About Vanden Plas

Henri Vanden Plas, Coachbuilder of Brussels, was the Pininfarina of the period 1900-1914, and was famous throughout the Continent of Europe for his beautifully designed bodies on Continental makes of…

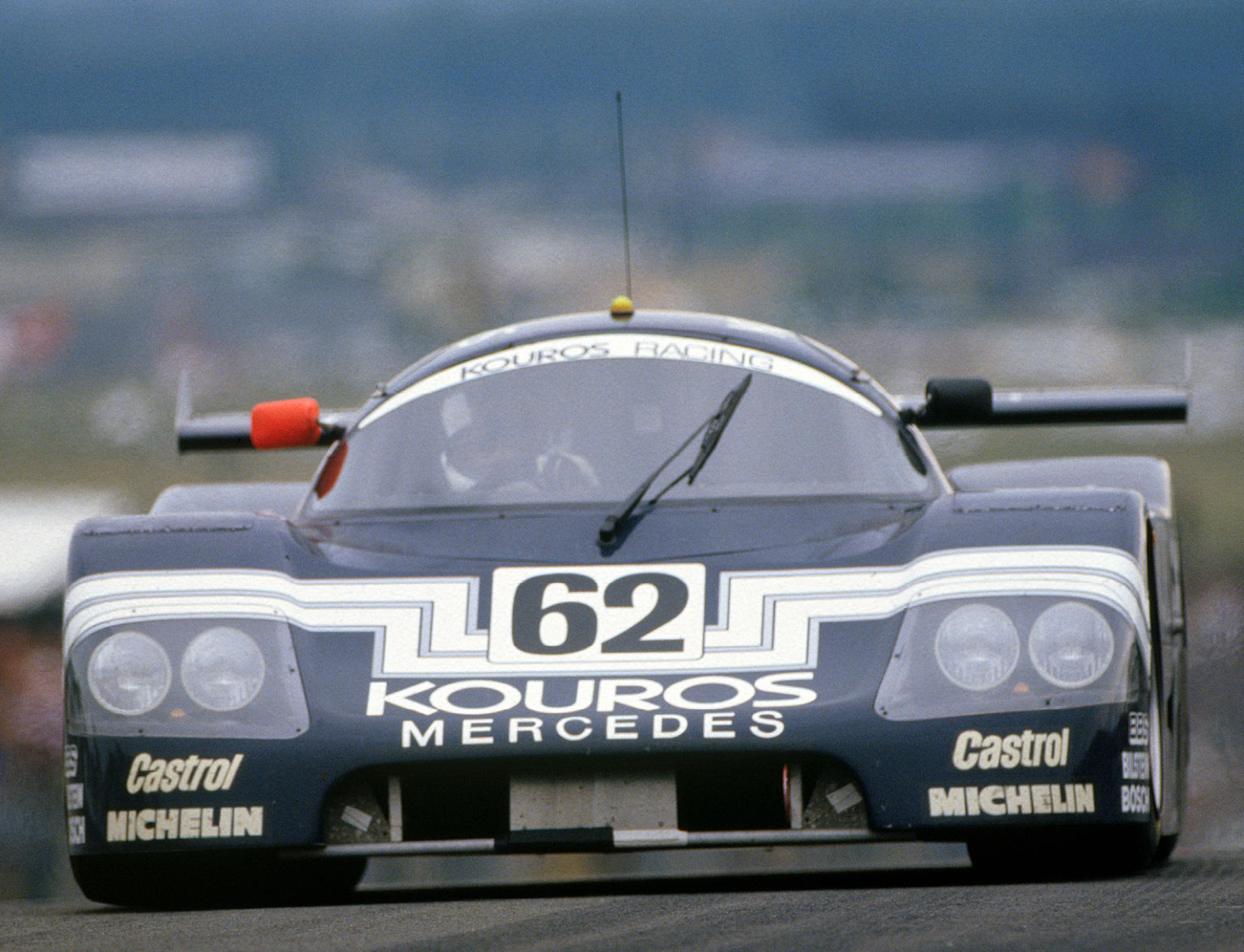

Mike Thackwell and sister Lisa came to Britain from Australia, the children of a Kiwi Speedway rider. Lisa raced in the Renault 5 Cup and Ford Fiestas before marrying David Brabham. Mike’s career trajectory was different. Hailed as a wunderkind, he made the first of his two Formula 1 starts aged 19 for Tyrrell in 1980. He won F2 in 1984. He’s also been a winner in the 1000km Nürburgring. Mike turned his back on the sport in 1988 and has been regarded as one of racing’s great lost talents ever since. Today, he lives simply in a static caravan on England’s

south coast.

