Lunch with... AJ Foyt

Having honed his craft in the toughest of racing schools, he conquered Indy, Le Mans, NASCAR... and pretty much everything else he tried

Julie Soefer

Flying in from London I had to clear US immigration at Newark, New Jersey, which is not one of the world’s loveliest airports. At last I got to the end of the disgruntled queue to have my passport and fingerprints checked. The paunchy border official, slumped behind his desk, was ungracious and unsmiling, barely lifting his hooded eyelids to look at me as he grunted through his routine: “Where from? Destination? Reason for visit?” In reply to the third I said, “I’m a journalist” and, because this often produces an unwelcome reaction, I added diffidently, “I’m flying on to Texas to interview AJ Foyt.”

The effect on the official was instantaneous and galvanising. He sat up straight, opened his eyes fully, and beamed at me. “Hey, you goin’ to see ol’ AJ? He still kickin’ ass?”

Yes, I replied, ol’ AJ is still kickin’ ass.

At that moment I was reminded, not that I needed any reminding, that Foyt remains today what he has been for half a century: a true coast-to-coast, blue-collar, all-American hero. Not many hours later I am driving west out of Houston, across Texas plains that stretch from horizon to horizon, until I find a road arrowing off left that is called, in his honour, AJ Foyt Parkway. Some miles further on a large spread of anonymous low buildings tells me I have arrived at AJ Foyt Racing. I am met by the gentle and charming Anne Fornoro, who has been AJ’s PA and publicist for nearly 30 years, and is herself the daughter of Russ Klar, a noted 1950s sprint car and Indy racer. Her brother Greg is currently working on the Foyt premises, restoring their father’s 1940s Midget racer.

At the front of the main building a packed museum contains generations of racing cars, trophies, flags, helmets and posters from AJ’s long career. At the back are the spacious, surgery-clean workshops where the current cars are prepared, for AJ Foyt Racing is very much a hard-edged Indycar team, with AJ’s son Larry in the role of Team Director. In 2015 they are running Takuma Sato and promising Brit Jack Hawksworth, using Honda engines, and during the season they’ll be based at their own dedicated facility in Speedway, Indiana.

Foyt in 1961, the year of his first Indy 500 victory

IMS

Between museum and workshops are the offices. In the biggest of these, sitting at a big desk and surrounded by yet more memorabilia from a lifetime’s racing, is the big man. His reputation has always preceded him as someone who doesn’t like to have his time wasted and can display a short fuse. But as he shakes my hand in an iron grip, his greeting is welcoming and genuinely friendly. He is 80 years old this January 16, and carries more weight than at the start of his long career. But the determined jaw and piercing eyes are exactly as they have always been.

The first task is to settle where we should eat. I always ask my Lunch With…. guests to choose their favourite restaurant. Says AJ: “Nothin’ around here but The Back Door. A burger there do ya?” To lunch with AJ, I’d eat grass. I say that a hamburger is fine, and mention – unwisely – that when I went to Nazareth for Lunch With Mario Andretti, we had a hamburger. For a moment the eyes harden and the jaw juts a little further. Clearly he doesn’t like to be compared with SuperWop, and I have briefly forgotten that, somewhere along the line, Foyt and Andretti had issues.

We set off along the dusty road, AJ driving his favourite truck with Anne, who’s also coming to lunch, while the photographer and I follow in our car. The Back Door turns out to be a wooden shack standing lonely by the roadside, with a friendly proprietor, a list of various burgers listed above the counter, and a couple of road-menders the only other occupants, sitting in their overalls at one of the few small tables. With the confidence of long familiarity AJ chooses our burgers, and when they come mine is very large, and very good. Politely I comment to AJ on its excellence and, very briefly, the eyes go hard again: “Better than Andretti’s burger, huh?” Yes, AJ, definitely.

Anthony Joseph Foyt II was born in Houston 80 years ago, and grew up in a tough area called The Heights – “so tough people locked their car doors when they drove through it. Right from a kid you learned to take care of yourself, or someone’d beat the shit out of you.” His father Tony had a garage with an old Air Force friend, Dale Burt, and both of them raced on the local dirt tracks on Friday and Saturday nights. As soon as he could walk AJ became a keen member of the team, and when he was five his father made him a little lawnmower-powered racer with which he wore a groove in the yard.

