Lunch with... Oliver Gavin

He accepted that he wouldn't make it to F1 early on, but since then he's claimed five ALMS titles and four class victories at Le Mans

James Mitchell

Formula 1 is naturally the summit of every young driver’s ambition, the goal that spurs him on to scale each successive rung of the ladder. When his early efforts go well, when the pundits’ plaudits start to include prognostications of future greatness, the goal creeps closer. But, unless he’s a once-in-a-generation superstar, there will inevitably be a degree of lottery involved. Of a pair of drivers with apparently equal ability, one might make it to F1, one might not; and the deciding factor is not necessarily pure talent, but the way the cards happen to fall. Look through the race reports in the weeklies of 10 or 20 years ago: the odd name stands out that subsequently became a household word, but there are so many others then making headlines who are now totally forgotten. They have become ordinary blokes: businessmen, farmers, garage owners, property developers. Or, in a few cases, they have gone on to make an honest living in other areas of motor sport, continuing to display the ability that merited an F1 drive but did not achieve it.

Oliver Gavin is one such. In his first full season he won 11 out of 12 races, starting every one from pole. Barely 12 months after his first-ever car race, he scooped the prestigious McLaren/Autosport young driver award. He went on to be British F3 Champion, following in the wheel-tracks of Emerson Fittipaldi, Nelson Piquet, Ayrt on Senna and Mika Hakkinen. Then came a couple of unfortunate F3000 deals that turned out to have far less substance than promised, and suddenly Olly’s career was going in the wrong direction. After a summons to compete in the Australian Grand Prix turned sour, Olly had to accept that he would never find himself on an F1 grid.

So he shifted his sights to a works drive in endurance racing. For 11 seasons now he has been a key member of Corvette Racing, and has been rewarded with 41 wins, five Drivers’ Champion titles in the American Le Mans Series, and four class victories at Le Mans. Talking to him, I realise that the levels of fitness, dedication and intelligent professionalism he brings to bear on his race programme are in their way every bit as stringent as an F1 driver’s.

2012 Le Mans was blighted by technical issues

Motorsport Images

Oliver is 40 now, and lives with his wife Helen and three young children in an idyllic country village, off the beaten track but within easy reach of Silverstone. His children go to the local school, where Helen is the chairperson and fundraiser, and social life gathers around a delightful village pub, the Rose & Crown. Not that Olly sees inside it that much: during 2012 he made no fewer than 18 return trips across the Atlantic. When we meet he has just jetted in from the 1000-mile Petit Le Mans race at Road Atlanta. It’s at the Rose & Crown that we take an utterly British lunch: Arbroath smokie topped with fried egg, chicken stuffed with Lincolnshire sausage, and bread and butter pudding with custard. Olly looks as if he can take it: tall, slender and evidently very fit, he has already run five miles that morning.

“I genuinely enjoy running, and I try to do 40 or 50 miles in every week. The cars I race get very hot inside, and you need to retain your ability to concentrate and focus for a long time. Better fitness means you can drive faster for longer, and in testing you can keep working with the team and not get a drop-off in performance. Often with testing, practice, qualifying and then the race, an event will last a full week, which puts a lot of stress on your upper body and your neck, so you need to do plenty of core fitness and circuit training too.

“Endurance used to be just about driving at eight-tenths and keeping the car going. Now each stint is like a Grand Prix, over and over again. We’ll do just under an hour between refuelling stops — at Le Mans the tank is limited to 90 litres — and we stay on the same tyres for two stints. So each driver will double-stint each time, and sometimes we may triple-stint, which means you’re in the car for up to 2hr 45min. That’s why for the long races you need three drivers. Like any professional athlete, you have a medical team behind you: not just to make sure you’re getting the right fluids and reloading carbohydrates, proteins and minerals, but also to understand how you operate mentally. For years, whenever I got out of the car at Le Mans, day or night, I was so amped up I couldn’t leave the garage. The crew chief, the engineers, the mechanics, the other drivers, they were doing their jobs, and there was nothing I could do to influence that. But I was using up a lot of mental energy that I could use in the car by worrying and watching what was going on, and by the end of the race I’d be completely spent.

