F1: The Strange 2020 Season

Just like a well-scripted television drama, Formula 1 has given us crises, cliffhangers and much-needed escapism in this virus-shackled year. From the dominance of Mercedes to Grosjean’s incredible escape and Russell’s rotten luck, Mark Hughes looks back at the season that almost never was

The world became very strange this year, didn’t it? It was just beginning to go wobbly as F1 prepared to head off to Melbourne in March. For a race that never happened, fans queued up at gates that would never open as the organisers and F1 engaged in a game of stand-off about who exactly would be calling the event off after a confirmed Covid case from within a team – for that call had big financial implications.

Those consequences would run far wider and deeper than just that race, of course. Everyone went home and lay low in the dark days of the first wave of the pandemic and the originally scheduled calendar fell like a house of cards. The factory shutdowns were brought forward from summer, redundancies were made – and nothing was certain. Not even if there would be a season at all or whether all the teams could survive, starved of income.

But Formula 1 is like a virus itself. It quickly mutated a way to have a season. Liberty Media – after refinancing itself from its parent company – showed extraordinary resolve and creativity in making it happen, driven of course by the economically terrifying prospects of not doing so.

Needs must, and in creating a 17-race global calendar in the middle of a pandemic, the whole economic model of the sport was turned on its head. In order to meet the pay-out terms of the TV contracts, a minimum number of races had to happen. But with the venues not able to host spectators, most – but not all – of them were in no position to pay for their races. Formula 1 instead effectively rented the tracks from them for a series of TV-only events. With an entire leg of its economic model removed, and Covid always liable to close the whole operation at any given moment, it was a hairy old flying-by-the-seat-of-the-pants season for the business.

This season Lewis Hamilton made himself heard both on the track and off it, breaking records whilst spreading the message of the drive for racial equality