When he was 11, one evening when his parents were out, AJ got his daddy’s Ford V8-powered Midget racer off its trailer. He climbed aboard and was roaring around the back of the Foyts’ little two-room bungalow when a blow-back through the carburettor set the car on fire. He tore off his shirt and smothered the fire with little more than blackened paint for the car, but badly burned hands for AJ. “But I reckoned my ass was goin’ to hurt worse when my daddy got home.” He got the racer put away, and when his parents returned he was in bed with his eyes tight shut. His father wasn’t convinced, but maybe he’d resigned himself to his boy being a race car driver, because nothing more was said.

AJ was driving his friends’ cars before he was legally old enough, and as soon as the licence came he bought an ancient Oldsmobile, and hopped it up within an inch of its life. Having worked on Tony’s and Dale’s cars, he was already a very good mechanic. He challenged his pals on the local roads, and they also broke into the local Arrowhead track at night and raced there under cover of darkness. Stories began to filter back to Tony, and he told AJ he had to stop racing on the street “or he’d whup my butt.

“I decided logarithms and Wordsworth weren’t going to help my racing career, so I quit school, found a 1939 Ford coupe for 100 bucks and built it up into a stock car. My first race was on dirt at Playland Park.” He learned fast, and the wins started to come. Next he talked his way into a borrowed Midget, an old and uncompetitive car, and put on such a hairy sideways show keeping up with the newer machinery that his dad and a friend scraped together $800 for a decent Kurtis Midget chassis. Its four-cylinder Offy engine came from the wreck of a friend’s fatal crash. “Those little engines had about 100 horsepower, so they went pretty good.”

And AJ went pretty good, too. In his first outing he won everything: the initial Trophy Dash, then his heat, then the semi. In the final he fought past local hero Tommy Rackley to win that too – although it was an elbow-to-elbow battle, and Rackley wanted a fist fight in the paddock afterwards.

Celebrating a fourth Indy 500 success in 1977

IMS

In those days jeans and an oily T-shirt were a driver’s normal race wear, but now AJ was racing in red silk shirt and immaculate white pants. “I wanted the car and me to look smart. I had no money, the few dollars I won I put back in the car. I kept just back enough to eat. I’d sleep in the towcar or, if the weather was dry, on the ground. I was the cheapest racer around.” All over Texas, into Louisiana and Oklahoma, the teenage Foyt became the man to beat. It was a school of hard knocks: after one race a guy punched him while he was still in the car. “I couldn’t get to him, so Daddy beat the hell out of him.” There was cheating, too. “Guys would punch out their engines [increase their capacity] but every time my engine was protested I’d say, Go ahead, pull it down, I don’t care. They always found it was legal.”

In 1955, now 20, AJ used his prowess in Midgets to wangle rides in the bigger Sprint cars, and started to go further afield. St Paul, Minnesota, 1200 miles from Houston towards the Canadian border, was called the Indianapolis of Sprint car racing. Against a 60-strong entry, AJ qualified on pole and won the race. There was a fight after that one, too, but even though AJ was outnumbered by the locals he gave as good as he got.

“As well as Sprint cars I was still driving Midgets, Stock Cars, anything I could get into. Wally Meskowski gave me some Sprint car rides, and that got me noticed some more, and in 1958 I got my first ride in the Indianapolis 500, in the Dean Van Lines Special run by Clint Brawner. Because I was the new guy Pat O’Connor, who’d had the pole the year before, offered to lead me around for a few laps. He was really good to me. I had to do my rookie test: 10 laps each at average speeds of 120, 125, 130 and 135. It had to be just right, one mistake and you were out. Did that, and then I started to work away to find my groove. At Indy all four corners are completely different, you have to learn the characteristics of each. And how the wind was blowing was much more of a factor than later, when ground-effects came in. The track felt big and the car felt big.” The youngest driver there, AJ averaged over 143mph to qualify 12th fastest.

The race started in the worst possible way. “The drivers tell you, watch for the draft, watch for this, watch for that, then everybody’s crashing, what the hell do you watch for now?” On the first lap front row men Dick Rathmann and Ed Elisian touched, and started a 15-car accident that ricocheted down the field. AJ’s new friend Pat O’Connor, from the middle of row two, was caught up in it, and his car cartwheeled into the air, landed upside down and burst into flames. O’Connor was incinerated inside. Foyt, from row four, spun to avoid the carnage, and managed to drive on. “I come round next lap and Pat’s burning there. I say to myself, AJ, is this tough or not? I raced on, and after 400 miles I had a water hose break in Turn One, spun on my own water but missed the wall. That was me done, but they gave me 16th place. That was my first Indy.”

