Lunch with Dick Bennetts

He turned down an opportunity to work for McLaren in Formula 1 and has never graced the sport's top table, but that's no barrier to a distinguished career

For more than three decades he has been a familiar face at UK circuits, engineer and mentor to such as Ayrton Senna, Mika Häkkinen and Rubens Barrichello and more recently the linchpin behind a string of British Touring Car Championship successes. Dick Bennetts first came to England in 1972, to help New Zealand racing buddy David Oxton, and didn’t plan to stay more than a couple of years, but almost half a century has since passed and he’s still here, competing on his own terms. For somebody who originally harboured dreams of a career in architecture, he has achieved an enormous amount in motor racing.

To obtain the full story we convene at The Queen’s Head in Weybridge, Surrey, where Dick, 71, orders gammon steak with egg and chips, takes a sip of still water and winds the clock back to 1950s Dunedin, on New Zealand’s South Island.

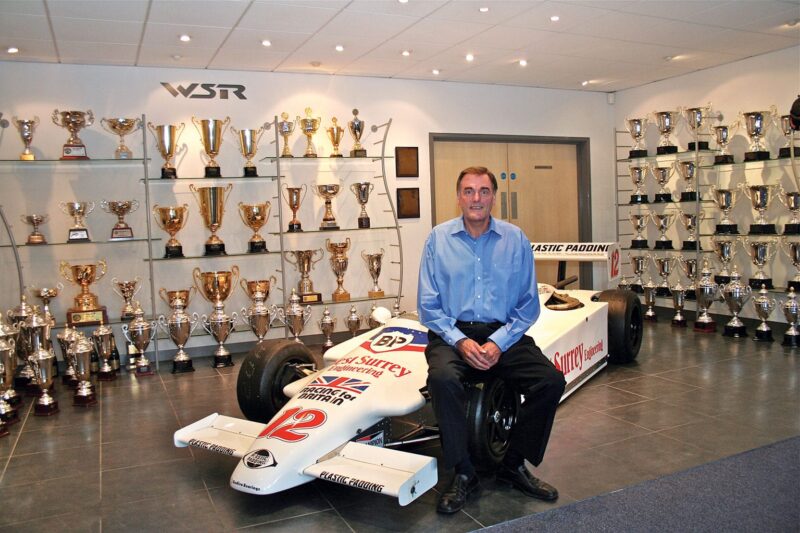

Bennetts was instrumental in the early career of many drivers, here with Senna in British F3, 1983

Motorsport Images

“The family had no real connection with motor sport,” he says, “but Dad took me to watch racing on the Dunedin street circuit when I was about 10, which sparked an interest. As I was growing up my main ambition was to become an architect, but when I got to high school… lazy isn’t the right word, but I didn’t focus enough. My parents never had much money and wouldn’t let me go back for a second year to complete my certificate, so I didn’t have the qualifications I needed to pursue my primary goal. That was a bit of a wake-up call, but my second love was engineering. I managed to land a job with a local automotive engineering firm and quickly took an interest in modifying road cars, starting with my own E93A Ford Prefect. Then my mates all wanted to go faster, too – purely horsepower in those days, I didn’t touch the chassis. I had a deal with my boss that I could stay behind at nights and use the cylinder boring and balancing machines, camshaft grinder and so on for my own projects and the company ended up with a reputation for doing high-performance engineering work. I used my pals as guinea pigs, but was allowed to give them a discounted rate. Occasionally there were blow-ups, to which my response was usually, ‘Sorry mate, but at least it didn’t cost you much.’ I learned an awful lot, some of it through making mistakes. I also learnt a lot by spending three weeks per year at a technical college near Wellington.

