Lunch with Mike Costin

At one time Colin Chapman’s deputy, Costin is famed for his engine business with Keith Duckworth. And when it came to product testing, he was handy at the wheel

The first seeds of many a great enterprise have been planted by the meeting of two young people with similar ambitions and complementary talents: like the day in May 1904 when Charles Rolls and Henry Royce sat down to lunch in a Manchester hotel. Over a century later, the combination of their names remains a household word. When Mike Costin (27) and Keith Duckworth (23) bumped into one another in the hectic little Lotus works behind a North London pub in 1956, they could hardly have dreamed that the combination of their names – the first syllable of one and the second of the other – would be cast on the cam-covers of the most successful racing engines in history.

Mike might have spent his life in the aeronautical industry. The youngest of four children, he was passionate about aeroplanes from an early age, and left school at 15 to take up a five-year trade apprenticeship at the De Havilland Aircraft Company. His eldest brother Frank, nine years older, was already working in aviation, helping to sort out the aerodynamic quirks of the twin-boom Vampire jet fighter. Mike was no academic at school, but after two years De Havillands appreciated his practical intelligence and upgraded him to engineering apprentice. “That made a vast difference. At the end of my apprenticeship I did my National Service in the RAF, and then went back to De Havillands designing test rigs for, among other things, the Comet airliner.

“A De Havilland student apprentice, Peter Ross, had a friend called Adam Currie who was into motor racing. I went with them to some 750 Motor Club pub meetings – they called them noggin-and-natters – and one of the people I met was Colin Chapman. He was winning everything in 750 Formula events with the Lotus Mk3, and was building the Mk3B for Adam. One night Colin wanted to borrow an Ulster camshaft and another of the gang, Derek Wootton, had one at home in his shed. He had this 1928 Chummy with a Ford 10 engine. They set off in the dark with Wooty driving flat out and Colin, in the Mk3, struggling to keep up. The Chummy had no headlights and windscreen, and it wasn’t until they got there that Colin realised Wooty was wearing a pair of sunglasses to stop his eyes watering. In the dark, with no lights…”

The 49’s rollout at the Lotus factory with (L-R) designer Maurice Phillippe, Keith Duckworth, Graham Hill, Mike Costin and Colin Chapman

Motorsport Images

Chapman was quick to see the potential in Costin. He’d set up Lotus as a going concern at the start of 1952 with the Allen brothers, Nigel and Michael, but in January ’53 Colin began a new arrangement with Mike. “After his bust-up with the Allens I was his only member of staff. At first there’d be nobody there during the day, because Colin still had his job at British Aluminium, and I was at De Havillands. I’d do a full day’s work there, eight till six, then drive my Austin 7 from Hatfield to Hornsey, get there for 7.30pm, work through till around 2am building up Lotus Mk6 kits, and then drive home for four hours’ sleep. Then back to De Havillands with various bits that needed heat-treating and stuff like that, and my pockets full of cigarettes to bribe my work-mates to do it.

“After we’d built the first batch of eight Mk6s, Colin decided we’d pulled in enough funds to build one for ourselves to race. I did everything on that car. I linered the engine down from 1172cc to 1098cc, so I’d drive it in 1172 Formula races and Colin could race it the same day in 1100cc sports car events. For 1172 racing you weren’t allowed to change the camshaft, so Colin thought, ‘Why not reshape the tappets, so they open the valves earlier and keep them open for longer?’ I designed the tooling to do this and made it all up, and the car was very quick.

“In 1954 Colin wanted to progress from cycle wings to an all-enveloping shape. He had some ideas of his own, and came up with a balsa-wood buck which looked sort of like a C-type Jaguar. I didn’t think much of it, so I showed it to Frank. Frank said, ‘What are you mucking around with cars for? We’re aircraft people.’ But I persuaded him to tell us what to do. He covered Colin’s balsa buck with plasticine, giving it a low wide front and long fin-shaped rear wings. Colin took one look at it and said, ‘That’s no good at all. Far too long, far too wide, far too much frontal area.’ Frank said, ‘You want aerodynamics, you’ve got them there.’ So Colin went along with it, and that was the Mk8.