What almost defies belief is that AJ was still racing at Indy 34 years later. In those three and a half decades racing car design changed out of all recognition. He started as a young charger in the big solid-axle front-engined Offy roadsters, and he was still a charger in the rear-engined monocoques with multi-cylinder, multi-cam turbocharged engines and ground-effect aerodynamics. His wins spanned the generations: he was a great racer in the Fifties and a great racer in the Nineties.

For Indy in 1959 rollover bars and fire suits became mandatory, but Jerry Unser and Bob Cortner both died in practice. AJ qualified 16th after blowing an engine, got up to fifth, then more problems dropped him to 10th.

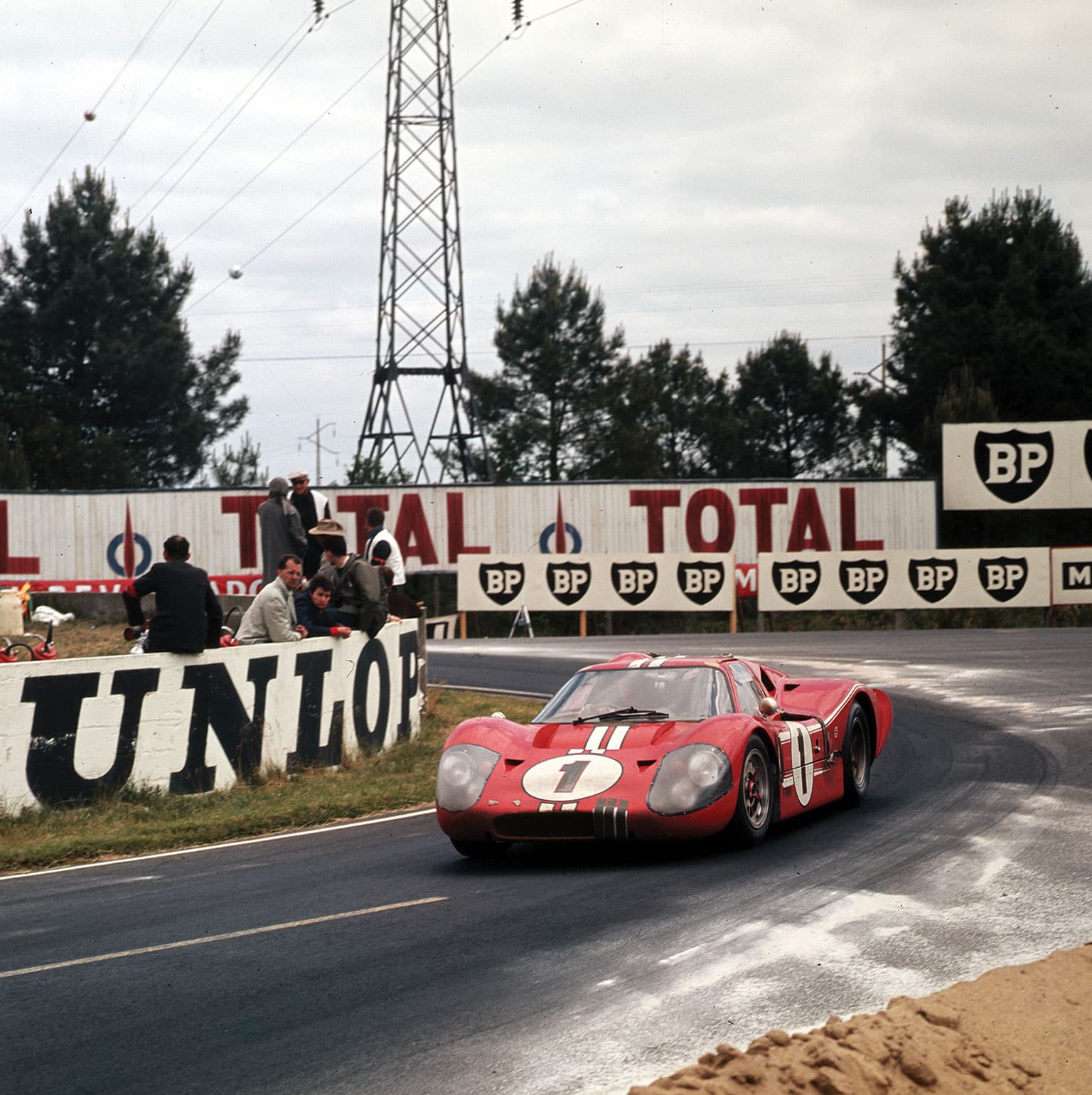

Le Mans success with Dan Gurney in 1967

Motorsport Images

That year he travelled out of the US for the first time, to Italy for the Race of the Two Worlds. “The high Monza banking was unbelievable. We were doing 175 around there.” AJ took over the Kuzma-Offy that Maurice Trintignant had started and finished sixth, despite breaking his crank before the end.