Celebrating a third-straight GT1 victory at Le Mans in 2006

Motorsport Images

“Now at Le Mans we have an American, Dr Andrew Heyman, who is brilliant at dealing with all that. He asked me to bring to the race pictures of the things that made me most happy. So on the wall above my bunk upstairs in the Corvette Racing hospitality unit in the paddock I stuck up pictures of my children, and the fields behind my house where I run. When I get out of the car after a stint I’ll go up and lie there and look at them while Andrew performs

acupuncture on me, particular trigger points to make you switch off: feet, hands, neck, a spot between your eyes. Within moments I’ll have switched off, and sleep deeply for two hours. Then he has a process of waking me up, a drink of the right stuff, a squirt of ginseng extract up your nose, plus other herbal extracts like rhodiola, which junior surgeons use to keep them alert on long night shifts.”

All this is a long way from Olly’s first steps in karting, aged 11. His father wanted something to do with Olly and his older brother Marcus at weekends. “By the time I was 14 I was doing the British Junior Championships at Kimbolt on, and I was on the front row with a Scottish boy called Coulthard just behind me. It was the biggest race I’d ever done, and it was pretty ferocious. DC passed me for third, went to take the second-place man, made a real mess of it and spun, and I went over the back of him. So neither of us did any good. I’ve reminded him of that a couple of times since! “Then I did the racing school at Brands Hatch, and I met Graeme Glew who ran Team Touraco. He entered me in a Formula First in a five-race winter series at Brands Hatch, on a rentadrive basis. It was a cold and wet winter, racing in rain and sleet, and standing around in the cold. I won my second race, and I could maybe have won the series, but I got excluded from one round for overtaking under a yellow — it was so dark you couldn’t see the flags.

“In 1991 I did a full season of Formula First with Fortec, still paying for the drive. We pretty much dominated the year. I won every race except one, when I was starting from pole but stalled on the line and collided with my teammate coming back up the field. I also did a Formula Renault race — qualified on pole and finished third — and some Vauxhall Lotus with— David Sears, finished second in the final race at Silverstone. Then I found out I was one of the six finalists for the McLaren Autosport award.”

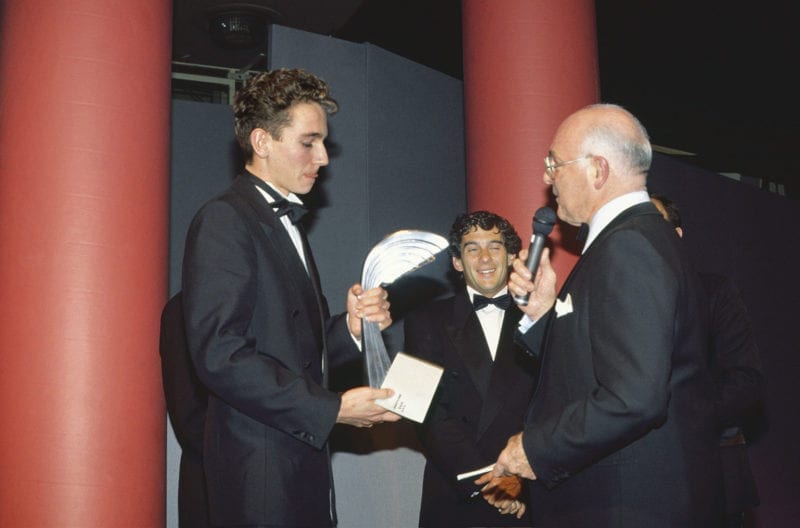

The others were Dario Franchitti, Guy Smith, Dino Morelli, Jamie Spence and Jonathan McGall. The Awards selection format called for each driver to be put into a car one formula above what he’d been driving, and because of Olly’s brief experience in FR and FVL he was put into an F3 car for the first time in his life, an Alan Docking Ralt. “It wasn’t easy getting my 6ft 2in into the cockpit with the standard seat, and I had no idea what to expect. It was very cold that day at Donington, and I got on the kerb on the way out of the first corner, needed full opposite lock to catch it. If I’d spun in the first corner, that would have been really embarrassing.” But the judges were very impressed by his times, and his results in the fitness tests. On the night at the Grosvenor House Olly’s name was called out, and Ayrton Senna presented him with his £20,000 cheque. “He said to me, ‘I hope this will be one of many,’ which is a memory I cherish. I gave all of the £20,000 to my dad, because he’d lent me the money for my racing up to then.”