“Of course it worked brilliantly, and Frank had input into all the Lotus shapes for a long time after that. Later on Derek Wootton ended up working for Vanwall. He suggested to Tony Vandervell that Colin should be consulted on the chassis of the new Formula 1 car, and Frank should come up with the aerodynamics. That Vanwall won nine Grands Prix and the first Constructors’ Championship. Frank went on to be the Cos in Marcos, and then did his own cars like the Costin-Nathan and Costin Amigo, all using the wooden monocoque construction that he was so fond of. He was a total enthusiast and a wonderful character, but he was no businessman. He’d tell me about his latest project, all excited, and I’d say, ‘Frank, is the money all right?’ And he’d say, ‘This time it’s fine, it’s all tied up.’ But it usually wasn’t. He got taken for a ride over and over again.”

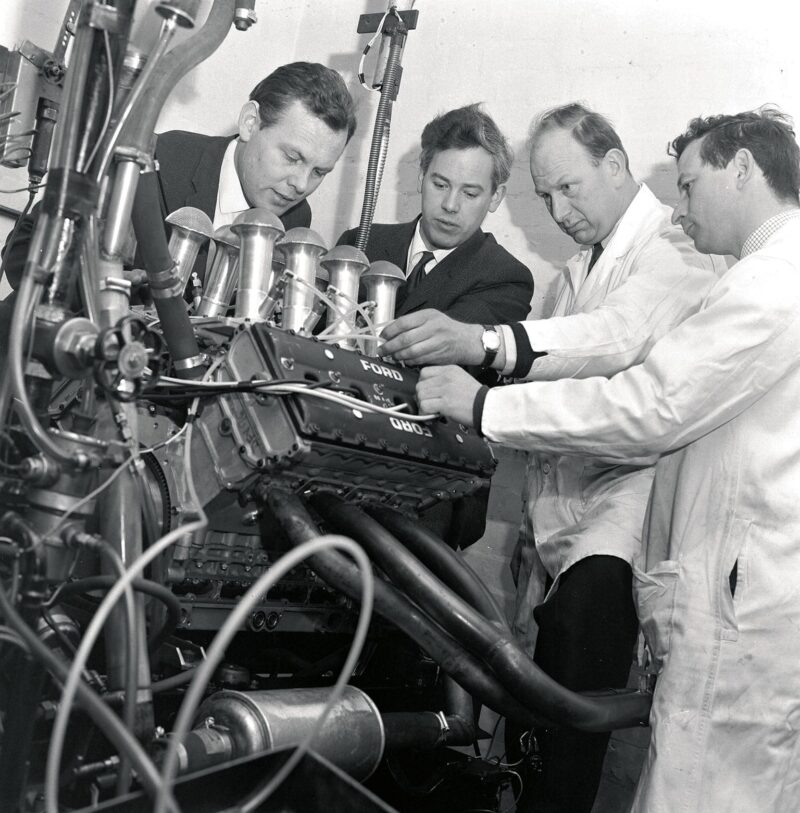

From left: Bill Brown, Keith Duckworth, Costin and Ben Rood pose with the first DFV on the test bed in 1967

Ford

In January 1955 Mike bowed to the inevitable, left De Havillands and started at Hornsey full-time, on a salary of £15 a week. “By then Lotus had grown to about 15 people, with Nobby Clark managing production. I effectively became Colin’s number two. And in 1957 this college leaver turned up, called Keith Duckworth. He was hired by Colin as development engineer on the Lotus sequential gearbox, the infamous ‘queerbox’. Keith had already been a Lotus owner: he’d built up a Mk6 kit with a Climax engine, and raced it three times before deciding that he wasn’t a racing driver. We actually came across each other first when he did some vacation work at Hornsey during the summer of ’56.”