Double USAC champion Jimmy Bryan, who’d won AJ’s first Indy in 1958 and also the first Monza Two Worlds race, finished second that day. “Jimmy always raced with a cigar butt in his mouth. In 1960 he retired after a 10-year career, but the Langhorne promoter paid him a lot of dollars to come back and do one last race. Jim Hurtubise was on pole, Jimmy qualified second with me third. From the start we went into Turn One, Bryan went end over end and was killed. I won the race.”

By 1960, his second full year in the top USAC category, AJ had started a successful but often stormy working relationship with legendary engineer George Bignotti. At Indy a blown clutch ended his race, but thereafter things came right. AJ won four of the last six races of the season, and took the title from under Rodger Ward’s nose. At 25, he was USAC champion. He would be champion again three times in the next four years, and seven times in all.

The longed-for Indianapolis 500 victory came in 1961 – and there was a surprise in the paddock. AJ said later: “We all think green is a bad colour. You don’t wear green socks, or drive a green hire car. And this guy turns up with a green race car. If that wasn’t enough, the son of a bitch had its engine in the back.” Another Indy wag described the visitors as “Guys with college degrees who didn’t know their ass from their elbow.” But Jack Brabham’s Cooper-Climax started 13th and finished ninth, and quietly sowed the seeds of a revolution.

Indy started badly that year when 1958 USAC champion Tony Bettenhausen offered to try Paul Russo’s car in practice to help sort its tricky handling. “He told them to put more castor on. They took a bolt out to adjust it and didn’t put it back in tight. Going down into Turn One the suspension came apart.” In the ensuing fatal accident the car wrapped itself up in a length of steel wire fencing. AJ counted Bettenhausen as another friend, and when he heard the news he threw his helmet across his garage in fury. Then he picked it up and got back in his car.

In the race he came up from ninth on the grid to fight an enthralling battle with poleman Eddie Sachs, an Indy veteran whose motto was, “If you can’t win, be spectacular.” One of AJ’s refuelling stops went wrong and he had to make an extra stop, but he won by 8.3sec, netting the Bignotti team $118,000 – a huge sum half a century ago. AJ’s share was 40 per cent. Afterwards he went back to work in his father’s little garage as usual. “A lady came in, said to my daddy, ‘Now your boy has won the big race, I guess we won’t be seeing him in here no more.’ He said, ‘He’s under the dash of that car over there, changing a speedo cable. He’s the same today as he was last week’.”

AJ’s second Indy win came in 1964, the last for a front-engined car. “These strange rear-engined things had started to appear. Colin Chapman had an inside line to Ford, so his Lotuses got their new four-cam V8 engine.” The fastest of the visiting Europeans, one Jim Clark, took a sensational pole, and led until chunking tyres broke his suspension. On the second lap Dave MacDonald lost control of his unconventional Mickey Thompson car, which hit the wall and exploded into flames. Eddie Sachs hit the burning wreck in front of him, and his car went on fire too.

In action at Le Mans in 1967 with the Ford GT

Motorsport Images

By tradition the Indianapolis winner, as soon as he got the laurel wreath around his neck, had a bottle of milk thrust into his hands to drink for the cameras, plus a newspaper hot from the presses with his own name in the headline. In 1964 the headline said: Foyt winner in 500: Sachs, MacDonald die.

The victory pictures show Foyt stern-faced. “It was a win, but not a win I liked. I didn’t have to learn it from the newspaper, I already knew they were dead. There was too much fire out there.”