Struggling to keep the safety car on track in 1999 French GP

Motorsport Images

For 1992 Olly moved on to Formula Vauxhall with John Village — “he really taught me how to set up a car” — and his first race abroad was — at Spa. He bought a video to learn the track, then put it on pole and won. Having finished second in the championship he moved on to Formula 3 with Peter Briggs at Edenbridge Racing. “We started with a Ralt chassis, which turned out not to be very good that year. After a few races Peter shrewdly realised the Dallara might be better, so we flew to Italy, brought one back, and the first race we did with it we won from pole. We won four races running, which turned the championship on its head, and made everybody else switch to Dallaras too. Once Paul Stewart Racing had got their heads around theirs, Kelvin Burt was the class of the field. I was still a bit too green to get the maximum from the car, so I finished second in the series.

“Then we felt we had to move on to Formula 3000, and that’s where things started to go wrong. Keith Wiggins’ Pacific Racing had run Coulthard in 3000 that year and done quite well. Keith told me he was starting his own F1 team, and I could be their F3000 driver and also F1 test driver. It all sounded great. But they didn’t have the money to run the F1 team, let alone keep on with F3000, and it was naive of me to think they could. In the end I scrabbled a drive with Roger Orgee and Omegaland, and we had a couple of half-decent showings, but I had a big crash at Pau, knocked myself out and broke the car in two. Then Lola wouldn’t release the car because they were owed money. In the end the whole thing unravelled. As for the Pacific F1 test role, I drove the car once, for five laps at Snetterton, and it had F1 suspension on one side and F3000 suspension on the other, because they didn’t have enough bits. That was my career as a Pacific test driver.

“The only thing to do was to go back into F3 with Pete Briggs and Edenbridge — but if I did that I would have to win the title, otherwise I’d not be taken seriously any more. It literally was win or bust. I had the same engineer I’d had in 1993, Ian Morgan, who went on to be chief engineer at Red Bull when they won the World Championship in 2010 and 2011, a fantastic man to work with. It was really between Helio Castroneves and Ralph Firman, both of whom were with Paul Stewart, and me. If Helio had crashed less often in the early part of the season he would have walked it, but it all came down to the final race at Thruxton. Ralph and I had had quite a few run-ins that year, but in that final I concentrated on keeping ahead of him, so Warren Hughes won it, Jamie Davies was second, I was third, and Helio and Ralph were sixth and seventh. Job done.

“Four weeks after that final F3 round came the last F1 race of the year, the Australian Grand Prix at Adelaide. So I’m straight on the phone to Keith Wiggins saying, We should get something for the money we’d put into Pacific F1 — because we’d got them some sponsorship from GQ and a couple of other small sponsors, and we’d put in some family money too. So he says, ‘OK, Olly, fly out to Australia, we’ll get your Superlicence organised for you.’

“I’d still only done those five laps of Snetterton in the car with the wrong suspension, but I was raring to go. I get to Australia, I’m being fitted into the car, I’ve already been interviewed by Murray Walker as Britain’s newest Fl driver. The story was supposed to be that Bertrand Gachot, who was usually the car’s driver with Andrea Montermini, had hurt himself in a jet-ski accident on holiday since the Japanese Grand Prix. Suddenly there’s Keith Wiggins looking like it’s bad news, and Gachot standing there with a smirk on his face. I was told that there was a problem with my Superlicence, and I wouldn’t be driving. So I went to see Bernie. I told him I’d come all this way, and how could it be sorted out? Bernie said, ‘Oliver, here’s the deal. You’re obviously a very good driver, but the problem is that Pacific Grand Prix are going out of business. They won’t be here next year. You haven’t tested the car properly, you haven’t driven at Adelaide before, you haven’t done a Grand Prix before. Come back to us with a good team next year and we’ll be delighted to have you.’

Receiving the 1991 Autosport Young Driver Award from Ayrton Senna

Motorsport Images

So I’d seen the man at the top, and he’d given me some time, hadn’t just fobbed me off. You could see he was very busy and he had a lot going on, but equally he was absolutely aware of the situation. He didn’t mess around, he was direct and straight to the point. I don’t know to this day whether Pacific had ever intended to put me in the car or not. I think by that time Gachot’s sponsors were pretty much keeping the team afloat. My father flew out to watch me race, and I met him at the airport and told him the bad news. He went to the track and had a not-so-quiet word with Keith Wiggins, because some of it was his money. But there was nothing we could do.”