*

Keith’s full-time employment at Lotus didn’t last long. “He became frustrated with the queerbox, which he thought was fundamentally flawed. But he sorted out the oil circulation, and he designed the positive-stop change mechanism. That really impressed me: he did the drawings, made the bits, assembled it, and it worked straight off, didn’t have to be modified at all. Actually, the queerbox would have worked if it had been made an inch and a half longer, so each individual gear could have been a quarter of an inch bigger, and the shaft and its dogs would have been able to work in the middle of the dog instead of putting all the forces on the end. But Colin wouldn’t have it. He always wanted everything to be as compact and light as possible.” It may have been as early as this that Duckworth came up with one of his famed aphorisms: “Development is only necessary to rectify the ignorance of designers.”

Meanwhile Lotus had moved to Cheshunt and was going from strength to strength, its sports-racers running through the 11, 15 and 17 while its single-seaters were the 12 and the 16. “Nobby and his team were building the production cars, while I was developing the prototypes. And there were always modifications to do, like when a customer wanted to use a different engine which wouldn’t fit. I’d have to look at it, decide which tubes to move, do a quick sketch for some different brackets. I wasn’t doing much racing of my own now, I was working too hard.” But he had a rare outing at the 1958 Boxing Day Brands Hatch meeting, when Lotus took three pre-production Elites for Jim Clark, Colin Chapman and Mike.

“The three of us were on the front row, and when the flag fell and we were hammering three abreast down into Paddock Bend I knew I’d be the first to lift. Colin was super-competitive and very brave, he could really hang it out. He and Jimmy had a wonderful battle, which Colin won. I was third, a respectful 6sec behind.

Mike tested Cosworth’s abortive 4WD car at Silverstone in 1969

Motorsport Images

“Keith and I got on well from the start. His personality was completely different from mine, but we struck up a real friendship. By the end of each racing season I would be fairly well knackered, and I was always thinking of moving on somewhere and having a better life. At Lotus it seemed there was never time to do it right first time, but then we always had to find time to do it again. Keith couldn’t really get on with Colin, because Colin always wanted a quick answer to every problem, and Keith refused to give him a quick answer because he liked to think everything through logically. That was really what gave rise to Cosworth.

“Keith and I talked about it a lot and decided to set up a small engineering company doing motor racing work. Cosworth Engineering Ltd was incorporated on September 30 1958. But to start with it had to be just Keith on his own. The thing was, he was unmarried: I had a wife and three kids by now, and I needed a steady salary. So when my contract with Lotus came up for renewal I signed on the dotted line for three more years. I was able to help Keith peripherally, but at Lotus we were getting the Elite into production, which was a real headache.”

After humble beginnings in a corner of a shared mews garage in Kensington, Duckworth moved to a dilapidated stable in Friern Barnet. He spent his £600 savings on a dynamometer which was bolted to the floor, with the exhaust pipe going through the roof. At first most of the work was preparing existing cars for racing customers, but a big turning point came when Lotus announced its Formula Junior single-seater, the 18. FJ was taking off in a big way, and the rules required use of a pushrod production engine. In Europe Fiat engines were popular, while in the UK most felt the BMC A-series was the natural choice.

Chapparal 2K Indycar (5) used turbocharged DFX for Johnny Rutherford to win the 1980 USAC title

Motorsport Images

“Graham Hill, who had worked for Lotus for several years and been a works driver for us, was also a director of Speedwell, which specialised in tuning the BMC engine. He pushed Colin hard to use it in the Lotus 18, but I knew the A-series, with its small bore/long stroke architecture, was near the end of its development. Keith heard that the new Ford Anglia 105E, which was about to be launched, would have an over-square engine, capable of much higher revs.” Thanks to Mike’s persuasion, Chapman decided to use a Cosworth-tuned 105E unit for the Lotus 18.

“Initially Lotus laid down 25 FJ chassis. But with Jim Clark winning everywhere, the Cosworth-powered 18 quickly proved to be the chassis and engine to have. By October we’d made 125 cars. We bought 105E engines in batches of 10 and shipped them down to Friern Barnet. The Cosworth 105E went through Mk2, Mk3 and Mk4 variants, getting different crank, rods and pistons and a better cam profile along the way, and in the end we were getting 100bhp per litre from a production block pushrod engine. It’s all about revs: as long as you can keep your volumetric efficiency, more revs means more power.” Only a few years earlier, 100bhp per litre had been enough to win in F1.