By the end of 1964 AJ had already scored the most USAC championship wins in history, at 28. But he was still racing in Sprint cars and even Midgets when he could fit them in – and an incident in a Sprint car race at Terre Haute briefly got him banned. “I was going around Johnny White and he put me in the fence. I told him: Quit flying up inside me to get me into trouble. Next race, at Williams Grove, I’m on the outside and he swerves in front of me, I get into the wall a little bit, so I wind up second. Afterwards I went over, he gave me some sauce, so I hit him.” But AJ’s licence was returned after fellow racer Roger McCluskey said in his evidence that AJ had manhandled White but hadn’t actually hit him. “If he had,” said McCluskey, “he’d have tore his head off.”

AJ and White had made up their differences by the next race, at Terre Haute again, when AJ broke the track record in qualifying. “Johnny went out after me, wanted to beat my time, and flipped over the wall. He was paralysed from the neck down after that. They used to wheel him around to my pit so I could say ‘Hi’.” White died a few years later from his injuries.

Foyt didn’t want to be thought of as just a USAC driver, and would always drive anything that was on offer. His first NASCAR victory came just five weeks after his 1964 Indy win, in the Firecracker 400 at Daytona in a Ray Nichels-prepared Dodge. He won the same race in 1965. “My daddy never liked me running NASCAR. He used to say, ‘You runnin’ those damn taxi cabs again?’ But you got some pretty tough guys in that lot, and I enjoyed going into their back yard and trying to beat them.

“I had my troubles with NASCAR too. At Talladega in 1988 I was running good, and one of the NASCAR boys [Alan Kulwicki] hit me under a yellow. I thought, You son of a bitch. I went after him and spun him round. So they black-flagged me. I come through the pits at about a hundred miles an hour, the guy was holding up a board for me to stop, I wasn’t going to stop, and he had to jump over the wall.” NASCAR imposed a six-month ban and a $20,000 fine, reduced on appeal to a two-month ban – and a $35,000 fine.

One of the biggest accidents in AJ’s career happened in 1965 in a NASCAR race. “I was in a Holman Moody Ford on the Riverside road course, chasing Dan Gurney, Junior Johnson and Marvin Panch. At the end of the long back straight I stand on those big old drum brakes to slow that big old car, and the brakes just fell apart. To avoid hitting the others I had to dive off the track over this steep drop, and the sumbitch took off and went end over end. Next thing, I was waking up in hospital with a broken back, a punctured lung, a smashed heel and several other bones broke. It was the first time I’d really hurt myself in a racing car. The newspapers quoted one of the doctors saying I’d never race again. I said to the doctors, ‘That’s a bunch of bull crap’.”

Eleven weeks after the Riverside accident AJ, still in considerable pain, turned up at the Phoenix USAC race, qualified on pole, and ran near the front until an oil leak stopped him. One week later he did the 500-mile NASCAR race on the oval at Atlanta. His throttle jammed open, he hit the wall hard, and he needed a check-up at the circuit hospital. As he walked back to the pits, race leader Marvin Panch came in and collapsed from heat exhaustion. The Wood Brothers grabbed Foyt, put him in the car, and he drove it to the finish to share the win. It was classic Foyt.