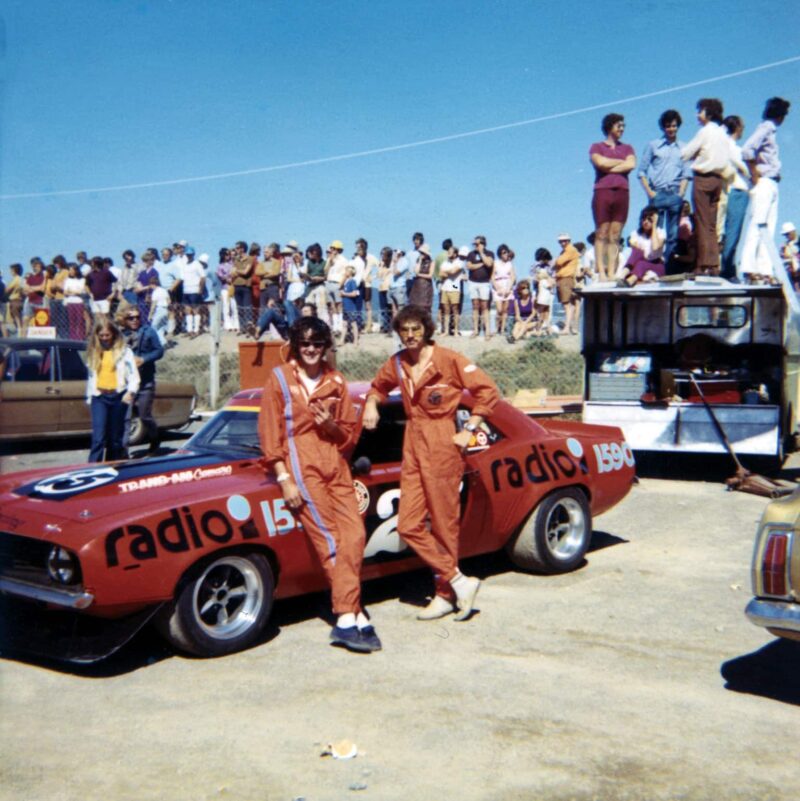

“Through the Otago Sports Car Club I got to know a writer named Alan Dick, who ran a magazine called Auto News. One day it carried an advertisement for a job with Performance Developments, a firm in Auckland, the hub of most professional NZ motor sport. He put in a word for me and after an interview I was hired, which meant leaving behind my friends in Dunedin but I needed to move on. I was there from 1969-1972 and absolutely loved it. I developed V8 engines for speedboats and prepared a racing Camaro for one of my bosses, Dennis Marwood, a quick driver.

“One night, I met this young racer called David Oxton at the Auckland Car Club. He was competing in FF1600 and I helped tune the engine he used to win the New Zealand championship, for which the prize was a trip to the UK to race in the 1972 Formula Ford World Cup at Brands Hatch. He asked whether I wanted to accompany him. I’d only ever left NZ once – and that was to go to a race meeting in Australia! – but I’d read all these books about Cosworth, Alan Mann Racing and so on in the UK, so really fancied the trip. David was planning to stay for about six months, but I thought I might as well hang around for a little while to get some experience. I told my bosses that I’d be back in a couple of years and they were very understanding.”

Bennetts still refers to New Zealand as ‘home’, but he hasn’t been based there since…

“We arrived a few months before the event,” he adds, “because we had to learn about the local racing culture, the treaded tyres – Formula Ford ran on slicks in NZ – and so on. We prepared David’s Merlyn Mk11A in a lock-up garage in Egham, where we tapped into somebody else’s power supply so that we had lights to work at night – typical Kiwi ingenuity, although we were evicted when we got caught.”

After entering several events to prepare for Brands Hatch, Oxton qualified on pole for the big race but crashed at Paddock on lap two while attempting to wrest the lead from rival Johnny Gerber. “We spent the night in a pub, dissecting what had gone wrong,” Bennetts says, “after which David went home while I tried to find a job. I ended up with Racing Services Engines in Strawberry Hill, Twickenham – a workshop right by the Thames. Every time the river level rose we’d be told not to go in because the place would be flooded. I had a great time there, but knew a fair bit about engines by now and wanted to start learning more about chassis. Through a Kiwi connection I landed a post with March’s F2 team in ’75, but stayed only a year because but I felt the company had too many middle managers. It was too political and I just wanted to build and engineer racing cars.

“Fred Opert then offered me a position – and my first job was to go to New Zealand, to run his Chevron BMW F2 car for Brian Redman. I spent two years with the team and we won the NZ Formula Pacific title with Keke Rosberg in both 1977 and 1978, but once Fred learned I could build an engine he’d be asking me to do all sorts of stuff. ‘Can you just pop over to Daytona to work on a Super Vee?’ I told him, ‘I can do a bit here and a bit there, but you’re asking me to do too much.’ It was my task to look after currency exchange in Europe, do the accounts, run cars, rebuild engines… I liked Fred, but needed to find something more stable, to stop living in a suitcase. If nothing else, it was hard trying to keep a girlfriend for any length of time because I was never at home.”