In August 1962 Mike’s contract with Lotus expired, and he was free to join Cosworth full-time. “Colin understood, but a lot of people couldn’t work out why I was leaving a nice secure job as technical director of Lotus for this tin-pot operation up the road. Cosworth had outgrown Friern Barnet and moved to a scruffy old building in Kenninghall Road, Edmonton, where Lotus had assembled the first Elites. By the time I arrived there were already 16 people there – in premises about 60ft by 30ft! – with Bill Brown as general manager. We had five engine builders, a little area where we had a test rig, lathe and milling machine, and a dyno shop with three dynamometers. Keith and I had a little office up in the roof, right over where they did all the brazing and bronze welding. What with the fumes coming up through the floor and Keith’s chain-smoking, it’s a wonder I’m alive today.”

Deliveries of the Ford Sierra RS Cosworth began in July 1986

Keith Duckworth used to say that, in their working relationship, he was the idealist and Mike was the realist. “Maybe that’s right. Keith wasn’t one for mad ideas, his feet were always firmly on the ground, and he never wanted to do anything that was too dreadfully Chapman-ish. But if he dreamed up anything that was what you might call outside the box, he’d always ask me what I thought about it. Another key member was Ben Rood. To start with Ben had his own machine shop in Walthamstow, and Keith was giving him more and more work until he was our prime supplier of machined parts. In the end he closed his shop and joined us full-time. Ben had a brilliant brain, and he was a totally different character. The three of us got on well together, we did a lot of laughing.”

For his new road-going sports car, the Elan, Chapman had got Harry Mundy to design a twin-cam head for the five-bearing 1600cc Ford engine, and in 1963 it was adopted by Ford for a high-performance version of the Cortina. Lotus was contracted by Ford to race a works team of Lotus-Cortinas, and Chapman needed Cosworth to develop the engine into a reliable racing unit. “Not long after I’d left Lotus, I was back in Colin’s office with Keith working out what we could do with the Twin Cam. In the end we had to re-engineer the whole thing, different porting, different cam profiles, rethinking the oil system.” A former Fleet Street editor called Walter Hayes had been hired as Ford’s director of public affairs, and he was the driving force behind its new performance image. He helped forge strong links between the giant manufacturer and the little workshop in Edmonton.

In 1964 Formula Junior was replaced by the new 1-litre F2 and F3, the latter restricted to one carburettor. For F3 Cosworth developed the Ford 105E into the hugely successful MAE – with typically dispassionate logic, the letters stand for Modified Anglia Engine. Ultimately it would produce the magic 100bhp per litre on a single-choke carb, revving to 10,000rpm. For F2 Cosworth produced its first overhead-cam engine, the SCA (Single Cam type A). “That was a big jump, because up to then we hadn’t designed a cylinder head. Using one camshaft, the problem was to get the ideal combustion chamber shape. Keith went for a Heron head design, a flat head with the chamber formed by a bowl in the top of the piston, the idea being that you’re not shrouding the valves. It was a good system in principle, but when we got into it we found it was diabolical. We were machining different shapes into the tops of pistons every week. When Harry Mundy and Wally Hassan were working on Heron heads for the Jaguar V12, I offered to show them the work we’d done because we knew it wasn’t the way to go. But they didn’t want to listen.