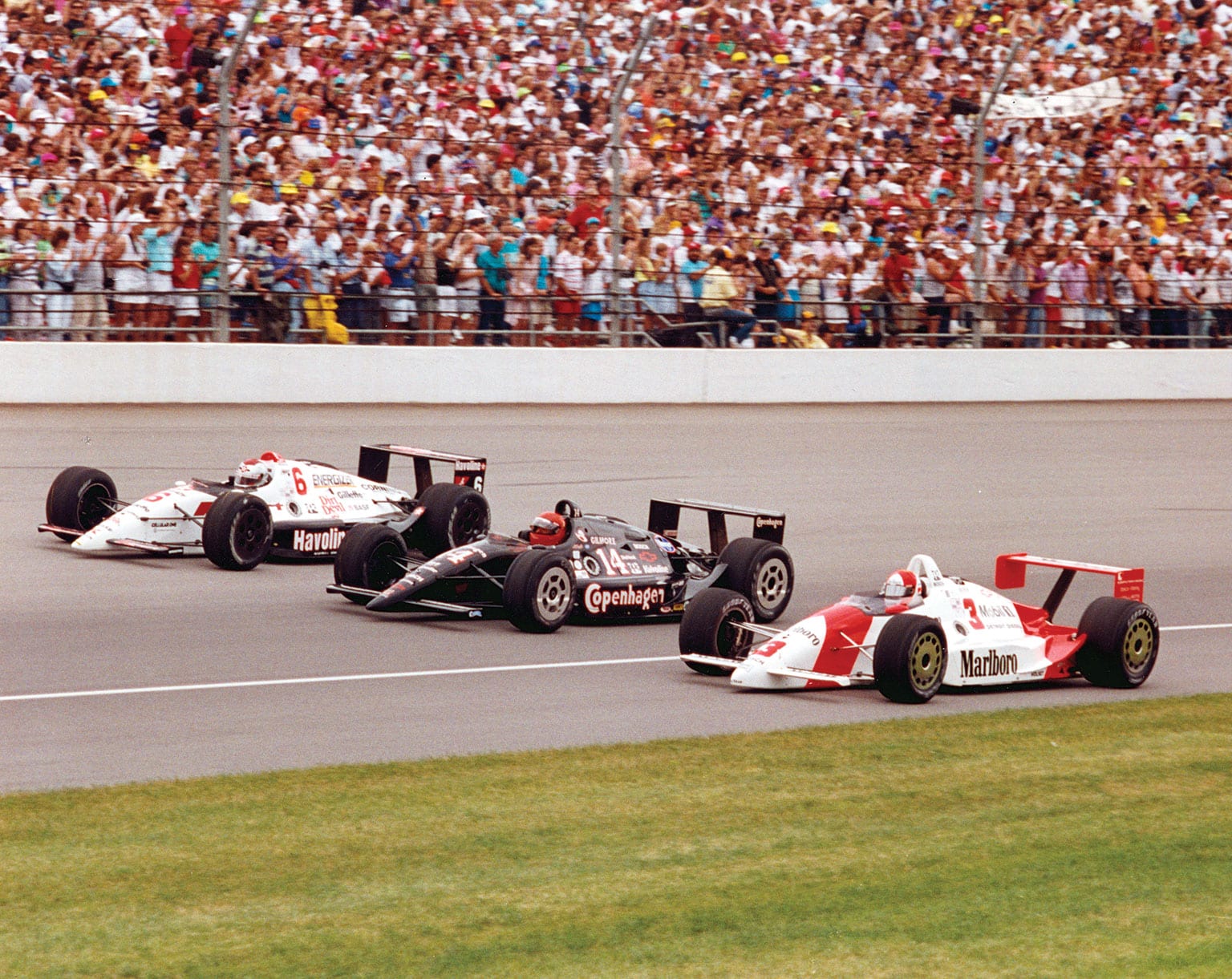

Preparing for the start at Indy in 1991, with Foyt lining up second between Rick Mears and Mario Andretti

IMS

In 1972, driving for the Wood Brothers again, he won NASCAR’s most prestigious race, the Daytona 500. He also won the IROC Series two years running, in 1976 and 1977, in a Chevrolet Camaro. There were Yurrup-style sporty cars too. In 1967 he was recruited as part of Ford’s steamroller effort to vanquish Ferrari in endurance racing. In the Daytona 24 Hours, sharing his 7-litre Mk 2 with Dan Gurney, he was hobbled by various problems, but at Sebring he and Lloyd Ruby were placed second despite a broken camshaft half an hour from the end.

That June he flew to France for his first Le Mans 24 Hours, sharing one of the phalanx of Ford Mk4s and Ford Mk2s with Gurney once again. “Dan and I were good friends, but Le Mans was a new type of race for me. Driving through the night, at about 2am my shift ended, and I came in to hand over to Dan. They said, ‘AJ, we can’t find Dan! You’ve got to stay in.’ So I had to go back out again, driving into the dawn, when it’s really dangerous because the fog moves in and you can’t see. Man, I was tired: Dan was taller than me, his arms were that long, I had to drive stretched out to fit his cockpit position and my arms were killing me. Dan told me later he was asleep, but I told him, ‘Damn you, Gurney, you did it on purpose.’

“At about 4am Andretti crashed his Ford, just about cut the car in half, and they took him off to hospital. We drove on, 3250 miles, and we won the thing. Fastest Le Mans ever up to then: we averaged over 135mph, day and night. I haven’t been back. I went there as a rookie, I won, what else have I got to prove?” Winning the Indianapolis 500 and the Le Mans 24 Hours 12 days apart, two of the world’s greatest motor races in entirely different disciplines, proved a whole lot.

“I did some more of those endurance races. I won the Daytona 24 Hours in 1983 in a Porsche 935, and I won the Sebring 12 Hours in 1985 in a Porsche 962. I came to Brands Hatch in the 1960s with a sports car, a Scarab. Far as I remember, I stuck it in the wall. And in 1978 we had two Indycar races at Silverstone and Brands a week apart.”