Bennetts in the WSR trophy room with the first car the team ran – Jonathan Palmer’s 1981 British F3 title-winning Ralt RT3

His next move kept him in European F2, initially at least. “I’d met Ron Dennis in the F2 paddock and he offered me a job with his Project 4 team. They were running Eddie Cheever and Ingo Hoffmann in F2. But then P4 was contracted to assemble cars from kits for the new BMW M1 Procar series. There were four of us and we built 24 customer cars, working stupidly long shifts – 14-plus hour days – so we were all absolutely knackered. Ron then asked us to build one more, for the team’s own use, but he wouldn’t tell us who’d be driving. I mentioned that we were all shattered, but he talked us into doing it.

“I asked how we’d transport the car and he told us to use our old F3 truck. I pointed out that it only had a half-ton tail lift and that the Procar was a lot heavier, but he insisted it would be OK. We finished the car at about 3am and had to be at Silverstone that morning, but when we tried to load the truck the tail lift rose about three feet before the hydraulics packed up. I had to phone Ron at 3.40am to tell him what had happened, but he just said, ‘Look, the car has to be at Silverstone by nine…’ So we removed the old hydraulics, fitted new Aeroquip hoses, bled the system, loaded the race car, went home, had a shower, returned to the factory and took it to Silverstone. Shortly after we arrived a helicopter landed and out popped Niki Lauda, the first clue we’d had about our driver. Ron asked whether I was happy now and I replied, ‘Yes, but I’d still like some sleep…’”

Bennetts oversaw Lauda’s run to the 1979 Procar title and ran the car again the following season, this time for Hans Stuck. “The chalk-and-cheese difference was interesting,” he says. “Niki was always serious and professional, Hans always laughing and joking, but each was very quick. We won at Monaco with both drivers, the only difference being that Hans finished the race with all four wheel arches missing…

Mika Häkkinen was one of WSR’s five F3 champions. Below, with Niki Lauda’s successful BMW Procar

“The sponsorship ran out before the 1980 season ended, so I was about to leave and find another position when Ron said, ‘No, I’d like you to go and help John Barnard on our new project’ – which, with Ron about to take over McLaren, became the MP4/1, the first carbon F1 car. I have a reputation for being meticulous, but John was even more so! After a couple of months I wasn’t enjoying it. It was interesting, but it wasn’t an avenue I wanted to pursue. My flat-mates at that time all worked in F1 and kept complaining about the long hours. It wasn’t so much that – I was never afraid of hard work – as the fact that in F1 you became just a number, allocated to very specific tasks, and weren’t properly versatile – and that was almost 40 years ago. Things have become much, much more specialised since.

With Niki Lauda’s successful BMW Procar

“When I told Ron he said, ‘That’s OK, I have something else for you.’ His F3 team was struggling, so he asked me to take the helm. I pointed out that I’d never worked in F3, but he told me I’d soon get the hang of it. We were running Stefan Johansson’s March 803, on which we found the front bulkhead was flexing. I made a sort of light-hearted remark to Ron that the new Ralt RT3 seemed to be going well in the hands of a Kiwi, Rob Wilson, so next thing I know we’re at the Ralt factory and he’d ordered a car. ‘Hang on,’ I said. ‘I didn’t say I wanted one, just that I thought it had potential…’

“We couldn’t get it to lap faster than the March during initial testing. We didn’t have data-logging then, so I took a bit of a punt by nearly doubling the spring rates and straight away I could tell via the stopwatch that it was better. Ron was forever asking when we would race the new car, but now we knew we were on the right lines – and Stefan went on to win the final four races and the title.”