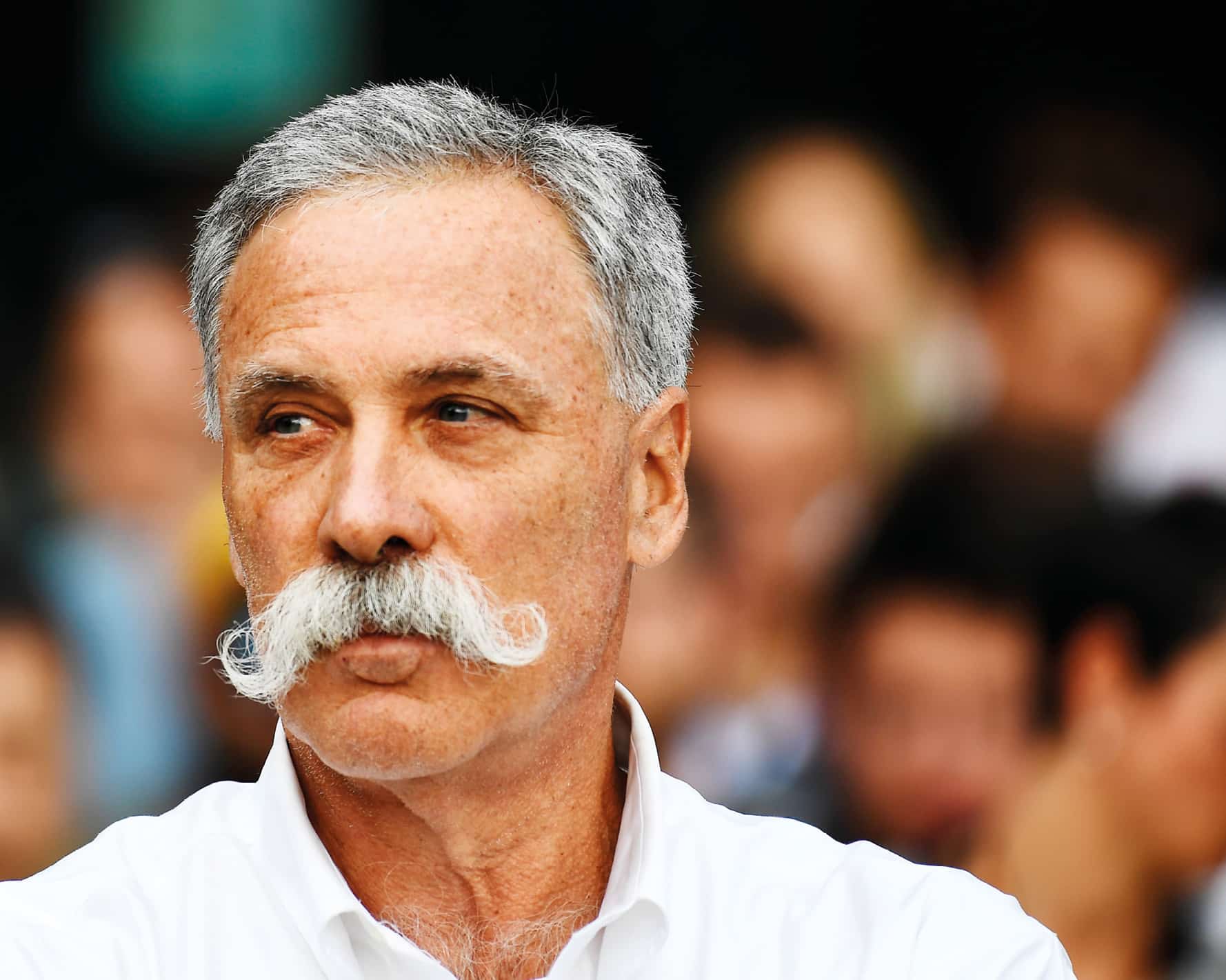

Liberty’s Chase Carey, who retired from his role of CEO of F1 at the end of the season, has to be given great credit for navigating a route through the storm while simultaneously getting a new Concorde Agreement set out and within a cost cap, a concept F1 had been trying but failing to embrace for over a decade. Meantime, the all-new aero regs scheduled for ’21 were postponed for a year and cost-saving measures were imposed that prevented the teams creating new monocoque designs, together with other specification freezes. There was a certain element of shock doctrine enabling Liberty to make changes that some of the top teams had resisted and blocked for so long.

World events had an air of TV drama unreality, and F1 played its part. The sport’s most famous exponent laid waste to the season on track, breaking the all-time record of career success into the bargain. As the championship’s only black man, troubling scenes in the bigger world led Hamilton to step up his campaigning role for diversity and equality – and the sport was obliged to follow him. How could it not? With long-accepted norms being challenged everywhere within a world that had changed faster and more profoundly than in anyone’s living memory, how could F1 be seen not to agree with its poster boy as he used F1’s platform to right wrongs? He made it choose a side. He’s transcended F1, and his new status as the most successful driver of all time just rubber-stamped his credentials.

Then, what would be the obvious twist to such a narrative if it were indeed a TV blockbuster? The champion himself would contract the virus, wouldn’t he? Soon after breaking the records. And standing in for him would be a young unknown, thrown into the spotlight – and so George Russell, in Hamilton’s car, created a sensation at the penultimate race. The double-twist of his apparently nailed-on victory being subverted by a radio problem in the pits seemed an over-the-top flourish of the scriptwriter’s imagination, though. The story could have benefited from a good editor.

George Russell steps in for Hamilton

Within the main story treatment there were subplots and mini-dramas. An important backstory thread was that of Ferrari, the sport’s most famous team, having its wings clipped by the governing body before the season even began.

“After thorough technical investigations, the FIA has concluded its analysis of the operation of the [2019] Scuderia Ferrari Formula 1 power unit and reached a settlement with the team,” read an FIA statement in February. “The specifics of the agreement will remain between the parties.

“The FIA and Scuderia Ferrari have agreed to a number of technical commitments that will improve the monitoring of all Formula 1 power units for forthcoming championship seasons as well as assist the FIA in other regulatory duties in Formula 1 and in its research activities on carbon emissions and sustainable fuels.”

Sebastian Vettel off at Monza

This was dynamite. It stopped short – but only just – of accusing Ferrari of having cheated the fuel flow regulations to gain an illegal power advantage in 2019. The FIA and Ferrari clearly had each other by the tender parts, with the governing body having uncovered – with a bit of guidance from rivals, no doubt – strong circumstantial evidence of wrongdoing. But there was no proof of the systems having been used (much like Benetton’s launch control of ’94) and Ferrari was doubtless prepared to go legal if the FIA tried to apply penalties for an unproven offence. Hence the compromise of a ‘private agreement’, which was FIA president Jean Todt’s way of pointing out in neon the reality below the surface of the statement. Far from being a Ferrari-favourable ruling, the whole investigation had been initiated by the governing body. Todt followed up by saying he would be happy to go public with what the agreement was – but that would of course require Ferrari’s consent as the other party to the agreement. That agreement wasn’t forthcoming. All the dots were joined, apart from the very last one but even that was being pencilled-in by the FIA. The picture was clear.