This was a brave promotion by Grovewood boss John Webb, giving British crowds the chance to see how blindingly fast the Indycars were: at Silverstone pole position was 2.5sec under James Hunt’s F1 lap record. AJ forged through the field and towed up on leader Rick Mears on the 190mph run down Hangar Straight into Stowe. “Because of rain in practice, I hadn’t really learned the place. But Jackie Stewart had told me I could go into that corner very tight, it was faster than it looked. I went in there getting on Mears, and I said to myself, Jackie, I hope you ain’t lyin’ to me, if you are I’m gonna end up in that grandstand. I came out of the corner ahead of Rick and I won the race. At Brands I think I got fourth.”

In the 1967 Indy 500 Parnelli Jones in the STP turbine car dominated until a $6 bearing failed with four laps to go, handing the lead to Foyt. “I was a lap ahead, and on the last lap going down the back chute something told me: Just be careful. When I come off Turn Four cars were spinning everywhere, I didn’t know who I was going to hit. I took second gear and somehow got through them to the flag. If I hadn’t slowed down I’d have been right in the middle of it.” His fourth Indy 500 win came 10 years later, in 1977.

Whatever tyre deal AJ had, he would always run on the most competitive equipment. In 1964 he was on a Goodyear contract and tested for months, developing a tyre that would run 500 race miles without a change. “Then they swapped technicians and the tyre they came up with for Indy was shit. Well, winning a race is more important to me than losing a race and moaning to everybody it was the tyres’ fault. So I put on Firestones, and I won the race. Goodyear were pissed, but I sent back Firestone’s bonus cheque.

“In 1974 I was sitting on the Indy pole, and the same weekend there was the Hoosier Hundred, the Friday night race at the Indiana State Fairgrounds, under lights. I hadn’t run my Sprint car on dirt for about five years, I had George Schneider driving it for me. Then he got a chance to drive another car that was winning all the races, and he told me he wanted to switch. I said. ‘George, my car’ll run the hell out of that one.’ He said, ‘Your car can’t beat it.’ I said, ‘Fine, off you go. I’ll drive it.’ Then Parnelli and me, we had a wager. He said, ‘Bet you can’t outrun those top guys who run dirt every week.’ I qualified about ninth, I wasn’t getting the traction I needed, so for the race I put Firestones on the back, kept Goodyears on the front. Well, I won both 50-mile parts, and Leo Mehl, the Goodyear competitions boss, got really mad. He said, ‘AJ, you are embarrassing us’. I said to him, ‘Listen, the Goodyears came home first, the Firestones chased them all night’.”

There are far too many other exploits to list, but I’ll mention AJ’s closed-circuit record. On the Firestone test track at Fort Stockton in 1987 he drove an Oldsmobile Aerotech, a March Indycar chassis with a 2-litre turbo Olds engine and all-enclosed body, at a lap speed of 257.123mph. And there were more crashes, more broken limbs, although: “Not bragging, but I can say all my bad accidents were not because I made a mistake, they were because something broke.” One of the worst came in the CART race at Road America in 1990.

“I blew an engine in qualifying, had to start from the back. I was coming through, and as I was going under someone I hit the brakes real hard and the pedal broke away under my foot. I took off over the bank, and I thought to myself, Sheeyit, this is going to be bad. And it was bad. Took them 45 minutes to cut me out. Both my legs were broke, my feet were back in my face, my toes were all crushed, everything was screwed up. But I never lost consciousness. I said to Terry Trammell, the race doctor, ‘Have you got a big hammer? Hit me over the head, put me out of my misery’.

“They stopped the race, a helicopter came from Milwaukee and landed on the track. I needed lots of blood to keep me alive [one of the donors was his faithful PA, Anne Fornoro].They talked about amputating one of the smashed legs, but eight months later I was back at Indy. They were expecting me to be in a wheelchair, or at least on crutches, but I managed to walk to my car, managed to get myself in, and I qualified on the front row.

“One thing I am proud of, I never missed an Indy 500, 35 years from 1958 until 1992. And I was there in 1993. I knew I could have a good shot at pole, and I was running over 220mph in practice. [He was now 58 years old.] Then the yellow came on. It was Robbie Gordon in my other car and he’d hit the wall. It was about the third time he’d wrecked. There and then I decided, I can’t have a team and race as well. I came into the pits and got out. Everyone said, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘I’m through. It’s over, that’s it’.