Interviews by James Mills

Lisa Brabham (née Thackwell): “I left for England when I was 11, in 1976, long before Mike. Mum told my sister and I that we were off to see our grandparents for a three-week holiday. We arrived, and the next minute we were staying. Michael turned up in late ’76.

I still don’t know to this day whether my parents had planned to not come back, whether Dad had thought, ‘Michael’s bloody good, I’d better take him to England.’ I wasn’t very happy about it. I didn’t like England, to be honest, I didn’t want to stay here. I had left my friends; literally, I skipped out of school and said to them, ‘See you in three weeks!’ and it didn’t happen.

So I didn’t enjoy the rest of my schooling as a result but what do you do, ring Childline?

Dad [Ray Thackwell, a successful international speedway rider] came to England when he was 16, but I can’t remember whether he was with Barry Briggs and Ronnie Moore at that point. He went on to work as a pilot, a car dealer, a gold miner; he just loved the challenge of something that may or may not work. I’d annoy my brothers [Mike and elder brother Kerry] terribly because I insisted on playing their games. If they were playing cricket, I wanted to play cricket; if they had friends round to be in the pool, I wanted to be in the pool.

By the time I was 21, Dad was doing a lot of business with German luxury cars and we had good friends over there that he worked with. They suggested I have a go at the Renault 5 Cup, so I said, ‘Why not?’

Michael was at my first test and I had an instructor, and it was just the best. The thrill, the adrenaline, going fast… I liked it.

“Mum never went to watch Michael race. She didn’t really want him to”

So I did a season in the Renault 5 Cup, and then switched to the Honda CRX Challenge, with Edenbridge Racing and Andy Ackerley and Patrick Watts as team-mates. It was a very, very competitive series but I managed to claim a pole position.

Mum never went to watch Michael race. She didn’t really want him to; I think she would have preferred it if he’d been a doctor. Interestingly, we have a great big photo album that’s full of photos of Dad and Michael, and in the back there are all these newspaper and magazine cuttings with her handwriting on. So she was very proud of him. She always said to me, ‘Watching your husband race is easy. Watching your child race is a nightmare’ and I used to think ‘Stupid woman!’ but now I appreciate she’s absolutely right.

I don’t have heroes, but the more I got to know the Brabham family, I recognised what drivers of Jack’s era did. Whether you believe he is one of the greatest F1 drivers or not, what he did was exceptional. When I met them the person that scared me most was Betty. She was protective and quite intimidating for such a tiny lady.

Racing has changed so much. I don’t like a lot of what I see anymore. However, it is still our industry, our family industry, so you have to roll with the punches. For my son, Sam [who races in the Porsche Carrera Cup], sports car racing could be a career path; he’s a new generation of upbeat person who doesn’t see the decline some of us do, but would I like him to have a different career? Yes, I would.”

Mike Thackwell: “When you’re heavily into something – sport or any career – and you want to get away from it, for whatever reason, you need to chop it off completely. You can’t be part in and part out – otherwise you will never leave. I have felt really guilty about leaving racing at times. I recognise that I was privileged compared to some people and I may come across as rude, but equally I wanted to get away from motor racing.

It was the vanity, self-obsession, elitism and the lack of humbleness that drove me from the sport, but that’s me, it was my problem because I couldn’t deal with that.

Compare the way Moss and Jenks won the Mille Miglia. They crossed the finish line and simply raised a hand. They didn’t jump and do somersaults and beat their chest; I find that really disturbing when there’s no humility in victory, but that’s me, I’m from an older generation.