With Dennis winding up his F2 and F3 teams to focus on McLaren, Bennetts had committed to leave but first agreed to sell the Ralt F3 on Dennis’s behalf. Enter Mike Cox from West Surrey Engineering, who had been backing young Formula Ford racer Jonathan Palmer. “Mike was interested in buying the car for Jonathan, so we went to test at Goodwood and JP was properly quick – I was impressed. They subsequently bought it, but JP rang me a couple of weeks later to say they could no longer match the times they’d set originally. I went to have a look and they’d altered the set-up. I pointed out that they couldn’t use what they knew from FF1600, that this was very different, then changed it back for them. We returned to Goodwod and JP lapped faster than Stefan had ever gone. I thought, ‘Bloody hell, this guy’s good – and so is his feedback.’ I told them they needed to get somebody experienced to run it, or they’d have wasted their money. So they asked whether I was free. I agreed – so long as it was done properly. I went back to NZ to run David Oxton in Formula Pacific in a Ralt RT4 and kept in touch with Mike by Telex…

Mika Hakkinen was one of WSR’s five F3 champions

Motorsport Images

“When I returned we had a small workshop in Charlton Village, near Ashford [Middx], and an old A-series Ford transporter that wasn’t big enough to take a complete F3 car, so we had to remove the nose box to transport it. It wasn’t quite what I’d had in mind, but just called ourselves WSE, after Mike’s business, and we did OK.”

In this instance, ‘OK’ translates to winning the opening four races and the championship title. “By the standards of the day we were running on a shoestring and repairing things that we should have been replacing. It was tough, but good fun. The fact I knew the car well from 1980 helped us to get a flying start, but other teams had more money and gradually caught up.”

The team’s hopes were derailed by a late-season exclusion at Silverstone – “We’d been getting aero tips from F1 friends, who were using this plastic stuff to seal airflow around the rear wheels. In trying to make things look nice, we accidentally made the bodywork too wide…” At the time the prescribed penalty for disqualification was loss of points accumulated on the day – six for second place – plus two maximum scores, but the team argued successfully in court that its punishment should be no more than six. Palmer would be champion.

The team became West Surrey Racing in 1982, when Enrique ‘Quique’ Mansilla came on board and finished second to Tommy Byrne in the F3 standings, and at the year’s end Bennetts gave double FF2000 champion Ayrton Senna his F3 debut in a non-championship race at Thruxton. “I wasn’t just struck by his obvious speed,” he says. “He was only 22, but seemed incredibly professional and very commercially aware. He had some funny ideas, though. After we’d done a deal for ’83, he returned to Brazil and was then disappointed when he came back to find we’d bought a new chassis.”

He ran Brian Redman for Fred Opert in 1976

“Where’s my Thruxton car?”

“We’ve sold it.”

“But I wanted to race it.”

“You can’t, it’s gone to someone in Austria.”

“It was a good car.”

“We know, but this one will be even better…”

The proof of that? A run of nine straight victories at the start of the campaign, although an accident at Silverstone in June – during a combined European and British championship event – triggered a period of inconsistency that allowed Martin Brundle to emerge as a serious threat to the Brazilian’s title hopes.

“The second half of the season was hard,” Bennetts says. “Take Cadwell Park… It was 9.25am and Ayrton was already quickest, but felt he could go even faster. We made a quick change to reduce some understeer, but he then ran slightly wide at The Mountain, kept his foot in and speared straight into a concrete marshalling post, flat out. The chassis was totalled and I was back in the King’s Head, Shepperton, just before two in the afternoon. My mates looked and said, ‘We thought you were racing in Lincolnshire.’ I replied, ‘We were…’

“Ayrton and I had a slight difference of opinion at Oulton Park, when I suggested he should settle for second behind Martin if they were running in that order, because he’d been throwing away points and by finishing second he’d drop only three – or two if he could set fastest lap. He said, ‘But I want to win.’ I pointed out that he didn’t have to, that he could finish second to Martin in the remaining races and still take the title, but with him it was always, ‘Why should I finish second?’”

With Jordi Gene and Rubens Barrichello at Fuji in 1991

Running behind Brundle, he crashed again and the title wouldn’t be settled until the Thruxton finale, which Senna dominated. “For all his latent speed,” Bennetts says, “it was the end-of-season Macau GP that marked him out for me as something truly special. It was the first time the race had run to F3 regs, so none of the teams had been before, but the cream of Europe was there. Nobody had so much as seen the track and it was worse for us, because Ayrton had been testing with Brabham at Paul Ricard and didn’t arrive until very late. After he’d been quickest in Friday qualifying, someone allegedly got him on vodka or similar and I’ve been told that one of his drinks was spiked, although I’ve never known the full truth. We didn’t run on Saturday in those days, but we’d arranged a debrief and he turned up a couple of hours late – most unlike him, but he finally appeared saying he felt unwell. Then he blitzed race one on Sunday, despite still being out of sorts, and went off for a sleep before part two. When he reappeared about an hour before the start, I asked what he wanted changing.