“Ever since I left Bignotti in 1966 I’d pretty much had my own team. I’ve now been working just as a team owner for more than 20 years, and I’ve run a NASCAR campaign as well for much of that time. You watch the mistakes your drivers make and you tell them, anything you say, you’re not going to impress me. I don’t care if you hit the wall soft or you hit the wall hard. I’ve done it both ways.

“Of all the drivers who have raced for me, Kenny Bräck was the most professional, he knew what he wanted. He won Indy for me, and the championship. Scott Sharp was good, he won me the championship too. Darren Manning was fast but he wasn’t strong, with all the downforce now you need to stay in shape. Martin Plowman is a super nice kid, can’t really judge him yet, but when he has run for us he has run good. Of our two guys this year Sato is a little guy, he has to work hard to be strong, but he’s fast. Hawksworth, he’s only 22 years old, I think you’ll hear a lot more of him.

“As for the Foyt family, well: Tony, one of my sons, he wasn’t into racing, he’s always loved animals. My other son, Larry, he did NASCAR and Indycar, but he broke his back in the 2005 Indy 500. Now he runs the team with me. My grandson, AJ Foyt IV, we ran him in Indy Lights and he won the series, and in 2003 he became the youngest-ever Indianapolis 500 starter, on his 19th birthday. But he got to thinking he knew more than everybody else, and during Indy qualifying in 2010 I got mad at him and I fired him. He ain’t drivin’ for nobody no more. Now we’ve got my great-grandson, Anthony Joseph the Fifth, he’s four years old. He comes to the shop, walks around the cars, points at one of them and says, ‘That’s me’. Give him 12 years and I tell ya, he’ll be out there.”

Somehow AJ has found time to breed racehorses in Kentucky, invest in the Houston Astros baseball team, and become the biggest Chevrolet dealer in Texas. “I’m not a banquet kind of guy, I don’t like hanging around in bars. I get more of a kick out of baling hay or building a fence.” Behind the scenes he has quietly been very generous to people working for him, and to various charities, but he doesn’t want to talk about any of that. Anne Fornoro has said, “The public sees AJ as mesquite-tough, with a nitro temper apt to flare in a New York minute. What they don’t see is his heart. It’s as big as his home state of Texas.”

As a team owner, AJ is well aware of how the sport has changed. “What I liked about my day as a driver was, when you were out there you didn’t have a computer telling you what you were doing wrong. You and your chief mechanic worked together, and if you weren’t fast enough you figured out what to do. A lot of drivers today, if they didn’t have the computer they wouldn’t know what to do next. You got a driver out there, but at the same time you got a computer.

“About the only thing I see that’s better about racing today is the safety. It’s 100 per cent safer now than how it was then, and I’m real happy about that – although I have to say the accidents they have today, they mostly walk away, so they don’t learn anything.

“Back then a lot of my friends died. You had to be brave or you weren’t fast, but you didn’t win races by being stupid. If you ran out of brains you got killed. Or you lay looking at a hospital wall for a long time and you thought about it, and you decided to try not to make the same mistake twice. I’ve got false knees, false hips, burns, scars all over my body. I guess I paid the price, the price for always wanting to win.”

The burgers are long finished, and AJ wants to get back to running his race team. Once more that iron handshake, back into the truck with Anne, and he’s gone. I’m left totting up the statistics which, if you like such things, are extraordinary. Historians disagree about how many career wins AJ had in different disciplines, but it’s probably more than 250. No one else has won seven USAC titles. No one else has won the biggest races in Indycar, and in NASCAR, and in endurance racing. No one else has been part of the American racing scene, as driver and team owner, for more than 60 years.

But set aside the statistics. For me, more extraordinary is the man. There has never been a motor racing hero quite like AJ Foyt. And surely there never will be again.

AJ Foyt

Career in brief

Born: 16/01/1935, Houston, USA

1953 Began career in Midgets

1958 First of 35 consecutive Indy 500 starts

1960 Won USAC Sprint & National titles

1961 Scored first of four Indy 500 victories

1964 First NASCAR win

1967 Triumphant Le Mans 24 Hours debut

1972 Daytona 500 winner

1983 & 1985 Won Daytona 24 Hours

1993 Retired from the cockpit – during Indy 500 qualifying – to focus on running his racing team