New technical directives were put in place to ensure the Ferrari interpretation would no longer fly. Ferrari lost in the region of 65 horsepower from the previous year. Mercedes, having been stung into extraordinary development efforts by the Ferrari power advantage of the previous season, increased its horsepower for the new season despite the greater engine restrictions. Thereby was laid the foundation for a season of dominance extreme even by its standards.

Its qualifying advantage over the next-fastest car – the Red Bull-Honda – was around 0.7sec (up from 0.13sec in 2019). Meanwhile Ferrari, the team which had started from pole nine times in 2019, sank to midfield obscurity… In the midst of all that, before the season had started, Ferrari boss Mattia Binotto had made the difficult phone call to his four-time world champion Sebastian Vettel to tell him there would be no place for him at the Scuderia next year. It was all couched very diplomatically in the subsequent release, implying that they had been unable to come to an agreement. “No,” corrected Vettel at the first race. “There was no offer to agree to.”

Tough decisions for Chase Carey at the Australian GP in March

If there was an upside for F1 about the horrible pandemic, it was the collection of tracks upon which the championship was fought. We lost some great venues (notably Montreal and Austin) and lost some big payers (China and Singapore). We lost what was going to be Vietnam’s first grand prix (and now we probably won’t ever see it). But the return to the Nürburgring and Imola carried a lovely retro vibe and it was great to see Istanbul again – while the addition of Portimão and Mugello were wonderful. Combine these with a core of traditional hosts – the Red Bull Ring, Hungary, Silverstone, Spa, Monza, Bahrain, Abu Dhabi – and we enjoyed an interesting and varied quick-fire calendar. And boy was it quick-fire: four triple-headers amid 17 races in 23 weeks was a brutal schedule for all those involved.

Mercedes set the tone of its season by locking out the front row of the opening race, in Austria. Valtteri Bottas was aided a little by a couple of Hamilton penalties – one in qualifying and another in the race – but nonetheless got his quest to finally beat Hamilton over a season off to a great start with a very composed win.

But in the following 16 races he would win only once more as Hamilton simply steamrollered him to an extent even beyond anything he’d managed before. There was something about the Mercedes W11’s traits that seemed to allow Hamilton access to some very special places. A week after that season-opener, the same venue hosted a wet qualifying for the Styrian Grand Prix. It was one of the most exciting Saturdays of all time – and finished up with Hamilton on pole by a resounding 1.2sec. His incredible performance was described as ‘otherworldly’ by his employer Toto Wolff.

A return to Imola in November sunshine for the Emilia Romagna Grand Prix, and Italy’s third GP of the season. This is Bottas in practice

In Spain, for round six, he spent the entire race with the heat-degrading tyres right on the cusp as he put half a minute on the field. He afterwards described himself as having been in some special zone. His Schumacher-beating 92nd grand prix victory came at the Nürburgring and it was a genuinely moving moment when Mick Schumacher shyly sidled alongside him and handed him one of Michael’s helmets.

In Turkey he was stunning on race day on the low-grip cold track, waiting an age for his tyres to reach temperature – and only then hunting down the cars which had qualified ahead of the Merc on a day when it was 5sec off the qualifying pace because of the weird conditions. He won that one by half a minute too. Bottas spun many times in a damaged car and Hamilton had to negotiate him while lapping him. Only when penalised – in Austria, Monza and Sochi – was he properly beaten. There was the 70th Anniversary Grand Prix at Silverstone where Mercedes had got the set-up wrong for the very soft tyres – and with severe blistering it could offer nothing against Verstappen’s Red Bull. But that was it. Barring mishaps, Hamilton won.