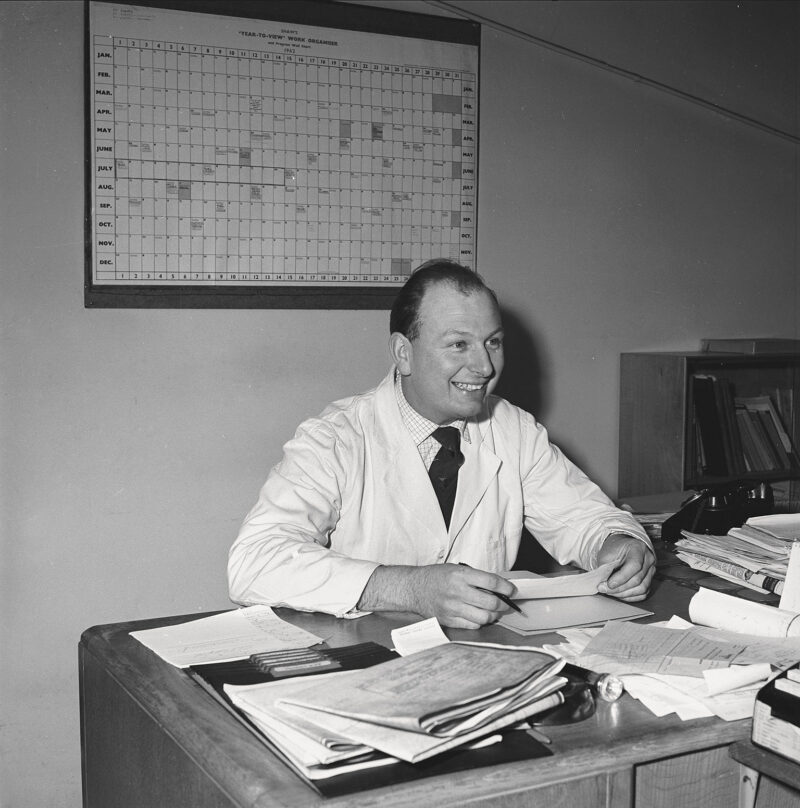

Mike at his desk in trademark white coat

Motorsport Images

“But the SCA still won every F2 race in 1964. In ’65 BRM did a little twin-cam F2 motor – effectively half their F1 four-cam V8 – but we beat that too, every time except once. Then for ’66 Honda came up with their little twin-cam with four valves per cylinder, which Jack Brabham got for his works F2 cars, and thatwas pretty well unbeatable. That got us thinking about four valves per cylinder.”

At the end of 1964 Cosworth had been forced to move out of its cramped premises in Edmonton to a new greenfield site in Northampton. “We chose it because most of our customers were in the south, and most of our suppliers were in the Midlands. Only 14 of us made the move: Keith, me, Ben and Bill Brown, and 10 blokes.” The first factory there was 7500 sq ft; but, prudently, a lot of extra land was purchased. Within seven years Cosworth would be occupying 45,000 sq ft in and around St James Mill Road.

Meanwhile at the upper levels of motor racing, things were changing dramatically. For 1966 the old 1500cc F1 was to be superseded by what the promoters were calling ‘The Return of Power’: 3-litre engines. This would be supported by a 1600cc F2. And in February ’65 Coventry Climax, which provided engines for most British F1 teams, announced it was quitting racing altogether. Cosworth was already working on a four-valve F2 engine (the FVA – Four Valve type A) when Chapman, anxious to know where his next F1 horses were coming from, approached Keith. Keith reckoned the work he’d done on the FVA could easily double up into a 90-degree V8. Plucking a figure from the air, he told Chapman he could probably design, develop and build a batch of five F1 engines for £100,000. Chapman undertook to find the money.

He tried the British motor industry via the SMM&T, and also his petrol sponsors Esso, all ithout success. David Brown, owner of Aston Martin, was interested, but only if he could buy Cosworth. Then Walter Hayes got involved. The engine could be badged as a Ford, and if it won races that would generate the right image for the blue oval. Very quickly, Hayes got board approval for the investment, and the DFV – Double Four Valve – was given the go-ahead.

“In Ford terms, £100,000 was an astonishingly small sum of money – about a tenth of what it cost Ford to give the Cortina synchromesh on bottom gear. Actually it was really £75,000, because £25,000 went on the FVA. The FVA was pretty good straight out of the box.” Producing around 140bhp per litre from the start, it ompletely dominated F2 for five years, and was also successful in other applications. “We made a 1500cc version, the FVB, to test the bore and stroke of the DFV. We put it in a Brabham F2 chassis and I did several races, just to check it out. I had some wins and broke lap records at Brands and Club Silverstone, and I wasn’t going barmy, just doing some engine testing.” At the time I wondered why one of the bosses of Cosworth would suddenly pop up in a club race in an anonymous-looking Brabham. I also noted that this friendly, practical engineer was, in his quiet way, a very competent racing driver.