“Nothing. Just fuel and tyres, let’s go.”

“You must want something doing.

“No, the car’s fine – there’s still more to come from me. And off he went, to dominate. That really made me think ‘Wow’.”

From 1984, WSR was supposed to become more commercially self-sufficient. There was a deal in place for Roberto Moreno to lead the F3 team, the experienced Brazilian a useful foil for rookie Gary Evans. That deal fell through, however, and Spaniard Juan Carlos Abella stepped in alongside Evans, who notched up the team’s only victory, at Thruxton.

The following year Senna was back on the radar, introducing his good friend Maurício Gugelmin to WSR. “Maurício didn’t quite have Ayrton’s raw talent,” Bennetts says, “but his feedback was unreal. It was the first year of flat-bottom cars after the ground-effect era – and the new Ralt RT30 had a built-in design fault, which we sussed but tried to keep from designer Ron Tauranac. He got to hear and phoned me, asking what we’d found. I told him there had been something amiss with his front geometry, but wouldn’t tell him what! To be fair he found the mistake in the factory drawings, but we asked him not to tell the other teams straight away because it was WSR that had identified the problem. We asked for a grace period of four races and he allowed us two before letting everyone else know.

Gugelmin took the title and followed up with victory in Macau, where Bennetts chipped a bone in his knee when jumping from the pit wall to celebrate his driver taking pole. He had reparative microsurgery just as preparations for the 1986 season were beginning – and new driver Bertrand Fabi, a promising young Canadian, collected him from hospital en route to a test at Goodwood.

Later that day, Fabi was to crash heavily at Madgwick. This was a dozen years before Goodwood reopened for racing and the earth banks around the track were all but frozen. The car struck one of them almost head on and Fabi succumbed to his injuries the following day, “That was a terribly sad time for all of us,” says Bennetts, who admits that recollections from the day upset him still. “He was a genuinely nice guy and had a great future ahead of him.

Bennetts built a 6-litre V8 for the Camaro campaigned in New Zealand by Dennis Marwood, one of his bosses

Bennetts

“We had planned to run Damon Hill alongside Bertrand, but in the wake of the accident I felt like giving up – and in any case Damon didn’t really have enough sponsorship, so I put him in touch with Murray Taylor Racing and told my guys to take a few days off. I really didn’t know what I was going to do, but then Maurício rang, to sympathise about what had happened.

“He also asked whether I would consider running him in F3000. I’d had no previous involvement, but he insisted. Apparently, I’d mucked up his plans because he’d budgeted for two years with me in F3, but we’d spoilt that by winning the title at the first attempt…

“I just didn’t enjoy F3000, though, because I didn’t feel we could give Maurício the best tools for the job in view of our lack of experience. During that summer, Bertrand Gachot asked whether I’d be prepared to run him in F3 with Marlboro money in 1987. It wasn’t a difficult decision to go back to what I knew.”

WSR ran the Marlboro F3 young driver academy for eight years, which put Bennetts in touch with drivers such as Eddie Irvine, Allan McNish, Mika Häkkinen, Jordi Gené, Marc Goossens and Vincent Radermecker – with the independently sponsored Rubens Barrichello thrown in along the way. He and Häkkinen both won the F3 title, while Bennetts considers McNish to have been “the moral champion” in 1989, although a court ruling on rival David Brabham’s engine legality determined otherwise.

West Surrey Racing sorted the new Ralt RT30 more quickly than rivals, and Mauricio Gugelmin took the the British F3 title in 1985

Motorsport Images

“Allan was very good,” Bennetts says. “Mika was a great natural talent – absolutely nothing bothered him – and Rubens was quite remarkable for a 17-year-old, given that drivers tended not to be quite that young back then.”

The Brazilian would be WSR’s last F3 champion, though the team remained a front-runner, and by 1995 Bennetts was casting around for opportunities away from his comfort zone.

“It was simply time for a fresh challenge,” he says. “And besides, by then all the teams were running Dallaras, which were such good cars that some of the engineering ingenuity was no longer there. You could take delivery from Italy and 24 hours later put the car on track and win a race.

