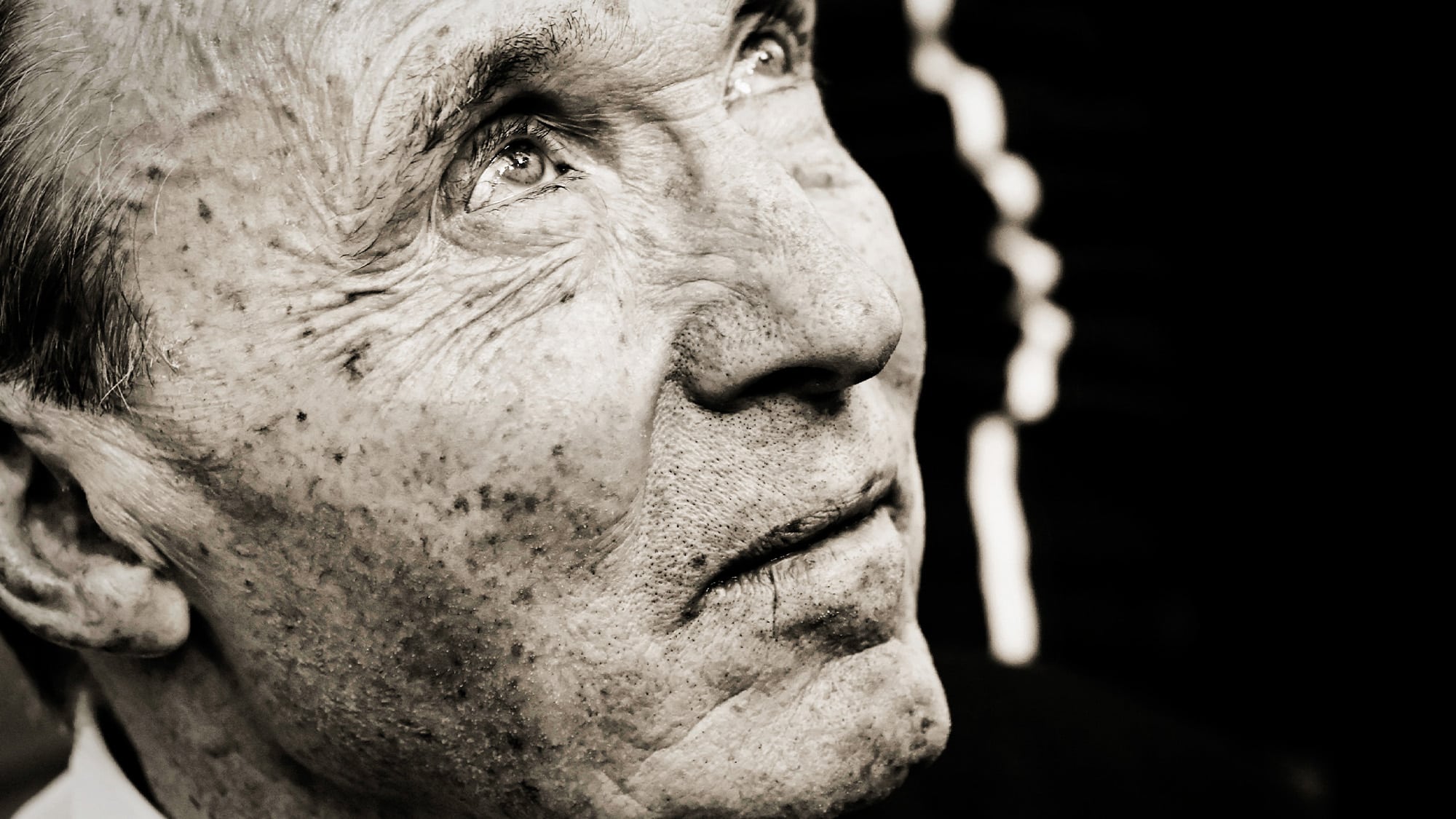

Never a man to spare himself, Frank Williams. How, I wondered, had he contrived to focus on the fact that, whatever else, Monaco was only a few days’ hence?

“It comes naturally, I suppose. Ayrton was clever, shrewd, focused, tough – all the things I admired – and, as with Piers, I remember

a great sadness, but I don’t remember any particular difficulty in going to work, or turning up at Monaco. You’ve got to do it.”

And do it he always did. Williams lived Formula 1, and that never changed, even when his team’s great years were long in the past. After Montoya’s victory at Interlagos in 2004, eight years would go by before Pastor Maldonado put another on the board at Barcelona, the last race attended by Frank’s beloved wife, Ginny, who died of cancer in 2013. Without her, he always said, he would never have made it.

Over time the state of his health kept him from going to the races, so that his occasional appearance in a paddock was greeted with pleasure by all those who loved him. Frank Williams had a greater passion for Formula 1 than anyone else I have known, as I remember from all those Sunday phone calls, when he – of course – was in the factory, and just wanted to talk racing. “The perfect Formula 1 car? Easy – 1000 horsepower, and no downforce!” There was no one like him, nor ever will be.