For 1996 Oliver found work driving for Opel in International Touring Cars. “I had some good races, but more often than not I was taken out. There was plenty of contact: Hans Stuck and Klaus Ludwig were pretty smart at that. I was rather green coming into touring cars for the first time, and I was sharing the track with some very astute, politically savvy team-mates like Manuel Reuter, who won the title that year. But it was a good lesson in dealing with a large manufacturer team. Then in 1997 I tried to raise enough money to go back into Formula 3000. It was on a real shoestring: the series had gone to a one-make Lola chassis, and we needed to go testing and spend time getting it right, but we didn’t have the budget for that. It was just turn up, and perform. At Silverstone first qualifying was in the rain and I was secondfastest, but for the second session it dried out and I didn’t even qualify. At Helsinki I crashed in practice. We didn’t have the spares to fix the car, so we had to come home.

“That was when the Fl safety car opportunity arose. After the Adelaide fiasco I still hadn’t given up on Fl, and I was desperate to keep my face around. Pete Briggs told me Charlie Whiting was looking for somebody to drive the safety car, so I did a practice with Charlie at Silverstone before the 1997 British Grand Prix, and after that I was in. I had Peter Tibbetts in the right-hand seat communicating with Charlie and Herbie Blash in race control, and Professor Sid Watkins was with a driver in the medical car, with his No 2 Gary Hartstein sitting in the back with an anaesthetist and all the kit. We’d sit at the end of the pit lane for the entire race, strapped in, engine running. Then we’d hear on our radios, ‘safety car stand by’, and then ‘safety car go!’ They’d try to send us out at the front of the field, but sometimes we’d be waving cars by while we looked to pick up the leader. It was a real responsibility. At each race, whether we were at Monza, or Monaco, or Montreal, Bernie would come over to me, poke me in the stomach with his walkietalkie aerial and say, ‘No pressure, boy,’ and walk off.

F1 testing with Renault at Silverstone in 2002

Motorsport Images

“The point is, an AMG Mercedes CLK 550 is a very quick car in road car terms, but out there with the Fl cars you had to drive at ninetenths, you were really on it. Even then you’d only just be lapping quick enough for the Fl cars to keep their tyres warm. Charlie told me it was something that Ayrton Senna had brought up at a number of drivers’ meetings before his accident — how important it was for the safety car to be driven fast and well enough so they could keep heat in their brakes, and temperature and pressure in their tyres. Our AMG CLKs arrived at the track with Mercedes engineers looking after them, and it was a very serious operation.

“The toughest one was the 1999 French Grand Prix at Magny-Cours. We knew bad weather was coming. Then it went dark, and suddenly it was torrential. ‘Safety car stand by… Safety car go!’ I leave the pits onto a completely flooded track, round the long righthander, and on the back straight the wipers stop. I fumble with the switch, back and forth, and just as I get them working again, going up to the chicane there’s a massive puddle, which I haven’t seen. The car goes completely sideways, and all I can think about is what Bernie will do to me if I beach it in the gravel. The car goes one way, then the other, finally I manage to get it back, and then Herbie’s on the radio saying, ‘You’ve got to slow down, the Fl cars can’t keep up.’ The next lap, by that puddle where I’d nearly lost it, there were five Fl cars deep in the gravel. Unlike me they had no ground clearance, and they’d just water-skied off. I had to lead the field round for 11 laps until they got things sorted out.

“Driving the safety car I got to know well all the people who made a Grand Prix work — Charlie, Herbie, Jo Bauer the technical delegate, Max a little bit, Bernie every now and again. And of course Prof. Sid was so generous, he’d look after me. We’d go out to dinner, and he’d always know a couple of local characters to invite along and exchange outrageous stories. He was so down to earth, a marvellous man just happy to be living life and being around people. He treated everybody exactly the same, whether they were Bernie or Joe Bloggs.”

Keeping his face around the circus actually did get Olly some F1 seat time. When Benetton signed up a new sponsor in FedEx, they wanted to paint a car up with the new livery and show it off to the FedEx executives at Silverstone. But it was between the Japanese and Australian Grands Prix and Jean Alesi and Gerhard Berger, the Benetton drivers, and the regular test driver Alex Wurz, were on the other side of the world. “I’d just fallen off the plane back from driving the safety car in Japan and was seriously jet-lagged, so when I got the call to be at Silverstone the next day I thought it was a wind-up. But they had Alex’s seat in the car, he’s 6ft 2in just like me, and it fitted me fine. I did 10 laps for the Fedex people, and they were happy, and then Benetton said, ‘You did all right. Come back tomorrow and have a decent stint. But we can only pay you this much a day. No arguing, no negotiation.’ Well, I didn’t argue: it was far more than I’d ever been paid for a day’s work in my life.