Mike race-tested Lotus 20 Formula Junior with Cosworth-tuned 105E unit

Motorsport Images

Keith started work on the DFV in early 1966. “He used to work a lot from home when he was designing, and he got stuck over where to put the cylinder head bolts. He’d got three entirely different schemes on the go, three combinations of cylinder head, combustion chamber, cams and oilways, and I had to go and give him a bit of a kick to make up his mind, because time was marching on. The big thing was how the bores should be spaced. The outer bores were differently spaced from the inner bores, and the whole thing was 0.7in offset for the crank and rods. It was a four-throw flat crank, with two conrods sharing each throw.”

A revolutionary feature of the DFV’s first home, the Lotus 49, was that the monocoque ended immediately behind the driver. The engine was hung on the back and itself carried the rear suspension. “It was Keith’s idea that the engine should be a structural member, not Colin’s. It was held onto the monocoque by two bolts at the bottom and two at the top. It wasn’t that big a deal, structurally. The torsional loads going through the engine in heavy cornering were only about 4000lbs. Our big-end bolts were much smaller, and stood a load of 10,500lbs in each one.”

The first DFV was delivered in April 1967, and the first man to drive it was Mike. “Dick decided to take it to Snetterton the next day. We had a few bits and pieces back at Cosworth we wanted to try, so Colin said, ‘Take my Cherokee 260 and fly back in the morning.’ I’d never flown a 260 before, so I did a quick circuit with Colin to try it out, and then Keith and I flew back to Northampton. Next day we were flying to Snetterton. It was a perfect gin-clear morning, and I said to Keith, ‘What’s that ahead of us? It’s going very slowly. Is it a glider?’ We went past this thing at about 2500 feet, and it was a Harrier Jump-Jet, just sitting there parked in mid-air. Except not many people knew about the Harrier then, so we didn’t know what it was.

“The 49 was good sport to drive at Snetterton We worked out I was pulling 175mph on the Norwich Straight past the filling station. The engine seemed pretty strong, although the pickup after a gearchange wasn’t very good. It stayed like that for a long time. Dare I say it, it was Jack Brabham who solved that. The fuel injection system had a little cam which we’d designed by doing various tests at different throttle openings and optimising the stroke. We reckoned it would go weak going into a corner, so about where you blip we richened it up a bit. Whenever an engine came for in a rebuild that cam was taken out, put into a jig and checked. Two years later, the guy rebuilding one of Brabham’s DFVs came to me and said, ‘The fuel cam is different.’ We checked it, and it was virtually the same as our original before we’d made the change, and worked far better. So we went back to that. We didn’t tell Jack we’d discovered his tweak – he’d probably have wanted paying!”

Mike’s prime role at Cosworth was to translate Keith’s designs into production reality

The DFV made its debut at the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort on June 4, 1967. Graham Hill put his 49 on pole while Jim Clark was delayed in qualifying with a wheel-bearing problem. Hill led from the start, but retired when a cog in the cam drive broke up. Clark, from eighth on the grid, came through to score a historic win first time out for car and engine. For the rest of the season the 49 started every Grand Prix from pole. But Hill’s Zandvoort retirement had pointed to a serious problem.

“There was a torsional vibration, so we were breaking timing gears. In tests we discovered that the loads were fantastic – the peak load on those cog wheels was more than the mean load coming out of the flywheel. That was the force we had to absorb. It would have been easy to deal with if there’d been lots of space, but there was none. So Keith came up with his famous quill hub. Where the second compound gears were, we built into the hub 12 tiny shafts, six driving one way and six the other, so they could twist and absorb the forces. That did the trick.”