The 70th Anniversary Grand Prix was the last part of Silverstone’s first ever F1 double-header

The last victorious race before Covid struck him was Bahrain. But the race won’t be remembered for that. Romain Grosjean’s F1 career was brought to a close two races early after suffering quite the most terrifying-looking accident since the most gruesome days of the 1970s. It was as if that rogue scriptwriter had been let loose again and had got the props department to make a car explode on impact, not realising that such things hadn’t happened in F1 for 40 years or more. It was a horrific impact with a three-layer metal barrier, the Haas piercing it after hitting at 137mph. At that speed, the cockpit halo cut through the barrier like a knife, creating Romain’s first survival. His second came as he somehow managed to find the gap through which to climb from the fireball when all around him was orange and melting. He’d been in there for 28sec. Thank God, we’ve only lost him to F1. For 28sec it looked like we’d lost him.

That was just one of three remarkable happy endings. The others came with victories for the AlphaTauri and Racing Point teams at Monza and Sakhir respectively. Pierre Gasly gave the former Toro Rosso team its second win in 12 years at the same venue as Sebastian Vettel’s first. He brilliantly capitalised on a stop-go penalty for Hamilton after Mercedes hadn’t realised the pitlane was closed when it pitted him under a safety car. Luck – and passing Lance Stroll’s Racing Point – had put him in the lead but he was magnificent in wringing the neck of that opportunity by fending off Carlos Sainz’s McLaren.

A career-first win for Sergio Pérez at the Sakhir GP

At Sakhir – the race around the outer perimeter of the Bahrain track, with a sub one-minute lap – Hamilton’s stand-in George Russell, who has spent his first two F1 seasons towards the back with Williams, was quite sensational but ultimately unrewarded. The recipient of his ill luck – as a radio problem in the garage led to Russell being fitted with the tyres of Bottas (for which you can be disqualified), necessitating a corrective stop – was Pérez. At the 190th time of asking Pérez had finally won a grand prix, and a richly deserved victory at that. The irony, of course, was that he’d been dropped for ’21 by Lawrence Stroll to make way for Sebastian Vettel as the team transitions to Aston Martin. The German had endured an awful season, Pérez a brilliant one – and yet it looked like this could be the end of the popular Mexican’s career. There was just one hope left for him – the second Red Bull seat.

Being measured against the phenomenon that is Max Verstappen is always going to be tough. Doing it in a very demanding car that needs to be constantly ‘hustled and caught’ because of a basic aero flaw is doubly so. Doing it in just your second season of F1, it begins to take on nightmarish proportions. That’s how it was for Alex Albon. There was a will from the owners of the team to retain him despite his pace deficit to Verstappen – at over 0.5sec in qualifying it was the biggest gap between team-mates – and regular incidents. He might have won the first race, having got lucky with the safety car. But trying for an outside pass on Hamilton spun him out. He never looked so competitive again, though he did take a couple of podiums. Too often he was being beaten by slower cars and never at any point was he close enough to be used tactically in support of Verstappen. Pérez won the Sakhir race after being spun to the back on the first lap. One of those he passed and left behind was Albon.

Qualifying for the Styrian Grand Prix in July was a sodden affair, but gave Hamilton a chance to shine in what was an absorbing session

The Racing Point was decent, but it should not have been able to do that to a Red Bull… The fact that the Racing Point was a good car was an issue of some considerable vexation, for it was a clone of last year’s Mercedes. This outraged teams such as McLaren and Renault, the outfits with which Racing Point fought for third in the constructors’ championship. But no-one could prove there had been any information transfer from Mercedes in the car’s creation. Therefore it was legal – apart from an arcane detail about how the rear brake ducts had been created. The rules were changed as a result – but starting next year. It was an effective shortcut in boosting Racing Point’s transition to a serious player and very much in keeping with the take-no-prisoners attitude of its owner, whose son Lance showed considerable progress through the year, as evidenced by a beautiful pole position in the cold of Istanbul.

Other mini-plots included Daniel Ricciardo’s sometimes searing performances in an improved Renault, Carlos Sainz’s signing by Ferrari as Vettel’s replacement and him being replaced at McLaren, in turn, by Ricciardo. And the announcement of the future return of Fernando Alonso to replace Ricciardo. The script really was running wild.

In Abu Dhabi for the season finale Russell’s ‘63’ was peeled back off the nose of the black Mercedes and replaced with ‘44’. And just like that, Lewis Hamilton, after a nasty bout with the virus, prepared to take up where he left off, but he’d still not signed a contract for 2021 – and we were left waiting with bated breath for season two.