“I ended up doing three days for them, and from then on whenever they wanted to try something, mainly aerodynamics and other bits and pieces, they’d call me. I was a sort of journeyman, trusted to give them sensible feedback and not crash it. Later on I helped develop the Renault launch control system, which they reckoned was the best on the grid. They knew that if their car started on Row 3, it’d get to the first corner beside the cars on Row 2. I had a 10-year gig, on and off, with Benetton and then Renault, from 1997 to 2006. Great experience.

Last attempt at F300 with Edenbridge in 1999

Motorsport Images

“It was about the start of 2000 that I finally had to accept that F1 wasn’t going to happen for me. I had a few drives in Formula 3000 in 1999 in a car that Pete Briggs got together, and finished fourth at Monaco. But I’d just got married, Helen was pregnant, and I had to earn a living, so I decided to look to America and sports car racing. Keith Wiggins was now sales director at Lola, so I went to see him and told him I reckoned he owed me one. He put me in touch with an American called Scott Schubot who had bought a Lola sports car chassis, and he sold me a co-drive in his car at Homestead for $10,000 cash. I took out all the savings I had, and that paid for my first GrandAm race. It was the final roll of the dice.

“I get to Homestead, and I qualify the car on pole — only to be put to the back of the grid for some technical infringement. I start from the back, we’re coming through well, and I come up behind this guy called Jack Baldwin, in a Riley & Scott. He doesn’t want to let me past so I have a wheel-banging contest with him, he gets a puncture and has to make a pitstop. I do another lap, and he’s ahead of me, waiting for me, and as I come alongside he gives me the biggest chop, spits me off the road, gives me a puncture. I manage to get the car in and hand over to Schubot. Then the team chief says to me, `Olly, you want to be careful. Jack Baldwin’s looking for you,’ and I see this huge man with enormous hands coming towards me down the pitlane. So I go and hide in the truck. When I take the car over again I have more contact with another car and lose the nose, and we end up fourth. Not a bad start.

“On the back of that I got a drive with John Field in another Lola. Now I only had to pay for my flights, and then as we got some decent results he started paying for my flights and then even paying me a bit, too. After the fourth or fifth round we’re at Three Rivers, I’m going down in the hotel lift and it stops at a floor and the doors open, and in steps a huge man with enormous hands: Jack Baldwin. He shuts the lift doors, then he’s got me by the shirt collar, pressed up against the wall. ‘You young limeys think you can come over here and mess with us good ol’ boys in America. Don’t ever do that to me again.’ Since then we’ve got on pretty well, actually.

“I carried on driving for John Field in 2001, and we started winning races. There was a great group out there — James Weaver gave me a lot of advice and help, and Andy Wallace and Butch Leitzinger. Steve Saleen got in touch, and I did the Sebring 12 Hours for him with Franz Konrad and Terry Borcheller. I put it on class pole, but up to then no Saleen had ever run for more than three hours. We had a few dramas, but so did the Corvettes, and amazingly we won the thing. When I came in to hand over for the last time, looking forward to getting out, I see Franz and Terry standing there with no gear on, and they stuff me back in the car and send me out again to the finish. It was the first proper endurance race I’d ever done, and in those days I had no idea how to prepare myself for it. By the end I was completely finished. But that win really helped my standing in America.

Chasing Kelvin Burt for the 1993 Formula 3 title

Motorsport Images

“I continued with John Field for the rest of the season [he got three wins and five podiums], and I did my first Le Mans with Saleen. That year I think it rained for 14 hours. Going down the Mulsanne Straight the rain was coming in around the doors and pouring down onto my lap. Then it would get on the electrics and the thing would misfire, and the screen would be all misted up. But we kept on. After 20 hours we holed a piston, but Terry got the car going at the end and we chugged over the line for third in class. That autumn Doug Fehan met me in the paddock at Laguna Seca and offered me a seat at Corvette Racing. After 11 seasons, I’m still there.”

At first it was just a drive in the long-distance races: Le Mans, Sebring and Petit Le Mans. Oliver won his class in all three, and thereafter he was a full member of the team. At Le Mans in 2003 he was second after a long delay for gearbox repairs, but he won the next three years on the trot. “From 2004 until 2010 my team-mate was Olivier Beretta, and we were joined in the longer races by Jan Magnussen. We were three different characters who generally drove the car the same way and wanted the same things. Qualifying is always good to watch when Jan is in the car: he can roll his sleeves up and produce a lap time apparently from nowhere. It was always fun to drive with him. For 2012 he was in the other car, but we still talk and swap information, because that’s what you do in endurance racing. It’s a team effort. Olivier is a very aggressive driver, he always drove by the seat of his pants, arriving at a corner elbows out, really hard on the brakes. But when the team changed from the GT1 car to the GT2 car, with no carbon brakes and less downforce, Olivier was less happy, and he left during 2010. It was the team’s decision to switch from GT1 to GT2. In GT1 there wasn’t really anybody left for Corvette to race, and in GT2 we’ve been up against Porsche, Ferrari, Aston Martin, BMW and Viper, so the racing is much more meaningful.