The DFV quickly became far and away the most successful F1 engine of all time. In the next 15 seasons it clocked up over 150 GP victories, 12 World Championships and 10 constructors’ championships. When Keith retired his leaving present from the company was a polished example of his multi-quill timing gear, mounted on a wooden plinth, with the inscription: ‘With these quills, you wrote a new book in the history of motor racing.’

*

It quickly became clear that the DFV was going to be almost unbeatable. Chapman, of course, wanted exclusive rights to the engine for Lotus. As Mike remembers, “Keith said, ‘No bloody way!’” Walter Hayes strongly agreed: if only Lotus had the engine, F1 would have become very boring with Clark and Hill winning every race. Soon every British team except BRM was using the DFV. “That first year we initially did seven engines, but once the thing took off we were making 25 or more a year, and they were always sold before we could make them. The two things that made F1 grow as it did in the 1970s were the Cosworth engine and the Hewland gearbox. Teams could make chassis, suspension, wheels, all the rest, but they couldn’t make an engine or gearbox. With those two components everybody could build their own F1 car.”

Which is what Cosworth decided to do. In those pre-wings, pre-ground-effects days, as horsepower levels went up four-wheel drive began to look more attractive. At the start of 1968 Cosworth lured young Robin Herd away from McLaren to design a four-wheel-drive F1 car. But with other priorities at Cosworth the complex machine, with three differentials and curiously angular lines, wasn’t ready for testing until early ’69. Once again Mike did the testing. “The torque-split in the middle of the car was designed by Keith and made by Ben Rood, and it was a masterpiece. Keith also designed the hubs, stub axles and wheels, which were held on by a single nut. When Robin moved to March he used exactly the same wheel arrangement. If you wanted to wind up Keith, you’d say, ‘Bloody nice wheel on that March. Didn’t Robin do a good job?’

“But the four-wheel-drive car didn’t work. The only people who drove it were me and Trevor Taylor. Trevor was a lovely lad, and a very good driver, and the idea was he’d make its debut at the British GP in July. But the car was useless. It didn’t handle, and you could only do about three laps before your arms fell off. The steering was incredibly heavy, and the feedback was dreadful. The first thing we’d have to do was design power steering for it. It needed special tyres, which Dunlop weren’t able or willing to come up with, and about 50 other things. It would have been a major project, and we were very busy then with DFV development. And of course the arrival of wings made it much less attractive. So it never raced.”

Chapman in Frank Costin-styled Lotus 8

Motorsport Images

Over time the DFV appeared in many versions. The DFL was a long-stroke variant for endurance racing, and twice won Le Mans. The DFX was the hugely successful turbocharged Indianapolis engine. By 1988 the DFV line had reached the DFR, an updated 3.5-litre unit. And in ’89 came the HB, an all-new, more compact 75-degree V8 which showed clear ancestry back to the original DFV but shared no common parts, and won races for Benetton and McLaren. With its successor, the Zetec-R V8, Michael Schumacher and Benetton achieved another drivers’ World Championship for Cosworth in 1994 – 27 years after the first DFV.

Other projects ranged from the BDA (belt-drive) family of Ford-based four-cylinders to the GA four-cam V6 using the Granada block. Although Keith publicly stated his dislike of turbocharging in a controlled racing formula, in 1985 Cosworth produced its twin-turbo GB F1 engine for the Beatrice Haas-Lola team. Perhaps for reasons more political than technological, that was never a winning project. There was also now a huge amount of contract work on high-performance road cars for Mercedes-Benz, General Motors and, of course, Ford.

“The 16-valve turbocharged Sierra Cosworth was something that Keith took on with a quick, ‘Yes, we’ll have a go at that.’ Then one morning he came into my office and said, ‘We’re in the shit with this Sierra project.’ Building the prototype, getting the power, then going through all the approvals with Ford was going to be a massive task, especially as we were in the middle of Mercedes and Opel contracts too. Keith said, ‘We’ll split the company down the middle. You be chief engineer, road engines. I’ll be chief engineer, race engines. You’ll have to go off and do it somewhere else.’ I moved into another building over the road with Mike Hall, the ex-BRM guy who’d been with us since the start of the DFV, as my chief designer. We started again. Then we built a new factory in Wellingborough for production.