“At around the same time fellow Kiwi Paul Radisich invited me to come to Brands Hatch and watch him in action with Ford, in the British Touring Car Championship. He told me I ought to get involved.”

Despite WSR’s exclusively single-seater background, Bennetts was invited to run the official Ford team from 1996, but things didn’t begin smoothly. “You couldn’t really blame anyone,” he says. “Ford had been running with Andy Rouse, but made a very late call to ask Reynard to design and build the cars and get us to run them, but it was so late that Reynard didn’t have time and we ended up going to Schübel Motorsport in Germany, to get a couple of cars that had been racing in four-wheel-drive trim.

They converted them, but the drivetrain wasn’t strong enough to take power only at the front and we had a succession of mechanical failures – halfway through the season I was almost thinking about walking away. This was supposed to be enjoyable…

WSR switched to F3000 for a single season, running Gugelmin in a March 86B. It proved a frustrating 1986

Motorsport Images

“For 1997 we had a Reynard-built car, but it was the company’s first BTCC project and some of the knowledge it had from single-seater racing – carbon-fibre engine mounts, a lot of high-tech stuff – didn’t really translate to a steel-shelled road car. The problems continued, but we managed to dial many of them out and by 1998 we’d started to get a bit of development going. We finally secured our first win, with Will Hoy at Silverstone, but that owed less to an improved chassis than it did to our pit equipment. We’d invested in some trick multi-pointed sockets from America and, when it rained, we were able to change all four wheels about 10sec quicker than anyone else…

Bennetts planned to stay for just a couple of years when he first came to England. That was 1972…

“We had a verbal agreement with Ford to start building the cars ourselves for ’99, but it was kept quiet until Reynard had officially been told. In the meantime, somebody else at Ford had approached Prodrive about doing the job. It was a bit of a shock to several people when they found out we’d already started building shells, but it was eventually settled out of court and our old friend Ron Tauranac, who had strong ties with Honda from his Brabham days, put in a good word for us about taking over the company’s BTCC programme, which had been run by Prodrive!”

With Allan McNish and Marlboro coach James Hunt. McNish was the ‘moral champion” in 1989 according to Bennetts after the Scot lost the title on a technicality

Motorsport Images

WSR won first time out with Honda, courtesy of James Thompson, and also took the final two races of the UK’s Super Touring era, with Tom Kristensen at Silverstone in 2000. It ran the MG ZS project from 2001, won its first BTCC title in 2004 – when Anthony Reid emerged as champion Independent – and really began to hit its stride after beginning an association with BMW in 2007. He has been in and out of the team a couple of times due to the vagaries of sponsorship, but Colin Turkington has been pivotal to the team’s tin-top success – three times an outright champion, most recently in 2018, and four times the winning Independent.

“We first ran Colin back in 2002,” Bennetts says, “and he’s impressive – intelligent, focused, determined. He keeps an incredible amount of information from every track session. When we’re having a debrief, he sometimes gets out this big file and says, ‘Are you sure?’ Sometimes he’ll question what we’re doing, because he thinks we’ve tried it before to no real avail, and when we check he’s usually right. His memory retention is incredible.

“A lot of drivers can go quickly but can’t explain how they’ve done it in any kind of detail. Drivers often just want to look at the data, but I try to stop that. We didn’t have telemetry when I started running a team; everything was relayed through the seat of your pants, and I encourage them to learn that, so that they are better able to tell us what the car is doing and help them further their career.”

Does he enjoy touring car racing as much as he did single-seaters? “Winning is winning, whether it’s F3 or the BTCC,” he says, “but I guess there’s an extra buzz when you do it with your own designed and developed car. There are some common parts in the BTCC, but we still feel the BMW 1-series is ours, whereas in F3 you were winning with a customer chassis.

“Plus, the BTCC is a good place to be. If you’re looking to run a professional business, I reckon you need to budget about £550,000-600,000 per car per season, although you can obviously do it more cheaply. To put that in context, during the latter Super Touring era the likes of Nissan and Ford were reputedly spending almost £10 million annually on a national championship programme. Now, for a fraction of that price you have 30 races, live terrestrial TV, exciting racing… It’s a good championship, a good show.”

And are there any regrets that he’s never worked in F1? Bennetts smiles. “Absolutely none. Ron Dennis has sometimes gently teased me about how much more I could have made if I’d stayed with him, but money has never been everything to me. I just like motor sport.”