Saleen drive in 2001 led directly to Corvette deal

Motorsport Images

“Having been part of Corvette for so long now, I have a huge passion for it, and I’ve tuned my driving style to suit it. It brakes exceptionally well because of the front engine and the front tyre we’re using, and it puts the power down well, gets hooked up out of corners. But you have to remember it’s just a great big frontengined push-rod V8 musclecar. When I first started driving it in 2002 I was taken aback by how loud the car was — not just the actual noise, but the vibration, which goes through your body and shakes you physically. The heat inside was pretty bad, but they now have an air-conditioning system which does drain a bit of power but circulates cool air not only on your face but also through the seat back. In 2012 I only really felt the effects of the heat at Mid-Ohio and Baltimore, and both of those were pretty humid races.

“The cars are built by Gary Pratt and Jim Miller, who as Pratt & Miller run Corvette Racing from a base in New Hudson, 40 minutes out of Detroit. They’ve developed the Corvette for 16 seasons now, and they’ve done Le Mans 12 times. That’s a long time for a factorysupported programme. At the American races there’s huge support from Corvette owners, with a Corvette Corral for them to park in and watch from, and we always have the longest autograph line. All credit to General Motors for having stuck with it through all the recent recessionary problems. In 2008, when the US Government bailed-out GM, they had 15 competition programmes running. They axed the lot except support for three NASCAR teams, and Corvette Racing. Le Mans remains hugely important to them. Last time we won there the president of GM North America, Mark Reuss, was standing with us on the top step of the podium, and he was just thrilled to be there.

“For my last race of 2012, Petit Le Mans at Road Atlanta, I decided that instead of flying down from Detroit I’d go in the truck with the boys, just to see what it was like. It was 800 miles, and we did it in 14 hours. About three hours in I was thinking, where’s the nearest airport? But I stuck it out, and it gave me a good perspective on another part of the whole team effort. When they get there they have to get the truck washed and looking presentable before they can even get into the paddock, start unloading, and then start on the race cars. As is always the case in a team, you can’t do your job without them doing theirs. That’s what I love about sports car racing. The team is small by F1 standards: about 35 people go to each race, drivers, engineers, mechanics, support crew. The whole gang works together, eats together, plots together: set-up, strategy, pitstops, the lot.

“Pitstops are practised endlessly. In a 24hour race you have more than 30, so saving fractions in the process, releasing the car just right, can make a big difference. For tyre-changing the ALMS rules allow two guys and one wheel gun per side, and they can change four tyres in about 7.8 seconds. While it’s refuelled you can clean the screen and change the driver, but you can’t do anything else.

“There’s something magical about Le Mans. On Saturday morning during the build-up the atmosphere is electric. Since 2003 I’ve always taken the start, and on the first lap, going down the Mulsanne Straight to the first chicane, it can get pretty crowded. Then you fall into a routine. The real work comes during the night and on into the morning, that’s usually when the race is won or lost. The last four years it’s gone wrong for me on Sunday morning: a lost wheel, a gearbox problem, a crash. In 2010 Jan was put on the grass by a slower car, and it was quite a big accident. And it’s flat out the whole time, just qualifying laps, qualifying laps, never any letup. It’s all down to being properly prepared, properly focused.”

Oliver Gavin is clearly stimulated and fulfilled by his hectic transatlantic sports car career: five drivers’ championships and 41 victories in Corvettes, and counting. “I’m now the longest-serving driver in the team. I have another year of my multiyear contract to run, and naturally I hope it’ll be renewed for 2014. But you can never feel complacent, because everything hangs on your performance. This is a results business.

“Of course I would have loved to have made it in Grand Prix racing. Racing against people who have been in F1, I’ve felt equal to many of them and quicker than some. But I consider myself very fortunate to have been able to earn my living driving racing cars, and it’s made me determined to go on doing so for as long as I can: keep up my fitness, my professionalism, my competitive speed. And you never stop learning. The day you think you know it all is the day you start going slower.”