I’ve been privileged, and I didn’t do it on my own. I was really good at times, but I wasn’t good enough to be a top driver and I thought, I’ve done all these things around the world in the last 10 years, driven all these cars and sometimes for no money, even when I was Formula 2 champion – no money even for testing F1 cars, sometimes – but that was my choice. I just wanted to do it for fun.

In that respect I was quite lucky because I could jump from an F1 car to F3 or Group C to an Atlantic car in New Zealand, and it was great fun. The privilege of doing it like that is you don’t let anyone have a hold over you, and I was lucky enough to have people like Ron Tauranac who let me do what I like.

When I look back, I was awful, self-obsessed. I was wrapped up in me, playing sport, exploring the outdoors, surfing. I’ve forgiven myself for being an arrogant s**t, and I’m content that my son is a better bloke than I ever was.

Other times I came close to losing it all. Just as I was starting to win races, against more experienced drivers, March were going to throw me out because I didn’t have any money

I passed my driving test at 15, because nobody asked any questions back then. Then a chap that Ray had taught to fly, who built Formula Ford cars, put me in touch with the Scorpion Racing Drivers School at Thruxton. That’s where I met gifted drivers like James Weaver, a gentleman who could do anything when it came to building and preparing a car. I had no fear then. Even though there were plenty of crashes where I should have had my head off! But that’s just fate, pure luck. I’ve seen people break their necks at 30 miles an hour!

Other times I came close to losing it all. Just as I was starting to win races, against more experienced drivers, March were going to throw me out because I didn’t have any money. Alan Jones knew that was crazy so he put his hand in his pocket so I could keep driving. I did pay him back, eventually.

I turned down a drive with Ensign, after Clay Regazzoni had his big accident, preferring to wait for the right car, which was the Tyrrell, later that year [1980].

It was during a Group C sprint race, for Sauber at the Noris Ring, that I decided I’d had enough. I was running around and the brakes had gone and the seat was playing up, but it wasn’t that. I went off in the lead and found myself thinking about whether I wanted to be doing this for the next 20 years. I pulled into the pits and said, ‘That’s it.’

Finally, I gave everything away – all my material possessions, including my car and even my cherished motorbike

When I walked away, I got into teaching. I knew I wanted to do something more meaningful, so together with my then wife, Birgit van Ommen, founded the International School of Monaco. But she was from a motor racing family, [her uncle is Armin Hahne; Mike met Birgit when she was an interpreter for the head of R&D at Ford, which came about after Steve Soper offered him a drive in a Sierra Cosworth touring car] and also worked with Bernie Ecclestone and ran the F1 Paddock Club. So I couldn’t get away from the sport and eventually our marriage ended.

Then came all sorts of jobs, from flying helicopters to North Sea oil rigs to helping my old man mine gold, back home in Australia. Finally, I gave everything away – all my material possessions, including my car and even my cherished motorbike – and went to work as a pot-washer in a soup kitchen.

Now I live by the coast, in a 25 by 10ft caravan. I surf, kayak, work in the service industry on a basic minimum wage and look after my mentally handicapped son.

Very infrequently, I might just bump into some of the old faces, like Martin Brundle and JP [Jonathan Palmer]. I hadn’t seen those guys for 20 or 30 years, then saw them at the Grand Prix Trust and it was like I’d just left them. We talked about all the stupid, crazy things we used to do in those days and that was lovely for me, because I haven’t moved on like they have in the sport and they were still the same blokes that I used to know.

What bugs me about the generational thing is how people idolise the so-called glory days. I hate it when we get the old boys going on ‘It was better in our day’. It was exactly the same. It’s just different.

I rarely see my sister. They live in their world and I live in mine. Lisa asked me to take Sam to a kart race once. Sam was a young kid and it was a nice moment for me to have him in the car without his parents, you know. And it was nice to go and look at a kart track. I said to Sam, ‘Don’t try to be fast. Let it flow and you’ll get into a rhythm and all of a sudden your time will start to come down.’

I always say that the greatest fear in life is fear itself. If you don’t give something a try you don’t make mistakes. Your mistakes are your life. Bad things will happen whether you like it or not. So accept that and don’t be afraid because otherwise you’ll never live.”

Follow James on Twitter @squarejames