“The initial Sierra contract was for 5000 engines a year. Plus there were much more powerful rally specials with a bigger turbo. Later on the boy racers could buy third-hand Sierras for very little money, chip them and get massive horsepower. Some claimed 550bhp or more. But the truth is we had to get 250bhp out of that engine in all types of everyday usage, utterly reliably. The book of tests we had to comply with for Ford was several inches thick. One was we’d take a new engine off the line, we were allowed 15 seconds to get the oil pressure up, then we had to run it at 7000rpm from cold, like somebody abusing a cold car on a winter’s morning. Then take the hot water out, put cold water in, do it again. Then take it to bits and there wasn’t to be any scuffing, anywhere. Then there was the 300-hour test: 24 cycles of 12.5 hours each, maximum power for a set period, then drop to maximum torque, then to tickover, then to maximum power again. For 300 hours. Then strip the engine, and all wear had to be within strict limits. Then reassemble the engine, you’re only allowed to change gaskets and O-rings, and the same cycle for another 300 hours. It was all in the Ford contract, but I don’t think Keith read the small print when he signed…

“We also got involved with boats. There was a DFV-powered craft that set some water speed records, and an open-class boat in America with two turbocharged DFXs, running nitrous-oxide injection. It won a big race, but they wouldn’t give it the prize because they said it didn’t comply with the rules, even though it had passed scrutineering. Ben and I reckoned we should do a light aircraft motor, but Keith never wanted to do that. But there was a 750cc twin motorcycle engine that we did for Norton-Villiers-Triumph, like a two-cylinder vertical DFV. We made some prototypes in the 1970s, then NVT had all their problems, and they gathered dust on a shelf. In 1984 Keith gave two engines to Bob Graves, who developed it with some help from Cosworth and ex-Cosworth guys. He built a special bike for it, and Roger Marshall rode it to win the 1988 Daytona Battle of the Twins.”

*

When Cosworth was founded in 1958 Keith and Mike wanted to create a small specialist company, a tight organisation that was the best at what it did. Despite their best intentions, it grew into a substantial group, eventually employing over 800 people in two continents. In 1980 Cosworth was sold to United Engineering Industries and Keith distanced himself from day-to-day management, retiring completely in 1988. A long-time victim of heart trouble – he’d had his first heart attack at 40 – he died in 2005, aged only 72.

Mike succeeded Keith as chairman of Cosworth, before retiring himself in 1990. Through a complex sequence of public company deals, by 1998 Cosworth had ended up in the hands of Volkswagen. VW sold the racing division to Ford, and passed the rest over to Audi. In 2005 that was bought by Mahle and is now called Mahle Powertrain UK, but it’s still based in Costin House, St James Mill Road, Northampton. When Ford called time on its F1 programme in 2004 and sold Jaguar Racing to Red Bull, US motor sport tycoons Kevin Kalkhoven and Gerald Forsythe bought Cosworth Racing. As well as motor sport, including F1 and Indycar, it’s also active in energy generation, aerospace and defence. It operates from Northampton and Cambridge, and three locations in the USA.

Even though Mike’s career switched from wings to wheels, aircraft never stopped playing a role in his life. At 82 he is still a hands-on glider pilot, doing competitions up and down the country. “At Lotus Colin always had aeroplanes – even in my day he had a Miles Messenger which I used to fly a lot. At Cosworth we always had a company plane, even if in the beginning it was an old Auster. I still have shares in two, a Europa and a Robin Regent. But gliding takes up a lot of my time.”

So Cosworth, now, is a huge multinational enterprise stretching from Torrance, California to Maharashtra, India. But it would never have been born had not two young men coincided in the little Lotus works over 50 years ago. The chemistry could not have been better: the brilliantly inventive, determined idealist who always thought things through to find the best solution; and the hugely talented yet always down-to-earth engineer who just liked making things happen.